IF THE MEASURE of a debut is how capably it shits on the pieties of its literary forebears, then Honor Levy’s funny, provocative My First Book is an unqualified success. The fact that I, an Elder Millennial, found it largely inscrutable proves the point.

Though nominally fiction—at least according to the metadata—the sixteen pieces collected here could as easily be called prose poems, personal essays, or rants, though their author would likely find all of these classifications “cringe.” The book opens with “Love Story,” which details the online courtship between a guy in his “fall of Rome era” and a young woman “giving damsel in distress.” Sample sentence: “He was kamikaze mode, pumping iron, all Sun and Steel sending hearts <3 <3 <3 to his Saint Wilgefortis, darling, starving, hily hikikomori virgin femcel holed up in her Serial Experiments Laincore bedroom.” Still with me?

Not everything in My First Book has such a high barrier of entry. “Good Boys,” a vignette about young people smoking on a Paris rooftop, recalls the early work of Levy’s fellow Bennington College alum Bret Easton Ellis. Like Ellis, Levy achieved notoriety at a young age for both her writing and her public persona; the New Yorker published “Good Boys” when she was twenty-one, and the New York Times, The Cut, and Vanity Fair have anointed her a “darling” and “It Girl” of the downtown scene, a loose coterie of artists and writers who coalesced around the Lower East Side’s quasi-mythical Dimes Square during the pandemic to snort ketamine, stage amateur theater, say “retard”with impunity, and con PayPal founder Peter Thiel into funding small-circulation literary journals—or so it’s been said. Until recently, Levy cohosted Wet Brain, a self-described “post-canceled” podcast that gave airtime to heterodox thinkers such as the neo-feudalist start-up founder Curtis Yarvin and the novelist-turned-raw-milk-evangelist Tao Lin. Levy’s cohost, Walter Pearce, has described her as a “Quirked Howard Stern.”

Thankfully, despite her entrenchment in it, Levy has little interest in writing about the downtown scene, a subject that has received more than its share of spilled ink already. In fact, “Good Boys” is one of the few pieces in My First Book with a primarily offline setting. Elsewhere, we follow Levy’s alter egos Sad Girl and Internet Girl through the looking glass of their LCD screens:

When I was eleven it was spelled with a Big I. That was how I was taught it. How autocorrect corrected it. Like god to God. It was a place to visit. A proper noun. The Internet. The thinspo forums and videos of Saddam’s execution and the pics from that bat mitzvah I wasn’t invited to. I could go there and I went there that day after school on my clunky white laptop. I went there and I never came back. . . . It was like coming a long way through a dark tunnel and turning around to look at the speck of light from which I came, but there was no light. . . . The tunnel was and always will be my world.

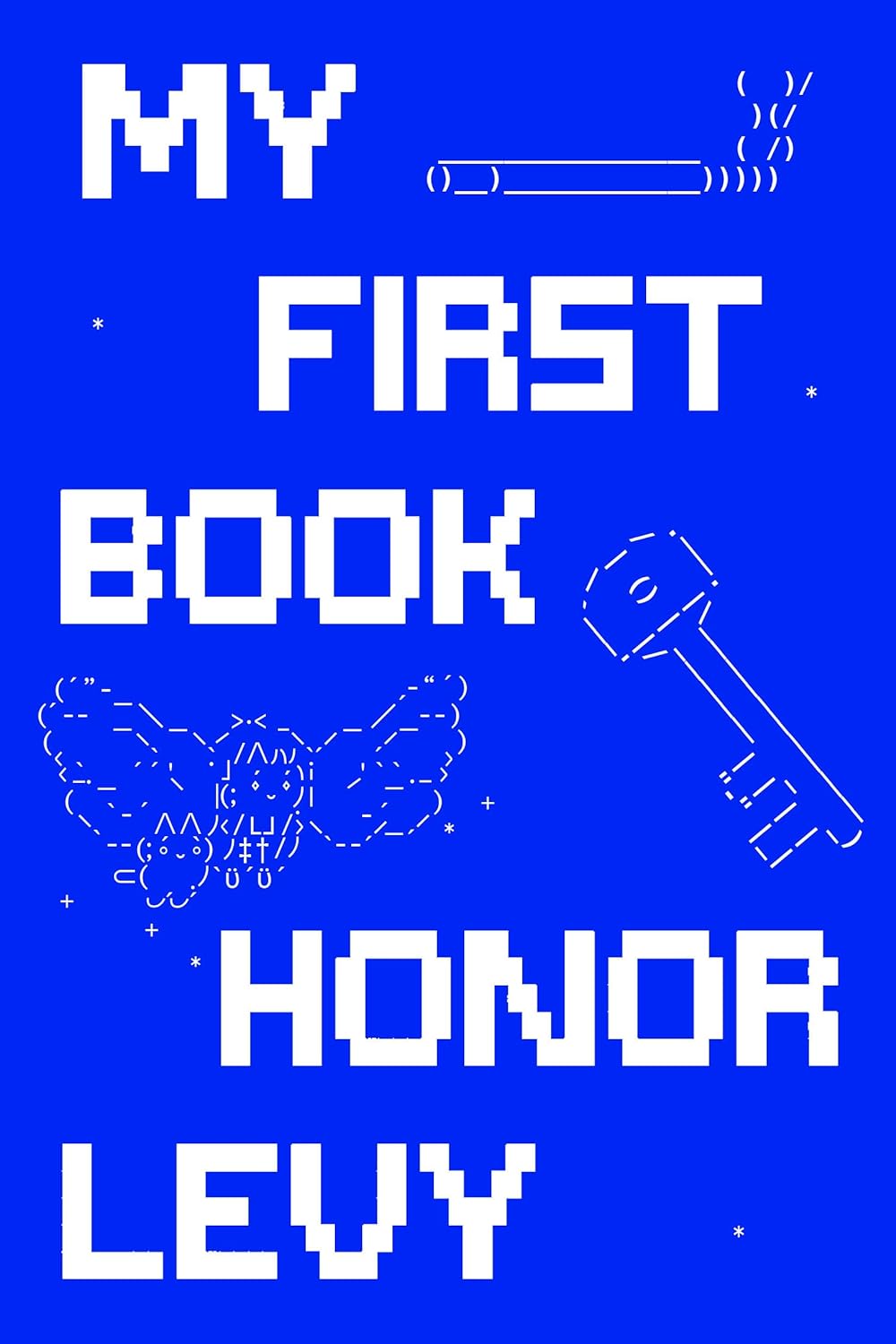

As this passage makes clear, Levy’s work isn’t about the internet so much as it’s sprung from a consciousness so shaped by the internet that no imaginative act exists beyond its influence. Each story in My First Book opens with ASCII art on its title page, and some include “links” to sites such as honor.baby/lovestory, a small repository of curated content including a sped-up version of MGMT’s “Little Dark Ages” and a time-lapse GIF of a rotting fox. Almost all are written in present tense, and time is nonlinear, often jumping between decades from one sentence to the next: “I’m twenty-one. I’m eleven. I’m on the internet. I’m twenty-one.”

For her “normie” readers, Levy has graciously included “Z was for Zoomer,” a fifty-six-page glossary beginning with “Autism,” which apparently afflicts “all the hot-art-world-adjacent millennial girls.” Later, under “Edgelord,” she cites the glossary’s “Autism” entry as an example of “a total edgelord move.” As in Douglas Coupland’s 1991 novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, in which quickly outdated neologisms like “ethnomagnetism” were defined in the margins, Levy’s glossary points to the mutability of language and to the fundamental impossibility of catching a zeitgeist, especially one that moves at 5G speed, and freezing it in the amber of the printed page. Note the past tense in the piece’s title, and in her introduction to it: “These are some words that briefly built a world I briefly lived in.”

Levy, of course, is not the first writer to try to capture the texture of a tap and scroll existence; Patricia Lockwood, Joshua Cohen, and Mark Doten have explored similar territory in recent work. But Levy is more than a decade younger than these writers, a generation gap that’s felt in her command of Gen Z vernacular and also in her restlessness. Often, Levy starts off in the ballpark of the traditional short story—i.e., the kind with characters and scenes—and then digresses and never returns, leaving the initial frame of narrative open like a forgotten browser tab. “Hall of Mirrors” begins with an after-school teacher letting a child sit on her lap—she’s entranced by the boy’s “anime blue eyes”—but quickly veers into a passage that reads like a Wikipedia entry on the history of mirrors, which leads to a didactic riff on the dangers of PFOAS—The End. Other pieces don’t even bother with the pretense of a frame. “Brief Interview with a Beautiful Boy,” the title of which nods to David Foster Wallace, isn’t a story so much as a pile of declarative statements: “He’s drunk as fuck and maxing out his credit cards. He’s trying not to scare the hoes, but it’s hard. He’s a spoiled brat. He absolutely despises liberals. He can’t even do a single pushup.”

On Wet Brain, Levy frequently contended that there’s no longer a difference between irony and sincerity, “based” and “cringe.” Asserting this may be another edgelord move, but to her point, it isn’t only an edgelord move. Just as these “crazy unprecedented beginning and end times” have blurred the borders between on- and offline, and between avatar and self, Levy seems to be suggesting that language has become so debased and inescapably referential that there’s no longer such a thing as single-entendre speech. Her story “Cancel Me” begins: “It’s 2019. Max is canceled. Oliver is canceled. Kian is canceled. Rob is canceled. Bryce is canceled. Carter is canceled.” Each repetition dilutes meaning until no meaning remains.

By her own definition, this worldview would make Levy a “Doomer,” someone who’s swallowed a “catastrophic black capsule of apathy, denial, nihilism, fatalism, and defeatism.” There are moments of glib humor in My First Book that support this conclusion, such as a joke about teen girls wanting to be “Dachau liberation day–skinny.” But herstrongest stories find Levy attempting to peel back the layers of irony in search of something buried beneath them.

In his 2017 n+1 “In Memoriam” for Denis Johnson, the writer Justin Taylor squares the bleakness of Johnson’s fiction with the author’s Christian faith by suggesting that, for Johnson, “evil is a symptom of suffering, which is to say estrangement from the sacred.” I’d imagine that Levy, an “ethnically Jewish” convert to Catholicism, would concur. The difference is the tenderness with which Johnson treats the sinners and losers who populate his work. As Taylor writes, “He does not damn his souls to stay lost. He believes in the possibility, perhaps the promise, of their redemption.” I kept looking for a similar tenderness—and a similar promise—in My First Book. Occasionally I found it, such as in “Cancel Me,” when the narrator looks across the room at a party and “can see everyone holding their Red Solo cups and hurting.” A small moment of empathy, it sticks out in a collection whose author’s default stance is a gently sardonic sneer.

But maybe empathy’s the wrong thing to look for in this kind of book; certainly Johnson is the wrong point of reference. A better one might be the experimental novelist Mark Leyner, a ’90s cult figure now largely remembered as the primary target of “E UNIBUS PLURAM,” David Foster Wallace’s 1990 polemic on television’s deleterious influence on American fiction.

While Wallace concedes that Leyner is “dazzlingly creative” and “extremely funny,” he scolds Leyner’s “amphetaminic eagerness to wow the reader” and concludes that his work is ultimately “doomed to shallowness by a desire to ridicule a TV culture whose mockery of itself and all value absorbs all ridicule.” As readers of Infinite Jest are aware, Wallace had a tortured relationship with the concept of “entertainment,” and I’ve always taken his assault on Leyner as a projection of anxiety over his own reader-wowing pyrotechnics. Regardless, it’s a fundamental misreading of Leyner’s project—which was not to ridicule TV culture but to radically repurpose sitcom clichés and ad-speak into something ecstatic and alive. I’m wary of similarly misreading Levy. Despite her insistence that “everything’s a copy so let me paste from Wikipedia,” the stylized eccentricity of her best work reads like an act of resistance against the algorithm’s assault on the imagination. If she sometimes resigns herself to the futility of that resistance, who can blame her? These are bleak times. A bromide from the early days of social media was that you had to separate the static from the noise. A generation later, My First Book exposes the fallacy of such a distinction. It’s all static. It’s all noise.

Adam Wilson is the author of three books, most recently the novel Sensation Machines (Soho, 2020).