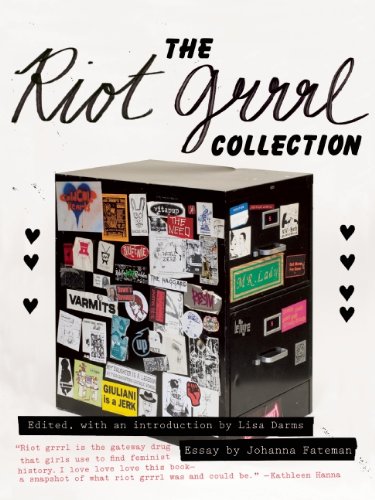

The 1990s punk feminist movement Riot Grrrl has had a resurgence in recent years, in books such as Sara Marcus’s Girls to the Front (Harper Perennial, 2010), films like The Punk Singer, and the establishment of the Riot Grrrl Collection at NYU’s Fales library. The Feminist Press has just published The Riot Grrrl Collection, which presents vivid reproductions of zines, flyers, and other works from the Fales archives. Editor and archivist Lisa Darms recently sat down with The Riot Grrrl Collection contributors Kathleen Hanna and Johanna Fateman to discuss the book, answering questions submitted by novelist Sheila Heti. The following is a condensed and edited transcript of their conversation.

Lisa Darms: Here’s Sheila’s first question (reading), “I remember not calling myself a Riot Grrrl then, though I knew it and admired it. I somehow didn’t feel like I really belonged, nor did I want to. This seems common to me. Who were the people who called themselves Riot Grrrls, and who were the people who basically were Riot Grrrls, but didn’t call themselves that? Which camp did you fall into?”

Kathleen Hanna: I never called myself a Riot Grrrl, but I felt like I was a part of the Riot Grrrl movement. At the time, I felt like all Riot Grrrl was to me was a branch of feminism that had to do with punk rock music and the scene, the punk rock scene.

Lisa: I think there’s a perception now that one was a card-carrying member of Riot Grrrl, and I don’t think that was true even for the people who were most closely associated with it. I wasn’t a Riot Grrrl: I never went to a meeting, and never thought of myself as part of the movement, even though I read the zines, was really into the music, and am a feminist. But I think that’s probably true for the majority of people, and that’s what I say when I talk about the collection—that the borders of what Riot Grrrl is, and who a Riot Grrrl was, are really permeable.

Johanna: For me, I find the term Riot Grrrl most useful retrospectively in that it describes the era of feminism that I came of age in, and my artistic sensibilities. At the time no one I knew would say, “I am a Riot Grrrl.” It was more that people on the outside would identify you as a Riot Grrrl, from the way that you looked, dressed, or bands you were into, but I don’t remember people saying, “I am a Riot Grrrl.”

Kathleen: Yeah, it was so much more loose-knit than people thought. And even though most people didn’t call themselves Riot Grrrls and some were even like, “I am not a Riot Grrrl,” they were doing feminist things, and that was really exciting. It never bothered me that people didn’t call themselves Riot Grrrls. And I remember people thinking that it would bother me. Saying “I’m not that! And that’s gonna piss you off,” and I was like, I don’t care what you call yourself. You can call yourself Martha Washington.

Lisa: If you read the zines and stuff from the era, people are saying that in the moment: If you feel like you identify with anything we’re saying then you might be a Riot Grrrl, you might not.

Johanna: Part of it was this slightly juvenile “don’t put me in a box”–type mentality.

Kathleen: Don’t label me . . .

Johanna: So now I’m proud to say I’m a Riot Grrrl. And I also sometimes think, “what would a Riot Grrrl do?” when I’m faced with a certain situation, and it definitely can bring you back to a certain kind of mind-frame, of like brattiness or irreverence, which is still valid and useful to me.

Lisa: Maybe our next book should be a self-help book: What Would a Riot Grrrl Do?

Lisa: This next question is about the media ban. Do we want to talk about the media ban?

Kathleen: I don’t know anything about that—that’s what is so weird; there was supposedly this moment when somebody called a media ban. I remember in DC it just became where the meetings were no longer about anything other than, “I’m really mad about this article,” and it was like, let’s just not deal with it.

Lisa: So you think it was more like individuals deciding they didn’t want to engage with the mainstream media?

Kathleen: Yeah, and being pissed off about articles and stuff. Some people tried to get involved with the media and it’d be like, “hot girls wearing baby barrettes and short plaid skirts are yelling about their dads raping them,” or something. It was sexualized and really gross. But I did have this thing where Jessica Hopper, who’s now a music writer, did an article for Seventeen magazine after people had sort of decided not to deal with the media. I think the Minneapolis group had a vote, and she was kicked out of the group. In some articles it was my fault, like I had told all these girls to kick her out. And I remember being really insulted at how sexist that was, that women couldn’t make their own decisions. I didn’t kick her out of Riot Grrrl, I didn’t have that kind of power. I wasn’t the president of Riot Grrrl, I was just someone who helped start the meetings and went to meetings for a while.

Lisa: I think that’s really interesting. An article spread misinformation about something that then becomes history and now we all believe—in general—that there was a media blackout that never really existed; I mean, other than on an individual level?

Johanna: I think it did exist, though. I just don’t think that any of us were personally involved with it. I know this from Sara Marcus’s book that some Riot Grrrl chapters made an agreement not to talk to the press to try to regain some control. Stuff like that seems in retrospect… I mean, imagine a media blackout today.

Lisa: Well, that’s what Sheila’s question is about. We already talked about how we experienced the moment—I didn’t, because I wasn’t really a part of it—she writes that it feels unlikely that any movement would or could make that decision today. Do you agree? Do you think the so-called ban was good for Riot Grrrl?

Johanna: Now, I think the so-called blackout added to the mystique of whatever was happening, and it’s a good part of the story. Maybe the story that there’s a media blackout said more than any interview ever could about Riot Grrrls.

Lisa (reading): “Is there something the mainstream of young women today don’t know that this book, and the example or Riot Grrrl in particular (as opposed to feminism in general), could help them with, or teach them, or tell them? If so, what in this book could help young women today?”

Johanna: I think obviously something that has not changed for young women in this country, or anywhere really, is that sexual abuse and rape are huge problems. With Riot Grrrl there was this ethic that we could get together and do something. There has to be more than going to the authorities, especially when it’s the authorities who are involved with covering up, or perpetrating, sexual abuse, or protecting athletes that they value more highly than girls. I just think that there’s a spirit there that we need to celebrate and cultivate in girls and children and teenagers—that there’s a way to resist through friendship and art.

Kathleen: I still have sixteen-year-old girls coming up to me saying they just found out about Riot Grrrl. They really want to see the zines. They really want to know more about it. And a lot of times they say, “I wish I lived in the nineties,” and I’m like, “No, you don’t…” but they say, “I wish I was a Riot Grrrl, I wish Riot Grrrl existed now.” I think this book presents an accurate/inaccurate portrait. It shows that Riot Grrrl wasn’t this cohesive thing that had a president and a treasurer, it was all over the place and people had really divergent ideas. To these young girls who have a real hunger to know more about Riot Grrrl and I feel like instead of saying, “oh, this is what Riot Grrrl is,” now I can say, “look at this book.”

Lisa: The hunger for this material that I’m encountering isn’t just from girls, there’s a really strong interest from young men, which I’m really excited about. Because it really was a boy/girl revolution as well as being a girl revolution.

Kathleen: Totally.

Lisa: I thought this one was interesting (reading) “Have your attitudes about sex and power and women changed since that time? Can you delineate a few areas in which your ideas about sex relations and power relations and women’s place in culture and society and women and sex, etc., have changed most dramatically? Are there things you see and know now because of experiences you’ve had in the world that weren’t apparent then?”

I think this question appeals to me because everyone had their own way of being excited about Riot Grrrl, and for me—even before I ever heard of Riot Grrrl—it was something that I got more from the L7 strain of punk. I mean, I remember the first time I heard of or saw L7 it was like: What. The. Fuck. Holy shit, dude. This is what I want and need. Because I had come from this punk scene where I was a “slut,” but I was a feminist, I was raised as a feminist and so it was really confusing for me to try to reconcile these different parts of my experience. So the way that I tried to access that was through the concept of power and, again, this was before I heard of Riot Grrrl. It was: “I can be a powerful and sexy woman.” I think what I really like about Riot Grrrl is that it also acknowledges that a really big part of being a young woman—or a woman of any age—is the experience of danger and sexual violence.

Kathleen: Well, what does that do to your sexuality? If sex is associated with violence and with your reputation being ruined, and then in the age of AIDS, also that, and then also pregnancy if you’re having sex with men, it’s like, what does that do? Like you originally said, danger, it’s equating sex with this bad thing, this danger, and I feel like one of the cool things about Riot Grrrl was saying, “you’re not a slut. It’s okay to like sex.”

Lisa: That just leads back to why Riot Grrrl was important, and what you were saying earlier about knowing that you can organize to protect each other and knowing that you don’t need to rely on so-called authorities to protect women against sexual violence. Had I encountered Riot Grrrl younger, I think that I would have felt a lot safer in trying to enact that experiment of being a sexual, powerful teenager.

Johanna: Fighting back against sexual violence but also celebrating sexual experimentation or adventure is pretty tricky. I think we did kind of a good job of that, you know?

Kathleen: I know how I’ve changed in terms of things I’ve made that I would maybe edit better, or stuff I’ve put in writing that I’m now like (groan) and am definitely learning that sexism damages men as well and makes them have to cut off part of their own personalities to fit into traditional roles. And that these roles hurt everybody. It doesn’t just hurt women. I think that’s something that I’ve grown into and that I thought for a while, but now I feel more like it’s a part of my skin and my practice and the way that I live.

Johanna: I would say the same thing for myself and that I feel much more empathetic with men. I can see how it’s painful for them to conform to whatever sex and gender roles they feel that they need to conform to and I don’t see it as that different.

Lisa (reading): “Has nostalgia distorted things about the movement? What are the main distortions?”

Kathleen: I do a lot of interviews and stuff where they ask me about it and I feel like the nostalgia is this happy thing where it’s like, “oh, I wish I lived in the nineties, it would be so awesome! There was this community and it would be so great.” My experience of it was that it was not that great, and a lot of people don’t know about the violence at shows and how much shit bands with women in them—especially explicitly feminist bands—took. And so when people are nostalgic about it, I’m like, oh, you want to go back to a time when if you were onstage and you said, “there’s a pro-choice rally happening,” there could be a guy who’s yelling “shut up!” while you were talking, and possibly had a knife in his jacket. And nobody would do anything about it. You know, and a lot of times girls just weren’t safe at shows. And I don’t know if they are now, I definitely know that at some shows they’re not. The nostalgia erases a lot of the negative things that happened and when I talk about that in lectures people are very shocked.

Lisa: And that’s documented in the archive for sure, that element of danger and violence. I like to think about the word nostalgia because it’s part of my job as an archivist. I think the way we normally talk about nostalgia is something that’s really simplifying and reduces complex histories into just a few narratives. But sometimes, because nostalgia is so disparaged I ask myself, well, are there any positive aspects to nostalgia? To me nostalgia is a yearning, and I think: How can we use that yearning and that longing in a positive way? So, the danger of nostalgia is that it’s reductive, potentially, but there’s also a power there that I as an archivist and an historian would like to exploit.

Kathleen: I think something can start as nostalgia and lead into learning about history—about a complicated history. I don’t really believe that there’s this “authentic experience” that’s being portrayed; there are flaws. Flaws that are documented in the archive, and in the book, and showing that is what counteracts nostalgia.

Johanna: I would hope that in the nostalgia for that moment, in which the cultural output of teenage girls got some attention, that people would then extrapolate, and really begin to value the creative lives of teenage girls, because I think that they’re so degraded in our culture, so dismissed as consumers and frivolous or whatever, and this book is such a testament that teenage girls can be philosophers, and artists, and revolutionaries.