WE’RE IN THE HOLYOKE MALL, and I need to go to the bathroom. Although the divorce is not so recent, some activities with my father still stretch him beyond his inclinations or means, usually both, which he devises to suit my older brother and me to make up for “it.” Shopping at the video-game store is one of them, and I know going to pee could well cost me. I can’t help it. I slip away—my father and brother talking—and hope my absence won’t be noticed. Ideally, no time will pass at all.

I run to one end of the mall, double back.

“You need help?” asks a man, short with a round face, smiling.

“I’m looking for the bathroom.”

“It’s a little confusing,” he admits. “I can take you there.”

He likes to play video games, too, he says. My dad doesn’t, I reply. Dads are like that sometimes, he chuckles. It feels good for him to agree with me. He holds the restroom door open. I pass in front, our bodies close, and head to the urinals.

Here, I feel awkward—but a familiar weirdness. I have trouble peeing around people and the block compounds the longer I can’t go. Surely a man in my proximity can hear that I’m not peeing, which of course means there’s something wrong with me. I’m girlie or gay. I also don’t want anyone seeing my penis: it’s not as big as my father’s or brother’s (even now I want to re-qualify him as older).

“I have to go, too,” the man says, saddling up.

There weren’t dividers in those days, not at the Holyoke Mall.

The man unzips, looks down at me—my hands, my penis. I can’t move, let alone pee.

“Stage fright?” he asks, shifting his weight. He opens his stance, “Maybe I can help you? If you help me?”

The restroom door swings open, and another man lumbers in. I feel my soles again and, with a flush of shame, run off. I’m back with my father and brother. They’re still talking. No time has passed. For them. My dad buys me a game; I’m lucky. I don’t recall ever peeing.

When I think of me, the man, and the Holyoke Mall, I’m young—nine or ten. But I see now that the game Shogun was released in the summer of 2000, so I was actually fourteen. I’m young in the memory because as it was being formed I’d regressed, cowering and stunned. Over the years I’ve wondered: Why did my body freeze in that restroom? Why had I trusted this stranger, even appreciated his attention? What would’ve happened if the door hadn’t opened, breaking whatever spell had been cast? Why didn’t I tell my father, anyone, about the incident afterward?

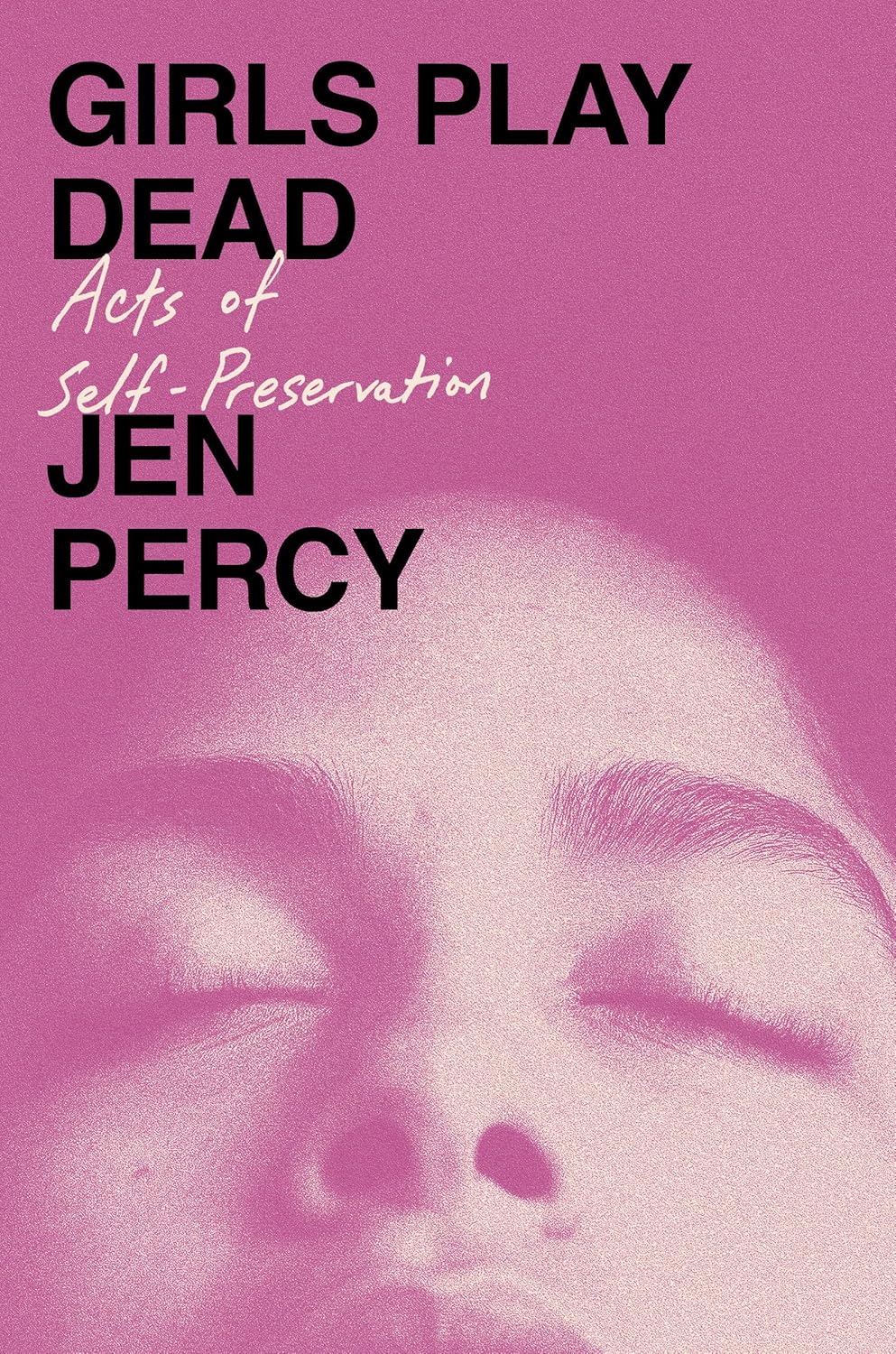

These sorts of questions inspire, animate, and confound the award-winning journalist Jen Percy’s second book. A dangerously neat title-subtitle combination, completing the argument that the book will make, Girls Play Dead: Acts of Self-Preservation follows from the premise that in moments of terror, bodies and minds are hardwired to defend themselves through reactions like immobilization or dissociation. These adaptive behaviors make evolutionary sense: prey who feign death during an attack on the savanna can disinterest predators who know not to consume dead, potentially bacteria-ridden meat. But for humans, playing dead or freezing can be less reliably effective. Dissociation is useful internally, as a short-term barricade against acute overwhelm, but Percy examines these phenomena as they play out in a social realm rife with manipulations, misread cues, and misogynistic assumptions.

In an early resonant passage, Percy writes: “There were times that I knew that I was in trouble, or I felt uncomfortable, or I didn’t want to do whatever behavior was being suggested next. But I did. I went along with it, or I didn’t say no, or I didn’t leave, or I didn’t want to be rude, or I thought I was overreacting, I didn’t want to hurt his feelings or I thought it wasn’t that bad, or I thought he didn’t really mean it.” Having found herself in these situations, vexed by how they came to pass, she later concludes: “I spent years living in the world not understanding the behaviors that rose up suddenly during or after fear. What did fear even look like? How do you tell stories about it?” Percy wrote this book to map out what fear does to a person and to tell stories about it—the fear that precedes a traumatic event, and the fearful imprint such an event leaves on the nervous system. Girls Play Dead is a documentation of the casual and caustic ways women can be betrayed by men, as well as an attempt to demystify and redeem the ways women can react, which often feel like failures, even self-betrayals.

PERCY’S FIRST BOOK, Demon Camp: A Soldier’s Exorcism, was a deeply reported work about the shape-shifting nature of post-traumatic stress disorder, told through the life of an Afghanistan war veteran named Caleb Daniels. Following the deaths of multiple men in his unit, including his best friend, Daniels becomes haunted Stateside by “the Black Thing.” Voices, apparitions, uncanny coincidences. After trying to cleanse himself in sweat-lodge ceremonies with a Lakota man and a prayer-based counseling ministry known as Theophostics, he receives an exorcism at the hands of a Baptist preacher. Enlightened, if not fully cured, and now married to the preacher’s daughter, Daniels starts to lead war-ravaged service members and troubled civilians to the shambolic retreat center in Georgia to have their own evil spirits banished. Demon Camp is strange and engrossing.

In a direct statement unusual for her book, Percy writes: “I wanted to talk to veterans and the families of veterans for the same reason that many were telling me I could not talk to them. That as soon as we say words like PTSD and trauma we have permission to ignore the problem because we think we understand it. It wasn’t so much that the familiar narratives weren’t working, it was there appeared to be no narrative at all.” Percy and her subjects share a skepticism about PTSD as a diagnosis, its failure to appreciate or contend with what’s really happening, and a respect for the various forms of madness it can assume. When asked by Vogue upon Demon Camp’s publication what drew her to this story, Percy replied, “I’m interested in aftermath, or what follows disaster—the ruins—and how one survives forever haunted by it.” Over the past ten years, Percy has emerged as a dogged chronicler of aftermath. A frequent contributor to Harper’s and The New York Times Magazine, she has written features on the mental-health crisis among Iraqis hounded by the Islamic State, an army interrogator who worked at Abu Ghraib, and two Japanese men searching for their loved ones in the wake of the 2011 tsunami, for which she received a National Magazine Award.

While Percy’s early-career reporting on America’s disastrous foreign interventions led her to examine PTSD in Demon Camp, her time as a girl and young woman inspired her to scrutinize, even more closely, the body’s responses to danger and damage in Girls Play Dead.The two books form an impressive diptych of trauma—the first mainly depicting men’s, the second, women’s—but they differ vastly in their styles.

Demon Camp is tightly focused on a core cast of characters, Daniels and those around him. Percy is present in the narrative, but she withholds much about herself. “I don’t have trauma like your trauma,” she tells Daniels, without elaboration, to which he replies, “Your trauma is just as important as my trauma.” She undergoes an exorcism and its description is visceral, but very brief. Girls Play Dead begins with a two-sentence paragraph: “There is no single anecdote. What I’m talking about is an accumulation.” Her amassing includes the man she saw smothering his crotch in public, the gynecologist who tells her to keep her motorcycle boots on, the Spaniard who won’t take no for an answer. Percy quotes from a page of Helen Garner’s nonfiction she once “earmarked” and “never forgot,” as well as a lawyer who tells her that most assaults don’t begin with the use of force. Percy’s own experiences are the establishing shot for the book, and she returns to them in jump cuts throughout many other women’s stories.

The change in Percy’s storytelling may owe something to changing times. In a long tradition of immersive works of journalism, Demon Camp was published in 2014, the same year as Anand Gopal’s No Good Man Among the Living, Anand Giridharadas’s The True American,and Beth Macy’s Factory Man. It wasn’t obvious at the time, but 2014 was something of a twenty-first-century zenith for this kind of nonfiction. With notable exceptions—Rachel Louise Snyder’s No Visible Bruises comes to mind—there’s been a slow, steady shift away from the publication of so many richly reported books by journalists that focus on little-known or anonymous subjects, taking readers deep into their worlds (a Virginia furniture-manufacturing plant, an Afghan village) and revealing how the forces of history pulse through their lives. Where one thing ebbs, another flows. That same year saw the publication of three indie hits that would help take mainstream a new current of writing: Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams, EulaBiss’s On Immunity, and Helen Macdonald’s H Is for Hawk.

These books signaled that so-called hybrid nonfiction was a force in publishing. The loose term is generally understood as a three-part cocktail, blending memoir, reportage/research, and cultural/social commentary. Levels of each vary, but personal narrative is usually the base or through line, with resulting varieties of memoir running the gamut from “lyrical” to “reported.” (Two additional industry designations it pains me to relate: “outward-facing memoir” and “memoir plus.”) The likes of Maggie Nelson or Olivia Laing may have played on the borders of existing genres, but the child of their mixed modes is now a familiar genre unto itself. One reason it’s become so popular, in our age of diminished attention spans, within a balkanized media system that necessitates news-hook relevance to attract publicity for fiction and nonfiction alike, is that books in this multi-hyphenate category are seen as marketable to several audiences at once. It’s not just a life story, straightforward reportage, or mere criticism; it’s all three combined—and therefore an examination, an intervention, a reckoning.

As Meghan O’Rourke, author of the hybrid The Invisible Kingdom, pointed out in Bookforum’s previous issue, the publishing-landscape shift means that noncelebrity memoirists now write of their lives through the prism of “a single ordeal or theme—grief, illness, recurrent pregnancy loss.” Divorce, too. Over the past year, Lyz Lenz’s This American Ex-Wife and Haley Mlotek’s No Fault wove the stories of the authors’ own separations with statistics, film and cultural criticism, and interviews/conversations with friends. But what gets less attention is how this ascendant form has changed the way many journalists and scholars write as well, either drawn or pushed into it. Hard science or reporting can be softened by interweaving a personal story so that readers feel an intimate connection to the expert or reporter, a more vulnerable Virgil to the reader’s Dante.

There’s nothing wrong with this per se. On the subjects of gendered violence, injustice, and poverty, the journalist Sarah Smarsh’s Heartland and public-health executive Michelle Bowdler’s Is Rape a Crime? are both excellent. But hybrid nonfiction carries more risks for practitioners than its increasing ubiquity might suggest. A journalist must turn herself into a character who develops; a memoirist must leave the house and interview people; and both need to shape, build, and sustain an original argument. With those three wellsprings to draw from, the balance between depth and breadth grows more elusive. You must not only master each craft but also blend them seamlessly.

HAVING SET DOWN HER BOOK’S THEMES IN THE OPENING CHAPTER, Percy writes about growing up in rural Oregon and learning wilderness survival: “In the summer, my mother and I practiced playing dead in the woods.” These scenes are fascinating. So too the relationships between Percy, her mother, and her grandmother. Nana had abandoned Percy’s mother to join a millenarian cult led by the New Age guru Elizabeth Prophet and driven off to live on the edge of Yellowstone National Park. The bunkers were twenty feet deep. When the world didn’t end on March 15, 1990, Nana returned. “I can’t believe we’re related!” her mother tells Percy. “If I ever end up like Nana, kill me!” Yet Percy’s mother holds her own spiritual beliefs—past lives, ghosts, premonitions—and, like her mother before her, and her daughter after, she was violently mistreated by men.

In a chilling passage, Percy’s mother, working her first job out of college in the Forest Service, is asked by her boss to survey trees on a scree. She knows it’s dangerous, but since she’s already almost been fired for “being distracting” as a woman, she proceeds. The loose rocks give way. She tumbles head over heels several hundred feet, landing at the bottom severely injured. When Percy tries “to remember the first time I gave up my power, my first submission,” she recalls that in fifth grade, her mother handed her the landline, saying it was for her. “It’s Sean, baby,” the man says, referring to her as Jenny. Percy knew no Seans. Mirroring the man throughout the bizarre conversation, matching his I love you at the end, she spends that evening thinking about what he looks like. On the second or third time he calls, Sean says, “I want to fill you with my cum until there’s nothing left of you.” Without knowing what he means, Percy replies, “I can’t be all cum” and hangs up in defiance. She never tells her mother what happened.

But it’s not always men. Percy recalls feeling that the first time “the boundaries of my body were being invaded” was by her fear of “inheriting Nana’s fanaticism,” the hugs she wanted to wriggle away from. I get it. My father’s mother, who we also called Nana, directly invaded my boundaries, saying afterward, “Now, you must never do that to yourself!” That’s probably why I didn’t tell anyone about the man in the Holyoke Mall: I’d learned long before to keep secrets, to understand that any untoward event would be my fault, that I was marked, that I was bad. My Nana was herself a guru, the still point of a turning wheel of spiritual seekers, whose placid faces, as they beamed like moons in our secluded house where she led satsang, haunted me for years. That is, until I saw the same expressions on the orange-clad and Uzi-wielding Rajneeshees in Wild Wild Country.

Percy’s matrilineal memories, intense and shocking, arrest our attention again and again, but they are often isolated, with ample white space setting them off from the text before or after. This enhances the immediate effect, a cliffhanger or kicker at the end of every section. Yet the tactic comes to feel too polished in its effort to convey discontinuity, and the resulting ambiguity itself risks undermining the reportage and analysis that forms the core of the book. Like still frames when we may want to see pictures in motion, even accompanied by voice-over, these scenes feel as though they’ve been put to work as exquisite compositions rather than fully worked through, creating a significance that gathers force. Percy’s relationships with her mother and grandmother, and theirs to each other, are clearly central to Percy’s self-conception, and to the development of her interest in the subject at hand. Yet there’s something fuzzy about what exactly Percy is telling us, especially in regard to how these dynamics between women and generations apply to the later stories in Girls Play Dead, which invariably center on male aggression.

In one short offset section, between a troubling memory of her father demonstrating his 9 mm’s laser sight by aiming at Percy’s forehead—it’s unloaded, her mother assures her—and a story of a high school party when she thought her date was crawling into a bed with her but it turned out to be a drunk stranger, she writes:

“My mother was born into this,” I told a friend.

“But so were you,” she said. “Weren’t you also born into this?”

The dialogue feels true, and deep, but would this elliptical passage be so haunting if the meaning didn’t remain somewhat vague? Whendid this chat occur, and what exactly are they referring to? Is “this”a life of guns and homemaking, of violent patriarchy, of intergenerational trauma? It could well be all three; if so, what does Percy actually make of her inheritance?

Midway through the book, she relates how she suffered from chronic pain that a massage therapist or healer helped alleviate; Percy finally realizes: “The pain was in the same location on my body as my mother’s. The same patch of flesh she bruised on impact. A memory in the shape of my mother.” End of section. Wait, what? It’s not that I doubt this: just the opposite, having had my own embodied memories that convulsed me in the manner of a demonic possession. But I yearn for her knotted point here to be, like those muscles that hold my trauma, kneaded more firmly and extensively so that there’s release, integration.

“My mother thought she could keep me safe from bears,” Percy writes at one point, returning to her early playing-dead lessons under the ponderosas, “which would translate to keeping me safe from men.” There’s simply more to be said about this incredibly complex relationship. Her mother played the bear.

Percy’s use of so many stained-glass panels of experience exemplifies a tendency in the book toward refracting an atmosphere and away from adducing a larger meaning from the material, leaving a surfeit of negative capability. It becomes apparent, as Girls Play Dead moves from Percy’s own story to her extensive reporting, that her fragmentary, lyrical approach can feel ill-suited to illuminating subjects outside the self.

THE EXTENT AND VARIETY OF PERCY’S REPORTING in Girls Play Dead is significant. Locating so many women, earning their trust, interviewing them repeatedly, and composing their stories is, on a practical and psychological level, a journalistic feat. Most of the book’s chapters are molded around different ways women respond to fear, the reportage interwoven with literature, research, and interviews with experts—and occasionally rethreaded with Percy’s own life. In a chapter on how the body can completely shut down in the wake of trauma, there’s Kim Corban, who was raped as a sophomore in college. A year later she began to suffer from horrific seizures that doctors diagnosed as PTSD-related. In a chapter on agoraphobia, defined by its nineteenth-century neologist as “a fear of fear” and by a present-day “feminist geographer” as an extreme breach experienced in the “boundaries of the embodied self,” we meet Sarah, a twenty-six-year-old sex worker who was trafficked as a minor. Now, she is compelled to employ a neighbor to retrieve her mail and take out her trash. One of the last chapters features three women incarcerated for murdering their longtime abusers. Through a 2017 Illinois law allowing new context to be taken into account for resentencing, a lawyer Percy profiles spends years assembling their petitions. One gets three years knocked off her sentence, down to twenty-seven. “The women were led to believe their stories had power, and they were given the promise of that power, and now what?” Percy asks. “What else was there? I couldn’t think of anything myself.”

The book’s thematic core is a chapter called “The Frozen Ones.” Here, we meet Lee, who was nineteen when she was raped one night during a military exercise. A literal warrior-in-training, she sums it up: “everyone imagines how they would react, and I had always imagined I would fight and get away.” But instead, Lee tells Percy, “I just froze.” When Lee’s friends found out what happened to her, they were “appalled and confused. You didn’t do anything? You didn’t say anything? You froze?” With any luck, this book will once and for all put an end to that string of questions, the appalling confusion.

What seized Lee and so many of us, Percy explains, is called tonic immobility. An ancient part of the brain, the amygdala, suspends the flight-or-fight response—seemingly in a last-ditch effort to deter perceived mortal threat posed by a predator—affecting sensory-motor capabilities, as well as the reasoning functions housed in the prefrontal cortex. Jim Hopper, a clinical psychologist Percy interviews, has been writing about the phenomenon for years and calls this impaired deliberative condition “shocked freezing” or “no-good-choices freezing.” The involuntary response, effectively severing your brainstem from your spinal cord, can make you seem, to an overly interested or intoxicated party, passive or even silently acquiescent. But if you’re scared stiff and can’t heave words into your mouth, nothing is affirmed. Does the stare of a deer in headlights signal consent to being struck by a fast-moving car?

In unspooling Lee’s story over the course of “The Frozen Ones,” speaking with Hopper, reading Ovid’s Metamorphoses, looking at Ophelia as painted by John Millais, and telling her own story of near-immobilization via a date-rape drug while in the Canary Islands with a friend, Percy delivers a chapter whose parts cohere even though they are many. There’s focus and framing. The construction of other chapters is less sturdy. Sections are welded together with phrases like “And as it happens while thinking of this topic . . . ,” “The science tells us

. . . ,” or “And there’s more . . . ,” and the sheer multitude of materials she uses can render the structure unsound.

In “Rapture,” she writes about trauma-induced delusions, including a case of dissociative identity disorder; her own hallucinations following a reporting trip to Syria; the unequal treatment we afford war and rape narratives (riffing on Tim O’Brien’s famous formulation, she writes, “But who has ever said, A true rape story that never happened”); the mind-warping experience of orgasming during rape; the ecstasy of Christian mystics and saints and how near-death experiences might relate to it; how women have historically transposed their stories of assault into tales of violated animals, who generally have elicited more concern from the public; and the chapter isn’t done yet. All this is fascinating, and it’s true that the Latin rapere (“to take or seize”)is also the root for rapt and rapture. But as with entries under a word in the Oxford English Dictionary, there is some drift in meaning from where we began.

Near the end of “Rapture,” in what served as the set piece for a 2023 story for The New York Times Magazine, Percy attends a workshop hosted by a retired police chief and a retired prosecutor at a policy academy in the Shenandoah Valley. The purpose: teach CIA agents, social workers, and members of special victims units how trauma can shatter someone’s ability to narrate in a linear fashion what happened last night, how that midnight fear could have been so paralyzing that she couldn’t even speak or scream, let alone fight back. The chief asks who “remembers how many times we judged a victim because we didn’t understand their behavior? Maybe they were texting their abuser the day after the assault and saying, ‘Hey, did you have a good time?’” The room nods. He says they’re not alone: “Now I teach my mistakes.” It’s a line that evokes his regret and shame, that makes us wonder what may have happened to the victim of such a mistake, and it suggests that, perhaps, there’s progress afoot.

The chief’s quote ends a section—it ended the magazine piece—but Percy goes beyond her original reporting, rifling through the two books that apparently represent the gold standard for police interrogation, The Investigator Anthology and A Field Guide to the Reid Technique:

The manuals state that “an assault that is reported immediately is more likely to be truthful” (not true—sexual assaults are rarely reported immediately) and that cops should “look for inconsistencies in the victim’s statement about the suspect and the assault,” because they were signs of deception (not true). It instructed police to watch out for “illogical behavior during the assault.” (Illogical behavior can be a normal response to trauma.) . . . “The victim who one minute is answering questions in total control and then breaks into a crying spell and wipes dry eyes with a tissue, and within a few seconds is able to return to the interview fully composed may be feigning distress.” (Changes in composure are normal.) “If you ask the victim, ‘Why do you think that man did this thing?’ a truthful victim will say he has to be sick or a pervert. The deceptive answer is ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I really haven’t thought about it.’” (Neither one of these responses relates to truth or deception.)

This parenthetical point-by-point refutation of what constitutes the basis for law enforcement’s understanding of sexual-assault victims is devastating. Even a jaded reader can’t help but be shocked by this codification of a veritable greatest hits of rape myths. And yet—we move on. The revelation burns, then goes dark. Why bury this at the end of a chapter and not unpack it further, whether through interviews or Percy’s own sense of anger or resignation? Why devote so little space to dismantling the instrument and emblem of how the titular acts of self-preservation are still so frequently judged—or, really, outright dismissed?

GIRLS PLAY DEAD CAN FEEL AT ONCE UNFINISHED AND OVERWROUGHT, a paradox that gives certain strands of hybrid nonfiction a queasy, unsettling quality. The genre promises to be greater than the sum of its parts, like that panel of stained glass. But the leaded cames that run between the colorful pieces, what truly holds the picture together, can’t be suggestive white space or asterisks or ——, it must be the sticky self and an epoxied argument together spread evenly out. If those elements are in short supply or aren’t mixed well, the fragments are not securely affixed to one another, and juxtaposition loses its force in the glare streaming through the gaps. It becomes hard to know what you’re really looking at.

Percy’s achievement in narrating these women’s remarkable acts of survival (hers included), which for too long have been misrepresented or discounted, is a lasting one, for which she should be celebrated. I have no doubt she will be. Many readers may not care much about some missing pieces or jagged edges; and the form itself can hide its cracks by celebrating them. Still, I return to beginnings, that descriptive title and subtitle, and the opening: “There is no single anecdote. What I’m talking about is an accumulation.” There is in the end something of a catalogue to Girls Play Dead: a headlining statement of consequential and overlooked fact and a series of case histories attesting to it. The book proceeds from reaction to reaction, psychologist to police chief, Ophelia to Ovid, shifting from essayistic collage to memoir to reportage, but it lacks the kind of momentum that comes from fully developing an argument or conveying the arc of a personal awakening.

In the last paragraphs of “Rapture,” Percy writes of healing from war-reporting trauma through eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), a therapeutic modality relying on bilateral stimulation to revisit painfully present memories and properly reshelve them in the past tense. “I saw everything in reverse,” Percy writes, “the blood returning to the body of the soldier killed in the field by the American boy who knew too little about his trigger.” A precise sentence that enacts what it describes, each preposition pulling us backward in a revelation of nouns, ending with a deadly spark of ignorance that sets everything in motion. She follows the memory to even more distant days: “The dragon guards the precious jewels, and the birds sing back to me. Christ steps off the crucifix. How far back could I go? As far back as my mother had gone to inhabit past lives to cope with the present?” She quotes Adrienne Rich on how “entering an old text from a new critical direction” is “an act of survival.” And when Percy’s friends see her after EMDR, they say, “You seem here.” To which Percy responds, in the final line of the chapter, “Well, if I’m here, then where had I been?” Here are the formidable skills at Percy’s disposal, on display throughout Girls Play Dead. And yet the very richness of the material often conceals how much could still be tapped, and her questions, while powerful in their posing, capture something within this book that remains unknown or unknowable.

Elias Altman is a partner at Massie McQuilkin & Altman Literary Agents.