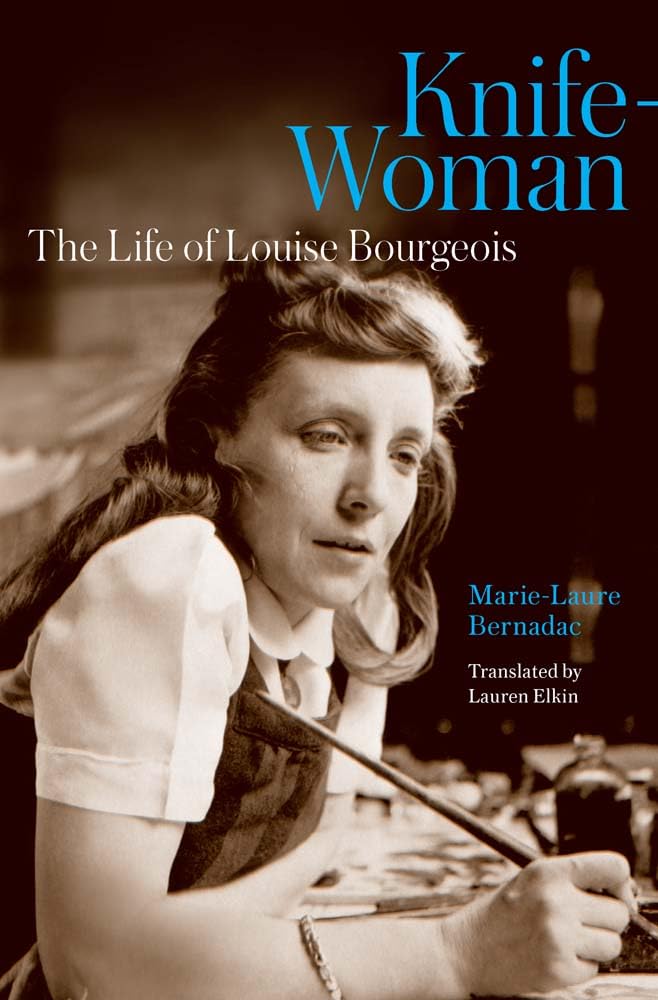

HOW CAN I NOT START WITH THE DICK PIC? Like many of its kind, its origin was practical: when Louise Bourgeois needed an updated portrait for the catalogue of her 1982 Museum of Modern Art retrospective, Robert Mapplethorpe shot his iconic photograph of the seventy-year-old artist wearing a monkey-fur coat and clutching her phallic sculpture Fillette like a baguette. “Intimidated by the session with Robert Mapplethorpe, who was famous for his overtly sexual work, she went armed with a defensive weapon: a phallus,” Marie-Laure Bernadac writes in her new biography, Knife-Woman: The Life of Louise Bourgeois, first published in France in 2019. While it’s difficult to imagine Bourgeois intimidated by anyone, it’s telling that her defense would be her art itself. She titled the two-foot plaster and latex sculpture Little Girl, its oscillation between male and female, penis and torso, humor and violence, a way to reclaim power across history and family. In the end, the image that appeared in the catalogue cropped out the joke by zooming in; we see only Bourgeois, face crinkled in a grin, eyes twinkling.

The most difficult biographical subjects are not those with scant archives but those who’ve made their life their life’s work. How do you write about an artist whose story is threaded through seventy-five years of objects; who wrote incessantly in her diary starting at age eleven; who’s already been the subject of several documentaries, a New Yorker profile, and major museum retrospectives (including by Bernadac) with extensive catalogues and chronologies? (The curator Deborah Wye’s foundational scholarship feeds all subsequent takes.) What’s left to say about an artist whose complete interviews have been collected and published (by Bernadac herself); who saved a box of “psychoanalytic writings” from 1952 to 1966 that were published in 2012 as a way to “allow us to listen in on her thoughts, feelings, and dreams during this long period of depression and analysis,” and who “kept everything”? Bernadac’s book, then, arrives not as a revelation but as a distillation. Its biggest understatement is that “very few artists have gone so far in the precise duty of their psychic functions or the construction of their identity.” Bernadac is a deft—if sometimes deflecting—stage manager, knowing just when to bring certain details and artworks into view. She includes herself in the group of “all those who loved” Bourgeois; as a curator, her long association with the artist provides a specific intimacy. She’s handled many of these works and the artist herself and refers to her as “Louise” throughout. Yet even in death, the artist’s voice overshadows Bernadac’s: this was always going to be Bourgeois’s show.

Bourgeois’s life “cut right across the twentieth century.” (Here, the verb refers back to the book’s title: Bourgeois is a knife-woman, bushwacking through history. And hat tip to Lauren Elkin for her agile translation of Bernadac and Bourgeois.) Born in France in 1911, she died in 2010 in New York, where she had arrived just before World War II. The art-historical sprawl of the city this time span encompasses is mind-boggling: she hung out with Wifredo Lam in the 1940s and taught Keith Haring in the ’80s. The traditional structure of biography serves Bourgeois well, and Bernadac leans into it, since “the older Louise got, the farther back she traveled in time, venturing closer to her earliest childhood memories.” This offers an effective bookending: we’ve learned so much about her by the time we get to her most iconic works from the last two decades of her life—she only started making her gigantic spider sculptures and room-sized cell sculptures in the ’90s, when her prolific drawing and printmaking also took off—that their dredged adolescent references feel familiar. We also realize from her initial and firsthand exposure to art, her studies in France, her marriage and life in New York, and her work itself that it cannot be fully true, as Bernadac claims, that “she was more interested in the subjective and unconscious interior processes by which artists create than in the form and history of art.” Why can’t it be both? Why is art history defined so narrowly and without feeling? After all, Bourgeois grew up in a culture where old tapestries were sold by art dealers and used as blankets on cows giving birth.

She was born on Christmas Day, a double disappointment: she was not a son (though still named after her father, Louis, a weighty inheritance), and the doctor told her mother, “You are ruining my festivity.” Bourgeois was a “little tomboy, climbed trees and wore her father’s short trousers.” Yet her parents also dressed her in the latest fashions from Chanel, Paul Poiret, Sonia Delaunay. She was the middle child—her sister, Henriette, was six years older; her brother, Pierre, just fifteen months younger.

Her father trained to be a landscape architect but ended up in his wife’s successful family business, restoring tapestries. Her mother, Josephine, was a weaver; Bourgeois recalled scores of workers washing tapestries in the Bièvre river that ran by the family’s estate in Antony, outside of Paris. (The river water was rich in tannin, which helped dye the fabrics.) Bourgeois was three when her father was called up to fight in World War I and injured; Josephine took her to visit him in the hospital, where she witnessed maimed soldiers returning from the front, as well as her father flirting with the nurses. “A ladies’ man,” he had an affair with her au pair when Louise was a child, and she labeled it the most profound wound in her life in a 1982 essay, “Child Abuse,” in Artforum, which outlined how she could never shake this betrayal. Decades later it would shape ambitious works like The Destruction of the Father (1974). But Bernadac’s book implies that her relationship with her mother and brother may have been the greater trauma. Josephine, whose health started to decline when Bourgeois was five, died fifteen years later. By then, Bourgeois was her mother’s primary caretaker. Bourgeois first attempted suicide shortly after: she jumped into the Bièvre.

A series of suitors followed, as well as a second suicide attempt. In 1934, she wrote a list in her diary of “rules to live by,” which Bernadac describes as “things to do to fight against depression: eat healthily, rise early in the morning, tidy up, beware of worldly and bourgeois people who are supposedly interested in art but who have no soul and only respect famous people.”

Bernadac doesn’t spell out Bourgeois’s turn to become an artist but gives us plenty of contributing factors. One, linked to the psychoanalytic dimension of her work, is Bourgeois’s professed need to understand “why we do what we do”—not just art, of course, but of course art, too. As a child she helped her parents complete tapestries for conservative clients, replacing sections of genitalia with leaves. She worked as a docent at the Louvre and entered the Sorbonne to be a mathematician. But soon she was apprenticing in ateliers across Paris, including Fernand Léger’s, where she looked after his American students with her English-language skills, fretting that to be an artist was “to be asocial, a ‘monster’ for other people, in search of an ideal.” Perhaps art could be an outlet, since she already knew that “my emotions are inappropriate to my size.”

In the family’s Old Tapestry Shop in Paris, Bourgeois “created her own little art gallery,” selling drawings, prints, posters, and occasionally paintings. It was there, in 1938, that she met art historian Robert Goldwater, with his “beautiful brown hair, a sporty hat, beautiful hands and light blue neckties,” who came in to admire a Picasso etching. Nineteen days later, “in between conversations about Surrealists and the latest trends, we got married.” Their marriage lasted thirty years, until Goldwater’s death, and in Bernadac’s sympathetic framing, it was the lighthouse to Bourgeois’s stormy seas. It also seems to have brought out the romantic in both of them. In a letter sent just before she left Paris to join him in New York, Bourgeois wrote, “I dreamt about you, we were running one after the other in a street full of skyscrapers.” Later, Goldwater wrote Bourgeois that she had affected how he saw art: “Whatever I write now (I mean really whatever art I see) is a combination of academic method, which is pretty poor in itself, + a large part of your esthetic vision.” While many other European artists of the time were fleeing fascism along similar routes, she traveled first class on the Cunard liner Aurania in the autumn of 1938, painting throughout the two-week voyage.

Goldwater’s family was wealthy and connected; his father was the New York City health commissioner. Goldwater was a celebrated scholar of African art in an era when it was still primarily studied by anthropologists, and modern art in an era when it was considered too new to be understood. He introduced Bourgeois to a robust cultural scene in New York. She met exiled writers and artists from around the world; she curated an exhibition with Marcel Duchamp for the Free French war effort. She posed for Berenice Abbott. She enrolled in the Art Students League and continued to draw and paint. She started adoption proceedings for a French child in 1939, then got pregnant; with the birth of her third son, fifteen months after her second, she suddenly had Michel, Jean-Louis, and Alain. She called them her “wild beasts.” Her diaries from the early days in New York are a blur of gatherings with prominent figures like Lionel Trilling, John Rewald, Clement Greenberg, and Pierre Matisse, alongside notes about a sick child’s temperature. News to me was her “unrequited love affair” with Alfred H. Barr Jr., then director of MoMA. She was at the heart of the art world, even if her work remained in the shadows.

Bourgeois got a studio of her own in August 1941, when she was able to work outdoors on the roof of the family’s 142 East Eighteenth Street apartment building, and in the Easton, Connecticut, country house that she and Goldwater bought. She started to experiment with sculpture. What prompted this shift remains mysterious, though we know Léger encouraged her to consider it. Bernadac suggests that how a carved sculpture often comes into being (by paring down a material with the force of sharp tools) opened deeper wells of reference and physical outlets for her attacks of anxiety, rage, and aggression. Bourgeois also must have been propelled by having more space, by sculpture’s physical challenge, by the relative dearth of women sculptors in Western art history, and by the work that her husband studied and that she was seeing around town. She later said that she became a sculptor because “it allowed me to express what I was embarrassed to express before.” Some of her first pieces were made from cedar planks left over from the construction of water towers on the roof of her building. She dug into the wood with a razor blade and reassembled it. These actions, Bernadac writes, “allowed her to release her aggression and violence.” We don’t discover how she acquired her tools or learned or adapted sculpting techniques. We do, however, get the incredible description by her friend, the curator Arthur Drexler, of entering her studio in the late ’40s: “There stood this very small, intense woman—extremely svelte, handsome—wielding a huge cleaver with which she worked on balsa wood. Time and conventional notions of reality were annihilated. She was alarming as she attacked with wood.” Her painting Roof Song (1946–48), though unmentioned by Bernadac, captures the joyful release of this time, too: she depicts herself towering over a brick building’s roof, long hair flowing behind her, a huge grin on her face, as one of her totemic sculptures stands guard.

Back at the family estate at Antony in Occupied France, her brother cut down all the property’s trees—an action that haunted Bourgeois’s later work—and suffered a series of breakdowns. Suitcases already packed, Pierre tried to join Bourgeois in New York in 1945, but she “asked her father to prevent him from coming, concerned that his presence would ruin her marriage.” Pierre was instead institutionalized by his father. He implored his sister to make a written request to let him out; she did not. He spent the rest of his life in a psychiatric hospital. She only visited him once again, in 1957, instead sending the subletter of her Paris studio, the American artist Shirley Jaffe, to deliver things to him. Pierre continued to write her heartbreaking letters: “My dear Louison . . . Jaffe brought me a pomegranate which I ripened beside your photograph.” He died there, in 1960, in his sleep. She may have kept her distance because she was afraid of being institutionalized herself: “Fret or worry no 1 I have Pierre’s trouble and will fall apart slowly and surely.”

In 1948, her father came to visit her family in New York for the first time, a reunion that was overshadowed by a 4 am incident in a nightclub in which he performatively chose a prostitute in front of her. Louis died suddenly in 1951, and Bourgeois wrote that “losing my father—it is as if I was castrated I lose everything even my equilibrium.” She fell into an extreme depression. In January 1952, she began analysis with Dr. Henry Lowenfeld, “a fairly unorthodox Freudian” who’d published on psychic trauma and creativity. Bourgeois didn’t make much work between 1953 and 1960, but Bernadac sees this period as “a critical turning point.” Bourgeois’s art became tethered to her psychoanalysis, and a new kind of sculpture emerged. “Leaving behind the rigidity of wood,” she turned to “more supple and liquid material such as plaster and latex,” substances unsettling in their allusion to skin and the body. She embraced the Sisyphean task of analysis. An ideal patient, she wrote of the compulsion that drove her creativity: “Never let me be free from this burden that will never let me be free.”

This was also a period in which the lifelong diarist discovered, through analysis, a new form of writing that served as a companion to her art, something that could help give it shape and meaning. Bourgeois treated “compulsive” writing as “a form of exorcism.” (Her art is also described elsewhere in the book as “a form of exorcism.”) Analysis helped distill specific metaphors that dominated the writing and forms coming out of her: the woman as house (and housewife); the giant spider (who, though something out of a nightmare, represents the protective mother); and the spiral, which summed “the anxiety void.” These narratives could be almost too neat, as Bernadac argues, becoming “an echo chamber for the Freudian model.” Bourgeois created artist’s books with gnomic fables. (Often these are beautiful and haunting; occasionally they veer into pretention.) Bourgeois’s ego drama is always tempered by relatable ambitions: “I want to be pretty, nice, popular, have friends for dinner, be successful as a sculptor, push myself like everyone else, but above everything else, be liked,” she wrote in her diary in 1966.

Bourgeois’s turn to softer, more sensual materials coincided with her participation in Lucy Lippard’s important “Eccentric Abstraction” show in 1966 as the oldest artist. (Like Agnes Martin, included in “10,” the show of Minimalist painting and sculpture that same year, Bourgeois appeared both as godmother and bellwether of a new abstraction.) Two years later she made Fillette, a nod to the psychoanalytic concept of the part object, in which an infant’s first understanding of the world, including people, comes from splitting it into objects that are coded as good or bad depending on what the child receives from them. Bourgeois had considered studying child psychology in the early ’60s, and in her analysis texts from the same period, she wrote of the “merry-go-round” of psychoanalyst Melanie Klein’s object relations theory. Bourgeois’s sculpture is both the “little girl” whose perception and personality are still developing, and the part object of a father: “When I hold a little phallus like that in my arms, well, I find it is a very sweet object, certainly not one I would ever harm.” Bernadac shirks any new explication; she quotes art historian Rosalind Krauss’s important writing on the topic, and name-checks Klein and fellow psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott. Yet Bourgeois’s own deep investment in psychoanalysis while making this work, and its obvious connection to it, obfuscates broader historical traumas as well: she made Fillette some twenty years after the Enola Gay dropped a similar-shaped bomb, code-named “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima. Like other great modern sculptors such as Constantin Brancusi, Alberto Giacometti, Barbara Chase-Riboud, and Eva Hesse, Bourgeois found the innate presence of a form lodged deep in the material and made it her own. She defined this discovery as disciplined loss: “Style is made like a statue that you hack away at—and it’s made by all the things you have given up.” And because she never shied from extremes, she took the part object to its ultimate embodiment: “the realm of the maternal,” in which the baby, once a part of the mother, is given up through birth, and in turn searches for that elusive whole.

Goldwater died suddenly of a heart attack in 1973; Bourgeois was in a self-described “state of shock” for a year, echoing her reaction to her father’s death. Her husband had kept the household together when Bourgeois was working and traveling, even as he was also busy with his own ambitious career. In many ways, her marriage is a refreshing reversal of the all-too-common story of the quiet wife in the shadows supporting her husband’s genius. And yet, it’s also true that her most prolific period and her greatest success came after his death and after her children were out of the house.

Bourgeois began teaching at the School of Visual Arts and met the artist Jerry Gorovoy, who would become her studio assistant and confidant for the rest of her life. Bernadac rushes through whole decades, like the ’80s, when Bourgeois, in her seventies, was happily hanging out in a New York City “underground scene which centered on drugs, performance art, psychoanalysis, and structuralism.” (Bernadac tends to summarize rather than analyze. She knows the vast material so well and has an eye and ear for pulling out the best stuff, but there were many passages where I was left waiting for her own take.) In her final decades, Bourgeois received younger artists in weekly salons at her brownstone like a “high priestess.” As the writer Joan Acocella described after attending one such gathering, “Bourgeois is not a dear old lady.” Or, as writer and critic Gary Indiana characterized his friend, “Her observations cut through the grease of small talk.” Into her late nineties, she kept pushing. One of her final projects, published the year she died, was a collaboration with Indiana, a “meditation on the physical confrontation of the man with his erection and the woman with swollen breasts and belly.”

There are a lot of swollen bellies in Bourgeois’s work. As Bernadac writes, “Few artists have represented childbirth so often or so explicitly.” Unfortunately, the author also takes this as an opening to rate Bourgeois’s maternal instincts; as early as the introduction, we learn that the artist “was a good mother and also a bad one, but a mother nevertheless.” And later Bernadac writes, “Some have called Louise a bad mother,” though no one is cited.

The maternal and the creative were not such separate labors for Bourgeois, and therefore always in jealous conflict. She wrote of her “bottomless sadness of days without work.” Being a mother was hard work, and yet it was defined as the state of “not working,” in that it kept her from her art. Encouraged by Goldwater in the ’50s, when she was too depressed to make much art, she opened a print shop like the one they’d met in, though it lasted just a few years. Her motivations were just to have a respectable “job” other than mother or artist to get out of the house: “if you have ‘a job’ you leave in the morning you come home at night . . . people respect you, you do what men do—” But if you aren’t able to find the time to make art, “you reduce to the size of an insect. Your energy turns into hate. When you work you could run in joy carrying the house on your shoulders.” Her metaphors directly reference two of her oeuvre’s best-known forms: the spider (even if technically an arachnid) and the Femme Maison, or Woman House.

She was embraced by feminists and participated in a series of exhibitions and events in the ’70s and ’80s, though, in typical Bourgeois fashion, maintained a certain ambivalence. “The feminists took me as a role model, as a mother. It bothers me. I am not interested in being a mother. I am still a girl trying to understand myself.” In fact, many of her late maternal images do not represent herself as the mother, but as the needy and helpless baby, a return to the psychoanalytic roots of her emerging imagery in the ’60s. As she wrote in a moment of frustration, “Am sick and tired of Freud and Co. It does not apply to any trouble I know. I do not want to understand. I want to be ‘cradled.’”

In the 1982 MoMA catalogue introduction, curator William Rubin called Bourgeois “a loner of another order.” The positioning stuck and isn’t adjusted here by Bernadac, though it feels, ironically, like a way of limiting her influence. Even if she loved to deny influence, it seems to me that Bourgeois was always positioning herself among rather than apart. She titled a 1955 huddle of pointed and rounded wooden forms One and Others. Which is the one? Which are the others? The stance underscores her unique place within art history and the identity that a woman is never without after becoming a mother. Bourgeois once explained that she could have used the title for many of her works.

My favorite work by Bourgeois was made on her roof in New York, far before her best-known latex, bronze, and marble sculptures, or her language-soaked drawings and prints. She called these totemic figures “personages,” undoubtedly influenced by conversations about and visits to see African art with Goldwater. They look strikingly modern and timeless: simple wooden pieces, minimally carved, sanded, and painted, sometimes with a plaster bulge to indicate pregnancy in an early nod to her signature theme. Human scaled, they can be arranged alone or together, erect on rough stone bases, growing directly out of the floor, or leaning against each other. We know they were made when “Louise was deeply frustrated,” Bernadac writes, “as a young artist and, moreover, the mother of three children, which is to say that in the decidedly macho environment of New York, she didn’t exist.” They were made when she first had room to carve out what she needed and first realized that her creation was predicated on a loss that demanded witness, company. They were made during and just after World War II, when she was separated from her father and siblings and refused to let her troubled brother come to her in the United States. They are singular. But they are most moving when seen in a group, their relationship to each other defined in the spaces between the art.

Prudence Peiffer is the author of The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever (Harper, 2023).