A DECADE AND A HALF AGO, a book so enchanted me that it was hard to pull away. If I were to get any of my own work done, I needed to hide it. (The book was very long, over eight hundred pages; I didn’t have the time.) But the tome kept jumping back into my hands. I could have given it away, of course, or simply tossed the thing, but surely at some point—when this oppressive spell of work was over—I’d want to dive back in. I had only finished a third, perhaps less. One day, I came across

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

THE LIFE OF THE MIND, Christine Smallwood’s debut novel, begins with an ending. We meet Dorothy, a contingent faculty member in the English department where she used to be a doctoral student, as she negotiates the miscarriage of an accidental pregnancy. The pregnancy, at once unexpected and welcome, is a blighted ovum, “just tissue” according to her ob-gyn. The metaphor is clear: Dorothy’s academic career and the pregnancy are both projects of development and growth that never had a chance to thrive.

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

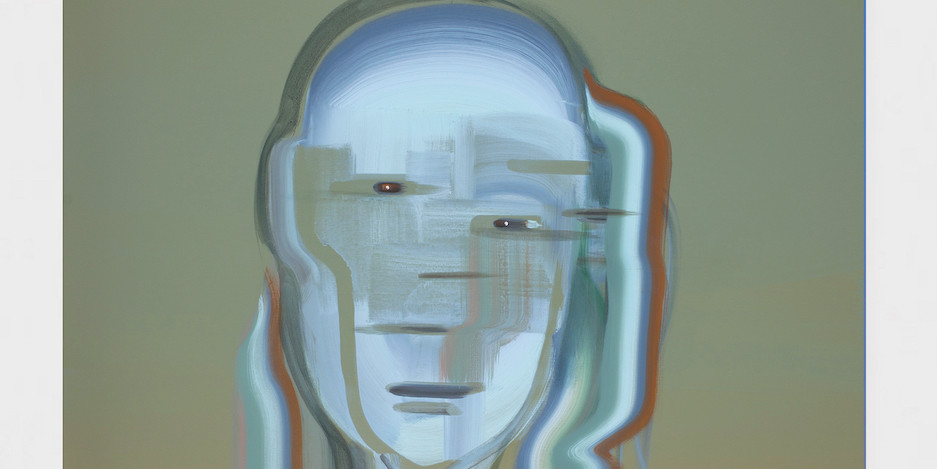

KLARA, THE TITLE CHARACTER OF KAZUO ISHIGURO’S new novel, would seem to have some serious shortcomings as a narrator. Introduced in a retail outlet in an unnamed city where she alternates between the window and less desirable display positions, Klara is a solar-powered AF, or Artificial Friend, who exists solely to assist and accompany the human child who purchases her. Despite her impressive capacity for mimesis and spongelike powers of absorption, we never forget Klara’s obvious limitations. Her view of the world is circumscribed, her vocabulary stilted, her agency virtually nonexistent. All of which make her an oddly perfect fit

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

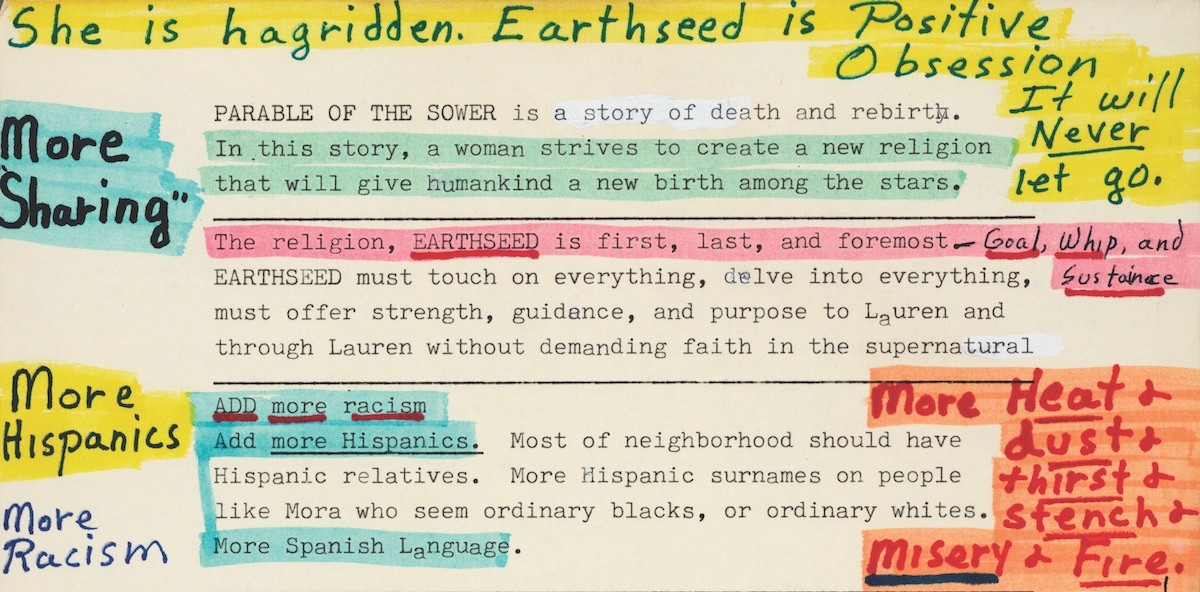

ONE DAY IN 1960, when she was thirteen, Octavia E. Butler told her aunt that she wanted to be a writer when she grew up. She was sitting at her aunt’s kitchen table, watching her cook. “Do you?” her aunt responded. “Well, that’s nice, but you’ll have to get a job, too.” Butler insisted she would write full time. “Honey,” her aunt sighed, “Negroes can’t be writers.”

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

TORREY PETERS HAS BEEN self-publishing and giving away her stories online for pay-what-you-like prices since the mid-2010s. In the short works The Masker, Glamour Boutique, and Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones—a sci-fi contagion story about hormones—Peters zeroes in on moments when her trans protagonist behaves or thinks in ways that communal consensus has agreed is “wrong.” Peters simplifies nothing, explains nothing to the outsider, which is why she is treasured by readers who are also protective of her and her work. For as long as such stories have stayed in the underground, where people make an effort to understand

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

THE FIRST HALF of Patricia Lockwood’s novel No One Is Talking About This opens in a place between life and death. The second half unfolds in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. The first half is about the internet. The second half is about having a body in a world. These halves are as discrete as a clunky little screen glowing its gloamish light into an open face, two limitless modes that find their limit only where they merge. The novel takes shape in the parenthetical scoop of a Venn diagram between machine and mind, crowd and solitude, joke and beauty.

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2021

THE UNNAMED NARRATOR of Lauren Oyler’s debut novel is an ex-blogger. She delivers hard truths about what she reads online: popular tweets and think-pieces alike are “aimed not at clawing for some difficult specificity but at reaffirming a widespread but superficial understanding.” Fake Accounts details her pivot to clawing, and to fiction; she is writing a semiautobiographical novel of hyperspecific circumstances, having recently discovered that her boyfriend, Felix, peddles anti-Semitic conspiracy theories via Instagram. Soon after, he dies. She gets the news at the Women’s March in Washington, DC, where she’s been biding her time at the dawn of the

- excerpt • January 21, 2021

I thought that in the interest of financial stability Nanae ought to increase her hours of part-time work rather than stocking up on lottery tickets.

- review • January 12, 2021

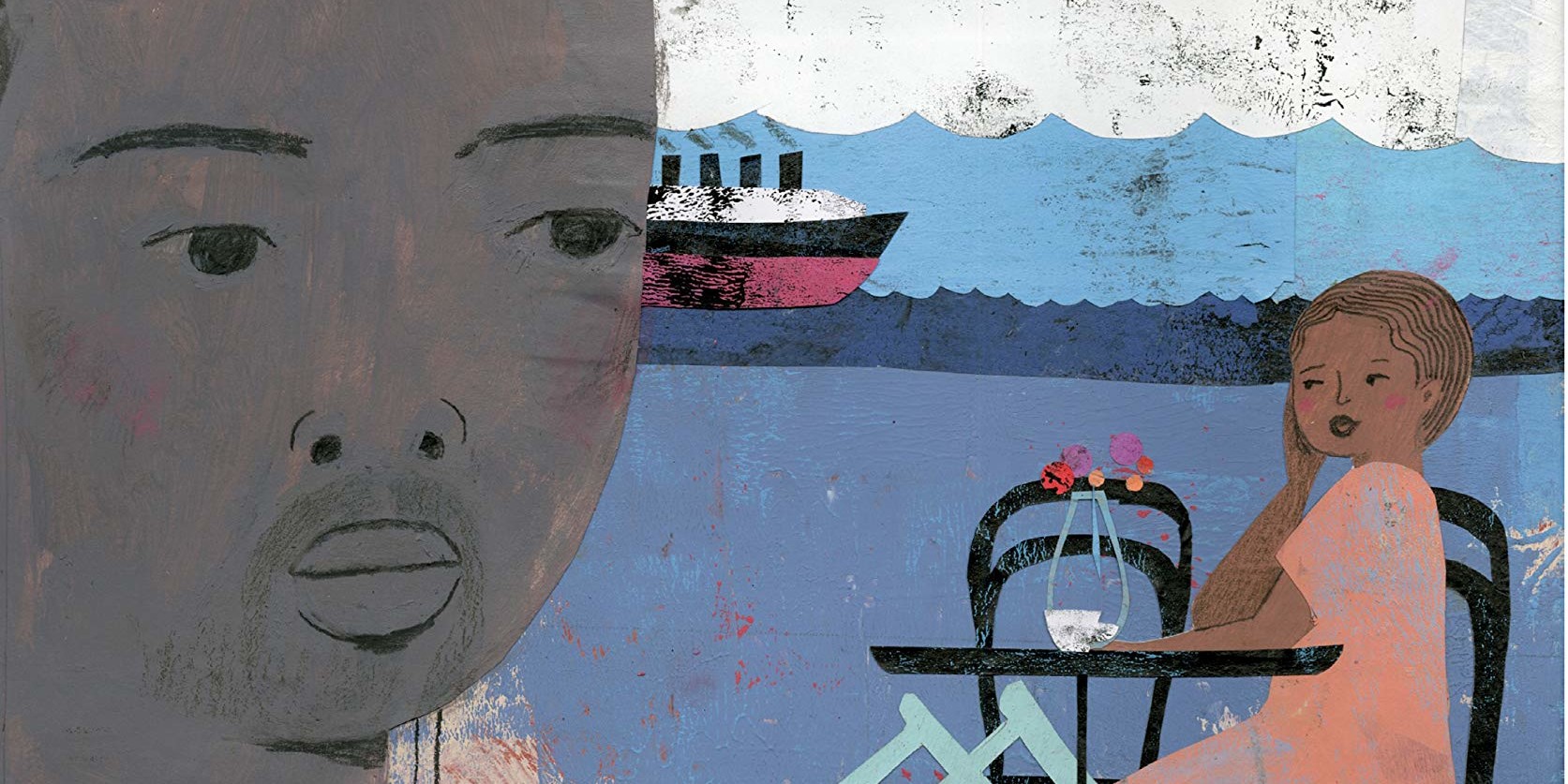

Claude McKay’s “lost” novel Romance in Marseille begins where most novels would end: with a twist of fate that brings life to a grinding halt. Lafala, a West African sailor and a man of “shining blue blackness,” is discovered stowing away on a ship traveling from Marseille to New York and detained in an uninsulated bathroom, where he nearly freezes to death. When he comes to, he’s in a New York hospital, legless. Lafala’s first reaction is fear: he has heard that doctors in hospitals sometimes kill Black patients to use as cadavers. This is not merely superstition, but the

- review • December 15, 2020

For every novel David Mitchell writes, two are published: there is the novel read by Mitchell’s fans, and the novel read by first-timers. Each of his books stands alone, as a thoughtful, researched, realistic portrayal of a specific time or place. There is a coming-of-age novel about a video-game obsessed adolescent in present-day Japan (Number9Dream), a novel about a Dutch visitor to a port near Nagasaki at the very end of the eighteenth century (The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet), a novel that deals with a widespread environmental collapse and the horror it brings to ill people (The Bone

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2021

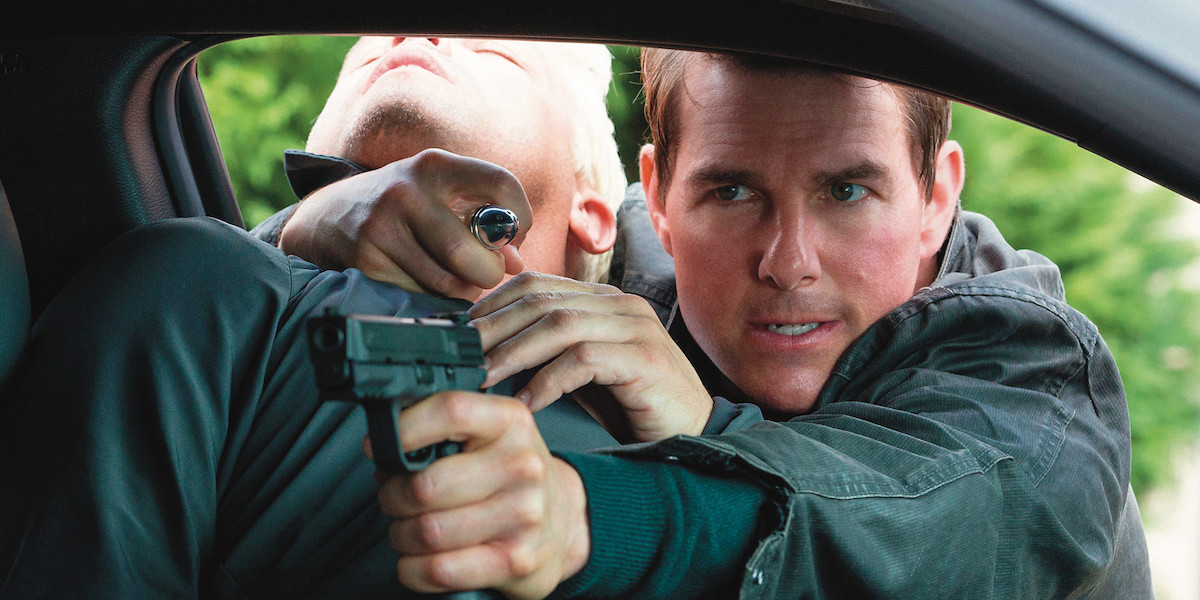

YOU KNOW HOW, when you roll into a small town for the first time, in search of a slice of pie and a decent cup of coffee, you inevitably uncover a byzantine and nefarious criminal conspiracy, perhaps concerning Russian spies and Nazis? And your sense of justice and your MMA-style fighting skills demand that you stick around long enough to expose the evildoers, protect the innocent, and kick a whole lot of ass?

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2021

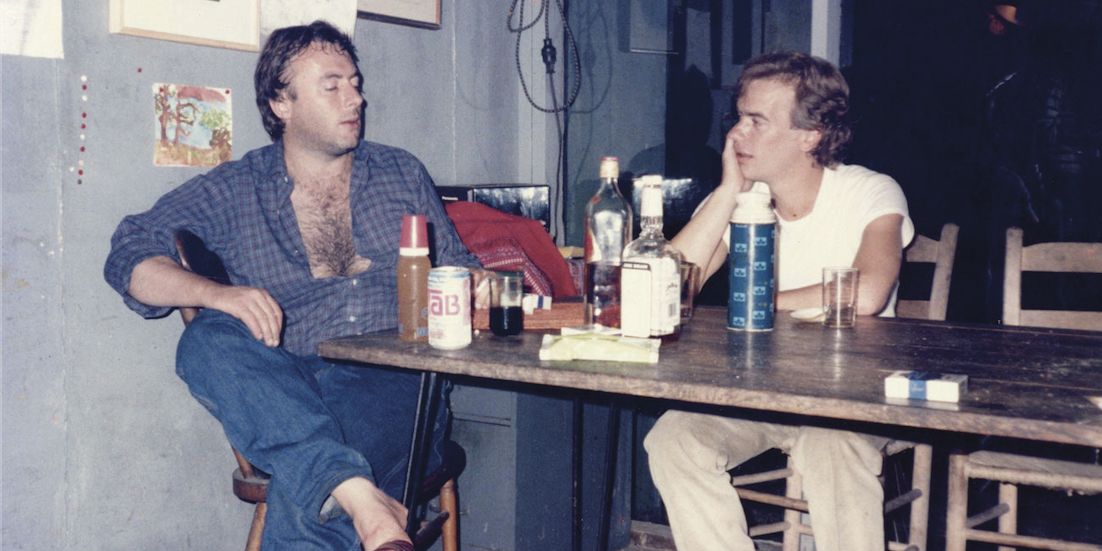

IN 1975, BREECE D’J PANCAKE was a twenty-three-year-old English teacher at Staunton Military Academy in the Shenandoah Valley. He was half a day’s drive from Milton, West Virginia, where he’d grown up. He hated the brutal, stultifying culture of the school, but the job was enough to support himself as long as he lived cheaply, which was important because his father had multiple sclerosis and could no longer work. His parents, Helen and C. R., said they were getting by, but he worried about their long-term financial security. Pancake was a loner, a dreamer, a contrarian, a depressive—in short, a

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2021

IN HIS THIRTEEN-LINE POEM “Scotland,” the Scottish poet Alastair Reid invokes a perfect day when “the air shifted with the shimmer of actual angels” and “sunlight / stayed like a halo on hair and heather and hills.” When the poet meets “the woman from the fish-shop,” he marvels at the weather, only to be told by her in the poem’s last line: “We’ll pay for it, we’ll pay for it, we’ll pay for it!”

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2021

IT IS CUSTOMARY TO START an essay about Kafka by emphasizing how impossible it is to write about Kafka, then apologizing for making a doomed attempt. This gimmick has a distinguished lineage. “How, after all, does one dare, how can one presume?” Cynthia Ozick asks in the New Republic before she presumes for several ravishing pages. In the Paris Review, Joshua Cohen insists that “being asked to write about Kafka is like being asked to describe the Great Wall of China by someone who’s standing just next to it. The only honest thing to do is point.” But far from

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2021

A MAN AND HIS FAMILY are vacationing in a tiny village in France. On the eve of their planned departure, the man’s wife and son disappear. He embarks on a hopeful search, asking for information about his missing family from neighbors and the local police. They went to pick up eggs and they didn’t come back, he tells anyone who will listen. But it’s September, and, with the other Parisian vacationers gone, the town—usually sunny and cheery—has transformed. It’s cold and wet, and the townspeople, once spirited and deferential to visitors, are distant and unhelpful. They are also confused by

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2021

LAURENCE STERNE DESIGNATED the poet and novelist Tobias Smollett a “Smelfungus” in his 1768 novel-length travelogue A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy. Smollett published his travelogue Travels Through France and Italy two years before, and Sterne’s punishing evaluation of that work is as follows: “The learned Smelfungus travelled from Boulogne to Paris,—from Paris to Rome,—and so on;—but he set out with the spleen and jaundice, and every object he pass’d by was discoloured or distorted.—He wrote an account of them, but ’twas nothing but the account of his miserable feelings.” That judgment could equally apply to P. Lewis (aka

- review • November 19, 2020

ELENA FERRANTE DOES NOT require privacy. She lays out her psychosexual-emotional range for all the world in multiple languages. She does not lock down her time, although she controls its use: one written interview in each language with each book. What she avoids is the parade, the opportunity for outsiders to evaluate aspects of her she is not ferociously driven to present. That is why she wrote a letter to her publishers in 1991, before they released her first novel, Troubling Love, before she knew whether she would find one reader or one million. In the letter, she gently refused

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2021

“SENESCENCE” ISN’T QUITE THE RIGHT WORD for the stage the writers of the Baby Boom have reached. Sure, they may be collecting social security, the eldest of them in their mid-seventies, but the wonders of modern science may allow some another couple of decades of productivity. When the Reaper starts to come for the writer’s instrument, the first thing to go is flow, but that may not matter: fragments are in. In a decade or so, robbed of their transitions and reduced to accumulating prose shards, the octogenarian Boomers may find themselves newly trendy. A strange fate for a generation

- review • October 6, 2020

Authors have long asked whether fiction is useful in times of crisis, a question that has been especially pronounced in the past four years, following the election of the current president, the advent of coronavirus, and the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. What can a book do in a time like this? It’s a question central to Want, Lynn Steger Strong’s second novel. The narrator, unnamed until the penultimate page, asks herself throughout the book: Why did I study English? Why did I think that sharing books with people was a worthwhile way to spend my life?

- review • October 1, 2020

Most fiction about North Korea published outside of that country is by defectors and dissenters, and most of it tells of the hardships of living under a totalitarian regime. Fiction published in North Korea tends to be the opposite: when I visited in 2017, the only English-language books at the bookshop that passed as fiction were hagiographic historical novels about former supreme leaders.