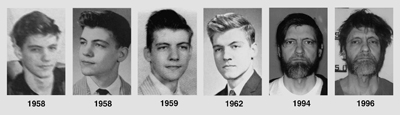

Opening with a deadly explosion and culminating in a tense FBI raid to capture a homegrown terrorist in the mountains of northern Idaho, Susan Choi’s third novel, A Person of Interest, can readily be called cinematic—specifically, it reads as a blueprint for a Hollywood thriller. It is, as they say in the trailers, “inspired by true events”: Choi has transmuted the case of the so-called Unabomber, Theodore Kaczynski, into the tale of the “Brain Bomber” and has kept close to the timeline and to many of the facts of Kaczynski’s story. Like Kaczynski, the Brain Bomber, abandoning a brilliantly promising career as a mathematician, targets scientists with his letter bombs. While his identity is still a mystery and he is holed up in a squalid western redoubt, he is catapulted to national celebrity after killing a highly regarded young professor. The Kaczynski affair is recent enough that readers will instantly recognize its more conspicuous facets duplicated in A Person of Interest—such as the publication of a long antitechnology screed in the New York Times at the bomber’s behest—but, in the wake of 9/11 and the refocusing on terrorism by the government and the media as primarily a foreign threat, we also come to this not-so-distant episode from a detached vantage. The peculiar climate of the mid-’90s, when for many the Unabomber was a subject as much of fascination (and even levity) as of fear or condemnation, is well behind us.

The material is auspicious for Choi, who retold the saga of Patty Hearst in her previous novel, American Woman (2003). That book was part of a resurgence of interest in Hearst in particular—Robert Stone’s documentary Guerrilla: The Taking of Patty Hearst (2004) was followed the next year by Christopher Sorrentino’s Trance, like Choi’s novel a fictionalized treatment of the SLA’s abduction and conversion of the heiress—and in days-of-rage radicalism more generally. Various Weather Underground memoirs were joined by novels such as Dana Spiotta’s wickedly incisive Eat the Document (2006), a book that brilliantly weaves together stories of ’70s political fugitives with those of their ideological progeny in ’90s Seattle. Choi’s novel stood out from these other treatments of bygone extremism by adopting a somber, at times brooding tone and by regarding her on-the-lam characters not primarily as political actors but as subjects for psychological scrutiny.

There are, however, moments of genuine insight into waning ’70s radicalism in American Woman. The novel provides a palpable sense of a movement adrift, whose justifications of violent action, in the final days of the Vietnam War, sound increasingly shrill and ethically bankrupt, even to many of its sympathizers. And more subtly, a kind of politics is embodied by Choi’s opting to focus not on the Hearst figure (named Pauline) but on the steadily more disillusioned radical Jenny Shimada, the “American woman” of the title. At the end of the novel, Jenny reflects that Pauline, after her arrest, would merely be “made more interesting by her adventure, a reinforcer, in the end, of the privilege she’d once seemed to spurn. . . . Their time together would be further obscured, or rather, never inscribed into the record at all.” Implied here—in Choi’s acknowledgment that our sense of public events, as they assume the contours of popular consensus, is shaped as much by distortions and erasures as by the facts—is a credo for taking familiar real-world spectacles and submitting them to the imaginative revision afforded by fiction, so as to restore what’s been buried, lost, or left out.

Choi takes a similarly sidelong, but far less satisfying, approach to the Unabomber case in A Person of Interest. She chooses to concentrate not on the reclusive Kaczynski figure but on one of his distant acquaintances, an aging, unhappy math professor identified only as Lee, who happens to be sitting idly in his office when the bomber’s latest package detonates in a room next door, fatally wounding a popular teacher named Hendley. Soon afterward, Lee receives an illegibly signed letter from a former colleague whom he has not heard from since the late ’60s, who, having seen Lee’s name in media accounts of the attack, now offers to “revive faded fellowship.” The quick-succession shocks of the bombing, the letter (which he presumes is mocking him), his questioning by the FBI, and his sudden ostracism by his suburban neighbors, as well as by his colleagues and students at the university, expose him to danger and, more important for Choi’s purposes, disturb his rigid, if superficial, sense of himself.

Before the bombing, Lee was muddling through a diminished and ever-shrinking “invisible life,” largely defined by his exile from an unnamed Asian country, riven by civil war, as a young man in the ’50s. Although Choi leaves vague much of his background, she stresses that Lee, having grown up a child of privilege, feels himself a “fallen aristocrat” in the threadbare life he has created for himself in the United States. Playing up the shabbiness of Lee’s existence—although becoming a tenured professor is hardly the worst fate to befall a refugee—Choi hints that the emptiness of his later years is a consequence of his having severed himself from the past. After Lee is questioned by two men from the FBI about possible links to the Chinese Communists, Choi writes:

Only one thing remained beyond doubt: Lee really had closed the door not just on native country and language and culture but on kin, all of them, said good-bye to all that and stepped over a threshold of ocean to never look back. There had never been a divided allegiance, a pang of nostalgia, not even a yen for the food, so that only months into his life in the States, when faced by two FBI agents in an American bus station, he could almost have laughed—not to be thought Chinese but anything whatsoever, apart from American.

There’s too much of this kind of intrusive analysis in A Person of Interest. Choi writes ploddingly, and at too great length, about her characters in the abstract; the effect is like reading an outline rather than a novel. And, one might ask, is Lee’s seemingly effortless sloughing off of his origins really credible, particularly so soon after his arrival? It’s conceivable that the dislocations of exile might not result in a “divided allegiance,” but it’s hardly plausible that a recent immigrant could banish his psychic links to his native country at will and assume that he’d be thought American in his new home—particularly an Asian man adjusting to life in the Midwest at the height of the cold war.

Through flashbacks, Choi spends a good deal of the novel recounting and commenting on Lee’s failed marriage (the first of two), decades before, to the headstrong Aileen, a relationship that began while she was married to Lee’s sole friend in his grad school days, a devout Christian named Lewis Gaither. The affair is briefly interrupted when Aileen discovers she is pregnant with Gaither’s child, but the couple soon divorce, and not long afterward Gaither disappears with his new wife and the child to lead the peripatetic life of a missionary. Lee’s role in this melodrama has gripped him with a subterranean guilt, which rises to the surface only in the wake of the mail-bomb attack, when he convinces himself, despite much contrary evidence, that Gaither is the bomber and is seeking vengeance on him. Even the news that Gaither is long dead fails to move him. Lee’s stubborn misrecognition of the situation is mirrored in the near-universal suspicion cast on him as a “person of interest” in the Brain Bomber investigation: Choi thus establishes a contrived dynamic that links Lee’s attempts to prove himself innocent of the bombing with his belated efforts to examine his past and the failings that have hampered his closest relationships, particularly those with Aileen and their rebellious daughter, Esther. He is ultimately given a heroic, if unlikely, role in the Brain Bomber’s apprehension, a task that, given the novel’s overbearing symbolic logic, is concerned less with the capture of an elusive criminal than with the charting of Lee’s whirlwind emotional progress and dawning self-knowledge. As a conceit, this is creaky. Choi has created a Redemption Machine for Lee’s misspent life, and we can hear its gears grinding as A Person of Interest draws to a close.

And what of the Brain Bomber in all this? He is, unfortunately, little more than a pretext, a device that allows Choi to stage Lee’s inner chaos against the spectacular backdrop of an FBI manhunt and the inevitable media circus that the case attracts. Although the bomber is a minor character, it’s disappointing, nevertheless, to find that unlike Pauline’s relation to Hearst in American Woman, Choi’s reimagining hardly does justice to the enigmatic Kaczynski. The bomber is the novel’s flimsiest creation, and when we finally encounter him in his rural hideout, he displays nothing to suggest convincingly the personality of a terrorist—and certainly not of a man who, like Kaczynski, has been diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic. Instead, he quotes poetry and indulges in flowery, archaic locutions (“bosky line”; “ancient raiment”; “The hermit has his garrulous streak as the jester his tears”). If a novelist is going to borrow conspicuously from well-known events, the adaptation must at least be as interesting as the source material. A Person of Interest fails this basic test. Many features of the true story are inherently novelistic—particularly the agonizing decision, in light of a potential death sentence awaiting Kaczynski, of his brother, David, to go to the FBI and aid its investigation. Readers with even a passing knowledge of the Unabomber case might well speculate what a more rigorous novelist would have done with the same material.

James Gibbons is associate editor at the Library of America and a frequent contributor to Bookforum.