What was Susan Sontag’s preferred pronoun: “I” or “one”? First- or third-person singular? Which of those substitute-words revealed—or concealed—more about the woman who reigned as the leading cultural authority during the second half of the twentieth century but who refused to explicitly acknowledge her same-sex relationships? From the second paragraph of “Notes on ‘Camp’” (1964): “I am strongly drawn to Camp, and almost as strongly offended by it. That is why I want to talk about it, and why I can.” (The declaration all but trumpets her membership in the lavender mafia.) Toward the end of that career-launching essay, in the fifty-third of the piece’s fifty-eight pensées: “Yet one feels that if homosexuals hadn’t more or less invented Camp, someone else would.” (This strange repudiation seems to evince her anxiety about her own homosexuality, or, at the very least, about her intimate understanding of homosexual arcana.) From “Afterword: Thirty Years Later,” written on the occasion of a 1996 reissue of Against Interpretation and Other Essays, the volume that included “Notes on ‘Camp’”: “I was a pugnacious aesthete and a barely closeted moralist.” (The line appeared when Sontag was several years into her closeted relationship with Annie Leibovitz, which would be the longest of the writer’s life and last until her death; although an open secret for most of its duration, the romance went unmentioned in Sontag’s obituary in the New York Times.) From a 1978 essay on Walter Benjamin, who ranked as one of her many lodestars, that provides the title for her collection Under the Sign of Saturn: “One cannot use the life to interpret the work. But one can use the work to interpret the life.” (Are these words meant as a warning to those wishing to write about her and the aspects of her life that she wished to keep hidden?)

In Sontag: Her Life and Work, Benjamin Moser contravenes the first part of her ’78 dictum (as the subtitle of this perceptive authorized biography suggests), using the circumstances of her life to consider the oeuvre of “America’s last great literary star.” Appearing almost fifteen years after Sontag’s death, from blood cancer at age seventy-one, in December 2004, Moser’s book keenly traces her Story of the “I,” matching that imperial yet often unstable pronoun with its proper antecedent—a project that entails reconciling “I” with “one,” “Susan” with “Sontag.” Sontag builds on the first two volumes of her journals and notebooks, the publication of which was momentous for the new light they shed on the writer and, to some extent, on her writing: Reborn (2008), covering Sontag’s life from 1947 to 1963, and As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh (2012), spanning 1964 to 1980. (A third, final installment of the journals had originally been planned; I do not know its current status.)

Chief among the many astonishments of the Sontag diaries—which Moser excerpts and expounds upon at length, including entries that have never been published—is the extent to which they reveal the commanding, valiant public figure at her most defenseless, often emotionally devastated by her female lovers (with whom she typically exhibited florid self-abnegation) and consumed by how good or bad she was in bed. That dichotomy is particularly pronounced in As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Although the book encompasses the period of Sontag’s most prodigious output and her greatest intellectual influence—the era of not only Against Interpretation but also On Photography (1977) and Illness as Metaphor (1978)—the volume is primarily an “elaboration of romantic loss,” as David Rieff, her son and the editor of her diaries, notes in the preface. The first entry in As Consciousness, from May 1964—the same year she wrote the salvo “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art,” at the end of the essay “Against Interpretation”—finds Sontag grieving over her relationship with the playwright María Irene Fornés (“Her very ‘life’ depends on rejecting me, on holding the line against me”), which had ended in 1963. Several passages from 1970 recount her masochistic attachment to Carlotta del Pezzo, a druggie Neapolitan aristocrat who, per Moser, “was notably indolent even by the standards of her milieu.”

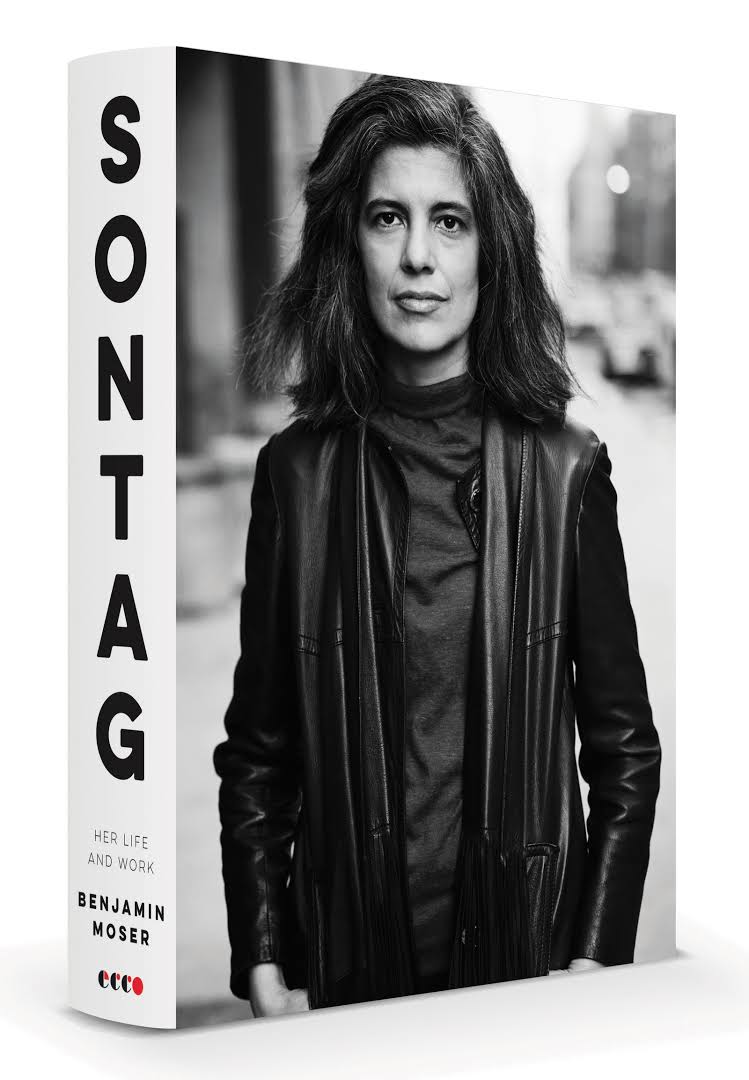

The journals, then, provide fascinating glimpses into what was happening off-camera, into the turmoil masked by the mien of indomitability that defines the photographs taken of Sontag in the ’70s: Peter Hujar’s portrait from 1975, in which, even in a supine, vulnerable position, she appears unconquerable, or the 1978 Richard Avedon photo (shot for Vogue) of a leather-jacketed Sontag, in full soft-butch splendor, that has been used for the cover of Moser’s book.

With Sontag, Moser intelligently brings together both public and private, onstage and off-. His scrutiny of her essays, fiction, films, and political activism is clear-eyed, his analysis of her tumultuous affective life sympathetic (if at times slightly less astute). Sontag offers a thoroughly researched chronicle of an unparalleled American figure and the institutions tied to her: the Partisan Review; Farrar, Straus and Giroux. It is deft and sometimes dishy (especially succulent: the details of a brief affair with Warren Beatty). If Moser’s Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector (2009) was indispensable in greatly expanding the Brazilian writer’s profile and readership, especially in the US, then Sontag accomplishes something just as valuable: It deepens our understanding of a world-renowned eminence, one who, since her death, has been the subject of an HBO documentary, an off-Broadway production, and several books (most of them insignificant, though two memoirs, Rieff’s Swimming in a Sea of Death, from 2008, and Sigrid Nunez’s Sempre Susan, from 2011, stand out for their intimate, insightful observations). The timing of Sontag’s publication is felicitous, too. Moser’s book arrives a week after the September 8 closing of the Met’s “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” an exhibition that prompted innumerable witless pieces, in the New York Times and elsewhere, attempting to parse the significance of Sontag’s still-dazzling essay. Sontag rescues Sontag from further inanity, reminding us of the majesty of so much of her writing—even (especially?) that composed by someone who endured (and later inflicted) extreme debasement.

“It’s only since I’ve started reading her from A to Z that I realize how much she wrote and did,” Moser told the Times in February 2013, in a brief notice announcing his appointment as Sontag’s biographer (Rieff and Andrew Wylie, Sontag’s agent, had approached him about the project). “It’s hard to think of a writer’s life that ranged as widely.” Or to think of a writer with such a roving “I.” Moser calls attention to a journal entry from Reborn composed on New Year’s Eve, 1957, when Sontag, then twenty-four, was living in Paris and in a miserable relationship with Harriet Sohmers, and more than five years away from the publication of The Benefactor (1963), her first book (and first novel): “My ‘I’ is puny, cautious, too sane. Good writers are roaring egotists, even to the point of fatuity.” By 1978, she was boldly using the pronoun for a collection of short stories, I, etcetera, which includes at least one work of memoir masquerading as fiction: “Project for a Trip to China,” a tale haunted by Sontag’s father, who worked as a fur trader in the country and died there, of tuberculosis, in 1938, when Susan was five.

Yet, as Moser points out, “Sontag’s most personal works are precisely those in which she most determinedly elides the ‘I,’” such as Illness as Metaphor, published the same year as I, etcetera. In this landmark critical study about the distorted language used to describe TB and cancer, among other diseases, Sontag never once mentions the impetus for the book: her own experience with breast cancer, diagnosed in 1975 and resulting in a radical mastectomy followed by four additional operations and “thirty long months of chemotherapeutic bombardment.” Although “I”-less, Illness as Metaphor is motored by Sontag’s own fear and her fury at the myths then still attached to cancer—for instance, that the disease was somehow linked to repression—harmful misconceptions that this potent monograph was instrumental in dismantling.

Sontag’s “I” functioned, as she grew more prominent, as an Ionic column, an imposing structure that could be split in two, sometimes cleanly and evenly, sometimes not. Moser cites passages from “Singleness,” her short essay from 1995, to illustrate this schism: “Every writer—after a certain point, when one’s labors have resulted in a body of work—experiences himself or herself as both Dr. Frankenstein and the monster”; “In my ‘Sontag and I’ game, the disavowals were real. Oppressed by as well as reluctantly proud of this lengthening mini-shelf of work signed by Susan Sontag, pained to distinguish myself . . . from her . . . I flinched at everything written about her, the praise as much as the pans.”

Two telling phrases jump out from this excerpt, each suggesting varying levels of Sontag’s self-awareness. The first: the disavowals were real. Sontag was notorious for her renunciations, already glimpsed in the lines from “Notes on ‘Camp’” cited above. One of her more infamous volte-faces concerned communism, which she saluted in “Trip to Hanoi” (1968) but denounced at an event at Manhattan’s Town Hall in 1982, calling it “Fascism with a human face.” Another turnabout concerned images. In On Photography, her highly ambivalent treatise on the medium, she wrote that “photographing is essentially an act of non-intervention.” Yet Sontag would revise and refine that position several times over the decades, a process that began with her many heroic ventures in Sarajevo during the Bosnian War in the ’90s. Leibovitz accompanied her to the region on occasion, documenting the bloodshed for Vanity Fair: The photographs, even if incongruously placed near articles on Hollywood A-listers, nonetheless made millions aware of the horrors in southeastern Europe and were thus “essential . . . to the Bosnian cause.”

Moser assiduously traces and analyzes—and often commends—the reversals made by Sontag the public figure: the writer, the activist, the intellectual who once said “the very nature of thinking is but.” On her political shifts, he’s especially sharp: “Her [1960s] radicalism became passé, but her liberal activism formed one of her enduring legacies: an argument for culture as a bulwark against barbarism, for the connection between art and the political values that guaranteed individual dignity. . . . Sontag argued for the centrality of culture with a conviction that rallied people all around the world, and became genuinely countercultural in a way she never was in the sixties.” That conviction was evidenced not only during her time in Sarajevo, where she mounted a production of Waiting for Godot in 1993. In 1989, during her tenure as president of PEN America, Sontag demonstrated unwavering support for Salman Rushdie by organizing a reading of The Satanic Verses shortly after the fatwa had been declared against him and after several writers had abandoned him. Even in the last weeks of her life she remained committed to her role as cultural emissary: While at Sloan Kettering, the Manhattan hospital where she would die, Sontag reworked and completed her introduction to Under the Glacier, by the Icelandic novelist Halldór Laxness.

But Moser’s elucidation of Sontag’s other arresting phrase from “Singleness”—Dr. Frankenstein and the monster—proves even more engrossing. (She seemed to have been drawn to evil creations and dual natures; one of the stories in I, etcetera is called “Doctor Jekyll.”) Part of that illumination involves recounting Sontag’s monstrous behavior: the snubbings (often of younger writers whom she had initially embraced, only to drop them for not having shown sufficient obeisance or for some other mysterious infraction), the rococo displays of indignation (especially toward those who didn’t share her somewhat deluded belief later in her life that she was foremost a fiction writer, not an essayist). Joan Acocella, who wrote a glowing profile of Sontag, “The Hunger Artist,” for the New Yorker in 2000, admits that spending time with her was “like being in a cave with a dragon.” Exceptionally appalling was Sontag’s conduct toward Leibovitz, whom she met in 1988. (How they got together: Through a mutual friend, Sontag had asked Leibovitz to take new author photos of her; Leibovitz seduced the writer by telling her how much she loved The Benefactor, a novel admired by few.) “Their love affair . . . would be expressed in a language that many watching from the outside found hard to decipher,” Moser notes. According to Sontag’s friends, she would call Leibovitz “dumb” and “stupid,” upbraiding her in public for not knowing enough about, say, Artaud or Balzac. “It was like a child and an abusive mother,” a former assistant of Sontag’s tells Moser. Leibovitz, clearly occupying the role of emotional submissive that Sontag had often assumed in many of her previous relationships with women, tells him, “I would have done anything.”

The section devoted to this fractious relationship occasions one of the few times in Sontag that I was baffled by a descriptor chosen by Moser, who has a gift for the mot juste. “Susan could lend Annie a high-culture respectability, but Annie could make Susan cool,” he writes. Cool isn’t the word that springs to mind when looking at the 2000 Absolut ad shot by Leibovitz featuring a highly airbrushed Sontag, posed in high literary-lioness mode. Camp comes closer.

Despite that minor misstep, Moser’s analysis of the Sontag-Leibovitz coupledom stands as one of the more incisive parts of an already shrewd biography for the attention he pays to the toll exacted by the closet: on not just Sontag’s life (including her emphatic denial, in public and at times in private, that she was even in a relationship with the photographer) but also her writing. Moser—who is gay and was born in 1976, forty-three years after his subject—is never sanctimonious or judgmental when discussing “the sexuality of which [Sontag] was ashamed.”

He is empathic throughout, detailing, for instance, the very real dangers she faced owing to her lesbianism during the protracted custody battle for her son, then nine years old, with ex-husband Philip Rieff, who charged that “her relationship with Fornés made her an unfit mother.” (After Sontag won custody in early 1962, she never again spoke to Rieff, who died in 2006.)

Moser refers, with admiration and compassion, to this journal entry from December 24, 1959, the year Sontag divorced Rieff, whom she married in 1951, shortly before she turned eighteen: “My desire to write is connected with my homosexuality. I need the identity as a weapon, to match the weapon that society has against me.” But despite the enormous changes in views toward being gay that occurred during her lifetime, Sontag “had never been able to shed the attitudes that prevailed when she was young.” Thirty years after that diary jotting—twenty after Stonewall, two after the founding of ACT UP, one after she met Leibovitz—Sontag published AIDS and Its Metaphors, a work Moser describes as “thin, dainty, detached: forgettable because lacking the sense of what AIDS meant to my friends, my lovers, my body.” Her book is clotted with the passive voice—a voice “not appropriate . . . when so many were screaming.” The revolution ignited by AIDS, which included the radical new vocabulary of AIDS activism, would be one “that Sontag would largely sit out: unable to speak certain words,” Moser writes—to say “I,” to come out. AIDS and Its Metaphors “was most remarkable for its irrelevance . . . a first in Susan’s work.”

In writing about the deleterious effects of the closet, Moser on occasion turns to the lexicon of psychology, terminology that he also employs when discussing the profound impact on Sontag of her adored mother’s alcoholism. This mode of interpretation can veer into banal therapy-speak, as in this passage about the effects of her mother’s death, in 1986: “With her went the figure that defined Susan more than any other. So many of her relationships—to herself, to her son, to her lovers—had been shaped by Mildred. The ardent, almost romantic love that she had felt for Mildred as a girl gave way, as she aged, to resentment at the void Mildred had left—a hollowness Susan internalized.” Yet Moser quickly recovers from these soggy sentiments, returning to his robust style and to his scrupulous attention to language. Just like his subject did, he remains ever alert to the imperfections of metaphors, noting that expressions like “coming out of the closet” make the act sound “like a simple, onetime operation—a decision to step out of one room and enter another.” And yet being closeted, Moser continues, had very real effects on Sontag, namely “secrecy, hiding, and shame.”

The closet demands a rupture, a split, the “‘Sontag and I’ game.” In Sontag’s concluding pages, Moser beautifully lays out the rules of that game: “The relation of language to reality was her theme. Neither language nor reality is stable, and in a notoriously turbulent century, no writer reflected their instability as well as Sontag. . . . To a divided world, she brought a divided self.” But within that division, she constantly multiplied; writing in several different genres on an abundance of topics, she “set the terms of the cultural debate in a way that no intellectual had done before, or has done since.” She was limitless. She was I, etcetera and I, ad infinitum.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.