THE SPIRITUAL AND AESTHETIC DIMENSIONS of Andrey Tarkovsky’s cinematic universe might easily produce a daunting tome with the heft of a life-size, ready-to-bear cross. Yet Andrey Tarkovsky: Life and Work succeeds in compressing the late Russian director’s monumental legacy into portable form—a slender volume a pilgrim could easily slip into a backpack. The book succeeds in distilling Tarkovsky’s sound-and-visionary, contrarian essence with an approach that is at once capacious and compact: It’s more imagistic gospel than catalogue, more consecrated poetry than academic contextualization.

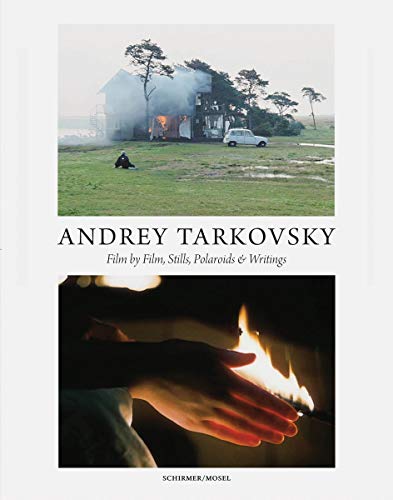

Subtitled Film by Film, Stills, Polaroids & Writings, this volume of atmospheric elements has been arranged by Andrey Tarkovsky Jr., Hans-Joachim Schlegel, and Lothar Schirmer into an uncluttered tableau vivant. A bountiful introductory essay by Schlegel presents the “anti-avant-garde avant-gardist” Tarkovsky on his own mystically charged terms. His seven feature films are each represented by a short synopsis—the 163-minute Stalker recapped in about two hundred words—and roughly thirty pages apiece of uncaptioned, staggeringly evocative images: a spectral continuum of the autobiographical, the metaphysical, and the sensual. Flaming objects, medieval icons, figures and faces that could be those paintings’ earthly descendants, pantheistic apparitions, catastrophic landscapes, here an overturned horse, there a woman floating above a bed. Separate sections of Russian and Italian Polaroids, as well as a “Family Album,” are no mere curios, but have the fated air of artifacts recovered from a shipwreck.

Alongside a brief but useful selection of his writings, the “Other Writers on Tarkovsky” are an odd lot. Sartre’s tendentious 1962 defense of Ivan’s Childhood against charges of anti-Sovietism abuts testimonials from esteemed colleagues and a rapt five-sentence blurb from Ingmar Bergman. Then comes Aleksandr Sokurov’s “The Banal Egalitarianism of Death,” a thing apart. An elegy upon “the death of a GREAT man” (also in anguished all-caps: “GENIUS,” “SOUL,” “SUCCOUR,” “GOD”), it is an unhinged burst of mourning, exultation, disputation, reverence, and despair. Sokurov was thirty-five when Tarkovsky died, in 1986, just establishing himself as a filmmaker but aware he might never escape his idol’s shadow. He worships—and partly resents—Tarkovsky as an embodiment of the tortured Russian soul, a holy man in the clothes of a dandy, a beatific heretic who understood the Book of Revelation as a love song.

For Sokurov and Tarkovsky, the right image is worth a thousand dissertations; the waking lucid dream of cinema can never truly be “unpacked,” only experienced, surrendered to, and wrestled with.