JULIA IOFFE’S Motherland is a book about Russian women written for American women. The book, which identifies itself as a feminist history of modern Russia, condemns American feminism for its toothlessness, its inability to see beyond the safety that has shielded America’s women from the ordinary horrors of Russian life. Ioffe was born and raised in Russia and moved to America in adolescence and so became a woman here, a human testament to the reality of a world that her American neighbors believed impossible to endure.

In the introduction Ioffe provides an account of the educational and professional history of the women in her family. Her sister, an oncologist; her mother, a pathologist; her mother’s mother, a cardiologist; and her mother’s mother’s mother, a pediatrician. She goes on: “Our great-great-grandmothers were doctors. Another was a PhD in chemistry who, in the 1930s, ran her own lab and published scientific papers at a time when her peers in the West still needed their husbands’ permission to do much of anything. (Our other grandmother, for what it’s worth, was a chemical engineer who oversaw the lab at a water filtration plant that supplied the Kremlin’s drinking water.)”

Ioffe assumes that her American readers will surmise from this genealogical account that the women in her family are extraordinary daughters of extraordinary women. But such an assumption would be wrong, she claims; “measured against the history of their own country, the Soviet Union, the women from whom I descend were perfectly average people.” An average Russian is an extraordinary American. Ioffe will prove that sentiment to her reader over the course of five hundred pages. Pride is a constant feature of the book: even when Ioffe is disgusted by her home country, she is proud of the epic proportions of that disgust.

Ioffe’s tome reads more like a work of fiction by Gogol than a history book or a family memoir. Motherland offers a view of humanity that is terrible but also recognizable. Men with political power do kidnap and rape young women; women do trade autonomy and self-respect for the fearsome protection of male providers. Americans are less comfortable with the omnipresence of evil than Ioffe is. The substance of Ioffe’s writing is charged with life and death—readers get used to praying that each introduced character will evade a terrible death and secure a life for her children—but the language is direct. It taunts its readers with breathtaking precision and dizzying details. She does not need to ornament with adjectives—the content shrieks for itself.

Readers will ingest an astonishing mass of facts, which Ioffe draws on in her affecting historical, cultural, and political analysis. But even more mesmerizing is Motherland’s rendering of several extraordinary women. Some of those women are Ioffe’s ancestors, and—mere Americans that we are—we believe they are extraordinary because accounts of their courage and iron stomachs gleam alongside accounts of the women who managed to etch their names into the history of a brutal patriarchy.

Women carry this book on their backs. Men are mentioned in relation to the women they impact. Virtually all the figures readers come to know through Ioffe’s work are not the people who crafted the policies that entranced, shaped, and destroyed modern Russia, because women were excluded from any such power. There is no way to tell an ordinary history of the same period without hyper-fixating on the specifics and interrelations of a handful of powerful men. Motherland is refreshingly free of such fixations, which means that it does not tell the story of modern Russia by stringing together a series of salient political events. Instead, readers become acquainted with the motion of that history through the way it sways women. History, in Ioffe’s universe, is the story of how women lived and survived through a set of circumstances dictated by men with power over them.

These circumstances are brutal. One of the axioms of Ioffe’s Russia is that brutality is a constant feature, like the cold. In the febrile week during which I inhaled Motherland, I often saw the book in my dreams, encrusted in a sheet of snow and frozen blood. There are four people who now live in that space in my imagination. Their names are Alexandra, Eleonora, Yulia, and Emma.

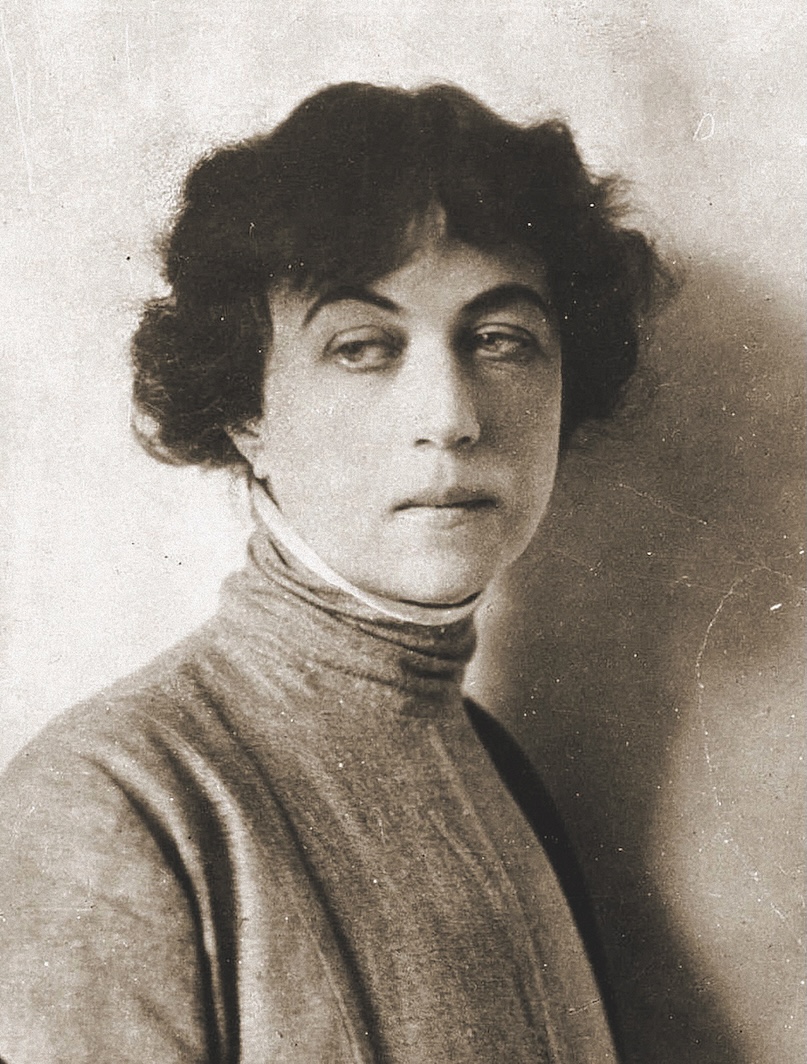

ALEXANDRA

One woman more than any other was responsible for extracting the promises that the Soviet Union would go on to break to its daughters. That woman was Alexandra Kollontai, “the world’s first female cabinet minister and first credentialed female ambassador for a country that would put the first woman in space, two decades before Sally Ride.” Kollontai would not have called herself a feminist. Feminists were bourgeois hacks who wanted to “drink the blood of the revolution.” Kollontai addressed the injustices that Russian society imposed on its women through socialist means. The ultimate enemy, she insisted, was capitalism, not misogyny. But because she was the highest-ranking woman in the party, she could articulate the oppressions that capitalism imposed uniquely on women in language that her male colleagues could comprehend and then repeat. She explained that pregnancy was a form of labor that should be subsidized by the state along with health care, maternity leave, and nurseries, whether the woman was married or not. Bourgeois marriage, Kollontai taught, was a form of female sexual and financial slavery, but socialist marriage, with the proper values and framework, would redeem the institution and The Family with it (Kollontai herself had practiced auto-emancipation by leaving her four-year-old son behind with her parents in St. Petersburg while she went to join the revolution).

Kollontai believed that it was a strategic error for the party to ignore the Women’s Question. It should have been easy for them to secure the support of working-class women whose loyalty was instead snatched by feminist activists who had no interest in dismantling the existent social order. She tried to convince the Bolsheviks that it was in their interest to exert effort to appeal to women recruits, but the men refused to take her seriously. As Ioffe puts it, “The Bolsheviks may have aimed to transform Russian society, but they were also products of that society, one that was still deeply patriarchal—and patronizing.” Still, Kollontai made progress. One way of measuring the failures of the Soviet Union is to track how the institutions and policies that Kollontai designed were abandoned or perverted.

She was a central figure in Lenin’s inner circle. Kollontai and eight other members of the party voted along with Lenin in favor of a coup in October 1917. Lenin made history four days later when, as the undisputed leader of the new regime, he appointed Kollontai head of social welfare. As Ioffe notes:

Kollontai’s writings became the blueprint for Soviet family policy. Maternity leave for eight weeks before and after childbirth became standard. . . . New laws established the equality of husband and wife in marriage, divorce, and property ownership. No longer did the wife have to take her husband’s name or follow him if he moved. Moreover, the two citizens were no longer called husband or wife but were each referred to by the gender-neutral “spouse,” both in legal documents and in life. Divorce was legalized and simplified. . . .

Rights that women in Russia had sought for decades were granted to them seemingly overnight. Universities now had to accept women, and all educational institutions had to remove any specification of gender from their titles. The 1918 constitution stipulated that every citizen was required to work and to receive the same minimum wage, regardless of gender.

Kollontai’s victories were reversed with Lenin’s death and Stalin’s usurpation of power. Stalin was an efficient man and a primitive one. He flourished in the patriarchal sludge in which much of Russian history had mired its citizens, and he restored the little that had been washed away with alacrity. For example, in October 1920 the Soviet Union had become the first country to give women the right to free abortions—the Family Law of 1936 made the practice largely illegal. But more than any policy reversals, the brutality of Stalin’s reign was responsible for the pitch into which Soviet women were forced to live. The poverty, the starvation, the paranoia, and the pressure to reproduce and then raise enormous families all affected women differently than any man.

ELEONORA

Kollontai had fought for a feminist Eutopia. Her heirs—the women of the Soviet Union—lived a kind of nightmare that American women of their generation could not imagine. Hava Volovich, a Jewish Ukrainian woman, was twenty-one when she was arrested and sentenced to a decade and a half in the Gulag. In that frozen hell she thought often about the salvific hope a baby would secure for her. In 1942 she gave birth to that hope and she named her Eleonora. Hava and Eleonora had a brief period together in a bedbug-infested hut with two other mothers and their babies before the pair was transferred to a mothers’ camp. There Hava was forced to fell timber while her baby was placed in a detkombinat, literally a “child plant.” Hava bribed the women workers who ran the “plant” to permit her regular entry and so she witnessed the unmitigated misery in which her child was destroyed. She watched nurses rouse the babies from sleep each morning by punching their tiny backs, and stared as one woman with a pot of porridge fresh off the stove walked from crib to crib tying each baby’s arms behind each tiny head before forcing the scorching slop down each small throat. The last time Hava held her baby, the child beat her small fists against her mother’s face until Hava gave in and restored Eleonora to her crib. When the mother comes back a few hours later her daughter is dead.

YULIA

Motherland is a feminist history of modern Russia, but it is also a work of feminist philosophy and the fruit of a powerful woman’s particular, exacting conception of what a woman ought to be. Ioffe has an image of the perfect woman, and her closest incarnation is Yulia Navalnaya.

By the end of Motherland we have ripened; we know that there are ordinary Russian women and extraordinary ones. They are in this respect exactly like every other female population. But Ioffe has given us a framework for evaluating a woman’s worth and so we can recognize by the time we meet her that Yulia Navalnaya is all a woman should be, and through her we understand a fundamental element of Ioffe’s framework, one we could not have understood before. We had to encounter five hundred pages’ worth of horror for us to know that the most impressive strength a Russian woman can develop is steel integrity in the face of despair.

Yulia Navalnaya is famous because she was a hero’s wife and she is now a hero’s widow. In Ioffe’s telling, Navalnaya’s husband, Alexei Navalny, was the only man to ripple the ocean of hopelessness in which Russian liberals of his and every subsequent generation will now be forced to live. Readers encounter Alexei through the prism of his wife’s breathtaking strength. We already know his story. We know that he managed to convince the dormant Russian opposition that a different future was possible. Even Ioffe admits that “[she] had come to believe him. [She] had, without even noticing it, bought his promise of a post-Putin Russia.” Some years earlier, when Ioffe’s father discovers that his daughter has decided to study Russian history and literature in college, he warns her against yoking her future to a country that has none. At the time, Ioffe was a sprightly undergraduate who, against her precocious better judgment, had absorbed the bubbly bath of American optimism in which she had spent the better part of her childhood. She told her father he was wrong, but after Navalny’s imprisonment Ioffe had sobered. “Russia’s future would never be different from its present or its past.” As if to punish herself for the frivolity of her faith in Navalny’s promise, in Ioffe’s universe his murder becomes a synecdoche for Russia’s sentence to eternal savagery. And Yulia Navalnaya’s sustained strength in the face of that despair gives shape to Ioffe’s ideal.

Once, early in his political career, Navalny and a colleague were unexpectedly sentenced to years-long sentences in a penal colony. Navalnaya watched as the pair were led away in handcuffs. The other man’s wife wailed and clung to her husband’s neck and members of Navalny’s team appeared shell-shocked, tears streaming down their faces. Navalnaya did not dissolve. “These bastards will never see our tears,” she said. Years later, when her husband came out of a coma and was unable to recognize her or leave his hospital bed, Navalnaya trained herself to get through each day by breaking it into small tasks. “‘Right now, I’m doing this, and then I will do that, and after that—something else,’ she said of her mindset. ‘And then maybe later, I’ll let myself cry.’” But if she happened to start crying while on a phone call, she’d force the tears to run silent. No one, not the friend on the line, and not whoever was listening in, would know the sound of her shattered resolve.

EMMA

The intimate urgency that vibrates throughout Motherland is fueled by Ioffe’s feral loyalty to the land she left behind. That loyalty is localized in a single person, Emma, Ioffe’s maternal grandmother. Emma was seven years old when World War II broke out. Her father, Isaak, was deployed to a plane factory to churn out warplanes—a necessity in such short supply that the factory did not have time to build living spaces for their workers before arrival. Isaak slept nights in the open fields in which he worked during the day. Emma’s mother, Riva, had saved up her entire life and trained hard for a degree in pedology, but in 1936 the Central Committee outlawed the discipline—“If it were true that a child’s entire life was predetermined by biology and environment, then how could the Communist Party build a new Soviet person?” and so she had to go back to school for a second degree that she earned just before the war broke out. She spent the start of the war trading medical services for food when Isaak’s salary from the plane factory fell short. She fainted regularly from exhaustion and hunger.

Turns out they were the lucky ones—Riva’s sister and her nieces were among the roughly three thousand Jews who were slaughtered in a Ukrainian ghetto called Medzhybizh in September 1942. Decades later Emma confided to her granddaughter that she was convinced her cousins had been buried alive. Ioffe tells her readers that it is not possible for her grandmother to have known the specifics of those deaths, just as Emma could not have known the details of how her grandmother, Riva’s mother, Ethel, was murdered in a pogrom in Ukraine during the Civil Wars twenty years before World War II. Everyone in the family knew Ethel was among the seven Jews killed during a particular pogrom; one account had it she was murdered inside the town’s synagogue. Ioffe’s mother, Olga, said that Ethel and her husband, Gersh, were tied to a wagon and dragged to their death, but Emma insists that Gersh was shot and Ethel was hanged in the town square a day later.

Emma is the heart of Motherland,the pulsing link between a sepia past readers can hardly imagine, and Ioffe’s sharp, vital presence. Ioffe was born in the Soviet Union, and she lived there for her first seven years under Emma’s flashing eyes. When Ioffe’s parents decided that the Soviet Union was no place to raise two Jewish daughters, the decision pierces and Emma is the human blade that allows the reader to long for a country we have been learning to fear. When Ioffe explains that to Emma, her daughter’s desertion is a betrayal, that Russians condemn Russians who leave, we Westerners have marinated in the rich chill that produced Emma long enough to sympathize with the sting even if we cannot understand it.

And twenty years later, when Ioffe returns to the Moscow apartment in which Emma is still living, readers recognize a homecoming we cannot fathom. Ioffe has come back as a correspondent for The New Yorker expecting to find a country in which the extraordinary women who people her family are so common they seem ordinary. She is disappointed. Her assessment that “Women there were obsessed with men—as husbands, as sugar daddies, as inseminators”—is laced with bitter disillusionment.

The acknowledgments that close Motherland end with a pledge to Emma, the grandmother who died before Ioffe completed the book. Ioffe confides that since Emma’s death, she has given birth to a baby boy named Isaac after Emma’s husband. She assures Emma that her great-grandson will be a worthy heir. This despite knowing that her baby may never visit the city Emma loved. Ioffe tells us she dreams of Moscow almost every night, nightmares in which she gets lost in a home that has become strange and populated by strangers she cannot ask for help.

What does it mean to raise children yoked to a past that has no future? What strength and wisdom could prepare a mother for that impossible task? These are the questions that Motherland answers, and they are more relevant for American readers today than they were when Ioffe first put pen to paper. The year 2026 greets us in a world that looks increasingly like the one Ioffe conjures. Brutality is a metastasizing feature of contemporary life. We have to learn to live with that.

Celeste Marcus is the executive editor of Liberties Journal and the author ofChaim Soutine: Genius, Obsession, and a Dramatic Life in Art (Public Affairs, 2025).