“Certain absences are so stressed, so ornate, so planned, they call attention to themselves; arrest us with intentionality and purpose”—so said a tenebrous Toni Morrison in a 1988 speech at the University of Michigan. It was a canny, candid pronouncement: Morrison had registered a horripilating chill in the body of American literature, the presence of a ghost passing through—that of the Afro-American. A muted, neglected specter, she said, it stalked the canon in a close orbit, reputed not to exist. Her genius was to listen for it, to log the whispers of its alternate and unsanctioned histories. What she heard

- print • Dec/Jan 2020

- print • Dec/Jan 2020

“These things happened, but not as described.” So begins The Baudelaire Fractal, the vertiginous debut novel by poet, translator, essayist, and most genteel of insurgents Lisa Robertson. Like her previous books, her latest is a work of buoyant loveliness and muscular erudition, a lush thicket of thoughts that here enrich the ease and breeziness of personal narrative with the chewier textures of history, criticism, and literary theory. “Writing unfolds like a game called ‘I,’” declares the novel’s diaphanous narrator, behind whom Robertson herself lurks, and to whom she gives the name—the I color—Hazel Brown. Lovingly sported by Robertson like a

- print • Dec/Jan 2020

Octogenarian, slight, and frizzy-haired, Sonallah Ibrahim is a bit of a grump. For over five decades, the Egyptian novelist has served as the Arab world’s preeminent bard of dashed hope and disillusionment. His oracular if gloom-filled books are blinding inventories of consumerism, degradation, dictatorship, stagnation, pleasureless sex, creeping Islamism, and mind-numbing Americanization. To be alive and conscious, suggests Ibrahim, is to be humiliated. He lives in Cairo, the city of his birth and the mother of endless annoyance. “I’m so irritated most of the time by the dirt, the noise, and the commotion, but nevertheless I find that I can’t

- print • Dec/Jan 2020

In 2008, Gary Lutz gave a lecture called “The Sentence Is a Lonely Place,” a transcript of which was later published in The Believer. The lecture outlined Lutz’s approach to short stories, specifically his punctilious focus on the sonic qualities of the sentence. He spoke in favor of “steep verbal topography, narratives in which the sentence is a complete, portable solitude, a minute immediacy of consummated language—the sort of sentence that, even when liberated from its receiving context, impresses itself upon the eye and the ear as a totality, an omnitude, unto itself.” Interest in The Complete Gary Lutz, a

- review • November 21, 2019

Here in the United States, we are quite obsessed with stuff. We buy new cars, weighted blankets, statement sneakers, the latest iPhone. Amazon Prime delivers 1.5 million packages per day in New York alone. The things we own have become part of our identity, marking not only our tastes and values, but our sophistication and class aspirations. But imagine what would happen if, one by one, those items began to disappear, not just from our physical lives but from our collective consciousness as well. Who exactly are we without our things and the memories that come with them?

- print • Dec/Jan 2020

I missed Guillaume Nicloux’s film The Kidnapping of Michel Houellebecq on its release in 2014. What a mistake—it’s a real hoot! Nicloux’s deadpan mock thriller tacks from a rumor that the author had been kidnapped “by Al-Qaeda (or aliens)” during the book tour for his 2010 novel The Map and the Territory. (I watched it on Google Play, which mislabels it a “documentary”—much of it does seem to be improvised, and Houellebecq does seem to be speaking as himself, but credit Nicloux for the devious scenario and execution.) We see Houellebecq’s routine—smoking on the street and bumping into friends, smoking

- review • November 12, 2019

At the beginning of Lara Williams’s Supper Club, we find the narrator Roberta stuck in a typical millennial holding pattern. As she enters her late twenties, Roberta is working an uninspiring assistant job. She spends her free time cooking a lot, socializing very little, and dating never. Flashbacks to Roberta’s college days present her as similarly meek—she rarely ventures off-campus, feels bored by her major, and wonders how to interact with her roommates. Then as now, she makes little effort to shift her circumstances.

- review • October 17, 2019

Of the emotional afflictions we witness in those around us, obsession may be the most discomfiting. It’s also the most gendered: We’re conditioned to find it appealing, flattering when a man is the obsessed—Calvin Klein’s women’s fragrance “Obsession,” is, I assume, designed to elicit obsession from males who pass within smelling range of the female wearer, after all. But an obsessed woman? It’s likely people find her pathetic. In the case of Adam Foulds’s recent novel Dream Sequence, we see obsession engulf Kristin, a lonely divorcée who spends her time holed up in her TV room watching The Grange.

- review • October 15, 2019

Early in Middlemarch, George Eliot’s young heroine finds herself alone on her honeymoon, bewildered by her disappointment in her new marriage. After describing Dorothea’s desolation, the narrator addresses the reader directly:

- review • October 8, 2019

History, Tolstoy insisted, is not driven by great men—the Bismarcks, the Napoleons of this world. It is constructed from an endless number of minute details, like drops of water, or grains of sand.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

The erstwhile wunderkind has been coping with the onset of middle age for four books now. The novels NW (2012) and Swing Time (2016) were about the ways youth slips away, among other things: friendship, neighborhood loyalties, class, celebrity, violence, inequality, biracial identity, sex, the internet, Africa, England, and how to write a novel when realism is anxious about its own survival. The essays in Feel Free (2018) and now the stories in Grand Union have taken in parenthood, the passing of the older generation, unexpected political upheavals, unwelcome physical transformations, and the arrival of a strange species: people in

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

At the midpoint of D. H. Lawrence’s Women in Love occurs one of the really extraordinary hidden scenes in English literature. Ursula and Gudrun are the young protagonists, figuring out their ambitions, their loves, and their futures. They are walking to a neighborhood water-party, with their father and mother in front of them, when suddenly they burst out in mockery. “‘Look at the young couple in front,’ said Gudrun calmly. . . . The two girls stood in the road and laughed till the tears ran down their faces, as they caught sight again of the shy, unworldly couple of

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

We all know that men don’t understand women. How could they? Women spend the whole time trying to understand themselves. “I specialize in women,” the writer Nancy Hale said in 1942. “Women puzzle me.” Hale felt that she knew how, “in a given situation, a man [was] apt to react.” (She’d been married three times by the age of thirty-four.) Women, on the other hand, vexed and intrigued her. Her mother, the portraitist Lilian Westcott Hale, made a career of looking at other women, including her daughter. In The Life in the Studio (1969), a memoir about growing up with

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

On October 17, 1973, Ingeborg Bachmann—the Austrian poet, novelist, librettist, and essayist—succumbed to burns sustained three weeks prior when she, tranquilizers swallowed and cigarette in hand, lay down to sleep and inadvertently lit her nightgown and bed on fire. She was forty-seven and had, since receiving the Gruppe 47 prize even before the 1953 publication of her first poetry collection, Borrowed Time, astonished the German-speaking public as well as esteemed peers with texts that pushed against tradition and played at the limits of language. She awed the likes of Günter Grass, Peter Handke, Uwe Johnson, Fleur Jaeggy, Elfriede Jelinek, and

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

In the eight years since a small group of anti-capitalist activists set up camp in Zuccotti Park, Occupy Wall Street has generated its own literary subgenre: Jonathan Lethem’s Dissident Gardens, Ben Lerner’s 10:04, Eugene Lim’s Dear Cyborgs, and Ling Ma’s Severance all feature scenes of the 2011 protests. In these novels, the Occupy movement, with its non-programmatic political aims and nonviolent tactics, represents a particularly utopian way of thinking about contemporary revolution—one that is less about direct action than it is about nonaction, about indirection.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

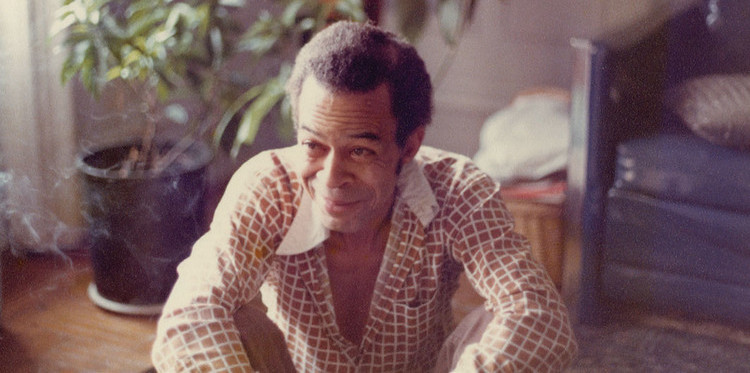

The decades of near-silence that came in the wake of Charles Wright’s trilogy of short novels seem almost as aberrant and disquieting as the novels themselves. Wright died of heart failure at age seventy-six in October 2008, one month before Barack Obama’s election and thirty-five years after the publication of Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, the last of Wright’s novels, whose 1973 appearance came a decade after his debut, The Messenger. Wright clawed and strained from the margins of American existence for widespread acknowledgment, if not the fame his talent deserved. Cult-hood was the best he got, but it’s

- excerpt • August 22, 2019

“Little Women was about the best book I ever read.” So began my fourth-grade book report, in 1981. Clear, if uninspired. After one-and-a-half double-spaced pages of cursive rhapsodizing in support of this daring claim, I concluded with the lazy feint of an already overburdened critic: “I would like to go on and on with this report but it would be longer than the book, so if you want to find the rest out my opinion is to read it.”

- review • August 13, 2019

The year is 1927. A schoolteacher who twenty-three years ago showed up with a bicycle and a duffel bag in Thyregod, Denmark, has just lost her husband. Vigand was a cold, pretentious doctor. Once, he could barely be bothered to make a house call on a man who had swallowed his dentures. Vigand knew he was dying. He drove himself to the hospital. He checked himself in, wearing his new gray suit. He told none of this to his wife, twenty years younger and ten times warmer.

- review • August 7, 2019

Today’s challenges of transparency and opacity in everything from the personal to the institutional have created a desire to experience these qualities afresh in literature. I have often thought of these issues as lake-like, because lakes are eerily both. It is a psychic challenge to imagine what cold, still pools of water withhold below a calm, shimmering surface. The work of the Swiss writer Fleur Jaeggy is similarly lacustrine, typified by cool observations that quickly plunge into uncertain depths. Sweet Days of Discipline, set in the 1950s at an elite girls’ boarding school in Switzerland near the Alpine waters of

- review • July 24, 2019

The question that arises whenever a novel is reissued is “why now?” In the case of Suzette Haden Elgin’s Native Tongue, republished by the Feminist Press this month, the answer is evident: First published in 1984—one year before Margaret Atwood’s similarly dystopic The Handmaid’s Tale—Native Tongue is, depressingly, still extremely relevant.