Albert Mobilio

Frank Bowling, Doughlah G.E.P., 1968–71, acrylic on canvas, 90 × 71 7∕8″. © Frank Bowling. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage, London & ARS, New York. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston IN 1969 THE BRITISH-GUYANESE painter Frank Bowling curated a show at the art gallery of Stony Brook University that included, along with himself, five African […] ![*Sonia Delaunay, _Robes simultanées (Trois femmes, formes, couleurs)_ (Simultaneous Dresses [Three Women, Shapes, Colors]), 1925,* oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 44 7/8". © PRACUSA S.A./Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid](https://images.bookforum.com/uploads/upload.000/id25075/featured00_large.jpg)

Sonia Delaunay, Robes simultanées (Trois femmes, formes, couleurs) (Simultaneous Dresses [Three Women, Shapes, Colors]), 1925, oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 44 7/8″. © PRACUSA S.A./Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid IN 1913, Sonia Delaunay appeared in a Parisian ballroom wearing a dress she had designed. A Cubist patchwork of vivid colors, the garment inspired enthusiastic reactions […]

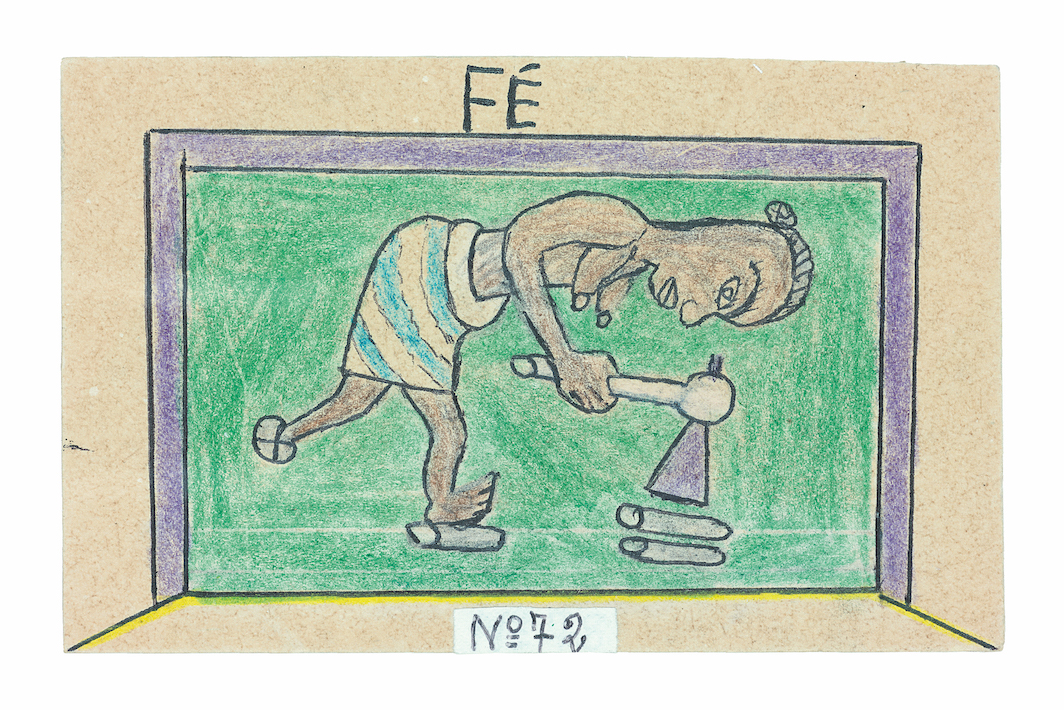

ONE DAY IN MARCH 1948, a twenty-five-year-old clerk in the French colonial administration in Ivory Coast experienced a transformative vision. He reported that the sky opened and “seven colored suns described a circle of beauty around their ‘Mother-Sun’” and that he was then called upon to be “the Revealer.” This divine command would set Frédéric Bruly Bouabré on an investigative path deep into the folklore, language, and religion of his people, the Bété, an undertaking that produced voluminous texts and thousands of drawings, all aimed at elucidating his cultural heritage as the foundation of a universal cosmology. Accompanying a current

Mamma Andersson, Artefakter med Fikus (Artifacts with Ficus), 2021, oil on canvas, 47 1/4 x 35 3/8″. Courtesy the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stephen Friedman Gallery, and David Zwirner FROM CÉZANNE’S APPLES TO LOIS DODD’S CLOTHESLINES, the quotidian world, with its domestic scenes and unremarkable landscapes, has long inspired artists. Their scrupulously focused attention […]

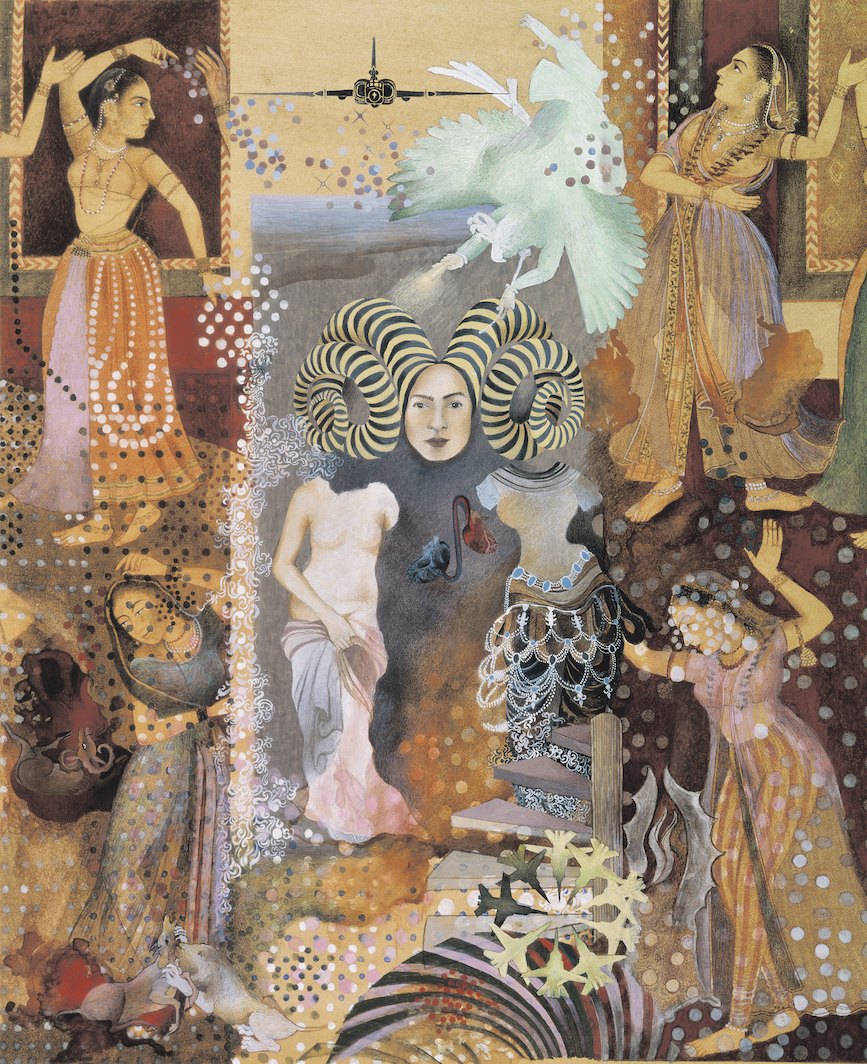

Shahzia Sikander, Pleasure Pillars, 2001, vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, and tea on wasli paper, 17 x 12″.© Shahzia Sikander/Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York/Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee. UPON HER ARRIVAL at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1993, Pakistan-born artist Shahzia Sikander was asked by an instructor if she […]

IN 2011, WINFRED REMBERT HAD ACHIEVED a sufficient measure of fame to be invited back to his hometown of Cuthbert, Georgia, to celebrate his success as an artist. Rembert’s artworks were sought out by collectors and hung in various galleries, including the Yale University Art Gallery. Growing up in Cuthbert in the 1950s and ’60s, Rembert was subjected to police harassment and beatings and, on one occasion, nearly lynched. He had been paraded through town in chains before being sent to prison. But now Cuthbert was honoring its native son with Winfred Rembert Day. He was presented with a plaque

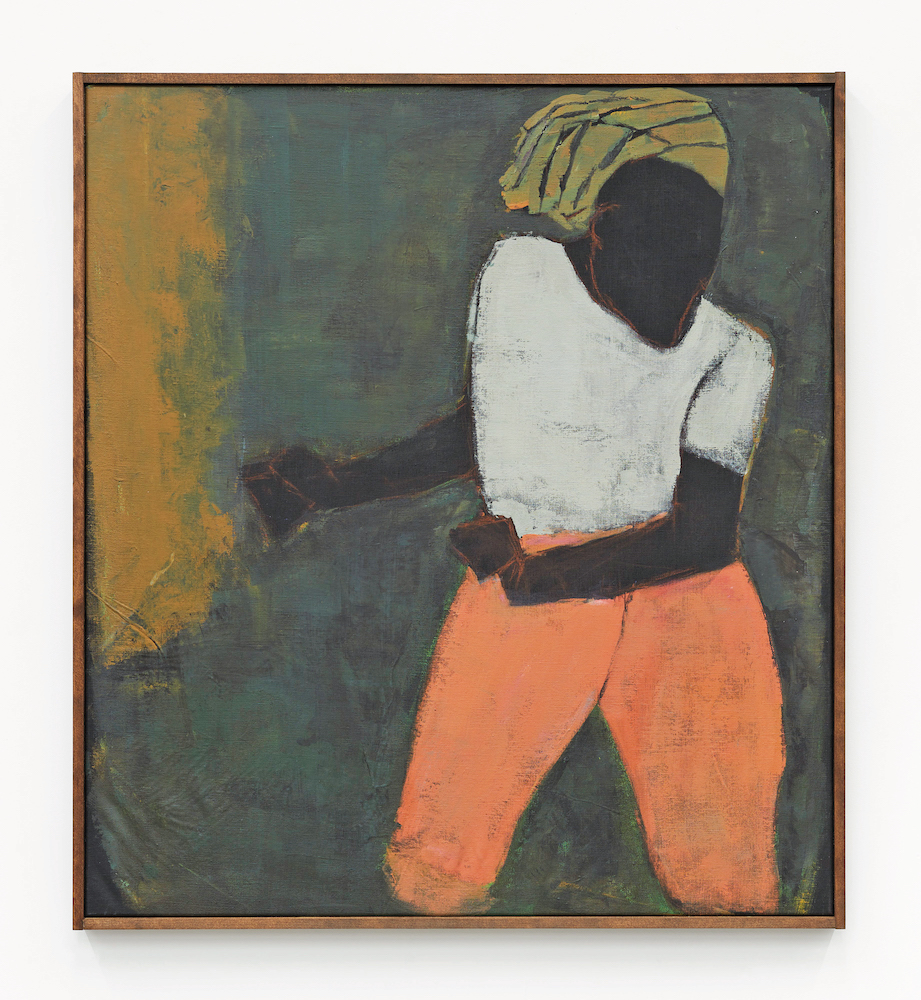

Reggie Burrows Hodges, Community Concern, 2020, acrylic and pastel on linen, 40 x 36”. BROAD SWATHS OF VARIEGATED COLOR animate Reggie Burrows Hodges’s canvases at least as much as his energetic subjects: unicyclists and hurdlers; basketball, tennis, and baseball players. Born in Compton, California, he attended the University of Kansas on a tennis scholarship and […]

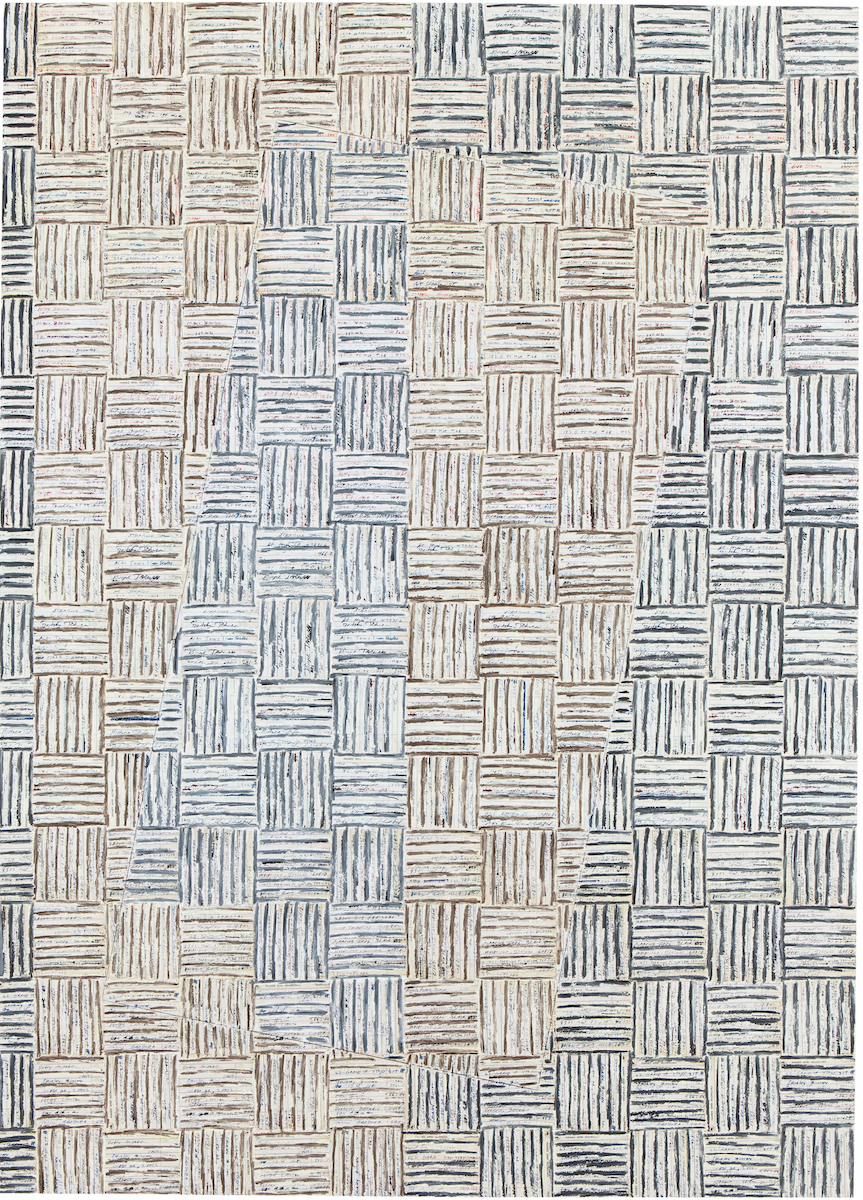

McArthur Binion, DNA:Study:X, 2014, ink, oil paint stick, and paper on board, 64 x 46″. McArthur Binion, DNA:Study:X, 2014, ink, oil paint stick, and paper on board, 64 x 46″. MCARTHUR BINION EMPLOYED his tattered address book, containing nineteen years’ worth of annotated contact information, as the substrate of numerous paintings and prints in his […]

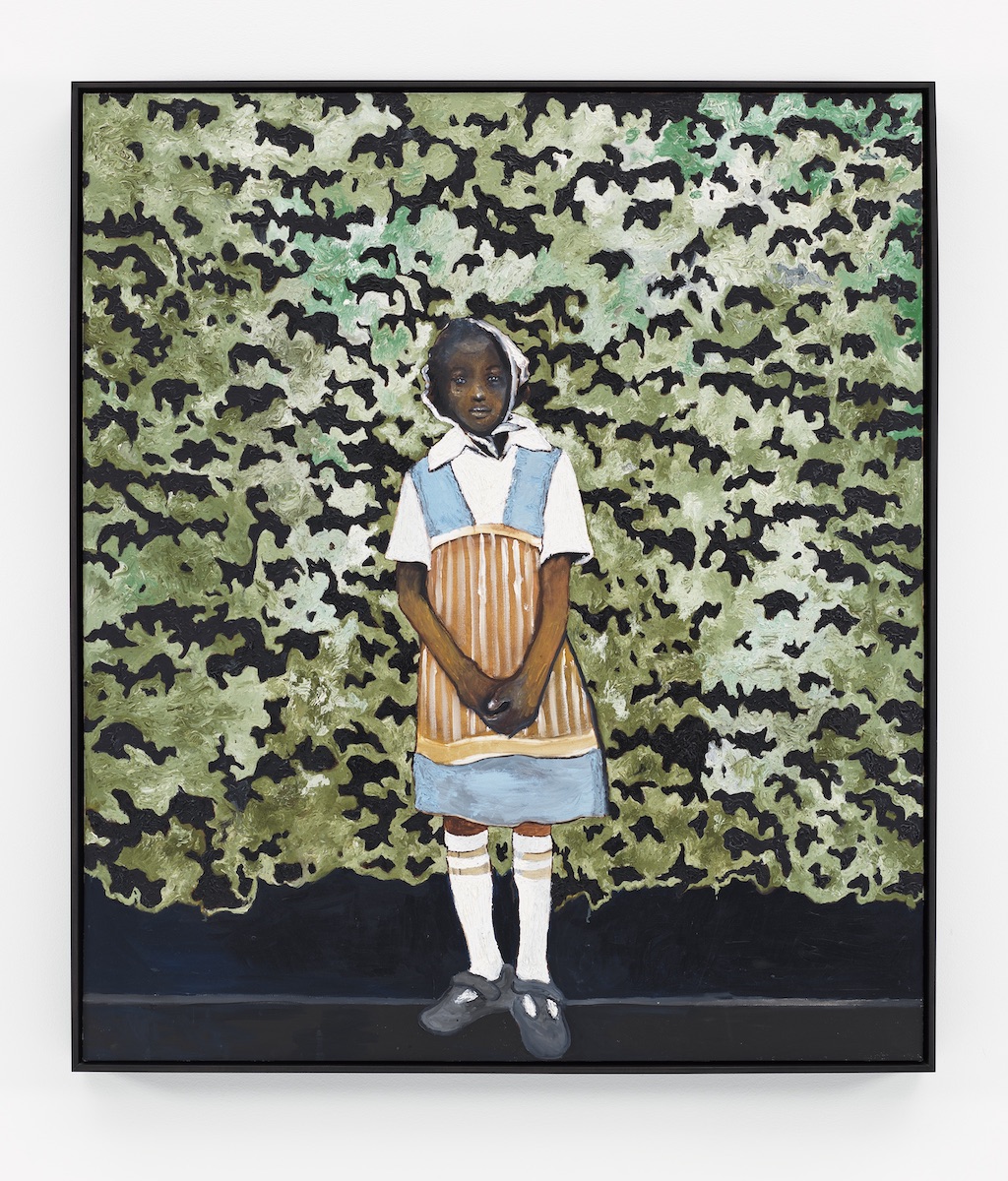

Noah Davis, Mary Jane, 2008, oil and acrylic on canvas, 60 × 52 1/4″. Courtesy and © The Estate of Noah Davis, Private collection of Michael Sherman and Carrie Tivador PROTEAN PAINTER NOAH DAVIS had emerged as a catalytic force when he died of cancer at age thirty-two. His swift evolution promised an exciting future, […]

Know thyself, the ancient philosopher said. Graph yourself, might be New York–based artist Andrew Kuo’s reply. By slice and dicing his stream of neurotic consciousness into flow charts, pie charts, and bar graphs, Kuo renders quotidian thoughts, worries, and speculations as quantifiable and official looking as GDP projections from the Congressional Budget Office. His images—marked by a gleefully saturated palette and puzzle-like complexity—play against staid expectations, calling to mind artists like Gene Davis and Barnett Newman rather than your Econ 101 textbook. The highbrow gloss notwithstanding, Kuo candidly depicts intimate preoccupations. Some are intellectual and reflective, such as “My Selected