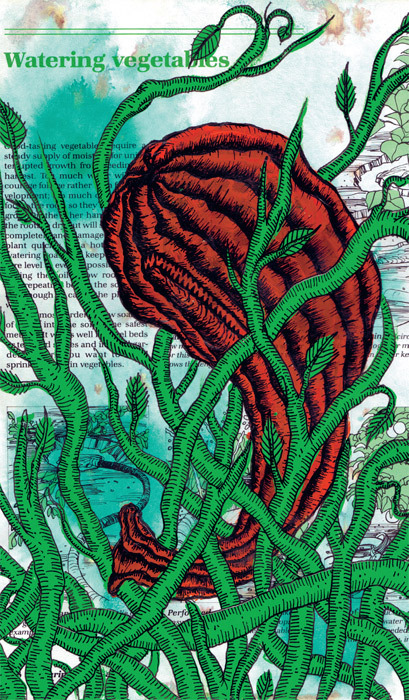

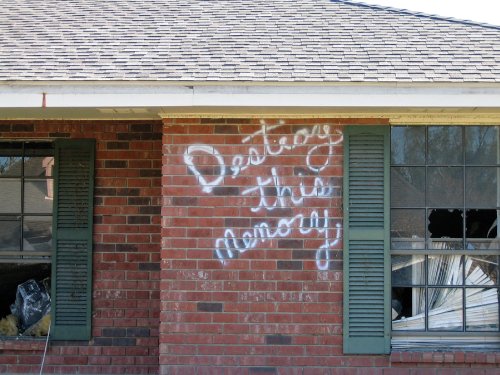

Marcel Dzama: Sower of Discord

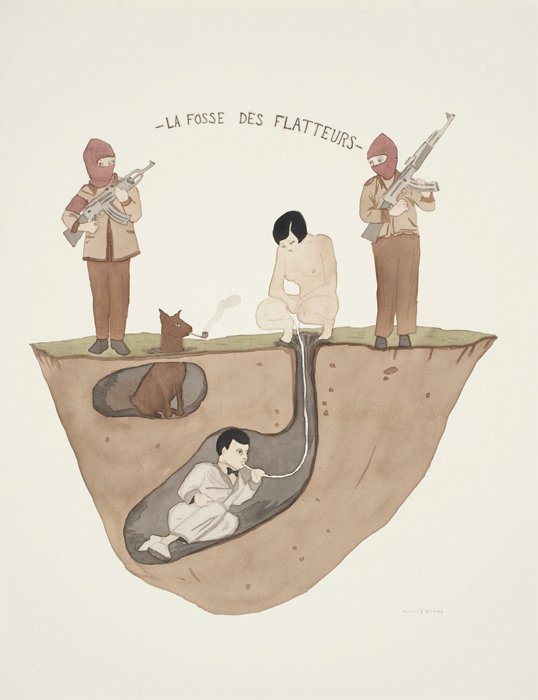

IN THE EIGHTH CIRCLE of Dante’s hell reside the Sowers of Discord, those who have caused divisiveness in their families, cities, and faiths. The poet, deploying his ever-apt touch with punishments, describes them being sliced and diced by a demonic swordsman. Since the late 1990s, Marcel Dzama has populated his ink-and-watercolor drawings with sundry dismemberments and wounds accomplished by swords, knives, arrows, guns, bats, and the occasional mace; the malevolent images may be inspired by hellish doings, but this is hell as circus ring or costume ball. Dzama’s discord sowers are a curiously