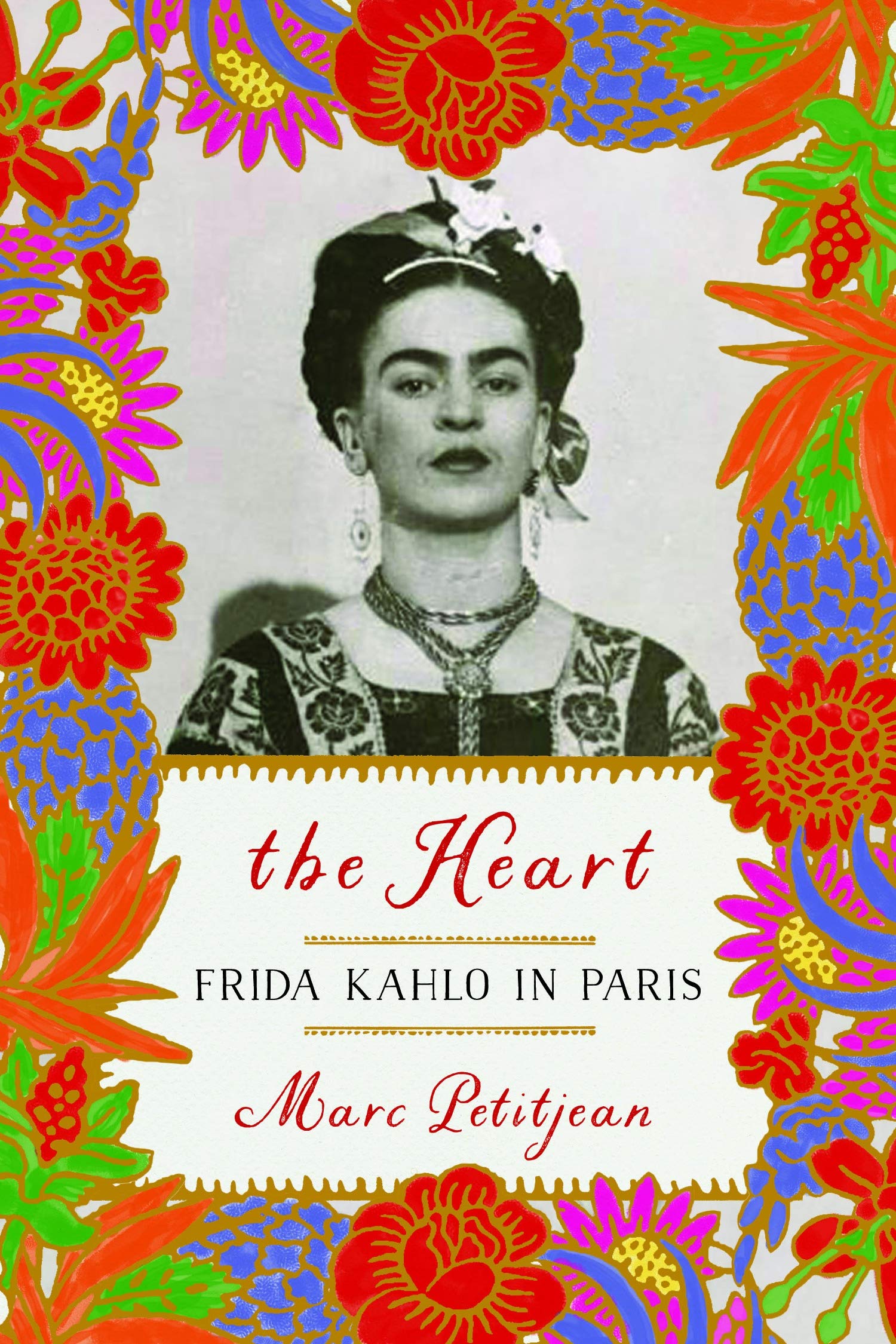

It’s the second week of March in Paris, and COVID-19 still hasn’t shut the city down. I am staying at the Hotel La Louisiane, the haunt of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Cy Twombly, and more—an oddball historic dive in the heart of the Sixth Arrondissement. I spend my days retracing the steps of literary and art icons and reading in cafés. I’ve been asked to write about The Heart, Marc Petitjean’s new book about Frida Kahlo’s life in Paris in 1939, and it seems to haunt me at every step. I walk over the Seine by the Louvre, which was just closed down, and find myself staring at the Hotel Regina Louvre, which I had just read about. I spot the gilded statue of Joan of Arc that Kahlo was delighted by—Kahlo felt an affinity with her, it seems—and I imagine a scene the slender biography in my book bag has depicted: Kahlo breathlessly dashing out of her sixth-floor room and jumping into André Breton’s car for another dinner party she is destined to be disappointed by.

I think about how although I’m partially disabled I didn’t take my cane on the trip, and how in one account Kahlo tells her lover she does not want her disability visible when he suggests a “walking stick”: “I’d rather suffer like a beast of burden than show my disability.” And there is a deliciousness in the way Kahlo rejects Paris in these pages—as in my own life. I complain about the French on social media; I think about Kahlo’s bottomless complaints about them too (“You have no idea the kind of bitches these people are”). She, like me, has left behind some heartbreak; the love of her life, Diego Rivera, has cheated on her, with her sister Cristina of all people, and is in the process of filing for divorce. She puts her energies into a commission in New York—a painting depicting the suicide of American actress Dorothy Hale—and has an affair with photographer Nickolas Muray. She seems to anticipate being altered by Paris but does not yet know how. Even though her circle includes Man Ray and Picasso and Dora Maar and Kandinsky and Duchamp and Breton, one of her most significant and lesser-known admirers will be the real reward of her time there: Michel Petitjean, who happens to be the author’s father.

By the end of my trip, reading The Heart left just as much of an impression on me as Paris itself. This crisp, concise, radiant gem of a book is a delight all the way through, whether you see it as a yarn of multigenerational heartbreak and longing, a beautiful and unlikely father-son chronicle, a classic artist-muse love story, or a cautionary tale about the most obsessively rendered city on earth.

We come to understand that the author’s father has just as much claim on the title, The Heart, as the painting it refers to: Kahlo’s famous 1937 self-portrait, a distillation of anguish and emotional dismemberment. Kahlo gives this work to Michel as a parting gift, and it hangs in the house Marc grew up in without his knowing a thing about its history. When a Mexican writer contacts Marc, he discovers his father didn’t just know Kahlo but had an affair with her during what the book calls “one of the best episodes of her life.” Imagine realizing well into middle age that your father was Frida Kahlo’s briefly but intensely loved paramour!

There is indeed a case to be made that Kahlo’s Paris period is a high point of her life. There, she is able to shed being “Mrs. Diego Rivera.” She is one of the hand-plucked Surrealists of Breton’s group—though reluctantly—and even there she’s an outlier worthy of special attention. As a result, Kahlo, whose legacy was revived in the 1980s and ’90s by feminist artists and critics, is often championed for her independence of spirit and iconoclasm. These qualities seem to have ripened most during her couple of months in Paris, a period Petitjean notes is rarely written about but is, of course, of immense importance to him as he tries to understand both the artist and his father.

Part of the miracle of this memoir is that the author makes his father seem as alluring as Kahlo. “The truth is, it now occurred to me that I knew very little about my father’s life,” he admits, and this mystery carries us through the delicate tangles of the narrative. It’s hard to pin down who Michel Petitjean was, even for his son, as Michel “apparently had no aspirations for a career but wanted a dynamic life among artists, intellectuals, and various political figures.” In the end, after many vocations, he would spend several years in a Nazi camp for collaborating with the Resistance. His life was undoubtedly interesting, but just as Kahlo’s outsize reputation as an artist miraculously manages to seem secondary to her affair with Michel in these pages, his role as her devoted and passionate lover somehow becomes our only concern in The Heart.

We also fall in love again with the irreverent, brilliant Kahlo, who is both charming and insolent in every anecdote. She feels Breton’s accommodations and manners are beneath her and ends up sexually entangled with his wife, Jacqueline Lamba (Breton gets to watch). And there is much delight to be had in Kahlo’s repeatedly expressing her disdain for French culture, especially its artistic circles. “I [would] rather sit on the floor in the market of Toluca and sell tortillas, than to have anything to do with those ‘artistic’ bitches of Paris.” (Bitches seems to be her favorite word for Parisians!) Indeed, the French seem to misunderstand her; the poet Robert Desnos says to Petitjean’s father at one point, “Your friend’s pretty, she could have stepped right out of a display at your Museum of Ethnography.” But we are assured Petitjean is “more attracted to her personality and her culture than her exotic ‘ethnic’ appearance.” In normal circumstances, this would seem shaky, but given the character of Michel, we buy it. Both Petitjeans gain our trust so fully that we don’t question their Occidentalist magnanimity at certain awkward points; while France and the French are belittled by our French author, Kahlo’s Mexico is championed as a center for the arts. “Mexico had no need for surrealism to exist. In fact, the opposite happened: surrealism hoped to be regenerated by its contact with Mexico.” Because Petitjean allies us with Kahlo, we can take or leave Paris, as if it were a city that just provides the gilded frames and the marble halls for great art. In the logic of The Heart, we know the soul of art must lie elsewhere, whether it be Mexico City or even New York City. Everything for Kahlo falls comically, disastrously, fatefully short in France except love.

While Adriana Hunter’s translation reads sturdily, occasionally Petitjean gets a little ahead of himself as he conjures overzealous fantasies: “She spends a whole afternoon in her nightshirt by the misted window, tracing shapes with a finger and softly singing a Mexican lullaby. A house, faces, trees, and an animal appear by turns on the pane. She erases them as she goes.” The author is far more successful when he approaches his subject like the filmmaker-documentarian he is, questioning what he does not know: “I try to picture the evening when the lovers first go into Marcel Duchamp’s bedroom. . . . Is it my father who turns the handle and opens the door? Are they holding hands?”

The Heart is an explosive who’s who and illuminated gossip rag about the greatest Surrealists, and the reader gets to bump into many unlikely icons, from Leon Trotsky to Elsa Schiaparelli, just pages apart. But even in this company, our lovers steal the show. Only in the last few pages do we get a sense of the author as a person in his own right. While we know that Marc Petitjean grew up in the same house as the enigmatic painting, we don’t discover how it shaped him and his career until the very end of the book: “Frida’s painting had opened the way for me: if I chose to, I was free to express in shapes, colors, and metaphors the things I could not formulate with words.”

As I made my way through a still bustling, though soon to be silenced, Paris, and back to New York, facing an uncertain future of quarantine that I’m still in all these weeks later, I again thought of Kahlo. Most likely, Petitjean’s book describes her last carefree days, just before the Second World War. Kahlo’s final years, until her death at age forty-seven, were dominated not by love or art but illness, as Petitjean gently reminds us. In this volume, we get to bask in the potent splendor only a figure like Kahlo, and those who dared to love her, could gift us.

Porochista Khakpour is the author of several books of fiction and nonfiction, including the essay collection Brown Album(Vintage, 2020).