BECAUSE THE MAKING OF EVERY single motion picture has its uphill battles and its moments of high drama, and because a film can reflect its times in fascinating ways, a book about the making of John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969) could very well be a compelling read, even though the movie itself is as phony as its central hustler Joe Buck’s cowboy credentials. That the United States is the land of the sham is part of the film’s hammered-home point, and to emphasize this Schlesinger lingers attention on the garish billboards and urban signage that posh visiting European filmmakers often fetishize as proofs of American crudity and commercialism—though looking back from a present day in which our downtowns are muted affairs overrun by WeWorks and Sweetgreens, all those bright lights appear rather festive, even beautiful.

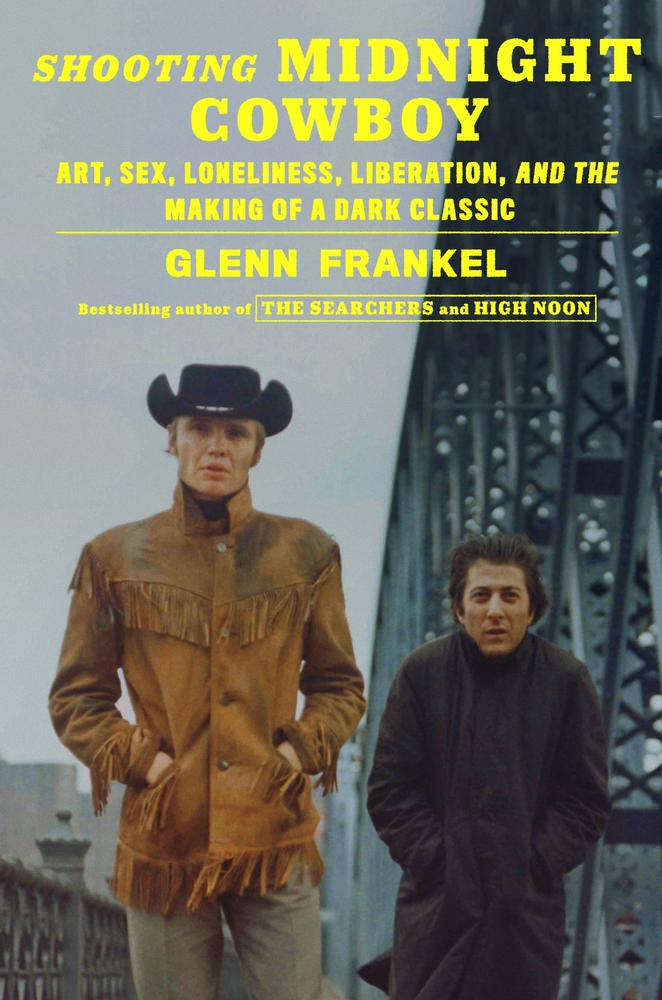

In Shooting Midnight Cowboy: Art, Sex, Loneliness, Liberation, and the Making of a Dark Classic (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30), author Glenn Frankel’s framework for situating the movie extends far beyond its Manhattan setting. He draws out the biographies of the major personnel involved in the making of the film; offers a detailed chronicle of its preproduction, production, postproduction, and reception; and takes extensive digressive detours into pockets of cultural history leading up to and beyond the watershed moment when a movie about a hunky piece of Texas trade making it with men and women in an increasingly dilapidated New York City could become a surprise hit and popular phenomenon.

Frankel takes pains to illustrate just how many talents contribute to the success—or failure—of any film, dedicating significant space to often less-heralded figures in the moviemaking process. Coming in for close-ups are casting director Marion Dougherty, who campaigned for a then virtually unknown Jon Voight to star as Buck, and costume designer Ann Roth, who provided Buck’s iconic suede jacket and the bargain-bin peacock look of Dustin Hoffman’s Ratso Rizzo’s wardrobe, much of it scraped together from surplus stores in and around Times Square.

But Frankel gives the lion’s share of attention to the two men with whom Midnight Cowboy originated as first a novel, then a film. He begins his story by intertwining the earlier lives and accomplishments of the novelist and playwright James Leo Herlihy, a specialist in melancholy grotesques in the Sherwood Anderson/Carson McCullers line whose 1965 book of the same name Midnight Cowboy was based on, and director Schlesinger. Herlihy grew up working-class in Detroit and Schlesinger came from a comfortably upper-middle-class Jewish family in the London suburbs. Both men were as openly gay as the times they lived through permitted, both had worked as actors, and both were at the height of their notoriety in the 1960s.

Frankel follows the two men through their formative years and rises to prominence that will lead to their eventual intersection: Herlihy had an intense mentor-mentee relationship with Anaïs Nin before gaining a foothold in the New York literary scene of the 1950s; Schlesinger spent his early career making BBC documentaries and successful British features, which would pave the way for him to adapt Herlihy’s book for his first American film. We get descriptions of queer bohemia in Manhattan and Key West, Herlihy’s second home; the gradual slackening of Hollywood self-censorship that would make a movie like Midnight Cowboy possible; and the crumbling economy and infrastructure of New York City under Mayor John Lindsay that would provide the movie its picturesque seedy backdrop. It was Lindsay’s office, too, that helped to facilitate location shooting in NYC, and thus a bumper crop of 1970s films that advertised its desolation to the world, issuing both a warning and an invitation.

Schlesinger began filming Midnight Cowboy in April of ’68, just as, Frankel writes, “nearly one thousand helmeted police officers emerged with clubs and blackjacks from blacked-out vans and buses and stormed the Columbia University campus to put a violent end to a weeklong sit-in by protestors there.” The turmoil of the era flares up on every side of Frankel’s narrative, from the Hard Hat Riots to Stonewall (of especial interest to Frankel is Midnight Cowboy’s role as a noteworthy step forward in queer representation in mainstream cinema). Some of the coincidences that Frankel brings in are irresistible, and give a sense of the period’s dizzying, sometimes terrifying eventfulness. In March 1970, a month before Midnight Cowboy’s triumph at the Academy Awards, Hoffman’s Greenwich Village home was damaged when bombs being prepared by members of the Weather Underground living next door exploded prematurely. The idea of the late ’60s in the US as a crashing and chaotic comedown is hardly novel, but the reputation is at least borne out by the headlines. Frankel recounts how Warhol superstar Viva, one of several Factory figures hired to populate the film’s “Witches’ Sabbath” party scene, was on the phone with Andy while getting her hair done for the movie when she heard Valerie Solanas enter with guns blazing.

Warhol, licking his wounds, is depicted as grumbling over what he perceived as an outsider incursion into his home turf: “I was so jealous. I thought, ‘Why didn’t they give us the money to do, say, Midnight Cowboy?’ We could have done it so real for them.” Frankel offers a rebuttal, writing that Schlesinger “didn’t want a movie about real male hustlers or a real psychedelic happening, just the appearance of each. And thanks in part to Warhol’s people, that’s exactly what they got.” (I’m not sure I understand the distinction, but I know that I prefer the existential presence of Joe Dallesandro to the fussy, tic-ridden performance of Dustin Hoffman.) The film’s credited editor, Brooklyn-born Hugh A. Robertson, the first African American member of the Motion Picture Editors Union, echoes Warhol’s view of Schlesinger and company as interlopers, calling the film “an Englishman’s view, not the real New York.” Schlesinger, clashing with Robertson, would eventually bring in his own cutter from the UK, Jim Clark, to work on the film’s snazzy flashback incursions, which include the gang rape of Buck and his girlfriend, played by Jennifer Salt, whose unhappy memory of her treatment during the shooting of that scene provides one of the more critical passages in what is otherwise an almost entirely valedictory volume.

Frankel, who has previously published histories of the making of both Fred Zinnemann’s 1952 High Noon and John Ford’s 1956 The Searchers, is diligent in his attention to all of the moving parts that go into making a film: the building of a team of disparate, sometimes at-odds talents; the days and weeks of preparation; the last-minute flashes of inspiration. He is somewhat less convincing in describing the why and how these many elements combine to create something of lasting resonance. We know that Midnight Cowboy is a “classic” because it shows up on AFI lists, and because it was a part of that ill-defined yet vaunted phenomena called “New Hollywood,” and because it won the Academy Award for Best Picture—going down in history as the only film with an X rating to do so. But while Frankel is free with superlatives—Voight is “transcendent,” and the pairing of Voight and Hoffman is “one of cinema’s greatest dramatic achievements”—he gives little sense of what recommends Midnight Cowboy to posterity beyond its alleged possession of a vagary like “compassion.”

As regards that X rating, it was self-imposed; as Frankel describes, the MPAA passed the movie with an R, but Arthur Krim, cochairman of United Artists, opted for the X after consulting with psychiatrist Aaron Stern, who advised that the film’s “homosexual frame of reference” ought to be kept away from developing adolescents. There had been recent real censorship battles over depictions of homosexuality in film—the 1964 police raid at a screening of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures springs to mind—but this doesn’t fall under Frankel’s purview. His attitude towards such “underground” activities is implicit in his description of Warhol’s movies as “excruciating avant-garde exercises” and “badly lit, out-of-focus, tedious home movies.” (In a discussion of the queering of cowboy iconography, Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys goes unmentioned.) If a figure of epochal significance like Warhol can come in for such a dismissive treatment, figures like Smith or Andy Milligan, whose 1965 Vapors depicted the cruising scene in the St. Marks Baths, don’t even bear footnoting.

Because Frankel looks at cinema for a reflection of the times and as a means for changing hearts and minds, he has a limited interest in fringe work. Addressed to a small and self-selecting audience, low-profile “underground” cinema has only so much capacity to “shift the dialogue” or have a “social impact”—the sorts of things the Academy has long gone in for, along with “brave performances,” “unlikely friendships,” “critiques of the American Dream,” and “cultured British directors.” This is why Midnight Cowboy’s victory really wasn’t so much of an outlier—from Joe and Ratso to Tony Lip and Don Shirley in Green Book (2018), you can draw a straight line that runs right through Park City, Utah. No less telling than Robertson’s “an Englishman’s view” is the tossed-off fact that Schlesinger, who’d tightened up the script in Malibu, had never been on the New York City subway prior to the beginning of location scouting for this film.

From Oscar triumph Frankel proceeds through a familiar threnody—the lament for Times Square, sanitized and Disneyfied, and for New Hollywood, struck down by Star Wars (1977), whose success, we’re told, would make things so much harder for “outsider” projects like Midnight Cowboy. It’s a nice enough tune, but after a while you might start to wonder how much of this mourning New Hollywood is another form of self-congratulation with the addition of dewy nostalgia, and how much a “breakthrough” like Midnight Cowboy amounts to the mainstream arriving at a point where real outsiders had been hanging out for years, and if there might not have been another New York City movie of the period more crucially in need of reappraisal. For example, something like Hal Ashby’s The Landlord (1970), also released by United Artists, which is among other things very cutting and funny on the subject of gentrification.

Nick Pinkerton is the author of Goodbye, Dragon Inn, to be published in March 2021 by Fireflies Press.