In the summer of 2006, at the peak of an unbearable heat wave stifling most of the Northeast, my parents filed into an unair-conditioned black-box theater in the Catskills to see a summer camp production of the musical Company. A cast of fourteen sweaty adolescent monsters (myself included) stood frozen onstage in khaki trench coats for fifteen minutes before the show began. This was an avant-garde choice we ruminated on heavily in rehearsals: How cutting-edge, we thought, to not even allow the theatergoers (parents) to settle into their seats before letting them know we were about to utterly annihilate the conformity and beige monotony of their way of life. Groundbreaking! Bold! Innovative!

My father, a theater neophyte at the time who was always eager to accumulate trivia, settled in with his program and tried to distract himself from the heat with some light conversation. “You know,” he murmured to my mother (uninterested in theater then, now, and forever), “I think one of the songs from this show is famous.” “‘The Ladies Who Lunch’!” answered a warm, benevolent voice behind him. “Sung by Elaine Stritch.” Then, somewhat conspiratorially, as if not to spook the sixteen-year-old a few feet away burdened with the impossible task of putting over this booze-soaked, acid-tongued aria: “Oh, you gotta listen to her version when you go home—it’s iconic.”

The word has become ubiquitous to the point of cliché—something that was certainly not lost on the actress in question. Theater columnist Michael Riedel’s use of it to describe her, during a 2010 appearance on the PBS series Theater Talk, was met with exasperation. “What’s ‘iconic’ mean?” she crowed. Riedel attempted to redirect the conversation, but Stritch was not to be deterred. “Let’s all level. Let’s all level today and tell each other what ‘iconic’ means,” she insisted, inciting guffaws before the final thrust: “it’s a mouthwash!” Even her rejection of the descriptor merely authenticated its aptness. Elaine Stritch, for many, is a figure unquestionably worthy of veneration, mythic and holy.

Yes, holy. As Ethel Merman once said, “if you wanna do a musical comedy, and you wanna do it right, you gotta live like a fuckin’ nun”—and Stritch was perhaps not as far removed from the cloistered life as one might think. She was staunchly devoted to Catholicism all her life; or, at the very least, staunchly devoted to discussing her Catholicism. She began her notoriously unsuccessful Golden Girls audition by announcing her intent to change the scripted dialogue, citing Catholic guilt over taking the Lord’s name in vain in one line. She then liberally applied the F-bomb to the rest of the text.

And, of course, she had her own vestments. She revered the theater as a sacred space, and her sacramental garments were simple: oversize white men’s oxford shirt, black tights (scandalously sheer in the 1970s, gradually becoming more opaque as decades passed), and no pants at all. Comfortable, effortless, aspirational. (Confession: I am writing this pantsless, and strongly believe it should be read pantsless.) The outfit serves as a litmus test for any potential friendship: Whether a person associates the white button-down/no-pants look with Tom Cruise in Risky Business (philistine, wrong, straight) or Stritch (cultured, correct, gay-adjacent at least) tells me just about everything I need to know. A theater critic at The Guardian reviewing the London run of Elaine Stritch at Liberty flippantly dismissed its star as “another well-preserved septuagenarian actress,” adding, with almost indignant obliviousness, “in black tights and a shirt who appears to have left the house without remembering to put on her skirt.” Upon reading this patronizing slight against the Signature Stritch Ensemble, I very nearly jumped into the comments on a fifteen-year-old article. I had to defend my diva.

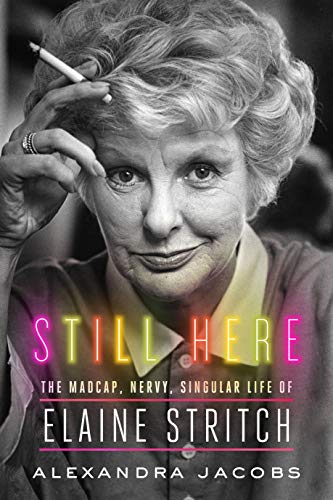

The many reasons Stritch inspired that level of fanaticism are explored in Alexandra Jacobs’s Still Here: The Madcap, Nervy, Singular Life of Elaine Stritch (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27), so engrossing an exploration of its subject that to call it a “biography” feels somehow inadequate. Stritch’s line readings and sense of humor may have been dry, but her life was saturated to the gills: in music, in theater, in glamour, in highs, in lows, and, yes, in alcohol. Jacobs thankfully leaves no stone unturned, making herself a warm and welcoming guide for strangers to Stritch while also diving with fervor into the moments devotees think they know inside and out. It is a meticulously researched romp, a harrowing excavation, an emotional séance, and a glittering family reunion, with the author playing game outsider at the gathering, enthusiastic to find out everything she can.

Jacobs’s rigorous fact-checking of Elaine’s tales (some taller than others) is masterful. The way she incorporates her interview subjects’ contrasting versions of events never undermines the satisfaction of the anecdotes, but rather fleshes them out and encourages us to think about why the storytelling might have been fudged. Embellishments in stories about the beginning and middle of her career seem harmless enough assists in her pursuit of the perfect bon mot, but the lies got bigger as she got older, culminating in the biggest lie of all: that she became sober. The narrative she perpetuated in At Liberty and in interviews was that she completely gave up drinking after a severe hypoglycemic attack in 1987 and remained sober for the next twenty-five years—only taking it up again in moderation in what would be the final years of her life. While the attack did happen, journalist Liz Smith (Stritch’s close friend and confidante for six decades) divulges to Jacobs that even at her soberest, Elaine was still drinking. Was sobriety just a better story? Was the redemptive arc more compelling to Stritch? Or was she afraid, as she got older, that if she didn’t clean up her act, we might stop loving her?

And for all her perfectly performed irascibility, Still Here makes it clearer than ever that Elaine Stritch craved love. Jacobs deftly weaves Stritch’s yearning for validation into the fabric of the book, so that to us, her increased earnestness and emotional availability to the public seem foregone conclusions. One especially devastating moment in the book is a sound bite from theater director and producer Hal Prince, who bemoans that “in the last few years of her career, [Stritch] lost a little of her irony, [her] spikiness”; he “missed it.” It is easy to maintain a commitment to trenchant sardonicism out of doors when you go home to the intimate safety of a loving family. But the only man Elaine Stritch ever married, actor John Bay, died in 1982—and they had no children. Audiences in the later part of her career brought her “a lot of love and understanding,” she told one interviewer. “Especially if you live alone in the world, that’s a marvelous thing to have happen to you.”

So what if she sanded her edges down a bit? She spent most of her life sacrificing sentiment in favor of “another brilliant zinger,” but impenetrability with her public was a luxury she could no longer afford. She had seen the outpourings of adoration afforded less prickly contemporaries like Betty White (of whom she once said—and to whom she later apologized for saying—that “to work with [her] every day would be like taking cyanide”). Jacobs shows us how the maintenance of the public Stritch persona actually necessitated her becoming vulnerable and tender by repeatedly invoking a quote a young Stritch offered a gossip rag: No man “could keep me from a bow.” She had always put the audience’s response above all else, including her personal life; in her later years she simply became more aware that we were her family. She moved back to Michigan, where she was raised, to spend time with her nieces and nephews, but Jacobs heartbreakingly reveals that Stritch felt she’d made a mistake. She thought she was going home to be with “her people,” but once there, she realized show people were her people.

And we felt that. When Elaine passed away, I was a hostess in a West Village restaurant with chic minimalist decor: half “very fancy dentist’s office,” half “Club Monaco flagship store.” I stood all day behind a screen that told me which handsy oil scion or frozen-faced socialite would be gracing us with their presence, but I often minimized the reservation app so I could check various Broadway-related sites. (It should go without saying I was in the midst of a numbing depression.) On July 17, 2014, I refreshed the Playbill homepage, saw the headline announcing Stritch’s death, and began to cry for the first time in months. I overheard a coworker ask what was going on. “I think her grandma died?” I laughed through my tears. I loved her. I loved her the minute I watched her bellow “STOP SCREAMING” as she listened to an unsatisfactory take during D. A. Pennebaker’s documentary of the Company cast album recording process. I loved her for the rules she broke; I loved her for not living like a “fuckin’ nun.” I thought she’d live forever. It was hard to understand in the immediate aftermath of her death that I had not been wrong.

Nearly thirteen years after his unfortunate introduction to Company, my father, now a theater aficionado, recommended that a friend visiting London see the gender-bent revival of the show. His pal emailed him just before showtime. “People around me are freaking out about some big song Patti LuPone is gonna sing?” My dad responded almost immediately, the student becoming the master: “It’s ‘The Ladies Who Lunch.’ It’s an ICONIC song that was originated by Elaine Stritch—ANOTHER ICON!”

That word again, I hear her bark in my head. But we give the word meaning when we use it about someone like Elaine Stritch—because there is no one like her. An icon transcends the personal. She represents redemption for many of us who struggle to believe we are worthy of it. Stritch is a religion of resilience, the patron saint of perseverance. She must be talked about in the present tense because her presence is not gone. It reverberates from the swanky halls of the Carlyle and the Savoy to dingy dorm rooms of theater nerds introducing each other to their favorite performances. She’s still here, dammit. And that’s “iconic.” Is that fucking “level” enough for you, Elaine?

Natalie Walker is an author and actress.