The Billy Lee Myth begins with a fact: he was once one of the most engaging young novelists in the country, greeted by some critics as the second coming of F. Scott Fitzgerald. “Brammer’s is a new and major talent, big in scope, big in its promise of even better things to come,” wrote A. C. Spectorsky, a former staffer at the New Yorker. “[His work] has impressive sweep . . . it makes many of today’s novels seem small, contrived, even mean.” Brammer earned the $2,400 Houghton Mifflin Fellowship a year after Philip Roth won it for Goodbye, Columbus, and in 1961 he published a novel, The Gay Place, that David Halberstam, Willie Morris, and Gore Vidal, among others, considered a far more impressive achievement than Roth’s debut. The Gay Place was “the best novel about American politics in our time,” wrote Morris, and Halberstam called it “a classic . . . [a] stunning, original, intensely human novel inspired by Lyndon Johnson . . . It will be read a hundred years from now.”

Johnson, for whom Brammer had worked when Johnson led the US Senate, was the one reader the book should not have had, according to the myth, for he was said to be so upset by the comic portrait Brammer had framed of him that he froze Brammer out of the White House and killed the biography Brammer had planned to write about him, destroying his confidence, snuffing his brilliant talent.

That is phase one of the Billy Lee Myth. Phase two claims—again, with some roots in fact—that psychedelia wouldn’t have exploded in the American 1960s without Brammer’s influence. This part of the story says the San Francisco hippie scene evolved out of a group of Texans transplanted from Austin, among them Brammer’s pals Chet Helms and Janis Joplin. Since Brammer, fresh from consorting with Ken Kesey, was singlehandedly responsible for turning Austin, Texas, on to LSD, the Summer of Love wouldn’t have occurred without him.

In sifting facts from the myth, it is instructive to return to the basement of the Dallas Municipal Building at just after 11:21 a.m. on Sunday, November 24, 1963. Whether or not Billy Lee Brammer actually stood on the spot as NBC news reporter Tom Pettit shouted at the cameras, “He’s been shot,” in a broadcast carried live across the nation, “Lee Oswald has been shot . . . Pandemonium has broken out,” and American history took a murky turn from which it has never completely recovered, Brammer stood at the center of the events. He had known John F. Kennedy; they shared a mistress. He knew the man who had just been sworn in as the new president. For years, he had endured Lyndon Johnson’s rages, and he had enjoyed the man’s difficult friendship. He knew Jack Ruby. In the days leading up to the Kennedy and Oswald assassinations, Brammer had stayed in the Dallas apartment of a friend who was dating a mobbed-up stripper from Ruby’s club. On Friday afternoon, when Oswald fled the

Texas School Book Depository after allegedly shooting Kennedy, he briefly returned to the house where he boarded, less than three miles from Brammer’s parents’ house in Oak Cliff, an area of Dallas that Brammer knew had always been a way station for the disaffected and the lonely. He had known dozens of Lee Oswalds growing up in that damned “jicky” place—“jicky” is what they had called it, meaning crazy-sad—and he could have told the interrogators a thing or two when Oswald wasn’t talking.

“Billy Lee was always ahead of the game . . . He was cuing the rest of us what to expect,” said Gary Cartwright, Brammer’s friend and colleague at Texas Monthly magazine. In a vastly unsettled period, Brammer’s gaze encompassed the whole horizon. He observed, more knowingly than anyone before him, Lyndon Johnson, who was “as personally responsible for American history since 1950 as any other man of his time,” in the opinion of Ronnie Dugger, author of the LBJ biography Brammer might have written. And then “when the culture came a’callin’, he was ready,” said Brammer’s younger daughter, Shelby. Brammer would become as important to certain segments of the sixties counterculture “as Ginsberg was to the Beats,” said Kaye Northcott, a former editor of the Texas Observer. “They were both mentors, teaching the impatient how to cope with our imperfect world.”

In 1960, as Houghton Mifflin was preparing Brammer’s book for publication, one of his editors, Dorothy de Santillana, wrote him to say that “B. L. Brammer” would appear on the cover (eventually, the publisher settled on “William Brammer”). “No one, I repeat no one up here [in Boston] thinks ‘Billy Lee’ is possible,” de Santillana said. “With all respect to your parents who gave it to you with such evident love (it is a very ‘loving’ name) it has not the strength and authority for a novel which commands respect at the top of its voice.”

The names Kennedy, Oswald, and Ruby naturally occur to many of us when we think now of what was possible and what was lost in the last third of the American twentieth century. When we watch an old film clip of John Kennedy’s acceptance speech at the 1960 Democratic National Convention, at which Brammer was present, drumming up delegates for Johnson; when we hear Kennedy’s words, “We stand today on the edge of a New Frontier—the frontier of the 1960s, the frontier of unknown opportunities and perils, the frontier of unfilled hopes and unfilled threats,” we think of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, of LBJ (“How many kids did you kill today?”), of Robert Kennedy, Ho Chi Minh, Richard Nixon. Of Harper Lee and Gloria Steinem. Abbie Hoffman, John Lennon, Bob Dylan. Many others.

The new frontiers that opened up in the United States in the 1960s were personal as much as political—a familiar truism these days. Countless moments arose or were improvised for freedom from traditional restrictions and for destructive self-indulgences. From our vantage point, the real story of these new frontiers may be told most vividly now by studying the movements and companions of a hard-to-locate man with the improbable name Billy Lee.

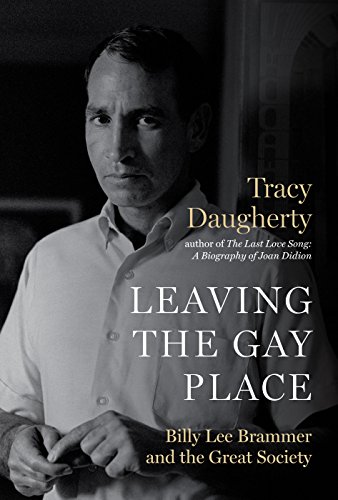

Excerpted from Leaving the Gay Place: Billy Lee Brammer and the Great Society by Tracy Daugherty. Copyright 2018 by Tracy Daugherty. Published in October by University of Texas Press. All rights reserved.