It’s six o’clock in Tehran and Kate Millett needs a drink. It’s not easy, being a maquisard of the feministas. It is March 1979, only weeks after the departure of the Shah of Shahs. Iran is in the throes of revolution. Streets are being renamed, monuments defaced, pissed upon, torn down; there is graffiti everywhere. Call it the chrysalis phase after five decades of Pahlavi absolutism: No one knows what’s being born, but everyone wants it to be beautiful. (Beauty, alas, is in the eye of the beholder.) Millett, forty-four years old, tousle-haired and bespectacled in the frog glasses of her era, is in the Iranian capital with her partner, the Canadian journalist Sophie Keir, heaps of 16-mm film and audio recording equipment in tow. Upon arriving several days before, the pair had found “young men with machine guns lolling about” and packs of women wearing the chador, or floor-length veil. They were “like black birds, like death . . . terrifying, hostile, ancient, alien,” Millett will write in Going to Iran, a lively book-length account of her visit. To her alarm, no one has been sent to the airport to welcome them. They find shelter in a bland American hotel. When a foreigner in a foreign land . . .

The occasion for Millett’s Eastern excursion is an invitation to speak on International Women’s Day. This was a first, a sign of the times. During the shah’s reign, the regime had held its own celebration, commemorating the day in 1936 that his father, the modernizing monarch Reza Shah, had—shades of Atatürk—banned the wearing of the veil in what remained a largely traditional country. Women who resisted the decree had their veils forcibly removed; their husbands were fined, their homes searched. The veiled were banned from cinemas and public baths, too. During Millett’s stay, some of her Iranian hosts will acknowledge advances for women under the Pahlavis, but Millett won’t have any of it. Though she considers the veil an apparatus of oppression, she writes off the ban and other oft-cited improvements as “tokens”: a form of “state-co-opted feminism,” the “window dressing of modernization.”

She is an American and a lesbian. Thankfully, no one seems to notice the latter, although the former leaves her open to allegations of being a spy. Her credentials are not trifling. Her visage graced the cover of Time in 1970, after the publication of her first and most famous book, Sexual Politics; that same year, the New York Times dubbed her “the Karl Marx of the women’s liberation movement.” Andrea Dworkin, her fellow ur-feminist, would later observe, “The world was sleeping and Kate Millett woke it up.” Millett’s interest in Iran is more than a passing dalliance; for several years she has been a member of the Committee for Artistic and Intellectual Freedom in Iran, or CAIFI, an organization of students and intellectuals agitating against the shah on university campuses and in the liberal press. While the US administration may have equivocated over their man in Iran, CAIFI railed unremittingly against the shah’s electoral follies, his prisons, his excesses.

About Iran, Millett has a great deal to say. With regard to Ayatollah Khomeini, the so-called Gandhi in robes and the figurehead of the Iranian revolution, she says he “talked differently in Paris.” By Paris she means the roughly three months the cleric pontificated from his humble dais in the Parisian suburb of Neauphle-le-Château, mumbling sweet, gnomic nothings about the democratic utopia to come. As to Khomeini’s deceptions, she is not incorrect. Some forty days before her arrival, he landed in Iran, after years in exile, on a chartered Air France flight stuffed with members of the international press; already he has revoked a law that afforded women access to civil divorce and abortion. He has denounced coed schools as “centers of prostitution.” One of his closest associates has declared women “too emotional” to serve as judges. The day after Millett arrives, Khomeini proclaims that women working in state ministries must wear the veil or risk losing their jobs. Ya roosari ya toosari, “Cover your head, or be smacked in the head,” goes the creepy chant of men—and a not insignificant number of women—in Tehran that day. For Millett, the veil represents the patriarchy. For Khomeini, the chador is the very “flag of the revolution.”

The American gets to work. A modern-day Xenophon armed with a portable tape recorder, she is consumed by the task of memorializing the struggle of Iran’s beleaguered feminists. “We didn’t make a revolution to go backwards,” Iranian women shout during the several days of protest against Khomeini’s decree. Millett is enthralled, if a little lost, fumbling through the chants, peppering her youthful translators with questions. “I had never heard feminists speak this way before,” she tells a group of French feminists. (Liberation Movement of Iranian Women: Year Zero, the short film they produce, is one of the best documents of this moment.) When she misses what might have been a pivotal photo op—protesting women hoisting themselves over locked university gates—Millett beats herself up. “They had begun the revolution,” she laments, sighing into her recording device. Millett is an ardent, if comically earnest, believer in the power of the media, a self-styled archivist and panegyrist of the female cause. For a minute, she considers calling the documentary she is working on The Battle of Tehran, after Gillo Pontecorvo’s classic film about the Algerian War.

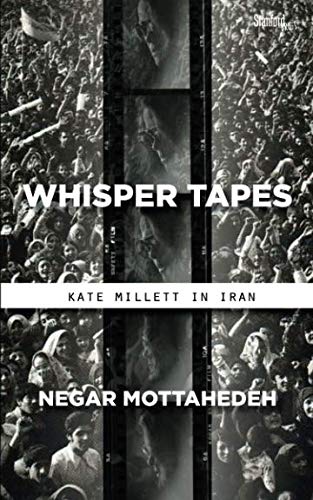

The scholar Negar Mottahedeh’s inspired premise is to excavate the intimate traces of Millett’s trip on the “whisper tapes” she left behind, which have since been deposited at Duke University, where Mottahedeh is a professor of literature. A Farsi speaker, she meditates on these scratchy audio files, filled with Millett’s breathless, occasionally self-mythologizing narration, as well as the incidental sounds of a season of revolution entering its last act. She lingers over the gaps, the double entendres, the untranslated and the untranslatable. Call it a form of forensic listening. Farsi is notoriously nuanced, Iranian culture rife with dissimulation, doubled meaning, false flattery. Inevitably, Millett misses a lot.

“Muslim fanatics!” she is prone to saying about the unfamiliar people around her. In fine misandrist form, she inveighs against a man on the sidelines of one protest, not realizing that he is in fact there in solidarity. She is told, time and again, that the veil is not the most salient problem. “We are fighting for equal rights with men,” one woman explains. “We do want to wear the chador,” another insists. When an American Sufi and longtime resident of Iran suggests that the protests are not antireligious, Millett is not listening, but fumbling with her camera instead. “I don’t think Mrs. Millett can solve Iranian problems,” says one young university employee captured on the tapes. “She has so much problems of her own to solve!”

To be clear, Millett has stepped into a women’s movement at a perilous crossroads. As Nasser Mohajer and Mahnaz Matin have shown in their sensitive research on this period, not one of the secular groups that participated in the revolution made a peep about Khomeini’s March decrees. The situation, as they say, was fluid. As ever, the Marxists recited their standard handbook mantra: Revolution first, gender rights later. More crucially, there remained a hope among both nationalists and leftists that they might prevail in the new regime; alienating the ayatollah and his supporters would be risky. The secular revolutionaries felt a revulsion, too, at the thought of making common cause with the royalists and the emperor-in-exile. When state television, newly under the sway of the Islamists, briefly acknowledged the women’s protests, it zoomed in on fur coats and oversize glasses, ciphers for the decadence of the old regime. Witness these prostitutes of the petite bourgeoisie!

Mottahedeh’s book follows an imaginative structure that allows for lovely diversions: There is a section for each letter of the Persian alphabet, thirty-two in all. F is for Oriana Fallaci, the Italian journalist who addressed the ayatollah as “dictator” during her unforgettable 1979 interview with him. The French feminist movement, exemplified by a turban-wearing Simone de Beauvoir, makes several cameos. Toward Millett, Mottahedeh is judicious, diplomatic even, as the distinguished visitor negotiates her way around the wreckage of a revolution Michel Foucault once called “the most modern and the most insane.”

We know how the story ends. The leftists, many of whom are Millett’s friends, are frozen out of the Islamic Republic. (Most of them, imprisoned or exiled under the shah, will learn to fear and despise Khomeini, too.) “Kate, your sisters need you in Iran,” says a friend on the eve of her departure. Among many other things, this is a book about the thrill of solidarity. It is also about its limits. “Can you imagine going through a whole revolution and not being able to have a glass of wine after it’s all over?” Millett asks, at the end of one of her most frustrating days in the Iranian capital. As it happens, many people can.

In her obsession with Islam and the veil, Millett calls to mind many a well-intentioned missionary in the East, fixating on the most conspicuous visual markers of the women’s issue as an index for a country’s freedom. (Think of the bounty of articles on women and driving in Saudi Arabia, as if the right to be behind the wheel of an SUV represented the crux of female empowerment.) At times Millett misses the subtlety in an uprising, a new country, and a new feminism that is, to paraphrase a popular slogan of the time, neither Eastern nor Western. For the American Sufi, one of the book’s more beguiling supporting characters, what’s happening is “not a draconian return to Islam but the most modern form of revolt against a global system of injustice.” For Mottahedeh, these women suggest “a vision of a nation that is both free and bound to the life of the spirit.” Perhaps this nuance is why this revolution, and this country, has confounded the world for four decades and counting.

Millett is deported on March 19, exactly fourteen days after her arrival. She will not be around to witness Khomeini’s total ascent and the apotheosis of clerical rule, a raft of political assassinations, or eight years of war with neighboring Iraq. Like a hostage released from torturous captivity, she burbles with relief upon her arrival at Charles de Gaulle. “I love Paris. I’m so glad to be in Paris,” she cries. You can see it for yourself on YouTube. Her first stop: the Brasserie Lipp, where she will finally have that elusive drink.

Negar Azimi is senior editor of Bidoun.