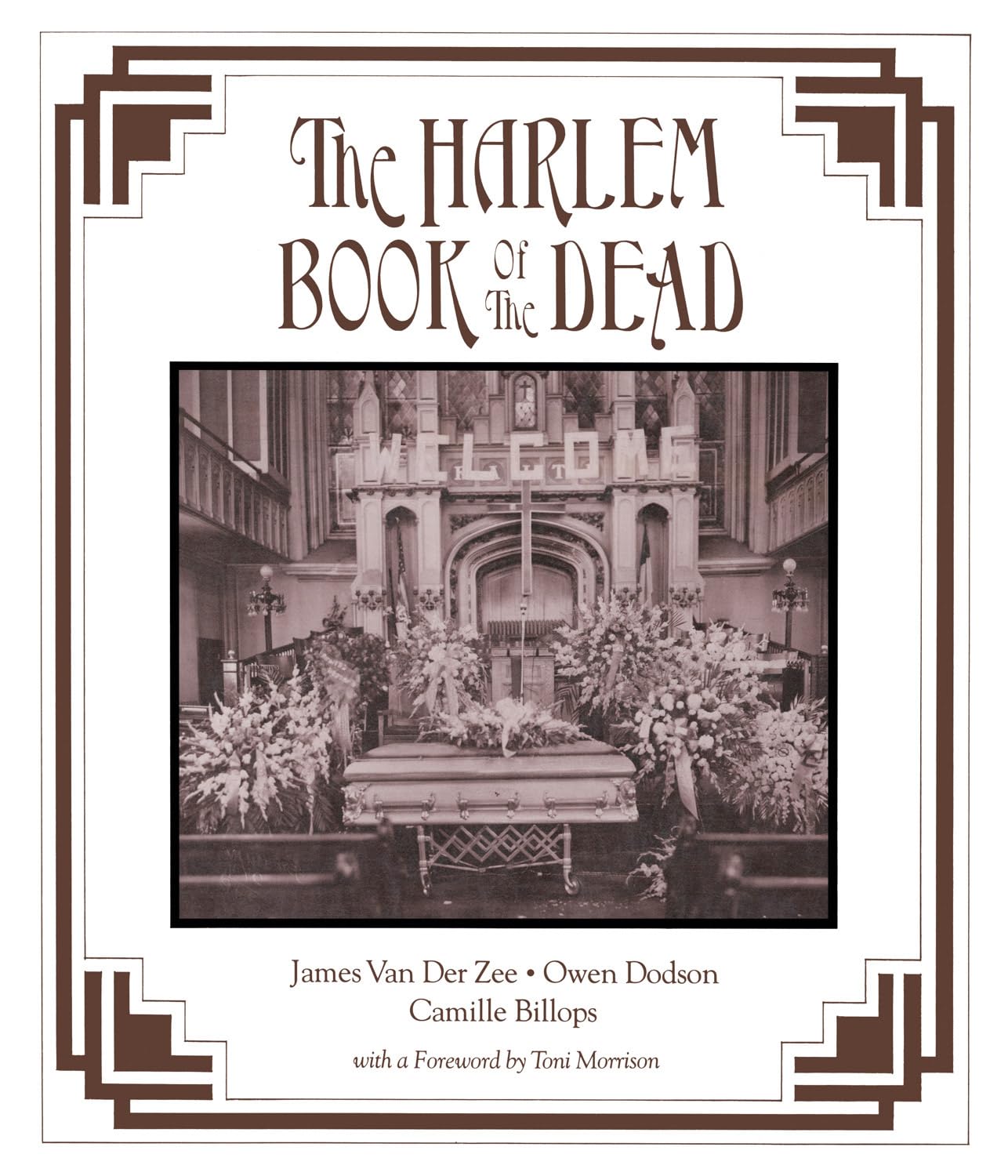

DEATH IS A LIVELIHOOD FOR THE GRAVEDIGGER. Death is alive. Death lives in Harlem. As Sun Ra expands in poem/song: death speaks to the negro, you are my servant. Photographer James Van Der Zee and poet Owen Dodson, guided by the vigilant curatorial eye of Camille Billops, collaborated to create a book documenting death in Harlem, first published in 1978 and reissued in 2025. The Harlem Book of the Dead, complete with an introduction by Toni Morrison in which she echoes “how living are these portraits of the dead,” treats every funeral for a black man, woman, or child as part autopsy and part spectacle, wherein the deceased body is tenderly reanimated like a performer who died onstage and still managed to deliver the encore. These private civilian funerals made public like those of dignitaries, these photographs of bodies in their open caskets and family members posing with said bodies, become one anonymous silent procession with no beginning or end, a jazz funeral for the dead and an eternal renaissance of Harlem’s low-exposure vicious modernism, to quote Amiri Baraka (Harlem is vicious modernism / vicious the way it’s made). That uncanny viciousness characteristic of Harlem itself and its dead as depicted here is further animated by Dodson’s exuberant and confrontational poems and the tense interview with Van Der Zee conducted by Billops, in which she pries into aspects of his private life, looking for substance that she does not find. The more she demands, the more he prickles and withholds—undertaker not overseer, he seems to whisper—refusing to glorify his process or exploit details of his personal life to explicate his creative impulses.

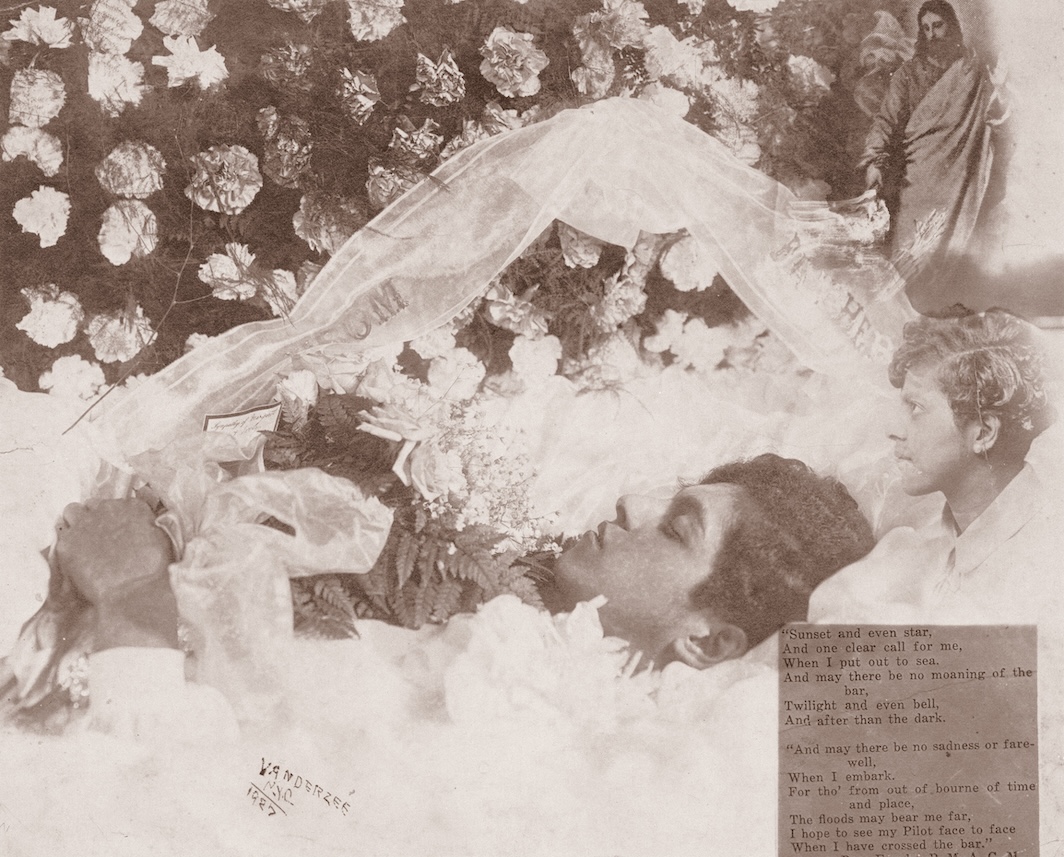

She interrogates him on his first marriage to a distracting extent, but manages to extract very little depth of feeling. We learn that Van Der Zee is not very sentimental about death or estrangement. His daughter Rachel died at sixteen, and when Billops asks if photographing her in her casket was difficult, he says no, because she was raised mostly by her mother, from whom Van Der Zee was estranged. His aim, he noted, was to make people (even the dead) look better in his photographs than they did in real life, but otherwise he exerted minimal effort to cast himself as pious or reverent of the subjects. He did this work in the darkroom, superimposing glory and seraphic light like a record producer might reorient a recording session for an album to enhance its emotional power. It seems Van Der Zee took meticulous photos of funeral rites and dead bodies because someone had to, as a devout cultural functionary, and because it meant there was an emergent black middle class or elite with enough agency and money to record their lives and not just live them at the mercy of wages and die in obscurity. They would exceed themselves in the afterlife by way of these visual documents, which are both routine and ornate fantasies about ascension.

There is little discussion of being haunted by these subjects or indebted to them. Van Der Zee’s primary concern is with their self-transcendence in his images, even if this means becoming props or wayward commentaries on the vanity and decadence of modern grief. Some are adorned with white angels added in postproduction or a grotesque excess of flowers to beatify them and unsettle the otherwise unsettling lividity of the lifeless human forms. Some strike the eye as between phases, as if the soul is being interrupted or making one final complicit terrestrial gesture before exiting the body. Some appear to be napping or in repose and not dead, like a baby who just fell asleep in his crib and woke up in the underworld. The photographs have something to tell us that the poems don’t reach; they are shrill in moments and quiet epitaphs elsewhere. One, called “The Children,”melodramatically laments the death of the young, we’ll never sleep again.Another, in the voice of a pastor, reassures, be it resolved, resolved, resolved.There’s a call-and-response between the dead and the mourners that the photographs mediate and hush.

As the images and psalms accrue, they begin to feel like betrayals, flaunting black likenesses as ephemera or some new kitsch anthropology to which none of the departed souls consented. Who said they wanted to be trapped on these pages together like a world’s fair exhibition on the expiation of black suffering in the afterlife, or propaganda for resting in peace, the polite petit-bourgeois-adjacent dying in the reformed Harlem. There are fallen soldiers in uniform beside toddlers with their panda stuffed animals, white angels, white flowers, elegiac poems that thrash at the frills of the images with imagined biographies projecting browbeaten weariness onto the subjects, who look ready to stop performing and really cross over. Rumors of bodies shifting in their graves come up in the interview. Van Der Zee is as unfazed about this as he is about every topic Billops addresses. He’s just doing his job; he’s a very sensual cypress for hire, he can make you live forever in at least two dimensions. The chemistry between him and Billops is off in transcription, like she’s punting biases at him and he’s dismissing them or deflecting before they yield to hysteria or too much self-congratulatory whimsy. Either that or his manner of speaking, which conveys a resistance to self-examination or emotionalism, contradicts the brooding and rollicking inflections of his images. He uses a veneer of vernacular art to give us access to the surreal qualities of these decorous funeral rituals, and to the mysticism in this series of images of vivified black death, in which the many are the one, the strangers are intimates in the afterlife, the familiars can’t quite seem to speak to one another candidly, and their dead are the better communicators of creative freedom.

This book is both an autonomous museum and a campy pamphlet you might expect to discover at a novelty shop. It is incompatible with any canon or common trope, though books like Amiri Baraka’s In Our Terribleness and James Agee and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men respond to and extend its coda. And since it is not didactic, either, its function is as a performance, a group show, collapsing in on itself, failing, where failure is the most effective way to express an unacknowledged and disconcerting dysfunction, or malfunction. We are grieving like beggars who hope to be included in history and not at all on our own terms. We are conducting white funerals for black people who live black lives and pretending to reconcile this as a symbol of progress until this tome becomes a brochure for dignified but unfinished and violating goodbyes.

Thumbing through Amiri Baraka’s book of eulogies, I happen upon one for Owen Dodson, which describes him with gloating affection as the leader of a theater group to which Toni Morrison belonged while at Howard. This explains his ability to turn strangers into a cast in conversation in thisbook of the dead. Where the Egyptian book of the dead teaches how to enter eternity correctly, this version suggests that eternity enters us and we either oblige or are buried alive with inanimate objects. And then I dig up a photo Van Der Zee took of his wife and daughter; they are glowing, ascending from the earth like two Persephones, holding hands in a mysterious forest on the banks of a shallow river with a plank for crossing by the child’s feet. The girl cradles a thin white doll, her mother a bouquet of autumn leaves. The mother’s free hand is balled into a limp fist. They gaze intently in opposite directions as if listening to two different songs on the end of the world. This is eternity! This is the photographer’s heart bursting with regret, longing, and revision that he projects onto them. The dead are not nearly as haunted as the living.

If you want to understand the purgatory between stages of grief as it lingers between spectacularly self-aware and helplessly aloof, or the narrow passage between sacred ceremony and pageantry, or the way a renaissance demands its adherents sacrifice the nihilism of more stagnant eras, here is the record to play and loop. In 2025, I want to add to it the imaginary photograph of James Baldwin at his father’s funeral on his twentieth birthday in 1943, and the day an uprising broke out in the streets of Harlem, as he describes in Notes of a Native Son.And I want to add Michael Jackson in 2006, doting over James Brown’s lifeless body the night before his funeral and then again the day of, at Harlem’s Apollo Theater, and the strange photo of a half-nude black angel holding up a photograph of Langston Hughes at his imagined funeral, and finally images of Roberta Flack’s service in 2025 at Abyssinian Baptist Church. This is a book full of alternate endings and words that refuse to steal the meaning-making away from images which refuse to signify—a beguiling, voyeuristic dream worth abiding.

Harmony Holiday’s Life of the Party is forthcoming from Semiotext(e).