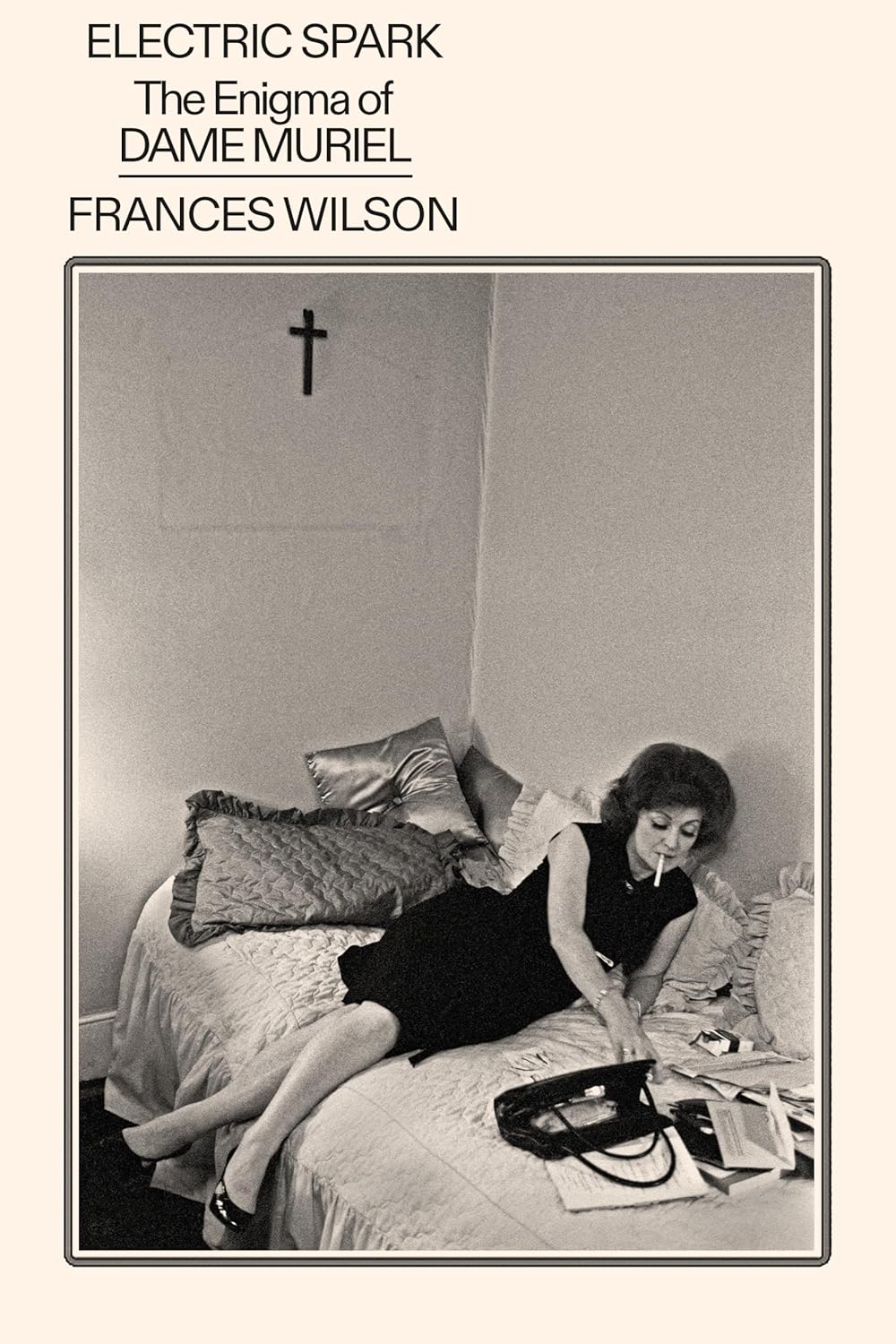

THE UNCANNY fertility and invention displayed by the writing of Muriel Spark has been a consistent source of awed bemusement. Gabriel Josipovici, an experimental writer quick to identify Spark as a rare British predecessor, called her novels—she published twenty-two in all—“a joy to read and a nightmare to talk about.” Renata Adler, in the Spark chapter of the 1964 anthology On Contemporary Literature, called her “unfathomable.” Acquaintances and scholars couldn’t understand how Spark could write by hand with such fluency, barely blotting a line in the seventy-two-page exercise books she bought from the Edinburgh stationer James Thin. “How she gathered the fascinating material on seances in modern London,” John Updike wrote, in the first of ten reviews of her work, “I can’t imagine.” Responding to the same novel, The Bachelors (1960), Evelyn Waugh asked simply, “How do you do it? I am dazzled.” Now Frances Wilson, the ingenious biographer of Dorothy Wordsworth, Thomas de Quincey, and D. H. Lawrence, has given her book about Spark’s early life the subtitle The Enigma of Dame Muriel, and makes much of the coincidences she experienced as well as her supposed ability to foretell her own future: “There was something spooky about her.”

Yet despite—or alongside—this reflexive response, Spark’s career has proved unusually yielding to exploration. In Spark’s own statements about her work, in her fiction about writers and artists, and in her writing as a critic, she was immune to the allure of reverent or superstitious silence. In 1950, when she was embarking on a study of the UK poet laureate John Masefield, she wrote him that questions like “how the creative mind gets into focus” are “no doubt unanswerable”: “Still, one must try to answer them.” A little over a decade later, when her work had become, as she put it in a promotional biographical note, “famous throughout the world,” she told Allen Tate—a former US poet laureate—that she found it “quite easy” to answer questionsabout how she wrote. Though Wilson quotes six occasions on which Spark called herself a “magnet” for the experiences she needed for whatever novel or story she was writing, what she was referring to was not mediumship or time-bending but creativity. Spark believed that she had access to knowledge that she couldn’t possibly have gained through “normal channels.” Well, she certainly wasn’t normal, but not because she was, as some reckoned, a “witch.” Invoking magnetism on a seventh occasion, she noted that it was a gift shared by “all artists.” And as Wilson’s book, after its initial occultist gestures, nimbly and exhilaratingly shows, Spark was a true artist, a natural, set apart from the common run, capable, as the narrator of “The Portobello Road” says, of drawing unusual connections, divining hidden patterns and processes, and making expedient or ruthless use of everything she saw and did.

Still, she took a lengthy run-up. One of the reasons why Wilson can offer a complete portrait despite her limited scope is that most of the significant events of Spark’s life, and the basis for most of her fiction, had taken place by the time she published her first novel, The Comforters, in 1957, which is more or less when Electric Spark ends. She was born Muriel Camberg in Edinburgh in 1918, a background evoked in her best-known and—boringly—best novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), about a delusional but charismatic girls’ schoolteacher, whichtook up almost an entire issue of The New Yorker and became a successful play and film. She moved to Southern Rhodesia in 1937 with her new husband Sydney Spark, and Africa provided the setting for a series of stories, including “The Portobello Road,” “The Go-Away Bird,” “Bang-Bang You’re Dead,” and “The Seraph and the Zambesi,” which won a national competition in The Observer (“Got it,” she wrote in her diary). In 1944, she left her husband and headed back to Britain. Her son was sent to be raised by her parents, and she moved to London and worked generating counter-intelligence propaganda (The Hothouse by the East River) while living in a women’s hostel near Hyde Park (The Girls of Slender Means), and later spent time as an editor, assistant, and aspiring writer (Loitering with Intent, A Far Cry from Kensington) and among louche men in various parts of London (The Bachelors, The Ballad of Peckham Rye).

In 1954, Spark suffered a breakdown, partly induced by appetite suppressants. She had been raised in a nonpracticing Jewish household, and flirted with Anglo-Catholicism, but now she became a wholehearted Roman Catholic. She described a version of these events in the novel she began writing very soon after, at the urging of the publisher Alan Maclean, who had noticed her stories, and with the financial support of Graham Greene, who had been contacted by Spark’s lover Derek Stanford about a gifted but struggling young Catholic writer.

Spark wrote consistently about artists and fiction writers. The Comforters concerns the wealthy horse-racing correspondent Laurence, his diamond-smuggling grandmother Louisa, and his on-off girlfriend Caroline, who is converting to Catholicism and working on a study of form in the modern novel when she discovers that she is being written into a novel, which may or may not be the novel we are reading, of which Caroline may or may not be the author. (Asked what her novel will be about, she replies, “Characters in a novel.”) In Memento Mori (1959), Spark’s third novel and first commercial success, elderly novelist Dame Lettie Colston and her group of friends receive telephone calls from God, or perhaps the author, reminding them they will die. Dougal Douglas, in the antic dark farce The Ballad of Peckham Rye (1960), travels to South London from Edinburgh to produce a report on local factory workers—taking into account “psychological factors,” and “observing the morals.” He urges himself: “Enact everything. Depict.” In the end, he gathers together “the scrap ends of his profligate experience” and turns them into “a lot of cockeyed books.” The emergence of literary talent was the subject of the most celebrated of her later novels: Loitering with Intent (1981), which takes place in 1949 and 1950, and turns Spark’s time at the Poetry Review, which she edited briefly,into the cultish Autobiographical Association; and A Far Cry from Kensington (1988), set about five years later.

In the time that Wilson covers, Spark also underwent her accidental apprenticeship, acquiring the resources to develop her style and worldview. Growing up in Edinburgh, she was inculcated in briskness of statement, an ease with paradox—it was the city of Jekyll and Hyde and the burglar-mayor Deacon Brodie—and the casual savagery of the Border Ballads, a copy of which she won as a poetry competition prize at the age of thirteen. On leaving school, she took a course in précis-writing. During the first half of the 1950s she wrote poetry, a critical biography of Mary Shelley, and the study of Masefield, and cowrote or coedited four books with her boyfriend and future enemy Derek Stanford. (Wilson is understandably drawn to a period when a formidable writer devoted her energies to biographical projects.) When Spark evoked those days in A Far Cry from Kensington,she turned Stanford into the “pisseur de copie”Hector Bartlett, and pointedly gave him a style that “writhed and ached with twists and turns and tergiversations, inept words, fanciful repetitions, far-fetched verbosity and long, Latin-based words.”

One of the remarkable things about Spark’s trajectory—and another reason Wilson is able to end her account in the late ’50s—is that her sensibility emerged fully formed. Loitering with Intent and A Far Cry from Kensington are written in the first person and emphasize the role of autobiography and autobiographical fiction in the education of a writer much like herself—the autobiographies of the Catholic convert Cardinal Newman and the painter Cellini in the first case, Charlotte Brontë’s Villette and Proust in the second. But the indispensable device in Spark’s own work—and a crucial innovation—was an authorial narrator, icily alert, controlling, and amused, at times even snide, who approaches scene-setting and psychology as if indifferent to earthly affairs, or newly acquainted with them:

Laurence was away all day, with his long legs in his small swift car, gone to look round and about the familiar countryside and coastline, gone to meet friends of his own stamp and education, whom he sometimes brought back to show off to them his funny delicious grandmother. Louisa Jepp did many things during that day. She fed the pigeons and rested. Rather earnestly, she brought from its place a loaf of bread, cut the crust off one end, examined the loaf, cut another slice, and looked again. After the third slice she began at the other end, cutting the crust, peering at the loaf until, at the fourth slice, she smiled at what she saw, and patting the slices into place again put back the loaf in the tin marked “bread.”

Ian McEwan, in his novel Sweet Tooth (2012), which is set in the 1970s, uses Spark as the case study during an argument about literary taste. Serena says that she enjoys early novels such as The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie because she likes to see “reality as I knew it recreated on the page.” Tom prefers “tricks” and is drawn to a more recent book. The Driver’s Seat (1970), nowadays perhaps Spark’s most cited work, was one of four novels, the others being The Public Image (1968), Not to Disturb (1971), and The Hothouse by the East River (1973), that she wrote under the influence of Alain Robbe-Grillet, the leader of the nouveau roman, who disdained the outmoded “myths of ‘depth’” and offered no description of characters’ thoughts or feelings.

But McEwan’s division is an illusion, a product of his taste for dichotomies. Spark had always been a writer in pursuit of strange effects. In a landscape dominated by mild social satire, the polemical drama of Angry Young Men, and later “kitchen-sink” realism, this was a central source of her appeal. The “tricks” were always there. During the near half century after The Comforters—her final novel, The Finishing School, appeared in 2004, two years before her death at age eighty-eight—you can see developments and dips, but the only real swerve was her attempt at what she called “a regular novel,” “a long book with a lot of scope,” The Mandelbaum Gate (1965), about a Jewish Catholic convert visiting Jerusalem during the Eichmann trial. Spark warned her British publisher to “stand by for my big flop,” and for expressions of regret that she was “going straight now.” And while the reception wasn’t rapturous, it became her only book to win an award, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. (She later won the third biennial David Cohen Prize for Literature, given for a body of work by a British writer in any literary form.)1

If anything, the early run of novels that “poured out” of her, as she put it, during the late ’50s and early ’60s—quasi-Gothic, often macabre comic portrayals of scheming and control – are more distinctive and original than the later attempts to produce a British nouveau roman. You could even argue that the more outwardly experimental work exhibits a slight loss of nerve. When Spark wrote The Driver’s Seat, in which a woman travels “south” to find the man who, we are told, will murder her, she consciously adopted devices used by other writers. The coolly factual present-tense narration came from Robbe-Grillet’s Jealousy, while the novel’s “trick,” telling the reader where the story is heading, was something picked up from the Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope. At the start of the third chapter, we read: “She will be found tomorrow morning dead from multiple stab-wounds, her wrists bound with a silk scarf and her ankles bound with a man’s necktie, in the grounds of an empty villa, in a park of the foreign city to which she is travelling on the flight now boarding at Gate 14.” Then we return to Lise the previous day, crossing the tarmac with “her quite long stride.”

Spark didn’t say when she took note of what Trollope had done, but mentioned it in relation to The Driver’s Seat. Some readers have also pointed to a similar effect in earlier novels, such as the sidelong, mini-spoiler announcement that one of the students in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie will perish in a fire (“Back and forth along the corridors ran Mary Macgregor, through the thickening smoke”), or this glimpse of the future in The Girls of Slender Means (1963), which otherwise takes place in 1945, when “all the nice people in England were poor, allowing for exceptions”:

“I’ve got something to tell you,” said Jane Wright, the woman columnist.

At the other end of the telephone, the voice of Dorothy Markham, owner of the flourishing model agency, said, “Darling, where have you been?” She spoke, by habit since her débutante days, with the utmost enthusiasm of tone.

“I’ve got something to tell you. Do you remember Nicholas Farringdon? Remember he used to come to the old May of Teck just after the war, he was an anarchist and poet sort of thing. A tall man with—”

“The one that got on to the roof to sleep out with Selina?”

“Yes, Nicholas Farringdon.”

“Oh rather. Has he turned up?”

“No, he’s been martyred.”

“What-ed?”

“Martyred in Haiti. Killed. Remember he became a Brother—”

“But I’ve just been to Tahiti, it’s marvelous, everyone’s marvelous.”

This revelation does not serve as a test of Spark’s thesis that, as she put it, “giving things away” doesn’t “at all take away from the suspense.” The Driver’s Seat has a single arc—we follow Lise as she tracks down a suitable killer, who then rapes and kills her. The book is an exercise in teleology, tracing a journey toward Lise’s end and the novel’s ending. Our knowledge that Nicholas will one day be martyred, the first thing we learn about him, adds an inevitable frisson to all the scenes in which he appears. But no one reads The Girls of Slender Means, a book about young women,to learn about the later life of one of their male suitors. The novel’s real ending is not revealed in advance. Updike, in his review, insisted that he would refrain from “plot-blabbing”: “the discourtesy seems double in the case of a writer whose plots are so pure.” Even Wikipedia, sixty-two years on, only discloses, “The narrative climaxes with a tragedy.” Nicholas’s violent death as a missionary in Haiti is an item of epilogue data. Flourishes of that kind are not related to the revealing of narrative information, Trollope’s trick, but Spark’s wielding of formal innovation to thematic ends—using her God’s-eye view and God-like powers to reflect on human fate, including the fate of Catholic converts.

Spark also found her own way to the eccentricities of her narration. The Robbe-Grillet influence came later. In a letter from August 1957, collected in the large and consistently revealing new book of Spark’s early correspondence, she says that she wrote “The Go-Away Bird,” her long story about a British girl in Africa, with “a vague ‘French’ style in mind.” The book’s editor Dan Gunn supplies a footnote on the nouveau roman and quotes the Spark scholar Michael Gardiner on Robbe-Grillet’s importance to The Comforters. But there’s no reason to believe this is the debt that Spark was acknowledging. The earliest record of her enthusiasm for Robbe-Grillet that I’m aware of doesn’t come until December 1960, in a books-of-the-year roundup, in which she wrote that she consumed his novel Jealousy “like a starving hawk.” The previous year she had reviewed a nouveau roman of sorts, Marguerite Duras’s dialogue-novel The Square, but after insisting that she was “the last person to object to . . . anybody’s larking about with the novel form,” she made it clear that she considered the book a failure.

The letter about “The Go-Away Bird” proceeds to explain that she wanted to describe “the destruction of innocence” and “contrast different social groups, and so demonstrate how illusions are destroyed.” This is not what the concertedly abstract Robbe-Grillet writes about. She was more likely thinking about Flaubert or Proust, or perhaps whatever she meant when four decades later she observed that Brontë’s Villette “has a touch of the French” and that Brontë must have been reading “some French novels.”

Spark’s decision to experiment with nouveau roman methods emerged from her conventional novel, The Mandelbaum Gate, and a scene in which she describes the Eichmann trial in the manner of the new French novels about “repetition, boredom, despair, going nowhere for nothing,” which the heroine is studying with her students: “Minute by minute throughout the hours the prisoner discoursed on the massacre without mentioning the word, covering all aspects of every question addressed to him with the meticulous undiscriminating reflex of a computing machine.” It was this passage, from the book in which she “went straight,” that unlocked Spark’s new tone, and a different—albeit more familiar and modish—variety of fleet flair.

Wilson, in contrast to Gunn, dates the influence of the nouveau roman to the later 1960s. Earlier resemblances had their origins in a kinship or shared temperament. As she put it, she had been “thinking the same thoughts” as writers like Robbe-Grillet, “breathing the same informed air.” She had “a bent towards” his kinds of habits anyway. And as she also emphasized, when she started out “there was no Robbe-Grillet. Hardly anyone was trying to write novels with all the compression and obliqueness I was aiming at.” One exception—which she may have had in mind—was Ivy Compton-Burnett, to whose influence Wilson devotes some illuminating passages. Another—which she almost certainly didn’t—was Henry Green, who also wrote acidic, dialogue-driven domestic comedies. But what Spark was doing had greater implications.

IT WOULD BE challenging—or straightforward but plagiaristic—to describe the character of Spark’s ambitions or her significance to postwar literature without reference to Frank Kermode. The leading British critic of his generation, the Renaissance specialist, prolific journalist, and sometime editor of Encounter, served as what Spark called “my explainer” for her entire career, from The Comforters to her collected poems in 2004 and beyond, reviewing Martin Stannard’s biography in the summer of 2009 and discussing the time-shifts in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie in his final book, Concerning E. M. Forster, which appeared later the same year. (A New York Times review of one of his early essay collections asked, “Who in 2001 will read the minor novels of Muriel Spark?”) In 1961, Kermode and Spark discussed myth and fiction as part of a BBC series transcribed in Partisan Review,in what Spark described, accurately enough, as “an oft-quoted classic interview.” The following year, after Spark had left London, they spent time together in New York, where Spark was living at the Beaux Arts Apartment Hotel, working in an office at The New Yorker, and socializing with writers and critics. (For a brief period, she had a crush on Lionel Trilling.) Spark was shocked when Kermode threatened to cancel a party in her honor following the news that Kennedy had been shot. In letters more than three decades apart, she told him she was “touched” by something he wrote about her work.

Kermode once confessed that it was easy to choose the new Spark novel as his novel of the year, not just because of “custom” but “some indescribable affinity.” Indescribable for him, perhaps, but not the onlooker. Kermode and Spark were almost exact contemporaries. They came from working-class families and received solid but not elite educations. They wrote the first books of their mature careers in 1955, and their talent was instantly recognized when the books were published in 1957. They were both accused of being aloof, to a degree that could seem passive-aggressive, even punitive, toward readers. The description of Kermode’s writing by the critic Michael Wood as “oblique, stealthy, lucid” could certainly be applied to Spark. Freddy, the amateur poet in The Mandelbaum Gate, is called “je-m’en-foutiste,” and Kermode describes himself with the same attribute in his memoir, though it’s unclear which of them learned it first. (Updike, in a line cut from his New Yorker review, defined je m’en foutisme as “don’t-give-a-fuck-ism.”) Kermode was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1991, Spark in 1993. Among regular contributors to the British press, they were perhaps the most likely to use words such as “quiddity” and “anagogical.”

The new book of letters reprints none of Spark’s correspondence with Kermode, and he makes only three cameos in the footnotes (one of them erroneous). But Gunn acknowledges Kermode’s importance, and the book ends by explaining that in December 1963, Spark wrote him that she was about to travel to the Virgin Islands “for a real live holiday which I haven’t had for years & doubt if I know how to have.” Another letter indirectly reveals Kermode’s understanding—or possibly, firsthand knowledge—of Spark’s intentions. Writing to Dwight Macdonald, she wondered how Robbe-Grillet could use his “abnormally detailed form” if the main themes aren’t “obsession, . . . jealousy, or voyeurism.” Kermode noted that Spark makes limited use of Robbe-Grillet’s techniques, to present “obsessed or manic states.”

But there was a fundamental difference in their sense of her work, at least in literary-historical terms. Spark said that she had been “enough of a critic to know what I wanted to do for the novel. It wasn’t by chance.” Realism was the orthodoxy, and here she was with a wild comic streak and God’s-eye view, a looser tone but a more severe treatment of character. When Spark described the “Gothic-rational synthesis” of Mary Shelley’s work, the Enlightenment component was established, the Romantic element fresh. She intended her own work to be a counter to the scientific perspective as embodied by the prominent physicist, civil servant, and avowed realist C. P. Snow, whom she admired—she chose The Affair as a book-of-the-year alongside Jealousy—but considered “a complete fantasist,” the deviser of a world in which “the human will is in charge,” and her opposite in “every possible way.” (Snow once called her “an author with one foot off the ground.”) Rationalism and realism, though inherently secular, reminded her of the strict Calvinism of her childhood, while her elective Catholicism was a liberation, enabling her to believe in absolute truth and the supernatural; she considered Cardinal Newman “a nineteenth-century Romantic.” (This is another reason why the resolutely anti-metaphysical Robbe-Grillet could not have been a formative influence.)

Spark as a Gothic or quasi-Romantic disrupter was the standard view, expressed by avid followers of the English fiction scene, such as Updike and David Lodge.2 But Kermode, adopting what he called “the long perspectives,” saw her intervention in more dramatic terms, as the latest response to a perennial struggle. On one side was the human desire for a consoling order, on the other a proper respect for contingent non-narrative reality. In Kermode’s view, order had predominated for too long. In Romantic Image he combatted what the myth common to Romanticism and to movements that considered themselves “militantly anti-Romantic,” that the artist was an isolated figure who, by virtue of this isolation, commanded special access to a phenomenon called the Image or Symbol that existed “out of space and time,” nearly autonomous, beyond confusion, turmoil, “the flux of life.” A key site and subject of this Image was the idealized, abstract Dancer. Spark tamed fantasy with formal rigor. In “The Seraph and the Zambesi,” for example—though it’s not a connection Kermode himself made—she drew a dancing archetype from Romantic literature, Baudelaire’s “Fanfarlo,” and placed him against the backdrop of a nativity play in Southern Rhodesia. An Observer reader complained that “The Seraph and the Zambesi” read like a blend of bedtime story and the worst of the American pulp “whodunits” (Updike preferred detective story and parable). And Spark projected a vision of the artist as busy, communal, involved, not just Caroline in The Comforters and Fleur in Loitering with Intent, but Cramer, the poet dressed as a seraph in the performance, who announces that he has rejected literature in favor of life.

To Kermode, Spark was part of a new avant-garde. In a 1959 essay on Joyce, he announced “the obsolescence of an aesthetic”—the Romantic approaches perpetuated by various kinds of modernism. Young readers were no longer interested in attempts to create “an entire self-supporting world.” But Kermode wasn’t convinced by the extreme alternative pursued by Joyce’s onetime disciple Samuel Beckett, in whose work the “signs of order and form” are simply “cheques which will bounce,” and the desert “in which we normally dwell” is afforded far more attention than “the delicious oases.” (Kermode later modified these characterizations.)

Seen through this prism, writing as an autonomous structure or as a futile howl, Spark actually resembled C. P. Snow in her belief in the possibilities of describing something, literature as referential. What mattered was not the presence of the fanfarlo in a piece of English fiction but that the fanfarlo was brought down to earth. In portraying Miss Jean Brodie as a dreamer, a know-it-all, and a fascist, for example, she drew a connection on which Kermode was himself insistent, between romantic fantasy, the belief in “total explanation,” and totalitarianism. This wasn’t to claim Spark as a literary realist. That would be fruitless. But in Kermode’s view, the religious perspective, in contrast to the Image, rested on an idea of mimesis, of reflecting reality, even if it was a higher reality. In a dizzyingly compressed passage in The Sense of an Ending (1967), he argued that everyday human contingency—the flux excluded from Romantic and modernist work—was allowed a place in Spark’s fiction, as the quirky or arbitrary-seeming products of a grander design.

It was certainly an unusual approach, optimistic even by the standard of writers averse to the desert-minded view. Kermode’s other favorite writer of the period, Wallace Stevens, found fleeting intimations of “concord,” moments of delight or respite, but not a “supreme fiction” that provides enduring consolation. Spark believed in absolute truth and that she could channel it. Though Kermode disliked the attempt to give literature a sacred status, and though he was not a Christian, he was convinced as well as seduced by Spark’s claim to find form and meaning in reality, or at least by her ways of articulating it in fiction.

What separated Spark and Snow from the tradition of the Romantic Image was a refusal to replace the world with an autonomous literary object. What separated them from Beckett was resistance to despair. But what elevated Spark above Snow was the exotic freshness of her solution. Whereas he responded to modernism by reviving the techniques he celebrated in his book The Realists, she harnessed her Catholic faith to address the challenge confronting the novelist—not yet identified as postmodernist—who was aware that modernism had run its course but unwilling, unlike some traditionalists, to pretend that it had never happened. Ideas of order were the subject of her work, an effort in which Stevens was her most obvious colleague. (She described the theme of The Mandelbaum Gate as “pre-laid plots in life.”) Here were two writers—soon to be joined in Kermode’s pantheon by Thomas Pynchon—engaged not just in what, at the start of The Sense of an Ending, he said that artists try to do, make sense of our lives, but in what critics do: make sense of the ways we try to make sense of our lives. (Yeats emerged as the hero of Romantic Image for making the artist’s isolation a “theme” and not just a “pose,” “complaint,” or “programme.”)

Spark said that while she writes, “I’m a critic all the way along. . . . I’m both a critic and a writer.” If her own version of what she was doing is a nudge, a local tremor, Kermode’s describes an overhaul or breakthrough. He wrote that she possessed the power to make a more “constitutional change” to the novel than any of the more overtly radical experiments—Beckett’s trilogy, William S. Burroughs’s cut-ups, Michel Butor’s idea of the novel as a search, Robbe-Grillet’s nouveau roman.

KERMODE, FOR ALL THE DEPTH of his insights, surely went a little far. He once wrote that if one of Spark’s books seemed pointless or artificial we must be “reading it lazily or naively.” And while he feared that he was lonely in viewing Spark as “our best novelist,” the truth was a little more nuanced. James Wood, writing near the start of this century, noted that everyone was always calling her that: “A consensus has closed like an eyelid.” He thought it was “almost certainly true.” He just thought it didn’t reflect too well on the state of British fiction.

To Wood, the things that Kermode admired were a source of frustration. He agreed that Spark was a theological writer, with an ability to be both literal and surreal. But as a lapsed Anglican who had embraced the novel, he was averse to a writer who treated fiction as a terrestrial intermediary, a pale imitation of “a truer realm.” Kermode believed that Spark’s work reconciled metaphysics to a respect for reality, arguing that an event in her fiction could stand for something else without sacrificing its concreteness. But Wood thought her work was not sufficiently invested in human reality or mystery—it was too controlling, too knowing.

Clearly this is a rarefied debate, conducted, based on distinctions unlikely to trouble the vast majority of readers. But those were the two positions: Spark as a visionary experimenter who retooled the novel from within, and Spark as a writer whose religious priorities rendered her a mere “diversionist” (in Wood’s term, borrowed from The Girls of Slender Means) or “trifler” (Kermode’s, channeling the doubters). In one, belief is an advantage, an unusual novelist’s tool; in the other it is a handicap, a limit on her identity as novelist. There’s no way to settle the matter, though it’s worth noting that in the worst-case scenario, Spark’s offering, whatever it shrinks from, was the richest available. Neither side denies her originality.

But a more skeptical position—the recognition of a sort of airiness or flippancy—wins out when we turn to the period beyond the new biography and letters. Spark’s “prime”—despite the obstinate complacency of headline writers—didn’t last very long. Wilson notes that Spark’s interest as a biographer was creative decline as well as “creative potency,” but her own work tends to treat the writer’s moment of emergence as a culmination. The Comforters and Spark’s unhelpful memoir Curriculum Vitae (1992) end with writers recovered from nervous collapse, newly converted, ready to write. Fleur, in Loitering with Intent, which ends in a similar way, reflects that the characters she created were “the sum of my whole experience of others and of my own potential self,” adding, “and so it has always been.” It may be that by solving so many problems at the start, she had nowhere to go—and became the author of mere divertissements that she was sometimes charged with being.

V. S. Pritchett, in a passage Wilson quotes in a different connection, claimed that the life of every writer contains a break, where “he splits off from the people who surround him and he discovers the necessity of talking to himself and not them.” There’s often a second break, after the artist has severed themselves from a formative environment, of being severed from the initial sources of their power, whether by success or publication, or having used up a fund of material. It calls for some kind of redoubling. Iris Murdoch, having, like Spark, followed a run of mostly sharp and impudent early novels with something more traditional (The Red and the Green),began to write more expansively, in an effort—successful, in the case of A Word Child, The Sea, The Sea,and The Philosopher’s Pupil—to introduce more contingency into her symbolic, shapely plots. Another contemporary, Penelope Fitzgerald, admittedly an unusual case in that she wrote mainly in her sixties and seventies, produced four novels that derived from personal experience—running a bookshop, living on a barge, teaching in a stage school, working at the BBC—before turning to historical subjects, culminating in The Blue Flower, a novel about the Romantic poet and philosopher Novalis, which Kermode praised for its interrogation of “the hopes and defeats of Romanticism” and “the relation between inspiration and common life.”

Spark met this challenge once, when The Mandelbaum Gate, a conscious break, yielded the exercises in nouveau roman. But when that mini-period ended, she didn’t manage it again. Most of her novels after The Hothouse by the East River—ten over the subsequent thirty years—are dinky, fleshless, flat. Wilson, adopting the limited time frame, doesn’t have to address the matter of Spark’s waning powers. Perhaps she wouldn’t have done so anyway, given that she considers Loitering with Intent and A Far Cry from Kensington the most “brilliantly achieved” of Spark’s novels. I hope it isn’t too presumptuous to say that the author of a study like Electric Spark may be slightly––and forgivably––blinded by gratitude for those books, as a resource. (I have certainly been guilty of a similar slippage when writing about novelists, including Spark.) It is the biographer’s version of Kermode’s excitement at the appearance in the late ’50s of a British novelist with an ambivalent attitude to Romantic tropes happy to admit that she thought like a critic. Though witty, vivid, and well-paced, those novels’ procedures seem more basic, the tone jauntier, the stakes lower, than in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, The Girls of Slender Means, or The Driver’s Seat. (After writing Loitering with Intent she told Graham Greene she found writing “I” books “cramping.”)

But even if the undoubted appeal of Spark’s late memoiristic novels may undermine the case for a steep decline, their origin in her early experience supports the sense that when Spark left London, first to live in New York, later Rome, and then for more than three decades Tuscany, she cut herself off from vital stimuli and was forced into backward-looking endeavors. The Only Problem (1984) concerns the writing of a book about the Book of Job, a project Spark herself abandoned in the ’50s; Reality and Dreams draws on old research into Roman Britain; The Finishing School describes a writer starting out and is set, like Frankenstein,in Geneva. Other books, like Symposium (1990), feel like a retread of old tropes.

One might point to a victory for Spark’s Romantic side—seduction by the old myth of the isolated artist. She didn’t go as far as Stephen in The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, who thought the artist could “have not even one friend.” Spark certainly had one—her longtime assistant and companion Penelope Jardine, who now serves as her executor. But it doesn’t matter how much of a magnet you are if you’re living as a literary grande dame in a fourteenth-century presbytery in the Tuscan hillside. That essential apartness, which she once characterized as “freedom from a lot of things,” found an external objective form in a certain chill circularity. The writing of Spark’s later years recalls that of Ernest Hemingway, returning to the scene of his first novel, The Sun Also Rises, for A Moveable Feast, or the other great British writer to emerge in the late ’50s, V. S. Naipaul, settling old scores from his seclusion in Wiltshire, and revisiting his—admittedly extraordinary—origin story for the umpteenth time.

But maybe Spark was bound to produce that kind of body of work. For all her cerebral resources, there was a ragged instinctivism to her approach, even to her craft, which, being grateful for it, and viewing it as akin to the poet’s fierce flame, she didn’t question or complicate. Toward the end of her life, she expressed a deep desire to know “what physiologists and psychologists make of the fact of inspiration.” That approach may have rendered her vulnerable. In a 1962 letter to Dwight Macdonald, she said she was “too lazy” to do multiple drafts as he did, though she acknowledged it might improve her work. “After all, the Holy Ghost did a lot of editing and revising of the Bible before he finally settled for the Vulgate at the Council of Trent.” And though she rewrote Territorial Rights (1979) after deciding the first version was “awful,” it was rarely her way, and she resisted “stylistic queries” and “suggestions for constructional changes.”A late starter, she displayed a kind of beginner’s luck—though she may have plumped for a less secular concept. At the end of Loitering with Intent, Fleur recalls the day that she kicked a passing soccer ball with “a chance grace which, if I had studied the affair and tried hard, I never could have done.” But in asking why she was no longer able to do it, we fall back to a feeling of delight that she ever did.

Leo Robson is a contributor to New Left Review and the London Review of Books and recently published a novel, The Boys (Riverrun, 2025).