Mel D. Cole, New York, NY 5.30.20, 2020. IN DECEMBER 1964, the activist Fannie Lou Hamer stood beside Malcolm X in Harlem during a rally. Hamer described how, while once traveling to a voter-education workshop, she was arrested and beaten with a blackjack. Facing her listeners in Harlem, Hamer spoke of how that experience led […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2021

- excerpt • August 24, 2021

The lanes of the cemetery were overgrown, lined with slender conifers whose branches were heavy with rain. I had been pushing the bicycle with my head slightly bowed, and when I looked up I realized I was back at the entrance. I had come full circle. I checked the cemetery map again—I had followed the steps exactly—then continued back in the direction I’d come, hoping to find the gravesite from the opposite direction. In no time at all I was lost. The paths were not marked, and there was no one I could ask—the only other person I’d seen, a

- excerpt • August 20, 2021

There is an important distinction between what Nancy Fraser calls “affirmative change” and actual transformational change. The former is perfunctory, form-filling, intended to silence and appease; the latter requires the dissolution of underlying structures and hierarchies for a complete reformulation. Whether it is the National Organization of Women or an organization like Amnesty International USA (AIUSA) or even the Women’s March, all require transformational change. This means reconsidering everything, from the way meetings are organized and conference calls are set up to the way public demonstrations are organized. The go-to for most organizations, sadly, is affirmative change: the installation of

- excerpt • August 18, 2021

Meaning—or narrative—isn’t always what we see, or even look for, in images. In 1868, following the International Exposition in Paris, the Italian novelist and essayist Vittorio Imbriani published “La quinta promotrice,” a collection of his observations and theories on contemporary European art. This included his theory of the macchia, which Teju Cole describes as “the total compositional and coloristic effect of an image in the split second before the eye begins to parse it for meaning.” Approaching a painting, one is most likely to see before anything else its arrangement of colors, shapes, shadows, and space, and only afterward begin

- excerpt • August 10, 2021

For a number of years in the late 2000s and early 2010s, Dave Hickey’s byline in magazines said that he was working on a book called Pagan America. There’s even a ghostly record of the title on Google Books, with a precise page count and ISBN, as though the manuscript were finished, paginated, and catalogued, but then withdrawn and locked away in the writer’s desk, left to be published, if ever, posthumously.

- review • July 12, 2021

Early in Werner Herzog’s 1974 documentary The Great Ecstasy of the Woodcarver Steiner, we find its subject, a champion “ski-flier,” in the studio where he works as an amateur woodcarver. Brushing his hand over a tree stump, Walter Steiner describes the forms his chisel will release: “I saw this bowl here, the way the shape recedes, it’s as if an explosion had happened, and the force cannot escape properly and is caught up everywhere.” Trapped force is not to be the film’s subject. Rather, its subject is fear—or, as Steiner calls it, “respect for the conditions.” From the ski-jump at

- excerpt • June 22, 2021

Noah Webster’s influence reached far beyond the pages of the dictionary or the speller. Even those Americans who have never read his work or heard his name are still bearers of his legacy. He shaped the underpinnings not only of American education and language standardization but also of the nation as a whole. The idea that America was a new experiment capable of surpassing Europe, the notion of a nationalism based on uniformity, the belief that the United States was a sort of country on a hill—Webster cemented and spread these ideas through the building blocks of language itself. The

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

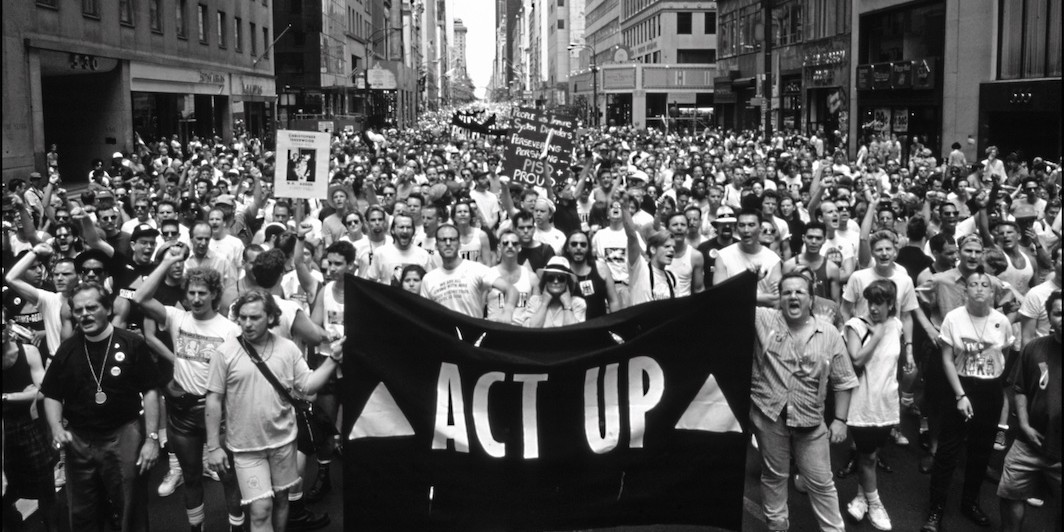

ONE NIGHT IN 2010, the writer Sarah Schulman was at the Manhattan gallery White Columns for the opening of a show she had helped create about the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power, or ACT UP, the AIDS-activist organization she was a member of from 1987 to 1992. In her 2012 book The Gentrification of the Mind, Schulman writes of the evening as a kind of reunion for the group, with the ACT UP-ers, mostly in their fifties and sixties, “laughing and smiling and hugging and flirting,” all wearing the scars, physical and psychic, of the traumas they had endured together

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

“AT THIS POINT, you probably should take several deep breaths in order to relax, there is much more to come, if you’ll pardon the expression,” cautions Wilson Bryan Key, in the first chapter of his 1973 pulp best-seller Subliminal Seduction. The book, which ignited one of the Cold War era’s more banal panics—that the advertising industry is a black site of veiled salacious messages—is best remembered for its analysis of an ad for Gilbey’s gin, which Key claimed contained the letters S-E-X embedded in ice cubes. But Key goes on to argue that television and magazine ads contained stronger stuff

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

WHEN PEOPLE TALK ABOUT TRUTH OR DARE, the notorious 1991 documentary about Madonna’s Blond Ambition tour, they tend to mention the same handful of scenes. The gay kiss. Madonna deep-throating a bottle of Vichy Catalan (not Evian, as often misremembered). Kevin Costner calling the show “neat” and Madonna making a puking gesture. Are these the best scenes in the film? No, but they passed for scandal in 1991 and so they made an impression. In retrospect they feel a little try-hard, a little overhyped, but that’s because we’re watching from the world Madonna made. With the distance of thirty years,

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

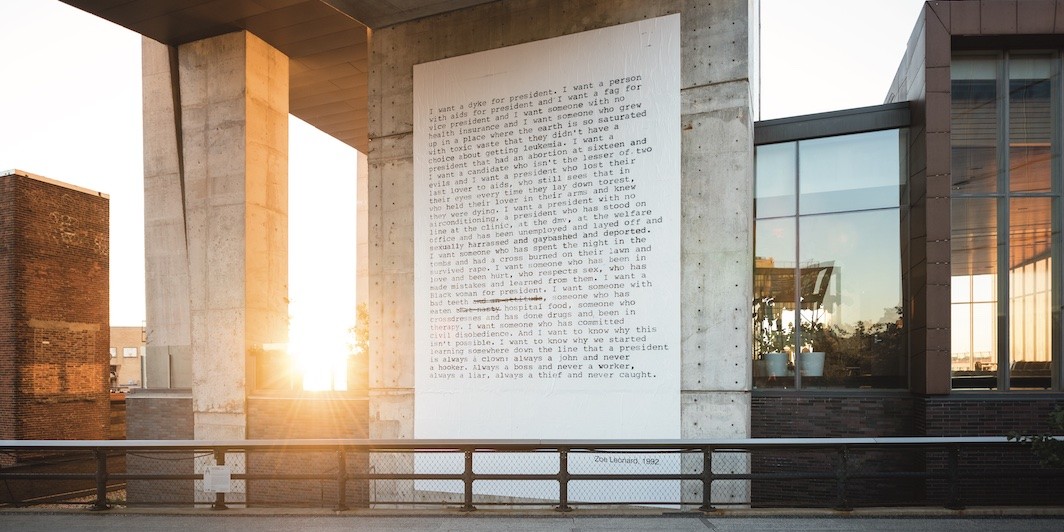

MANIFESTO IS THE FORM THAT EATS AND REPEATS ITSELF. Always layered and paradoxical, it comes disguised as nakedness, directness, aggression. An artwork aspiring to be a speech act—like a threat, a promise, a joke, a spell, a dare. You can’t help but thrill to language that imagines it can get something done. You also can’t help noticing the similar demands and condemnations that ring out across the decades and the centuries—something will be swept away or conjured into being, and it must happen right this moment. While appearing to invent itself ex nihilo, the manifesto grabs whatever magpie trinkets it

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

FOR NEGATIVE LESSONS, the “don’ts” when it comes to writing reviews, there’s always the internet. But for direction and inspiration, cold water on a face flushed from a looming deadline, it’s better to have hard copies of whatever you think defines greatness: you can open one to a random page, like shaking a Magic 8 Ball, and ask it what to do. Jenny Diski’s new, posthumous collection, Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told?, might give an answer—ultimately, obliquely—to its own title’s question. Of course it can’t answer mine. But I’m sure I’ll periodically give it a try

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

Panel from Gary Panter’s Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise (New York Review Comics, 2021). © Gary Panter GARY PANTER’S COMIC STRIPS ARE FUN TO LOOK AT AND HARD TO READ. “My work,” he’s admitted, is “not very communicative.” Panter made his mark as a poster artist in the late-’70s Los Angeles punk scene, established his reputation […]

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

RICKIE LEE JONES’S BLOND HEAD IS ATILT as she lights a French cigarette, crowned with an off-center red beret. It’s that image of the artful-dodger “duchess of coolsville” (as Time dubbed her) on the cover of her eponymous 1979 debut that became iconic to a public who still recalls her mainly for that year’s jazzy top-10 single “Chuck E’s in Love.” It was a sell, but one close to the reality of this former teen street kid and, more recently, poverty-line Venice Beach bohemian. Jones rejected the 1970s “glamour-puss” gloss that was being urged on her and brought her own

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

THE LAST FILM I SAW IN A THEATER was Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, at BAM Rose Cinemas in February 2020. Of course it didn’t occur to me that this would be the last movie I’d see on the big screen for well over a year—why would it? I hadn’t gone more than a month or so without visiting a movie theater since I was sixteen. Thirty years of movie after movie, Jurassic Park to Jeanne Dielman. Art houses and multiplexes; malls and drive-ins. All abruptly shuttered, some forever.

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

I’D LIKE TO DESCRIBE AN ORDINARY ENCOUNTER WITH GENDER. Which is fiction. I walk into a hardware store and I ask where the spray bottles are. He directs me. He-seeming person. I grab one and walk back to the register. I shove it toward him and he goes “three-oh-mmph.” I don’t know what the mmph is. I say what. He says if you give me four cents (as I hand him a five) I can give you back two dollars. I know how it works I explain. He hands me the two dollars and then says thank you ma’am. Now

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

FOR OVER FORTY YEARS, Lorraine O’Grady’s work has argued against binary thinking. Instead of either/or, she proposes a both/and construction, often expressed by pairing two images in a diptych. Take her 2010 Whitney Biennial work The First and the Last of the Modernists, in which she juxtaposes portraits of Charles Baudelaire with Michael Jackson, tinting them in red, gray, green, or blue. As she wrote in 2018, “When you put two things that are related and yet totally dissimilar in a position of equality on the wall . . . they set up a conversation that is never-ending.”

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

AMERICA, IT SEEMS, WOULD LIKE A COOKIE. After centuries of literally and figuratively relying on Black women while simultaneously shoving them toward the margins of public life, conspicuous acknowledgment has become en vogue. The market now chases our purchasing power and the electoral establishment has recognized our political power and cultural institutions have added us to their guest lists. It has never been easier to find the right shade of foundation. Kamala Harris’s smile greets visitors to federal buildings around the country; Stacey Abrams is approaching household-name status. In return, America wants that cookie.

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

TWENTY YEARS AGO, the Cannes Film Festival made a concerted effort to bring in more Hollywood fare. This may explain why Shrek showed in the 2001 competition up against works by Shōhei Imamura, Michael Haneke, Jean-Luc Godard, and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Baz Luhrmann’s musical Moulin Rouge! opened the festival before going on to worldwide box-office success and eight Academy Award nominations. At one point in Luhrmann’s film, the impresario advises Nicole Kidman’s character to renounce the man she loves in favor of the powerful duke to whom she has been promised so that the jealous aristocrat will not put out a

- print • June/July/Aug 2021

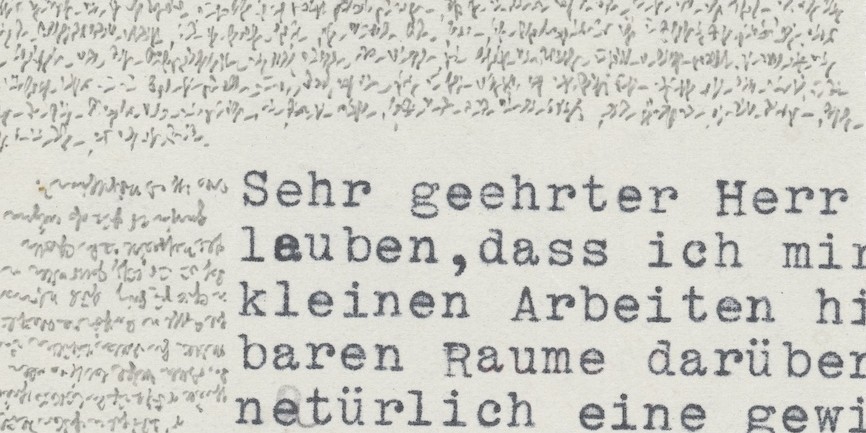

ROBERT WALSER WAS A SWISS WRITER of the early twentieth century who wanted very much to be a German writer. He walked and walked more than he wrote and wrote, covering thousands of miles in his lifetime, albeit within limited territory. In the beginning his garb was clownish—“a wretched bright yellow midsummer suit, light dancing shoes, an intentionally vulgar, insolent, foolish hat”—near the end a motley of patched rags, and at the very end a shabby but proper suit and overcoat, his death duds when he collapsed in 1956 in the snow near the mental asylum where he had resided