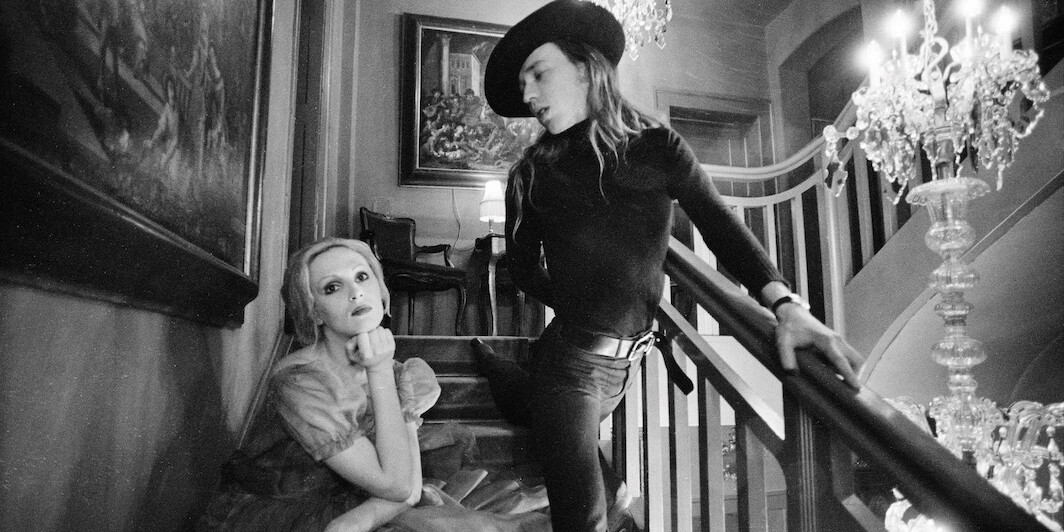

TO TRAVEL FROM Massapequa Park, a small town on Long Island, to Penn Station on the LIRR takes about an hour. It was a commute that Candy Darling made countless times between 1962, the year she turned eighteen, and 1974, the year she died, at age twenty-nine. The return trip from Manhattan—where she would first meet Jackie Curtis, Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Jane Fonda, Werner Schroeter, and so many other important collaborators and friends—often required Candy to travel under the cover of dark and to take a cab from the station directly to the Cape Cod house where her mom,

- print • Spring 2024

- print • Spring 2024

“IN THE BEGINNING God created the heaven and the earth.” You have to admit it’s a hell of an opening line. “When I think there was a day when a human first wrote those words,” Marilynne Robinson says, “I am filled with awe.” And that, for better and worse, is the kind of book Reading Genesis is—Robinson muses through Genesis, telling you what she thinks, getting filled with awe. It’s a book-length reading response. But it’s a reading response by Marilynne Robinson, who has written a few of the finest novels in English, so I’ll take it.

- print • Spring 2024

HER PLACE IN THE WINGS

- print • Spring 2024

THE LINGUIST ROSS PERLIN is an encyclopedist of New York City’s microworlds. In 2016, when he took me and ten others on a tour of Ridgewood, Queens, he alerted us to the presence of a dozen languages spoken in a two-square-mile radius, including Syriac, Yiddish, Malayalam, Haitian Creole, and Kichwa. He led us into an ancient, black-and-white-tiled, espresso-scented Sicilian social club, where a retired nonagenarian factory worker proudly discussed his dialect, Partanna. Later, we drank beer and ate bratwurst at the Gottscheer Hall, a tavern and cultural center for the Gottscheers, a tiny community of Germanic people who fled their

- print • Spring 2024

ALEXANDER POPE, WROTE NICHOLSON BAKER in a roaming 1995 essay about allegorical uses of the word “lumber,” was “one of the most skilled word-pickers and word-packers in literary history.” Across three erotic novels, seven non-erotic novels, four nonfiction books, two essay collections, and one work of autocriticism about John Updike, Baker has proved himself to be among the great picker-packers too, especially in the fertile, anything-grows orchards of figurative language. Similes, analogies, metaphors, and euphemisms are Baker’s uncontested territory. Few areas of knowledge have evaded his encyclopedic curiosity, which means he can compare a piece of machinery to another piece of

- print • Spring 2024

“LITERARY CRITICS do fulfill a very important role, but there seems to be a problem with much contemporary criticism,” Simon Leys once wrote. “One has the feeling that these critics do not really like literature—they do not enjoy reading.” This was a line my mind kept drifting to as I plodded through Lauren Oyler’s debut essay collection, No Judgment. The book was originally to be called Who Cares, and perhaps that title should have been retained. Who cares, really, about any of this? Gawker, the firing of Ben Mora, a TED Talk from 2010, Richard Brody’s New Yorker review of Tár,

- print • Spring 2024

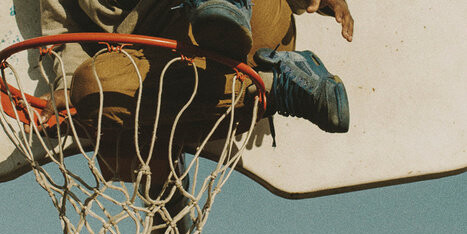

IN TODAY’S INSTALLMENT of “You’re Never Too Old to Learn,” it turns out that it’s not just its location that makes the state of Ohio the heartland of America. It’s also because, as its native son Hanif Abdurraqib writes in There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension, the seventeenth state of the Union is “shaped like a heart. A jagged heart. A heart with sharp edges. A heart as a weapon.” This disclosure, one in a torrent of observations, ruminations, and reveries tightly woven into the book’s narrative, gives you some idea of Abdurraqib’s willingness to pile everything he’s

- print • Spring 2024

SOMETIMES WHAT CONSERVATIVES SEEM TO FEAR MOST from liberals is not their money or their ideology but their judgment. Beneath the vast tide of right-wing grievance, there is a current of profound insecurity, a suspicion that liberals don’t think conservatives are good enough. There is nothing they desire more than the sight of a liberal humbled into seeing the light. To cater to this desire, the media has produced a peculiar new kind of pundit: the conservative who pretends to be a liberal—one agreeing, in spite of themselves, with the conservatives.

- print • Winter 2024

IT IS A FITTING IRONY that when trying to describe Anne Carson’s sensibility, one quickly hits the limits of language. To measure the breadth of her brain across her twenty or so books, one might acquiesce to hyphen-chic—as in, she is a poet-translator-scholar-of-ancient-Greek-essayist-visual-artist-playwright-maker-of-performances-and-dances—but such frantic stitching would fail to impart how seamlessly entwined her practices are. To distinguish her literary occupation from that of other authors, one might be tempted to conjure a new word via the dark arts of negation—she is an uncontainer of ideas, or she de-forms thought—but that would belittle her writing as merely an act of resistance

- print • Winter 2024

IN A 2014 INTERVIEW with Entropy Magazine, poet-filmmaker-scholar-anarcho-feminist-writer and dreamer Jackie Wang apologetically names a “piece of art that has recently undone/inspired you” as Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac. “What was it that made me receptive?” she wonders. “I don’t want to credit Lars von Trier!” Wang’s ALIEN DAUGHTERS WALK INTO THE SUN: AN ALMANAC OF EXTREME GIRLHOOD (Semiotext(e), $18) is perhaps not strictly an “art book,” but I make no apologies for selecting it, and I do want to credit Jackie Wang. Modestly illustrated with doodles, some black-and-white film stills, and stray photo nuggets, the book is no “sumptuous” display-case feat

- print • Winter 2024

THE FIRST THING I NOTICED about 1962’s Cléo from 5 to 7, one of the more enduring hits from filmmaker and artist Agnès Varda, is that the run time is not two hours but ninety minutes. Where did those thirty minutes go? How did she make a “real-time” film that doesn’t execute its promise? I always neglect to keep tabs on that missing half hour; I’m enjoying the film too much. Such is Varda’s slippery genius. She creates a structure, then leaves just enough room to show you how she did it—if you know how to see it. Varda knew all

- print • Winter 2024

AT THE BEGINNING OF DECEMBER, music-streaming behemoth Spotify laid off 1,500 employees. It was its third set of axings last year in response to the tightening of capital markets, altogether adding up to more than a quarter of its global staff. But this round was different, because it included Glenn McDonald.

- print • Winter 2024

MIDWAY THROUGH ABOUT ED, Robert Glück revives a line by Frank O’Hara: “Is the earth as full as life was full, of them?” Referring to three of O’Hara’s recently deceased friends, the line appears in “A Step Away from Them,” where it clangs against the rest of the poem and its meandering attention to noontime activity in midtown Manhattan, 1956. It perplexes Glück, whose About Ed remembers Ed Aulerich-Sugai, a lover and friend who died of AIDS-related complications in 1994. “The misdirection threw me,” Glück writes, “from the earth being full, to life being full, instead of Ed being full

- print • Winter 2024

IN THE POEM “POST,” from her posthumously published collection, The Cipher, Molly Brodak writes:

- print • Winter 2024

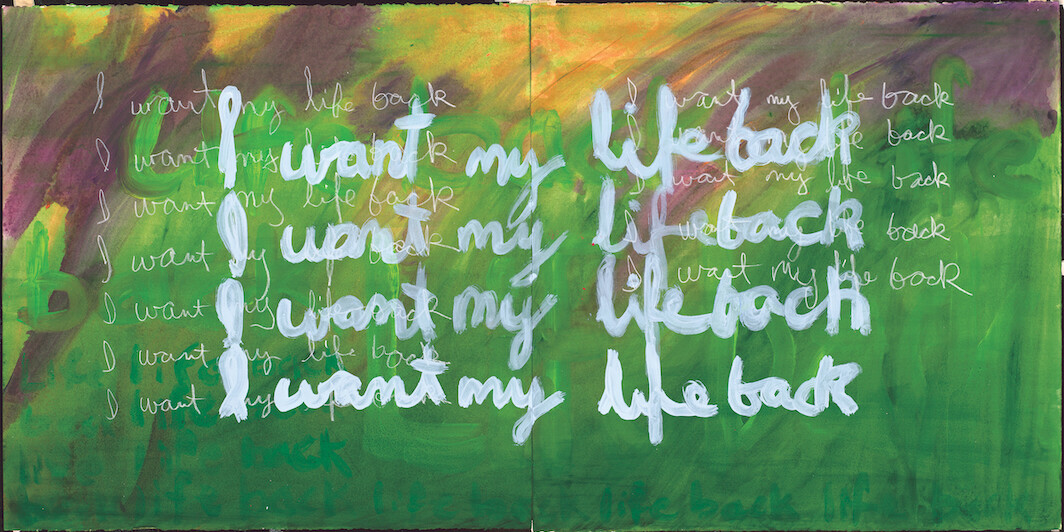

THIS IS ONLY AN OPINION, BUT: no one should make art about their divorce until they’ve experienced at least one heartbreak after the marriage’s end. I keep an inventory of all the times I encounter an artist who manages, in telling a story about a divorce, to also include the story of another breakup that followed the supposedly definitive one. I love to see anything that complicates more straightforward accounts of life after divorce. That next heartbreak—the more devastating, the better—must be reckoned with, because it dispels any remaining illusions, or maybe delusions, about what one is capable of in

- print • Winter 2024

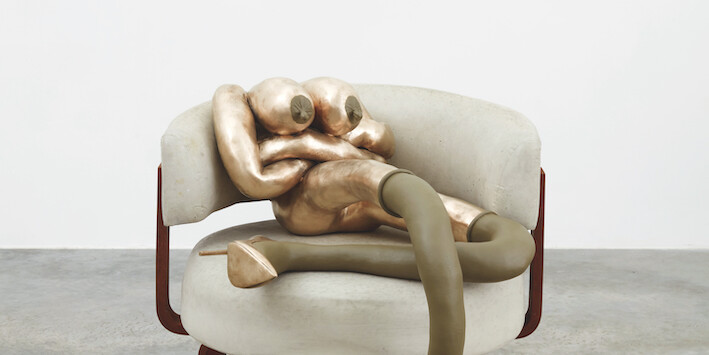

Sarah Lucas, CROSS DORIS, 2019, concrete, bronze, steel, iron, and acrylic paint, 28 1/8 × 28 3/4 × 26 3/4″. Image: Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas. ARE WE ALLOWED TO ENJOY THIS? Chicks and dicks, fags and chicken thighs? Sarah Lucas’s sculptures use corner-store staples—bananas, cigarettes, a […]

- print • Winter 2024

IF, AS CLAUDE LÉVI-STRAUSS PROPOSED, “the purpose of myth is to provide a logical model capable of overcoming a contradiction,” then the act of keeping a diary, that practice of private self-mythology, is at least partially an attempt to overcome the contradictions inherent in a self. Granted, there’s a raft of differences between myths passed down over eons and those made about oneself within the span of a single life. The myth of Icarus, for instance, has survived due to its decisive ending and moral weight. But self-mythology—whether in the form of a journal, internet persona, or daydreaming—is a molten

- print • Winter 2024

WHAT IS AN AUTHOR? A conduit for the divine or a poor schlub combining and recombining stale units of meaning? Both answers share the assumption that a literary work is the product of one consciousness. This assumption is a kind of spell: even a book’s acknowledgments, where the many other hands that went into its making come into view, or its publisher’s colophon, which advertises the institutional infrastructure behind the text, cannot totally ward it off.

- print • Winter 2024

Mulligan’s pub, Joyce cat, from Evelyn Hofer: Dublin (Steidl, 2023). © 2022 Estate of Evelyn Hofer. “I’M NOT EVEN INTERESTED IN MOMENTS.” The German photographer Evelyn Hofer (1922–2009) knew her aesthetic was in some ways at odds with her time; her postwar streets and squares are emphatically not in the style of Henri Cartier-Bresson and […]

- print • Winter 2024

WILLA CATHER WAS A MASTER OF BEGINNINGS. O Pioneers! (1913), her first novel after the false start of Alexander’s Bridge (1912), opens on a provocatively odd note: “One January day, thirty years ago, the little town of Hanover, anchored on a windy Nebraska tableland, was trying not to be blown away.” Soon the attention shifts to the “cluster of low drab buildings huddled on the gray prairie, under a gray sky . . . set about haphazard on the tough prairie sod; some of them looked as if they had been moved in overnight, and others as if they were

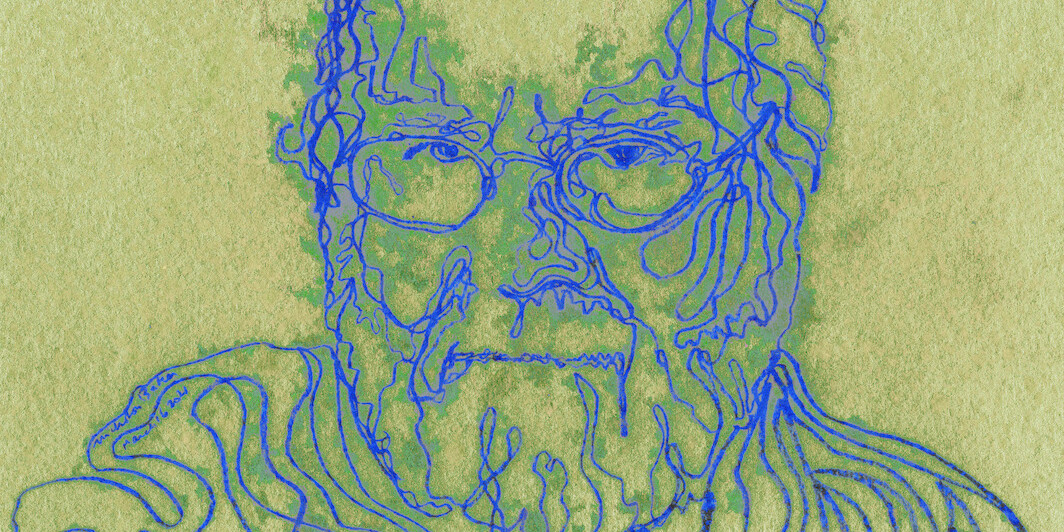

![*Rembrandt, _The Angel preventing Abraham from sacrificing his son, Isaac_, ca.1634-35,* chalk and wash on paper, 7 3/4" × 5 3/4". Image: Wikicommons/The British Museum [[PD-US]].](https://images.bookforum.com/uploads/upload.000/id25349/featured00_landscape.jpg)