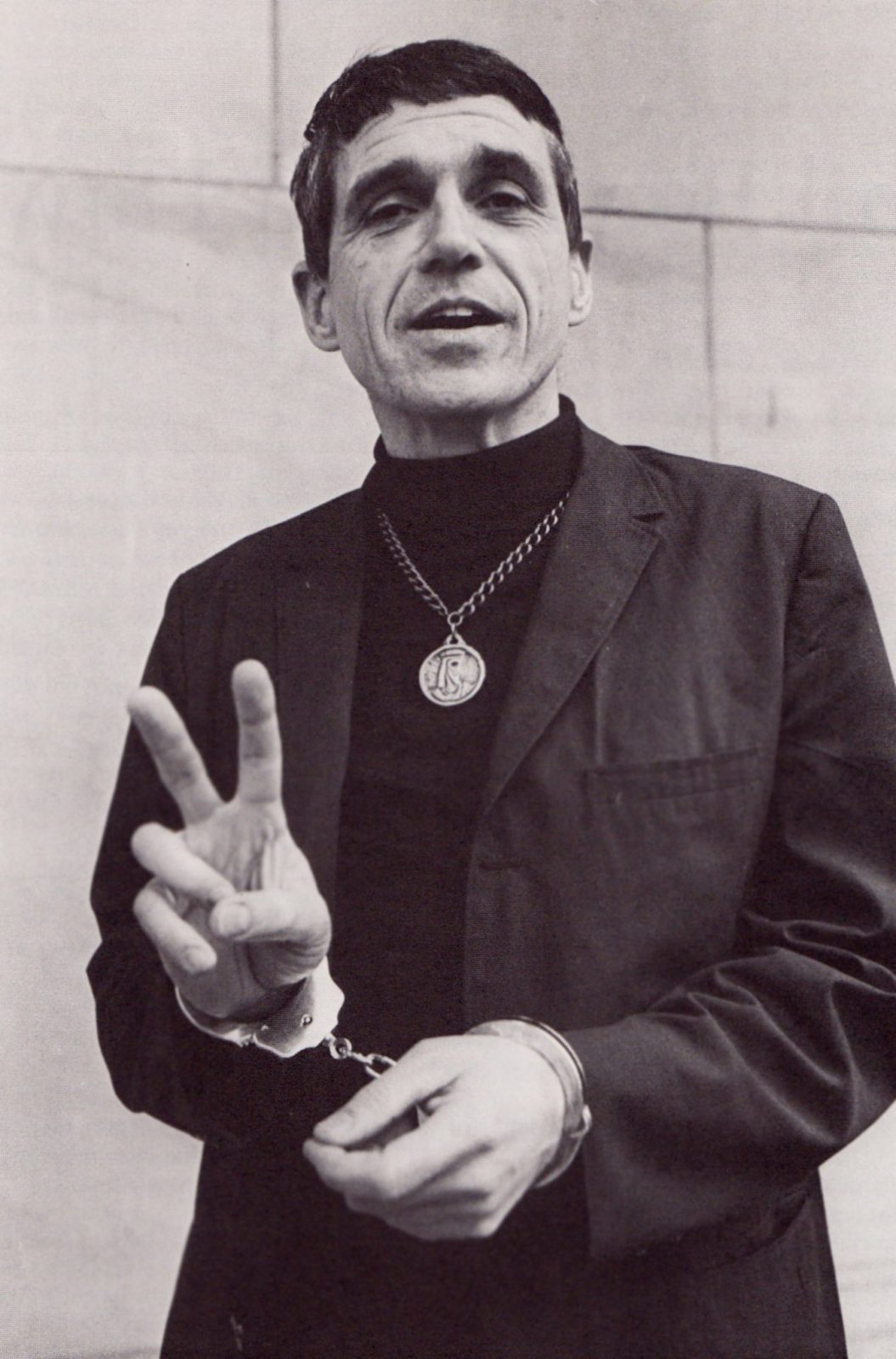

FATHER DANIEL BERRIGAN TURNED FORTY-NINE WHILE HIDING FROM THE FBI IN THE SPRING OF 1970, though pictures from that time suggest the playfulness of a younger man. In shots taken by civil rights movement photographer Bob Fitch, Berrigan mugs at the camera from under a rat’s-nest wig and sombrero, a lampoon of disguise. Beanie-clad, he grins in a parking lot while holding a Coke, takes a comically large step in sparse woods, smiles in a daylit diner booth at someone out of frame. At Cornell University’s Freedom Seder, part of a multiday festival thrown in his honor, he flashes a peace sign from the stage, sunglasses pointlessly and conspicuously on. He’d planned to surrender himself there, then decided not to, and escaped.

He analogized going underground to dying, to “closing the lid of a tomb,” and wrote of the loneliness that came with the necessary separation from family, especially his hospitalized mother. Yet “what fun!” he thought after he evaded the FBI at Cornell in, famously, an oversize puppet costume. As a wanted man, he released public missives, granted interviews, even spoke from the Sunday pulpit, and so humiliated the federal agents in flat-footed pursuit. (Time called him “a modern Pimpernel.”) He made fugitivity look social, invigorating, the closest a lifelong celibate could come to being a rock star. “I am thriving to the point of obscenity,” he wrote to his brothers two months in. Three more months would pass before he was captured on the verge of eating an apple in theologian William Stringfellow’s Rhode Island home.

He was sentenced to federal prison for burning draft-board files in Catonsville, Maryland, a crime committed in 1968 alongside eight other Catholic peace activists, one of whom was his younger brother Philip, also a priest. In footage recorded by the press they’d summoned to the event, participants take turns stating their purpose, affirming their mutual culpability, and explaining how they made the napalm they used as an accelerant. “We were all part of this,” one of the men says as each person sparks and then drops a match onto the already flaming pile.

Daniel was last to join the group that rallied to Philip’s vision, and therefore never meant to play spokesperson. But his statement during their trial defined the group’s action, and probably still constitutes his most famous lines: “Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the front parlor of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise.”

Catonsville was a formative rupture for Daniel, who’d been forging a path of religious rebellion since the nuclear bombing of Japan inflamed his misgivings about Catholicism’s complicity in war. Three years before, in 1965, Daniel’s Jesuit superiors exiled him to Latin America after he gave a homily for Roger LaPorte, a twenty-two-year-old Catholic Worker who self-immolated in front of the United Nations building in protest of the war on Vietnam. The church deemed LaPorte a suicide and therefore ineligible for a funeral mass. Berrigan legitimized the service with his presence, but that provocation paled in comparison to his sermon, which likened LaPorte’s death to Christ’s (“a gift”) and decried a populace, including the priesthood, that abdicated peacemaking. Supporters fasted, demonstrated, and petitioned for Berrigan’s return to the States with a full-page New York Times ad, which brought his name to a wider public. The superiors relented after four months. “I came home,” Berrigan wrote in his 1987 autobiography, To Dwell in Peace, “worse than ever.”

Berrigan landed at Cornell, where the students were restive, and school administrators, along with a majority of the faculty, were as vindictive and obstructionist as the church. It was 1967, two years into the draft’s dramatic increase, with roughly half a million American men deployed in Vietnam. Philip, a soldier before he entered the Josephite order, began to plan the destruction of selective service files in Baltimore, but Daniel wasn’t ready for such decisive intervention. He saw himself as a supporter of those directly engaged, not someone who thrust his own wrench into the state’s murderous gears. Six months later, after a trip to Hanoi, this—he—changed.

“I knew that he felt, after coming back from North Vietnam, that somebody had to cry out in the streets,” recalled Berrigan’s travel companion, Howard Zinn, in the 1970 film The Holy Outlaw. (The two were tasked with representing the American peace movement as they collected and escorted home three captured air force pilots.) Hours after they landed in Hanoi, they received an American welcome when they were jarred from sleep by an air-raid siren. The men spent a good portion of their trip sharing bomb shelters with the peasants under attack.

“It is a bit like Selma,” Berrigan wrote. “We are only safe among the victims. A law of history? Who was ever safe among executioners?” Amid the devastation his country inflicted on their homeland, Berrigan was shaken to his pacifist core by the Viet Cong hosts’ dignity and “astonishing” sense of purpose. They articulated a near-indisputable vision of the good life: individuals were given what they needed to thrive, dialogue was integral to decision-making, hierarchy was minimal, and women and children had the same rights as men.

When shown the darts, traps, and homemade guns of earlier Vietnamese revolutionaries, Berrigan rejected them as “not for me, any more than the planes and missiles of the Americans.” Yet he was inexorably compelled by Ho Chi Minh, from the leader’s fortitude in prison (“it seems to me only a true revolutionary would keep a diary in the form of poems”) to his devotion to his people. Berrigan could not imagine a pope or American president conducting himself with such an unfailing commitment to the poor, but it wasn’t easy to wed Ho’s Christlike qualities with the museum-showcased weapons. Could “moral superiority” ever belong to someone willing to harm other human beings, or was this “the old lie in a new guise”? He ventured no answer or endorsement but confessed that “the society here gives me more hope for the control and integration of violence than does our public experience at home.”

Two certainties towered above his ambivalence. First, the United States was enacting a wanton, rapacious genocide, “in violation of every international convention from The Hague in 1907 to Geneva in 1929 and 1949.” Second, the United States would continue to brutalize people within its own borders unless the “enormous, deformative power of militarism and nationalism” was interrupted. Though he saw Christians as especially negligent, he thought that Americans of all creeds refused the responsibility incumbent upon them, treating even modest protest—like marching—as a distraction from real life, a moral “extra,” and resigning themselves “to endure a great worsening and rotting of the public fabric.” This sickness of soul could not be healed by habitual behavior, political or otherwise. The moment required nothing short of conversion, a profound and complete change of heart. “An act of faith by modern man,” he wrote, “might begin by not asking for a clearer situation than the one he is in.”

Zinn and Berrigan’s Hanoi trip took place in February 1968. In March, President Lyndon Johnson authorized a troop surge in Vietnam. In April, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Countrywide riots ensued, bringing injuries, death, and Johnson’s invocation of the Insurrection Act to deploy the military in Washington, DC, and Chicago. Before the month was out, Columbia University called in the NYPD to tear-gas, beat, and arrest over seven hundred students protesting the school’s militarism and racism. In May, when Philip again approached his brother about destroying draft files, Daniel agreed.

Berrigan wrote steadily, indefatigably, from the 1960s until his death in 2016, and published more than fifty books of poetry, conversations, and prose. But the insights recorded during this spate of intense activity—Hanoi, Catonsville, Danbury prison (where he served eighteen months of his three-year sentence before release)—remain especially electric. Some of this lasting resonance can be attributed to imperialism’s recursivity; pages and pages of his Vietnam-era analysis map seamlessly onto the genocide in Gaza and prestigious universities’ barbaric response to protesters. “The Vietnam years, as I had undergone them at Cornell, had sealed the fate of the universities,” he wrote in 1987, deeming colleges “apt tools of the warmaking state.”

Primarily, though, the work’s power is in its tone, the expression of a mindset and emotional orientation that animates language the way breath animates body. During the late ’60s and into the ’70s, Berrigan, the wordsmith, managed something remarkable. He leavened his prophetic, Old Testament anger—at America’s foul, murderous past and present; at the Catholic church’s shameless centuries of bloodletting—with warmth and even sweetness.

Consider the humility and care in his message to white radicals the Weathermen, recorded when they, too, were fleeing the authorities. “I have a great fear of American violence, not only in the military . . . but also here, in me, up close, among us,” he said.

On the other hand, I must say I have very little fear, from firsthand experience, of the violence of the Vietcong or Panthers (I hesitate to use the word violence), for their acts come from the proximate threat of extinction, from being invariably put on the line of self-defense. But the same cannot be said of us and our history. We stand outside the culture of these others, no matter what admiration or fraternity we feel with them; we are unlike them, we have other demons to battle. The history of the movement, in the last years, it seems to me, shows how constantly and easily we are seduced by violence, not only as method but as end in itself.

This expansiveness was made possible by his move from anti-war commentary into illegal action. In crossing that border, Berrigan uncovered a wellspring of inherently hopeful energy that fed ambitious dreams. Liberation for him in these years included abolition of empires, nation-states, militaries, prisons, and that bastion of consumer culture, the family—which he faulted for isolating women while instilling selfishness in both parents. (“If we are talking about which structure in our society seems to offer the greatest resistance to change I would say, yes, it is the family,” he told the conservative-minded academic Robert Coles, and when Coles asked if Berrigan thought married men “lose their social compassion,” Berrigan replied, simply, “Yes.”) He engaged with the work of Eldridge Cleaver and George Jackson, cited Frantz Fanon, provided the foreword for a book called Quotations from Chairman Jesus, and wrote long, sincere letters from prison to the men who put and kept him there: Catholicism-loving Protestant J. Edgar Hoover and Danbury’s Catholic warden. “I wanted to announce the gospel,” he explained, “because they have never heard it.”

When photojournalist Lee Lockwood asked Berrigan in 1972 to respond to the criticism that he had been a “media freak” while evading the FBI, he replied, “I make no apologies to the mortician culture for playing around a bit. . . . One of the most sorrowful features of life today is that people can’t associate a kind of overflow of good humor and joy with the struggle.” Because the nature of the state is to use violence, and the nature of violence is to kill everything other than itself, “the recourse of decent men is constantly narrowing rather than widening.” Self-sacrificing creativity—an experimental act conceived in love, of which the enactor assumed full consequence and brought injury upon no other—was the corrective, a method for making possibility available in the otherwise viciously limiting present. As Berrigan said while underground, “I am more determined than ever to continue with this kind of life, for all its hazards, as long as it is possible.”

That daring, buoyed spirit endured briefly past his prison sentence, helped along, perhaps, by considerable celebrity. Daniel’s time underground lasted months longer than two other Catonsville participants who refused to report for the start of their prison terms: Philip Berrigan, caught in under two weeks during a raid on Manhattan’s Church of St. Gregory, and George Mische, captured in Chicago with agents’ guns drawn, a fact that infuriated Daniel beyond measure. Nurse Mary Moylan used a network of supportive women to stay free for an astounding nine years before she turned herself in. But it was Daniel—erudite, white, university-linked, and male—who captured the public’s interest. Postprison, teaching and speaking requests abounded.

His most infamous performance is also one of the most impressive. In a 1973 speech to the Association of Arab University Graduates in Washington, DC, Berrigan condemned at length, with rigor and sophistication, Israel’s crimes against humanity, which then as now were committed with American funding and oversight. The country had “passed from a dispossessed people to an imperial entity” and was threatening to become, in “a tragedy beyond calculating, . . . the tomb of the Jewish soul.” In Berrigan’s extensive, accomplished bibliography, it vies for the strongest offering.

“How strong is the irony of this occasion,” he reflected, with typical forthrightness, “a member of the classic oppressor church calls to account the historic victims of Christian persecution”:

Human life today, if it means anything, is meant to raise a cry against legitimated murder. Our lives are meant to be a question mark before humanity, whether we are Arab, Jew, or Christian. When a Zionist or American Catholic or an Arab Apologist loses that momentous dignity, he becomes a zero, his soul is torn in two.

Berrigan said he was indebted to and informed by “the vision Jews have taught me, of human conduct in a human community,” adding that his Christianity required that he “ask of Israel those questions which Israel proscribes, ignores, fears. Where indeed are your men of wisdom? Where are your peacemakers? Where are your prophets? Who among you speaks the truth to power?”

Scandal duly followed, stoked by coverage in The New York Times, a publication Berrigan had, for years, regarded with sublime disdain. (The article concluded with a complaint that Berrigan had given the speech to an Arab rather than Jewish audience.) Commentary magazine ran more than four thousand words condemning his “malicious invention and crude distortion” at a time “when Israel urgently needs . . . the simple human recognition of its basic legitimacy.”

Just as his early sympathy to leftist arguments still leads detractors to label him, inaccurately, a Communist, Berrigan has been maligned as an anti-Semite even after his death. He was, of course, familiar with condemnation and institutional punishment for his beliefs. But this insult, coming “from friends of long standing” who hurled it publicly, wounded him. It is one thing to be a respected gadfly, rejected by those you bedevil, and another to be a pariah, abandoned by those who once joined your chorus.

IN THE LATER ’70S, BERRIGAN WAS STILL, AS HE WROTE IN A LETTER TO PHILIP, “carooming [sic] around the country” on various public engagements, and writing copiously, but his health was diminished, and he suffered from problems with his back and eyesight. He provided hospice care for men with cancer and, several years later, with aids, as well as tended to his dying friend Lew Cox in what he described as “a little like a marriage—at least the closest I’m likely to get.”

Berrigan became a critic of homophobia in the church and decried women’s exclusion from the clergy, but his refusal to tolerate violence in any form, for any reason, set him apart from formerly admiring leftists and even other Catholic peace activists. At a group dinner in 1978, he was goaded by Maryknoll priest Blase Bonpane, who in Berrigan’s telling “support[ed] any + all gun-wielding Latins,” including Fidel Castro. True to his peacemaking core, Berrigan was unwilling to argue, particularly when someone wanted a fight, and so stayed silent until he couldn’t any longer. Bonpane’s final words, shouted at Berrigan’s back, were “too bad you can’t face these things.”

Another point of division arose after Roe v. Wade, when Berrigan began to speak publicly about abortion. One 1974 speech was, by his own report, “ill-received” by “a large group of women” whom he cruelly described as “wounded mothers of aborted children.” In 1977, Canada declared him an “undesirable alien” after an antiabortion speech in Ottawa, the text of which is not publicly available. In an essay from 1980, Berrigan, characteristically undeterred, reiterated his conviction that the procedure is “personally maiming” and claimed he had “yet to meet a person involved in an abortion who is not haunted by that memory.” (A foreseeable state of ignorance for a man best acquainted with other men, and nuns.) “I speak clumsily and wound many,” he confessed, adding that it was “terrible, a new defamation, to be named a hater of women.” Could he not access the former sensitivity and curiosity that might have tempered his position or at least its expression? “Anything like a revolutionary stance requires that one’s love stay stern as well as tender,” he wrote in 1968—a wise obligation he struggled to fulfill.

Writers expose themselves, inadvertently and unavoidably; prolific writers reveal even more. By the late ’70s and into the late ’80s, Berrigan’s writing suffered from incursions of bitterness and self-aggrandizement. Even as he excoriated the rottenness of his claimed institutions, he was flattered by association, proud to be a Jesuit and proud to have been at Cornell, which he routinely reminded readers is an Ivy League school. He repeatedly insisted, unprompted, that he cared nothing for society’s emoluments yet, in his writing, indulged in alternate realities of worldly success (in academia, as a writer, and as a compliant, rank-climbing priest). He claimed he conjured these could-have-beens to rest in the satisfaction of rightly rejecting them and, occasionally, this claim rings true, as when he wrote to Philip about seeing some Jesuits “pushing their golf bags ahead of them to a car. . . . I thought, there but for you, went I.” More often, there is a sourness to his later writings, a dishonesty—the ongoing struggle with pride denied yet evident on the page.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in his massively disappointing autobiography To Dwell in Peace, in which, among other frustrations, he erases Mary Moylan by claiming he “was the sole survivor” of “the undergrounders.” By 1975, fellow Catonsville participant George Mische stopped entertaining interview requests about that fateful day, explaining in 2013 that “the seeming infatuation with our event” distorted the era and marginalized hundreds of other activists. (He found the attendant mythmaking and overstatement “embarrassing.”) But Berrigan continued referencing Catonsville in his work as if it were as consequential as the bombing of Hiroshima—which, of course, in his life, it was. More so, in fact.

Berrigan’s writing to and about Philip was almost unfailingly beautiful. “Upon this single relationship has been built every other one in which my life rejoices,” he wrote in 1969. But Daniel’s greater celebrity, and what Philip perceived as his brother’s ego, caused rifts of resentment. After traveling abroad together in 1989, Philip wrote to Daniel that they “shouldn’t work together again without a better understanding,” saying he felt patronized, not listened to closely, and not treated like an equal during the trip. “I, condescending?” Daniel replied, condescendingly. “Come off it.”

The ego’s ugly comforts may have been irrefusable given Daniel’s loneliness—so intense in 1973 that he considered adopting a child—and the grueling, ongoing ordeal of harboring no illusions. Berrigan had long spoken of the Christian imperative to embrace powerlessness, calling the expectation of efficiency and productivity “debased.” Thinking in numbers and milestones, whether that be money, votes, memberships, or other “body count” metrics, risked fetishizing outcome, inevitably at the expense of means. “I don’t believe that Christians are called to win anything,” he said. They were only called to obey the teachings of Christ, to walk a path that could not be quantified.

But futility is a heavy burden, perhaps the heaviest a human being can be asked to bear. In 1980, after witnessing a child’s slow death from cancer, Berrigan gave vent to an accusation he rarely shared in earlier work. “What part does God have in such crime?” he asked—and answered. “This part. He does not intervene. He is silent. . . . I call him to account for this. . . . I will be slow to forgive.” Pages later, another dark disclosure: “One must admit the possibility, rapidly assuming the form of the probable, that things are all over for the human adventure. I have been battling this sense for some time.”

DANIEL’S FINAL DRAMATIC CRIMINAL ACTION was undertaken in September 1980, with Philip again at his side. Joined by six others, the brothers entered a General Electric facility that manufactured nuclear missiles. There, they damaged equipment with hammers and poured their own blood over documents, birthing the ongoing Plowshares movement. All eight participants were convicted but, after nearly a decade of appeals, released on time served: a slap on the wrist, by Daniel’s own formulation. Danbury would remain his sole experience in prison.

Philip, however, through dogged civil disobedience, was incarcerated repeatedly until his death in 2002. He felt called to witness in prison while Daniel didn’t, and the discrepancy threatened a friction that Philip tried to mitigate. “This is the best contribution I can offer,” he wrote to Daniel from prison in 1978. “Not so with you; you have so much more to give, or you have a wider diversity of gifts. . . . I read your stuff and say, my God! Look at my slop and look at Dan’s.” Philip seems to have divined—correctly, I think—that Daniel’s work was a source of shame for him when held against the sacrifices of his cohort.

One of the great questions of Daniel Berrigan’s life pertains to writing, not only his, but all of it, everywhere. Is it service or is it evasion, work or retreat, contribution or cowardice? Shortly after the Plowshares action, he wrote, “One had best stop playing the old academic-ecclesial game of Scrabble as though merely putting words together could make sense of moral incoherence, treachery, meandering apathy—could break that spell.” And yet he wrote; he wrote that rejection of writing, and much besides. Dozens of books came after Plowshares, including his remarkable exegeses of the Old Testament (Lamentations read in the light of 9/11; Kings through the lens of George W. Bush’s two terms). He believed in the transformative power of language almost helplessly, despite himself, which is to say he was a poet, or a revolutionary, or a prophet.

And part of his revolutionary, prophetic vision was his condemnation of the language of the powerful, which he described as a lethal pollution. “Words of corrupt diplomacy appear to me more and more in their true light,” he wrote in 1968, “as words spoken in enmity against reality. And that of course is a very old and carefully specified sin.” In an age of AI propaganda, we are reminded daily that “there is a perversion worse than evil deeds. . . . It is to misname evil as goodness, to exalt it, parade it, honor it.” It helps to read someone say so, like a gas mask for the soul.

Words are inadequate and disappointing, yet we need them. (People, too, are inadequate, disappointing, and indispensable.) Speech can be less than action, depending on what is said, or as sadistic as killing, as when it’s designed to “destroy the meaning of man’s life in the minds and hearts of others.” But it can also, as in the case of the prophets, reveal the only ground in which the seeds of worthy action can grow: the truth. The truth alone “liberates when everything else bespeaks slavery, untruth, deception, and violence.” It must be discovered, and stated, again, then again, from within and against the occluding despair.

The speech Daniel Berrigan gave in court after his Plowshares arrest is another of his triumphs, famous and oft-quoted, with good reason: “The only message I have to the world is: We are not allowed to kill innocent people. We are not allowed to be complicit in murder. We are not allowed to be silent while preparations for mass murder proceed in our name, with our money, secretly.”

But before that, integral to that, he made a confession. “The push of conscience is a terrible thing,” he said: “With every cowardly bone in my body, I wished I hadn’t had to enter the GE plant. . . . And that has been true every time I have been arrested, all those years. My stomach turns over. I feel sick. I feel afraid. I don’t want to go through this again.”

He was driven to surpass his fears by “a towering question, which has faced so many good people in history, in difficult times, now in the time of the bomb. What helps people? . . . What helps? That was a haunting question for me.”

Charlotte Shane is a writer, the founder of TigerBee Press, and the cohost of the podcast Reading Writers.