THE MEME, IF THAT IS WHAT YOU WANT TO CALL IT, caught my attention sometime back in 2018 in the middle of Trump One, when things still were making a modicum of sense. Underneath a photo of the great man, smirking like a second-string high school quarterback who has just gotten his hand in a cheerleader’s pants, was the following passage from Catch-22:

It was miraculous. It was almost no trick at all, he saw, to turn vice into virtue and slander into truth, impotence into abstinence, arrogance into humility, plunder into philanthropy, thievery into honor, blasphemy into wisdom, brutality into patriotism, and sadism into justice. Anybody could do it; it required no brains at all. It merely required no character.

Well, that was refreshing! In the book this insight is delivered courtesy of the Chaplain, formerly a morally impeccable if spiritually hapless man who has checked himself into a hospital under false pretenses with an imaginary case of something called Wisconsin shingles. Sinning for the first time and “exhilarated by his discovery,” he foresees for himself an exciting future of moral turpitude precisely identical to the prevailing insanity of the bomber group he is supposed to be ministering to. This breakthrough insight mapped perfectly onto the unfolding spectacle of Trump and his metastasizing regime of idiot incompetence, unchecked corruption, bottomless mendacity, and feral indifference to human suffering.

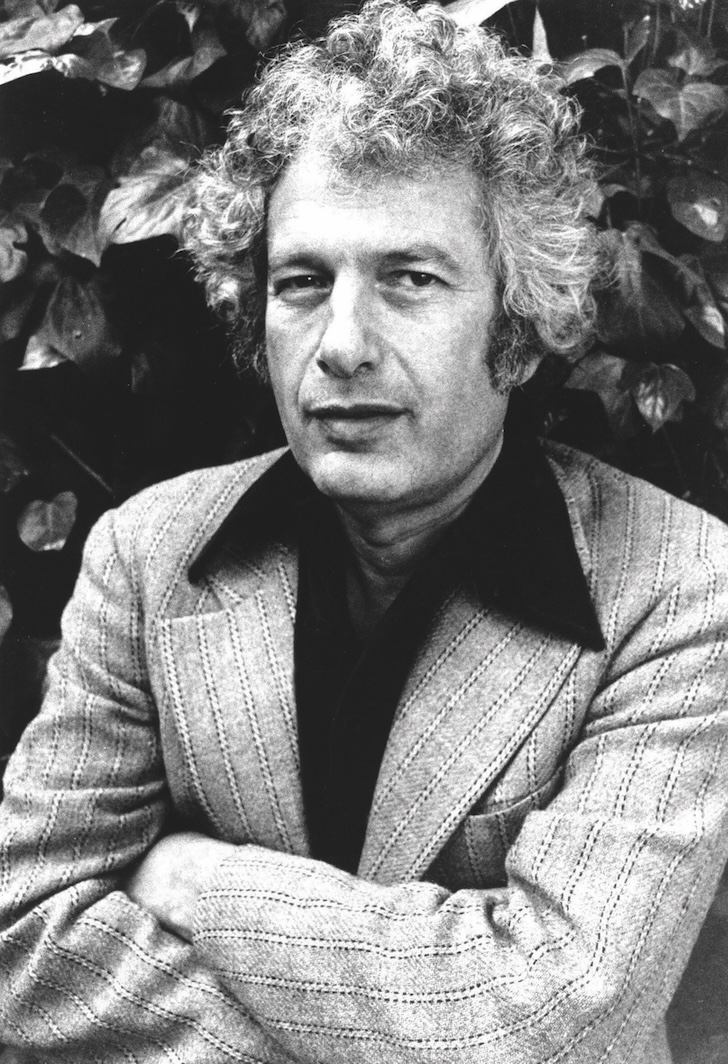

It had been years since I had thought seriously about Catch-22, and more than five decades since I had read it, but I tipped my hat to the far-seeing Joseph Heller and to the anonymous poster who had retrieved this passage from the book and applied it with such irrefutable rightness to the occupant of the White House. I liked it so much that I printed it out and taped it on my office door along with a photo of Robert Stone in short pants at age six waving a flag in front of the Federal Reserve Building on Wall Street and a tart quote from Flannery O’Connor about college writing teachers. I knew that by that point in its history Catch-22 had become a distinct back number and maybe even little more than a catch-phrase, no pun intended, for news commentators. But the book had once meant a lot to me, perhaps even everything, and I was doing my bit to keep the flame alive.

I had stumbled on Heller’s satiric masterpiece by mistake. I was thirteen years old in 1963, and my reading skewed heavily toward World War II subject matter, particularly accounts of resourceful British and American POWs escaping their prison camps (The Great Escape and The Wooden Horse) and of aerial derring-do (Great American Fighter Pilots of World War Two, a Landmark Book for young readers that I reread so often I had committed it to memory). My father had served in the war in the Army Air Corps, although as a radio operator in a DC-3 transport plane he had, disappointingly, never machine-gunned a Messerschmitt or Zero pilot to a fiery death. Almost twenty years after its conclusion World War II still took up a considerable amount of space in the popular imagination.

I had just finished reading a paperback copy of that cautionary tale of nuclear peril, Fail-Safe—this was a year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, remember—and I noticed an ad in the back for a book with the unusual title Catch-22. It was illustrated with a line drawing of a man wearing a flak jacket and a flight helmet and goggles against a side view of a B-25 bomber. Clearly a book right up my bloodthirsty street, so I borrowed a copy on my next trip to the Brooklyn Public Library and dug right in.

And it was . . . puzzling. But also intriguing. The novel was devoid of any acts of military heroism or patriotism or sense of duty. Where were the enemies they were supposed to be annihilating? The commanding officers were all self-serving and/or murderous poltroons concerned solely about their rise in rank. The pilots and crew members who went about their jobs with straightforward competence and resolve were seen, not necessarily as fools, but certainly peculiar and not fully clued in. Yossarian, a bombardier and the main character, should conventionally have been regarded as a coward for his avoidance of the ever-escalating requirement of missions, but we were, I began to understand, meant at some level to admire him for his dogged attempts to live forever or die in the attempt. The humor in the book was for me at the time more theoretically than actually funny, but the Abbott-and-Costello wordplay and the silliness and circular logic (Catch-22 itself, The Man in White in the infirmary, etc.) appealed to my pre-adolescent sense of humor and began to alter my evolving worldview. I especially enjoyed Yossarian’s irrefutable argument that pain was a lousy system for God to have devised to alert humans to bodily peril, and the master class the ancient Italian man delivers to a shocked airman on the immense superiority of the craven long-game Italian approach to civilizational survival over the heedless American way. I was also in the early throes of puberty and in my raging horniness phrases like “Nately’s whore” and “nipples like Bing cherries” carried a powerful erotic charge, as did the officers’ priapic revels in Rome while on leave. There was nothing like a plot that I could discern, narrative time was scrambled and repetitive, but something, probably the increasing incidents of horror and Yossarian’s mounting hysteria as the mission count itself mounts, carried me forward to the book’s shattering climax, when the bombardier, ministering to a wounded gunner named Snowden, sees his innards spill out. Ripeness is all, Yossarian thinks, bleakly inverting the meaning of that line from King Lear.

After finishing the book I was a different person. My Boy Scout/Catholic school idealism had been completely short-circuited, and I was launched on my subsequent career as a teenage cynic. Joseph Heller’s book had delivered a devastating dose of negativity and disillusion and damned if, not unlike the Chaplain, it didn’t feel right and good. My schoolyard jokes became more and more oblique in a failed attempt to reproduce Heller’s humor in a milieu that had little appreciation for it, and I became known as something of an oddball. But in what felt like my real life, my reading life, Catch-22 opened a door for me onto the kinds of scathing novels that led Alfred Kazin to dub that period in American fiction “the age of derision,” and I have never looked back.

I may have been an odd number in the cultural backwater that was St. Anselm’s grammar school, but all across the country Catch-22 in its paperback edition was having the exact same effect on millions more members of the baby boom generation. The timing was perfect for it. This was the great age of mass literacy and the paperback of the novel, priced at a mere ninety-five cents, sold in heroic and almost unheard-of numbers of millions and continued to do so for at least twenty years. The book’s bracing cynicism about the American military struck a nerve in a younger readership fed up with the unrelenting propaganda about American greatness in the Good War and the looming terror of nuclear annihilation that had arrived hard on the heels of its conclusion. The year after its publication Herman Kahn of the Rand Corporation had mused about the possibilities of limited nuclear war in Thinking About the Unthinkable, the insane “logic” of which—who can forget “mutually assured destruction”?—Stanley Kubrick and Terry Southern liberatingly lampooned in Dr. Strangelove for all time. In John Yossarian young people discovered a rebel with a cause, that of his own survival. The claim that “they” were trying to kill him resonated at a deep level with kids who’d ducked and covered under their school desks during air-raid drills. He was perhaps the most conspicuous antihero in a period where such figures were increasingly populating books and movies.

Heller’s antic and irreverent manner in Catch-22 quickly became a reigning literary and even national style. It was one of the first American novels that adopted and domesticated European absurdism, brought to these shores in the plays of Ionesco and Beckett and the fiction and philosophical musings of Kafka and the Existentialists, especially Camus. Heller had also taken literary inspiration from Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s pitch-black and stylistically headlong Journey to the End of the Night and Jaroslav Hašek’s classic antiwar satire The Good Soldier Švejk. Catch-22 helped unleash a wave of full-spectrum mockery of every aspect of American life and a slaughter of sacred cows. The critical term “black humor” arose to describe this new style and it was so ubiquitous that by 1965 Bruce Jay Friedman, one of the school’s founding tummlers, would assemble an anthology with that title that featured the work of Heller, Vladimir Nabokov, Thomas Pynchon, J. P. Donleavy, John Barth, Terry Southern, and others. In his introduction Friedman maintained that in America “there is a new mutative style of behavior afoot, one that can only be dealt with by a new, one-foot-in-the-asylum style of fiction,” an assertion famously echoed by Philip Roth.

Then, of course, the Vietnam War moved into high gear and the issue of survival was no longer abstract for a generation exposed to the perils of the universal draft. It seemed as if the Pentagon’s strategists had read Catch-22 as their war plan, and when on February 7, 1968, a hapless Army spokesperson told reporters that “it became necessary to destroy the town [of Ben Tre] to save it,” the novel and the bloody illogic of our conduct in that conflict became fused in the popular mind. Although Heller was never one of the highest profile literary opponents of the war like the grandstanding Norman Mailer and Robert Lowell and Doctor Spock, he did demonstrate and speak to student groups against it and was listened to as someone of great authority on the matter.

By the time the Vietnam War ended ignominiously Catch-22 had become canonical, but it had also begun its long slow fade. It did not help that the big-budget 1970 film adaptation by Mike Nichols was a notorious box-office flop and an artistic failure; a really good film on the order of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest would have given it legs in the broader culture. The film of M*A*S*H* and then the wildly popular sit-com spin-off leached away a lot of the book’s anti-establishment mojo.

But I suspect that Catch-22’s slide toward obscurity began in earnest once people felt it necessary to say to anyone in uniform, “Thank you for your service.” This pathetic civilian reflex would have begun around the first Gulf War, and it accelerated wildly once the fetishization of World War II veterans took hold in the wake of Tom Brokaw’s flag-waving The Greatest Generation and, especially, Steven Spielberg’s all-time male weepy Saving Private Ryan. It became more than a little inconvenient and even embarrassing that the best-selling American novel of the Second World War portrayed the military as being run by self-serving nincompoops and profiteers and war as a lethally irrational enterprise. And nothing that the chronically pissed-off critic and veteran Paul Fussell said or wrote could stem the flood of treacly piety on the subject.

But then both Catch-22 and its creator have occupied a shifting and anomalous position in the postwar literary scheme of things. Heller, as is widely known, was himself a bombardier in the war, flying sixty missions with the 340th Bomb Group out of Corsica. He’d enlisted in 1942 at age nineteen after an echt Brooklyn childhood and adolescence with friends named Beansy and Danny the Count. (One learns in Tracy Daugherty’s biography that Heller’s favorite book as a boy was a prose translation of The Iliad, which he read numerous times. This is suggestive on multiple levels, including the fact that the central characters of The Iliad and Catch-22 both spend a lot of time sulking in their tents.) Most of the missions Heller flew in France and Italy were so-called milk runs to bomb often undefended targets, as the Luftwaffe had been grounded by that time. But the German flak guns could be both accurate and deadly, throwing up shards of shrapnel that easily penetrated the thin aluminum walls of the B-25s. Bombardiers were cocooned in a glass enclosure beneath the flight deck, making them the most dangerously exposed of all the crew members to the flak.

Still the war seemed almost like an unexciting movie to Heller until his thirty-seventh mission, a harrowing flak-filled bombing run over Avignon. The copilot panicked and threw the plane into a near-fatal dive. Then a gunner was badly wounded by flak, and it fell to Heller to minister to him until they made it back to their base. This is the real-life basis of the harrowing Snowden episode in Catch-22. As Heller recalled in his Playboy interview, “I suddenly realized, ‘Good God! They’re trying to kill me too!’ War wasn’t much fun after that.”

In fact a startling amount of the characters and incidents in Catch-22 had their sources in real life, albeit often stylized and wildly exaggerated, as one learns in an exceptionally well-researched paper by Daniel Setzer, “Historical Sources for the Events in Joseph Heller’s Novel, Catch-22.” (If Simon & Schuster had known the extent of this, they might not have published the book for fear of libel suits, but Heller was less than candid in the vetting process.) When the novel became a sensation, some of the men in his outfit were quite bitter about the way that Heller had used their war experiences as raw material for, as they read it, laughs. One of his squadron mates wrote of it as an unforgivable betrayal: “No, there was no Catch-22—just someone who turned on his comrades and who did so long after the war was over when there was no one around to beat the living shit out of him.”

Ouch. But in fact Heller seemed to be in no hurry to turn his wartime experiences into fiction of any sort. Although he refused to fly for many years after his discharge, he does not seem to have been traumatized by them in the way David Nasaw has tried to convey in his recent book The Wounded Generation. In what might be called the Ernest Hemingway Sweepstakes, though, plenty of veterans were in a hurry, including Norman Mailer with The Naked and the Dead, Thomas Heggen with Mister Roberts, Irwin Shaw with The Young Lions, John Horne Burns with The Gallery, James Michener with Tales of the South Pacific, and unnumbered others with books published within three or four years of V-J Day. Heller did have serious literary ambitions, but he first realized them in a string of derivative short stories unrelated to the war published in Atlantic Monthly, Story, and similar publications. He studied English at NYU and Columbia on the GI Bill, went to Oxford on a Fulbright, and did two years in the purgatory of composition instruction at Penn State before returning to New York to work as a promotion executive for such large-circulation magazines as Time and McCall’s.

Heller has confessed to being at the mercy of the workings of his imagination, and the genesis of his most famous book proves it. One day at home the following sentences popped into his head: “It was love at first sight. The first time he saw the chaplain, _____ fell in love with him.” That as-yet-unnamed person turned out to be John Yossarian, and the whole subsequent book took shape in Heller’s mind almost at once. Within a day or so he’d written the first chapter of a book titled Catch-18 and sent it to his agent, the soon to be legendary Candida Donadio. She sold that chapter to the prestigious mass-market literary magazine New World Writing, where it ran in 1955 along with the first appearance of a book that would become On the Road. Two years later she sold a partial manuscript of the book to a young editor at Simon & Schuster, the also soon to be legendary Robert Gottlieb. The two men undertook the task of editing and revising Catch-18 in a leisurely and painstaking fashion, and it was finally scheduled for publication in 1961, when it had to undergo a change of title to avoid being confused with Leon Uris’s blockbuster novel of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, Mila-18. A frantic search for just the right new number ensued, and it is Gottlieb who claims to have hit on “22” as the right funny integer, although Donadio has her supporters in this regard.

Upon its publication, Catch-22 received decidedly mixed reviews, and its sales were initially slow. Conservative readers were greatly put off by its jokey and chaotic treatment of a subject of seemingly great seriousness. There had been irreverent service comedies before like See Here, Private Hargrove and Mister Roberts, but a book on the war written in the register of a demonic cackle was profoundly off-putting to some. Whitney Balliett’s response in The New Yorker was typical. He complained that the book “gives the impression of having been shouted onto paper” and dismissed it as “a debris of sour jokes, stage anger, dirty words, synthetic looniness, and the sort of antic behavior the children fall into when they know they are losing our attention.” But far more perceptive and enthusiastic responses and reviews arrived from the likes of Nelson Algren, Art Buchwald, Robert Brustein, and, yes, even the pre-neocon Norman Podhoretz, and a semi-underground cult of admirers began to amass. Simon & Schuster did its part with a dogged and clever advertising campaign that poured fuel on the commercial embers until a sizable blaze erupted. The book had sold a respectable, although not best-selling, 30,000 copies in its first year, and then Dell Publishing, the paperback publisher, ran for sales daylight.

Catch-22 is set during World War II, but Heller was not really being dilatory because, as he admitted in interviews, its real subject is the American 1950s. The Korean War, the Army-McCarthy hearings, the Cold War, and the total hegemony of big business over American life are the real targets of Heller’s satirical wrath. This accounts for some of the deliberate anachronisms in the book like a loyalty oath campaign and Milo Minderbinder’s slogan that “What’s good for M&M Enterprises is good for the country,” a slight paraphrase of “Engine Charlie” Wilson of GM’s infamous statement. We forget the scorn and dismay that the postwar American way of life ignited in the intelligentsia; in the course of researching this essay I came upon statements about President Eisenhower that might as well have been directed at Trump, so total was the disgust he ignited.

Heller’s literary career proceeded on its own highly individual and eccentric schedule and orbit, floating free of the zeitgeist’s calendar. Thirteen years would pass before he would publish his second novel, a miserabilist near-masterpiece of white-collar fear and trembling, Something Happened (1974), with its unforgettable opener, “Closed doors give me the willies.” Its narrator, Bob Slocum, is a mid-level executive for a large corporation, an impacted mass of unhappiness and unfulfillment and a spiritual kin of the fretful Organization Men from the Age of Conformism. This novel of male midlife angst seemed strangely timed for the tail end of the Age of Aquarius, but I read it just as I was entering the, ahem, workforce, and shaken, all I could think was, Thanks for the heads-up, Joe.

Fifteen years later Heller finally got around to writing his Jewish novel, Good as Gold, a slightly rancid portrait of Jewish family life seemingly calculated to make Irving Howe madder than Philip Roth ever managed to. Heller never evaded his Jewish identity, but Yossarian is identified as “Assyrian” in Catch-22 even though he is clearly recognizable as a classic schlemiel-victim from Yiddish literature, and Bob Slocum in Something Happened is utterly deracinated. Heller always seemed to operate a bit to one side of the most admired Jewish-American writers, not just the postwar pioneers and giants like Bellow, Malamud, Mailer, and Roth, but also figures like Doctorow, Ozick, Paley, and Elkin. He wasn’t really commercial, but he also wasn’t particularly literary in the standard sense of the word. He didn’t sign PEN letters of protest in The New York Review of Books or appear on high-minded panels or pontificate on the issues of the day. His affinity group ran more to show-biz figures like Mel Brooks and Dustin Hoffman and the novelist Mario Puzo. He even took low-prestige but high-paying jobs in Hollywood as a scriptwriter for the films Sex and the Single Girl and Casino Royale and an episode of the fairly lowbrow service comedy sitcom McHale’s Navy. Gore Vidal, who rated Good as Gold very highly, was onto something when he observed that “because Heller is a superb comic novelist with an eye and ear for American idiocies he’s never included on lists of novelists to be venerated.”

Joseph Heller died in 1999, his books after Good as Gold offering increasingly diminishing literary returns. One feels that while Catch-22’s status as reference is permanent, it is in danger of being forgotten as a novel to be read and learned from. In 1986, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of its publication, the critic John Aldridge could write of “its current status as a monumental artifact of contemporary American literature, almost as assured of longevity as the statues on Easter Island.” But by 2001 blowhard Harold Bloom would dismiss Catch-22 as “a Period Piece, a work not for all time, but for the 1960s and 1970s.” Two decades on from that verdict, any rescue mission mounted on the novel’s behalf must begin by scraping off its encrustation of OK-Boomer associations and attempting to relate Heller’s baleful insights to current realities.

Donald Trump to the rescue then, as it were. Now that our forty-seventh president and his coterie of malignant bozos have revived the ’60s-based insight that stupidity, venality, and illogic are the guiding principles of governmental, military, and institutional behavior, and perhaps human life itself, Heller’s book has a fresh currency. I reread the book for the first time in fifty-two years, and it retains its power to startle, amuse, and appall. It comes at the reader with a disorienting rush and one’s first impression—the one certain early critics never moved past—is of chaos and silliness. But stick with it and Heller’s careful design comes into play, and the famous set pieces were all as brilliant as I remember. The book also has the strong smell of terror and mortality, scents I was unable to perceive at thirteen years of age.

There was one sentence in particular that nearly struck me dumb. The lead bombardier Yossarian had led his squadron on a bombing run over Ferrara a second time to demolish a bridge they’d missed on the first pass. One of the bombers had crashed, killing its entire crew. Back in the briefing room, exhausted physically and emotionally, Yossarian has to contemplate the painful fact that “they had all died in the distance in secluded agony at a moment when he was up to his own ass in the same vile, excruciating dilemma of duty and damnation.” I think the moral heart of Catch-22 resides in those few grave words.

And what can the book tell us about our grotesque political situation, when it feels like we are all living on Pianosa now? One’s first impulse is to identify the Dealmaker in Chief with Milo Minderbinder, the supply officer and trader extraordinaire who scours the Mediterranean for the best price of every commodity and who bombs his own airbase because the financial reward is too compelling not to. The sentence “Milo had been caught red-handed in the act of plundering his countrymen, and, as a result, his stock had never been higher” tends to support that impulse. But Heller intended the character of Milo to be an amoral innocent, a pure creature of the market, and in this regard he more closely resembles the young techno-barbarians of Silicon Valley, who ransack human culture and destroy entire economies because it can be done for a tidy profit.

If Trump resembles anyone in Catch-22 it is Colonel Cathcart or perhaps General Peckem, supremely dense men incapable of any consideration beyond that of their own advancement and enrichment. Pete Hegseth of course could have fitted into the book originally without changing a well-gelled hair on his vacant head, and the spectacle of humiliating obeisance that Trump’s cabinet members display on a regular basis is purest Heller.

Inevitably one has to go back to Philip Roth’s famous 1963 lament: “The American writer in the middle of the twentieth century has his hands full trying to understand, describe, and then make credible much of American reality. It stupefies, it sickens, it infuriates, and finally it is even an embarrassment to one’s meager imagination. The actuality is continually outdoing our talents, and the culture tosses up figures that are the envy of any novelist.” Donald Trump and his minions would certainly seem to prove Roth’s point anew quite spectacularly, although Terry Southern, Bertolt Brecht, Jonathan Swift, and Alfred Jarry, individually or together, might well be up to the task of doing them proper injustice.

In my view, though, it was and is Catch-22 that best captures our deranging situation in all of its ominous bone-caught-in-the-throat hilarity. My guess is that the book has the legs, the longevity, to go the distance along with other permanently relevant satires like Gulliver’s Travels and Gargantua and Pantagruel. One thing you can always depend on is human stupidity and selfishness. Joseph Heller told us that. We just forgot it for a while.

Gerald Howard is a retired book editor. His book The Insider: Malcolm Cowley and the Triumph of American Literature (Penguin Press) has just been published.