LYDIA DAVIS INTRODUCED her brand of emotional vertigo in the mid-1980s, with short stories that could fairly be called flat but never cold. In her fiction and translation work—both lifelong gigs for her—Davis revises drafts heavily. Her patience has given us a catalogue of everyday American surrealism that is hers alone. Here is a story from 1986, in its entirety, called “Safe Love.”

She was in love with her son’s pediatrician. Alone out in the country—could anyone blame her.

There was an element of grand passion in this love. It was also a safe thing. The man was on the other side of a barrier. Between him and her: the child on the examining table, the office itself, the staff, his wife, her husband, his stethoscope, his beard, her breasts, his glasses, her glasses, etc.

Davis throws us from side to side here, in a text so narrow the walls almost touch. There is “grand passion,” but the stakes are low enough—for us or the characters, it isn’t clear—that we end on a dismissive “etc.” Things that may be barriers include the pediatrician’s office and the mother’s husband—also breasts, though they seem more likely to be an accelerant. Do we find ourselves caring about an outcome after so little time? I do. The title gives us an early conclusion: this love is safe but from what?

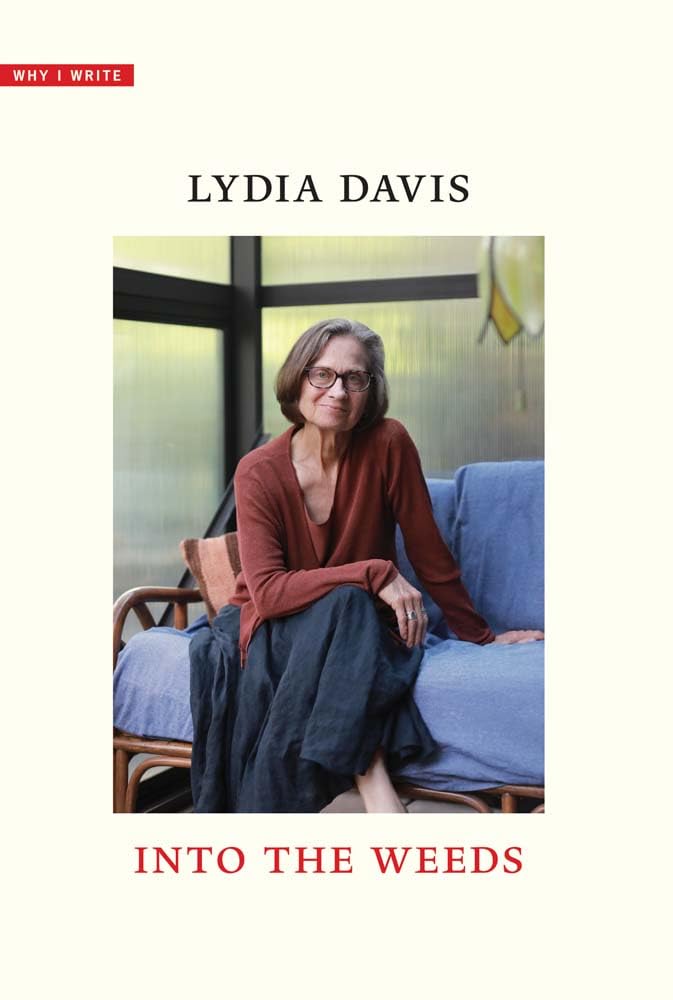

Davis’s new book Into the Weeds is an entry in Yale’s “Why I Write”series, which turns the university’s Windham-Campbell Lectures into slim volumes. Davis delivered her remarks on September 18, 2024, and revised them for this format. This book describes a part of her process—how ideas “bother” her until she starts writing about them. She focuses mostly on work from the past twenty years, writing that is substantially different from the stories that established her reputation.

To get closer to her initial impulses, we can go back to the older essay “Found Material, Syntax, Brevity, and the Beauty of Awkward Prose: Forms and Influences IV,” derived from her 2012–13 NYU Master Class. Davis writes here about a book by “French surrealist and ethnographer Michel Leiris” called Nights as Day, Days as Night. She does not mention having translated the first three volumes of Leiris’s memoir The Rules of the Game (which is a bit like Paul McCartney describing John Lennon’s Imagine but declining to mention they were both in The Beatles).Those three Leiris books—Scratches, Scraps, and Fibrils—are dense with the syrup of consciousness, high piles of coiled sentences that left me completely open to myself when I finished them. Days as Night is “a collection of the more interesting dreams Leiris had recorded over forty years,” Davis writes, which Leiris mixes in “with accounts of waking experiences that resembled dreams.” Leiris’s prose in these entries is much simpler than that of the memoir—much closer to the sound of Davis, in fact. Here is one dream that echoes the concentrated motion of “Safe Love”:

NOVEMBER 20–21, 1923

Racing across fields, in pursuit of my thoughts. The sun low on the horizon, and my feet in the furrows of the plowed earth. The bicycle so graceful, so light I hop on it for greater speed.

Davis says that Leiris demonstrates “how fine the line was between the irrationality of the dramas that take place while one is asleep and the weirdness of events in everyday waking life.” She then follows with a description of Leiris that feels like a description of Davis’s own short stories. “The account of the waking experience,” she writes, “can be written in such a way as to include only the strange elements and leave out the elements that might have ‘normalized’ it in the telling.”

This is that Davis feeling, a familiar unfamiliarity, that you find in stories like “Break It Down,” in which the narrator tries to reconstruct in forensic detail whether or not her ex-boyfriend is lying to her, with descriptions of cigarettes and garage doors becoming so obsessively parsed that the whole scene levitates as the uncanny and boring battle for control. In “The Fears of Mrs. Orlando,” a racist woman says she sees someone under a car grab “her stockinged ankle with his black hand,” though no man ever appears, nor does anyone grab the purse she drops. Davis pursues the line between real and imagined with a review of concrete evidence (glasses, phone calls, breasts) that makes her stories feel a bit like reports from the dream police, only there is no punitive mandate. She seems like someone who would reward the average conscious person for noticing that they are closer to dreams than they thought.

Those stories are far from the mood of Into the Weeds, which is autumnal in more than one sense. Davis talks about “her village,” a town in upstate New York where she has lived for twenty years and which embodies the idea of the sleepy (and possibly exclusive): “Along the road, vehicles pass now and then, not very often, although as each new house is constructed up the road, in the woods east of where I live, there will be another one or two cars going by.” Her activities have narrowed: “My translating life is more or less over now.” She presents herself as reluctant to be doing the lecture at all, describing it more than once as something she was “asked” to do, a kind of modesty that is not unusual for her. What she does not mention is the deaths, in the space of only a few years, of her child, grandchild, and ex-husband. It is hardly any writer’s obligation to divulge personal information, and Into the Weeds is not a confessional book or a diary. The shadow, though, of these ruptures is palpable.

Davis begins her 2024 lecture by telling us that she was “beginning to struggle to answer the question of why I write” when she found a John Ashbery interview. In discussing the titles of his poems, he says, “They come to me.” To explain why he titled a poem Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, Ashbery mentions seeing a reproduction of young Francesco Parmigianino’s work of the same name in a magazine. Ashbery writes that he was “immediately grabbed and bothered” by the painting, and this is where Davis picks up her cue. “After I have been asked why I write, and as I am attempting to answer that question,” she writes, “the word bother becomes relevant in a particular sense, though I was not conscious of it in just that sense one year ago, before I read what I read recently.”

Davis grabs the verb that animates Into the Weeds: “The reason I write a particular story may be because something—which I call ‘material,’ as in ‘raw material’—bothers me until I ‘do something’ about it.” This bother registers with Davis “pleasurably, though a little anxiously.” From there, she wants to “find a form for it that fits it perfectly—or rather, the material itself evolves into the form that suits it; you worry it, going through it again and again until nothing about it seems wrong; now you have done something about the thing that bothered you, and in doing that, you have gotten rid of it.” The “again and again” feels central to her work, and she has written extensively in essays about how much she revises, as any great translator must: weighing the possibilities that can never be as right as the original, as written language can never entirely represent a dream. Davis says this bothering element is “something I don’t fully understand and that I want to understand.” The writing really does sound here like translation: “Perhaps I think that putting a thought into a formal piece of writing may help me understand a puzzle.”

Some of the events that bother Davis into writing are the “beauty of the black cows across the road, the geometry of the positions they adopted,” and “the shadow of a grain of salt on a counter.” About the salt, she says, “I am bemused and a little in awe when I see how long a shadow is, cast by the near-horizontal afternoon sunlight, from a single grain of salt on the kitchen counter.” If this found its way into a story, I do not know about it.

About the cows, she has much more to say. She tells us she accumulated the story over three years, writing without any intention. She looked out the window at the cows, “who, over the years, started by being three heifers, then grew up, two of them bearing one calf each.” (Her care with cadence is there in that excerpt, clauses deftly distributed across beats and ideas.) Davis took these “eighty-some observations” and made a chapbook, which includes some fairly indifferent photos of the cows. One emotion she describes having during the writing of the story is “the demanding pleasure of setting down my observations of them,” which I do not entirely understand. Was it demanding writing down all these static scenes? (I realize now that I sound like Davis while I think about Davis revising Davis.) Another emotion is her “pain and sorrow over the treatment of most cows in the world,” which shocked me. This chapbook is an almost eventless diary of how the cows looked, most similar to her 2012 story “Cape Cod Diary,” which describes her time writing on Cape Cod and observing the movements of various boats. The only passage in “The Cows” that reflects these emotions is this: “It is hard to believe a life could be so simple, but it is just this simple. It is the life of a ruminant, a protected domestic ruminant. If she were to give birth to a calf, though, her life would be more complicated.” The first two sentences both hitch and repeat one word each—“simple,” then “ruminant”—as if Davis is struggling to say something, which is perhaps how much she loves these cows. “Though my objective portrayals may not appear overtly loving, there is love in the motivation behind them,” she writes in Into the Weeds.

Davis tells us “another emotion shows through” in “The Cows.” This is “a strong feeling on my part, not suppressed, determining the choice of what I describe.” There is a bit of anticipation here—what is stronger than love, or at least more important to come last in this small series of two? Davis calls this feeling “more abstract, almost clinical, despite my loving motivation.” What drives here is the search for “an exact match between what I saw, what pleased and interested me at that moment, and the words that would describe it so exactly that there could be no other way to describe it.” So what eliminates the bothering, the “demanding pleasure” that took her three years of notation, is this ecstatic exactness, the moment when words have finally broken through and given us their strangeness, made it clear that they must represent descriptions of things as they actually exist.

DAVIS ALSO TAKES UP her own reading and how that factors into her work as a writer. Though she touches briefly on James Baldwin and Vladimir Nabokov, Davis spends most of her time on a book about wheelwrights written by George Sturt (obscure, at least to me), and two books by Knut Hamsun (well-known).

Davis describing her own reading experience reveals her care for word choice and respect for revision (which seems central to the work, also, of the translator). She says, “we change our ideas, too, especially if we are reading one book after another and thinking and talking about what we are reading.” “If I read Baldwin steadily, a little each day,” Davis wonders, “while I write this essay, as I alternately read his novel and return to writing this, will I pick up some of his fluidity, his skill in creating seamless transitions?” She goes on to hope that she might be influenced by “his fine distinctions and subtle nuances.” Her closer is a perfect reading writer’s reading anxiety that doubles as a goal: “Will I read Baldwin, then read a paragraph of my own and revise it upward?” “Revising upward” is what it is, the work of being someone who jumps into the stream, floats in the stream, and then hops out to describe the stream.

The three parts of the Davis practice are short story writing (with one novel popping up, early on), translation, and the writing of essays very much like Into the Weeds. 2019’s “Revising One Sentence” is an earlier unpacking of her writing process that maps one particular revision and some tendencies she’s noticed over time. “Some sentences want to be stories right away,” Davis wrote. “The latest one that grew immediately into a story—still in rough form at the moment—was ‘It took the Queen of England to make my mother stop criticizing my sister.’ This happens to be true.”

The book she spends the most time on is George Sturt’s The Wheelwright’s Shop (1923), which she confesses she had to force herself to read at times. Along this road, she finds interesting things that I also find interesting; for instance, “that a blacksmith did not wish to admit sunlight into his shop because the bright light made it difficult for him to perceive and measure the precise intensity of his fire.” I am grateful, as I would not read even a short book about wheelwrights. The wheelwright details inch toward the “weirdness of events” that seems to me like Davis’s true love, her North Star.

Reading The Wheelwright’s Shop took me some months, and after I was done, it remained in my mind to “bother” me—in the good sense of posing a question. Although the friend who gave me the book had read it, and thought I would like it, and although I had read it, and liked it, in the end, it did sometimes border on the tedious and I had to wonder how many other people would be likely to read it.

Davis tells us she persisted reading about wheelwrights because of Sturt’s “character as it comes through—in other words, the voice you listen to, the company you keep.” In her stories, Davis has no unitary voice. In essays like Into the Weeds, she is predictably patient with herself and us and is absolutely good company. The second reason she reads Sturt is “the style of the writing itself.” How does Sturt get results? “He deals out short, emphatic sentences,” Davis explains, and offers as examples: “If they didn’t, you knew it,” “He felt that it looked right,” and “A tricky job, this.” These are close to the narrating voice of many Davis stories, like this from “Mr. Knockly”: “It was early October. The days were long and cool. I went out every evening and walked.” When Davis reaches what she likes most about Sturt, she indirectly reveals one of her secrets (if we accept the cross-referencing with other essays earlier indicated).

Sturt’s writing is, she says, “above all exact.” In the particular case of his book, Davis reckons it must be due to the nature of the subject. “It must be all about exactness,” she writes, “because the correct construction of a wagon is all about exactness; approximation has no place in it.” (She also likes that he does it “mostly without metaphor,” a rule she often follows.) Davis isolates Sturt’s “care for detail, specificity, and precision in his descriptions” and calls it “his way of seeing things.” (Sturt at one point describes the distance between two points as “three or four minutes of level street,” which is vivid.) But Davis does not want to write about technical processes and had trouble even finishing Sturt’s book. In her own writing, Davis needs exactness and certain details arrayed just so to deliver the weird daylight dreams that her beloved Proust and Leiris could find in cookies and carpets and graffiti. As for what bothers her now, it feels like more than cows but the cows are what she sees.

Sasha Frere-Jones is the author of the memoir Earlier (Semiotext(e), 2023).