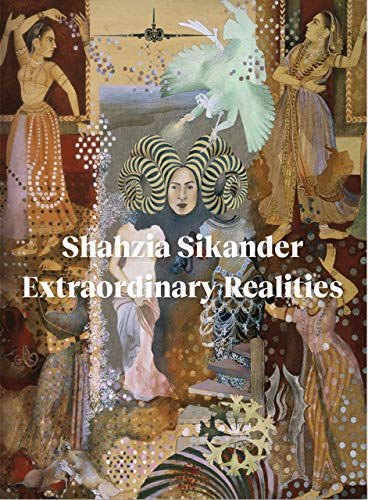

UPON HER ARRIVAL at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1993, Pakistan-born artist Shahzia Sikander was asked by an instructor if she was there “to make East meet West.” In this volume’s interview with Vasif Kortun, Sikander goes on to note that “no one else was asked such a question,” and that she “became aware very quickly that America was about a black-and-white relationship, where being brown was not yet fully visible.” As an undergraduate in Lahore, Sikander had produced The Scroll, a watercolor depicting daily life that won national recognition for its adroit engagement with the Indo-Persian tradition of miniature painting. Her experience in the United States, particularly in the wake of 9/11, brought the country’s habit of binary thiniking—of reflexively creating the other—into sharp focus. She has since explored this tension in art and films that retain the visual language of miniature painting to dramatize themes such as diasporic identity, gender, militarism, and racism. In Pleasure Pillars, the artist’s self-portrait, one in which she sports elaborately curled ram’s horns, occupies the center of the watercolor. Surrounded by an assortment of female archetypes, she appears to float above the headless torsos of Venus and a Hindu goddess. A fighter jet and a dragon-like bird hover above the entire scene, situating female representation within the context of the global war on terror. Rich with symbolic interplay, Sikander’s images reward close reading that may or may not decode their meanings. (The pair of snuggling rodents in the corner of the image yields less readily to interpretation than the adjacent military planes arranged into a floral pattern.)

But Sikander’s art is hardly a hermeneutic chore; the lush complexity of the images is matched by their entrancing beauty. Her watercolors have been washed in tea and executed on wasli paper, the material used by Mughal-era painters. Appearing at once contemporary and aged, these works bridge time as well as personal and public experience. If Ready to Leave draws the viewer into its layered signifiers, it does so through Sikander’s elegant orchestration of geometric patterning and expressionistic gestures. Sinuously mutating circles appear throughout her work; here, they serve as kinetic focal points that activate the eye. About its creation, the artist has commented: “Becoming the other, the outsider, through the polarizing paradigm of East/West, led to an outburst of iconography of fragmented bodies, androgynous forms, mythical creatures of multiple identities.” Sikander’s art dissolves boundaries amid a provocative assemblage of motifs. Within her immersive and vertiginous realm, no compass suffices.