I WOULDN’T DARE COMPARE MYSELF to the legendary actor and singer Billy Porter, but if you were trying to cast a show, circa 2009, we would definitely be up for the same part. Both of us queer, both of us Black, we came to theater—acting, writing, and directing—through music and musicianship, gifts spotted early and cultivated in high school. Both of us have a freakishly high singing voice, although Billy’s is touched by an angel, and mine is more like a fun party trick. This is about where our similarities end, really, but in the business of show, that was more than enough to have the specter of Billy hanging over my every decision as a young actor. When I graduated from the University of Miami in 2011, I was immediately cast in a role that may as well have been invented for Billy Porter personally. Not that he would have accepted what was essentially a glorified ensemble role in an out-of-town tryout for a Broadway show. But I couldn’t stop imagining what his performance would be, and my inability to live up to his extraordinary vocal skill felt like one reason I lost that job.

Fortunately, I haven’t had to live up to anyone, thanks in no small part to Billy himself. Almost everything I’ve been able to accomplish in my career, even while living openly as a queer, genderfluid person, can be traced to the accomplishments of one Billy Porter—the battles he won, the trials he faced and overcame in his devotion to living his truth.

It is important to me, before I continue, that you are familiar with a moment two minutes and twenty-eight seconds into the grainy YouTube video of Billy, in the cast of Grease, performing “Beauty School Dropout” on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno in 1994. Billy’s golden voice—which you may be familiar with from award-winning performances as Pray Tell on Pose or as Lola in Kinky Boots—is at its absolute peak. Technically flawless and utterly raw, the Teen Angel sings to Frenchie, already rooted to the floor by the undeniable power of his vocal prowess, “With what’s left of your career now, you cannot get a j-o-o-o-o-b!” This musical phrase lives in my heart—not the lyric, the phrase. Billy has altered the melody of the original tune, flipped the descending line, and raised it to the heavens, placing it squarely in the most powerful and flexible part of his range. I could sing it for you now, probably in the right key, because of the many college nights I spent playing it over and over, trying to match his every inflection, to nail the riff, to imitate or honor or capture the ineffable thing that makes every Billy Porter performance a star turn.

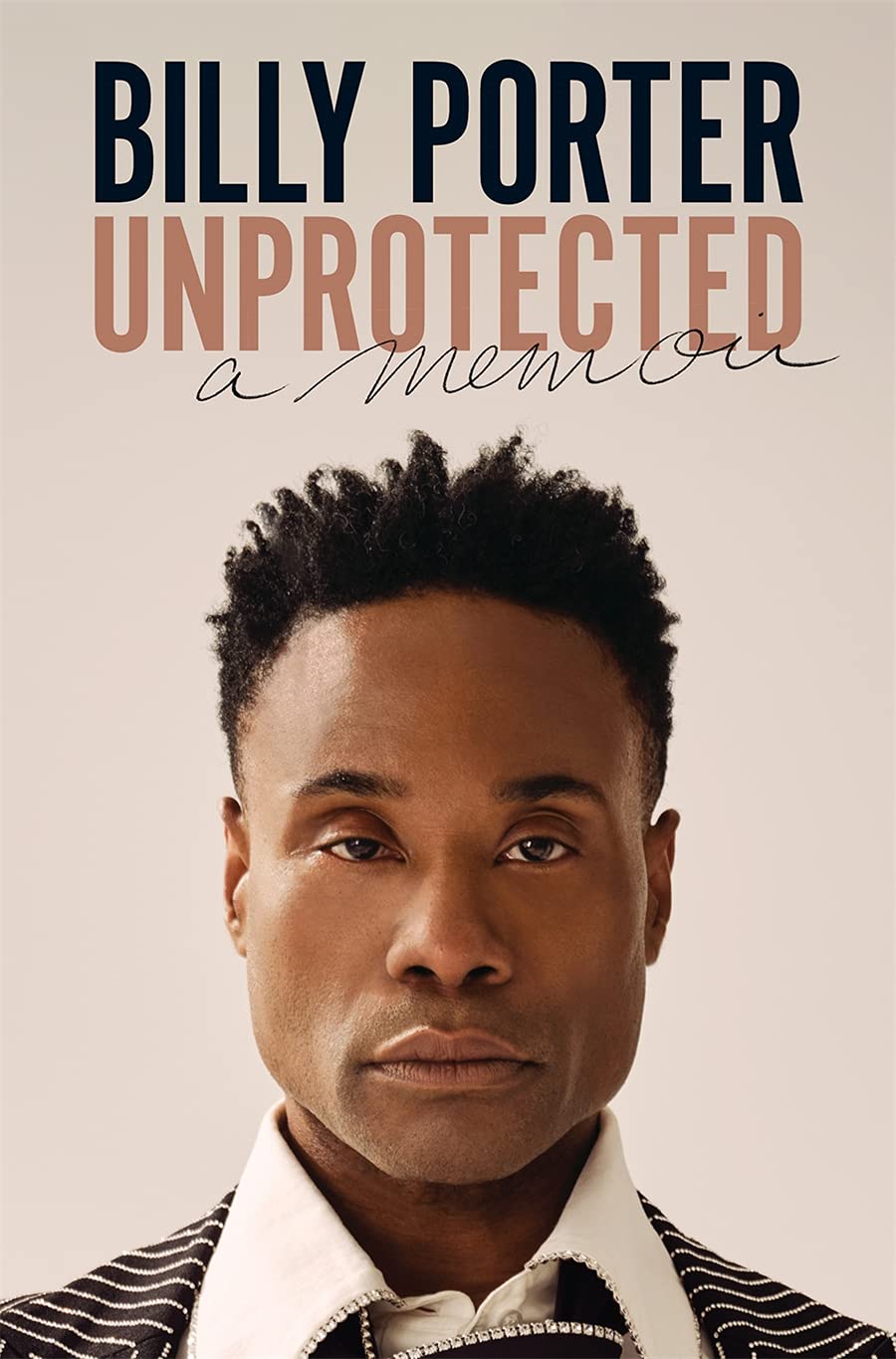

As we learn in his new memoir, Unprotected, Billy has been singing the house down since he was five years old. Back then, in mid-’70s Pittsburgh, he was dubbed “Lil’ Preacher Man” after unveiling his voice in a solo performance of “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” as part of the Friendship Baptist Church Choir. (What I wouldn’t give for a YouTube video of that!) After that moment, Billy knew for sure what I’ve known since the first time I heard him—“God had graced [him] with the gift of song and made him special.” Everyone who hears him sing—his congregation, his drama teachers in middle and high school, Carnegie Mellon professors, casting assistants, producers, directors—comes away changed.

Unprotected is not about Billy’s voice, though, at least not in a literal sense. He frames that voice—this vocal ability that I cannot stop raving about—as his protection, “savior,” and “weapon.” As the book’s title suggests, he sees himself writing now without that protection. But he has other ways of defending himself: wit, sass, projected confidence, his Blackness, his queerness. These are parts of his voice that he’s never without for long. It makes many of the stories seem like two things at once: they are both unprotected and heavily guarded, revealing and defensive, rubbed raw and bulletproof, sometimes alternating so quickly between the two extremes that one might assume that there are two Billys authoring the book. And in many ways, there are. Billy had to learn to fight for himself at an extraordinarily young age. He describes the sexual, physical, and spiritual assaults he’s experienced in brutal detail. (This book should maybe come with a trigger warning—there are graphic depictions of sexual abuse of a minor, and the recounting of bullying throughout his young adulthood culminates in a disturbing, violent episode.) One moment we encounter the present-day Billy we know: self-assured, fabulous, confident-bordering-on-arrogant, capital-S Superstar. The next, we find Billy the child: vulnerable, soft, terrified, struggling to share his pain.

By the time Billy is in college at Carnegie Mellon University, where he has impressively gotten himself on his own merit and his own dime, the voice of the diva is well established. When he encounters adversity in the form of a less-than-A grade in singing and an undeserved probation letter (it’s not entirely clear what he’s being put on probation for, if not for being “too queer”), he explodes:

A B in singing…? For real…? The fucking nerve!

Why is it always my fault? When folks don’t understand me, they just go on the attack. Trying to silence my voice, squash my natural instincts. Anything I say, how I walk, how I sit, how I move my hands and arms are all in the attack zone. I miss my angel Myrna Paris. She was a great voice teacher. She heard me sing and embraced the voice I have. I met her in the ninth grade and she nurtured me. She honored what she did not understand and truly leaned into helping me heal from my vocal nodes and learn how to use my unique vocal power in a healthy way.

Is it present Billy or past Billy who asks why it’s always his fault? The obvious truth is that it’s neither Billy’s fault at all. In the late 1980s, acting programs, even at top-notch ones like Carnegie Mellon, were vicious places for anyone who was not a cis white heterosexual man, full stop. My college experience almost twenty years later featured many of the same aggressions leveled at me for nothing more than who I was.

Even at the darkest moments, Billy comes off as a consummate performer, and the stories are often punctuated with crowd work—conversational interjections like “WERK,” or “yes, gurl,” or “neva liked you bitches anyway.” It feels natural (because I believe this is how Billy talks all the time) but practiced. Like he’s casually sharing his favorite stories of his past with you and ten of your closest friends in a private club’s VIP room. We’re all absolutely wrapped up in the drama and the glory and the powerful voice—not just the singing voice, but the spirit—of present-day Billy, and we know, and he knows, we are lucky to be here. So, are the past moments of vulnerability part of that performance?

When the book is at its best, it feels like the two Billys are in conversation, in communion. Structurally, he leaps across time and space for raw, diary-like chapter intros, outros, and occasional asides, dropping off and picking back up the linear narrative sporadically. He interweaves his present-day vulnerabilities with the hyperconfidence. In that juxtaposition, we see the reality—that Billy is both and neither of these things, wholly; that he is more than his Blackness, or his queerness, or his voice.

As Billy paints it—as any celebrity would—he is oriented toward service, toward making the world a better place, toward calling to action. Here, it feels genuine, in part because he’s not afraid to take some risks. The book calls out hypocrisies across all levels of the business, and Billy uses his considerable platform to name names. If I’m making this sound gossipy or dishy, let me confirm, sometimes it really is. I’d be lying if I didn’t say there were many moments when I was absolutely engrossed in who he’d call out next. But Billy’s real service is in the moments when he’s not trying to perform at all, like the final chapter, which includes many actual diary entries. By sharing as much as he can, he helps others—me, whole generations—feel safe to share more. Even as I wished I was getting a clearer picture of the man, I found myself wanting to shout at him, “Hey, look, you’re doing it, you’ve done it! Can’t you see what you’ve made it possible for me to be?”

It’s funny that the Heath from university ignored the words that accompanied that short phrase of music I memorized from Grease, that I didn’t think to look any deeper than the orange wig and silver space suit. But I think that was Billy’s design. I think Billy at age twenty-three, age sixteen, seven, thirty, fifty-two, has always known how to protect himself. His fabulous persona gives him cover to tell hard truths. See, when he sings, “What’s left of your career now, you cannot get a j-o-o-o-o-b!” you’re not just hearing about how the Teen Angel wants a young girl to go back to high school (frankly, I can’t imagine Billy would want anyone to return to school, not after reading about it here). You’re hearing Billy lament the state of his life and career at that moment and pouring it into the music. I don’t know if he does it consciously, or if it really is a gift from God. When you read about the extraordinary pressures he was under at the time, the raw truth that he was channeling through a basic, boring, and white musical-theater tune becomes obvious. That’s the superstar. That’s the voice.

There’s no way I’d ever be able to imitate that. There can only be one Billy Porter.

Heath Saunders is a writer, composer, lyricist, actor, and diversity dramaturge based in New York.