In Murals of New York City, all of the Big Apple’s bygone eras seem to blend together. On the walls of Neoclassical courthouses and Art Deco airports, hallowed hotel bars and brick borough halls, we see the Rockefellers and Roosevelts still running things, and the Astaires, the Barrymores, and the Fitzgeralds forever flitting around. People smoked in restaurants, and artists—apparently—had studios in the attic of Grand Central Terminal. Graffiti didn’t yet have a name. The New School was still new, as was the New Deal. The Works Progress Administration paid for everything. It’s the Gilded Age, and the Jazz one, too; there’s a renaissance in Harlem and an industrial postwar boom, all at once.

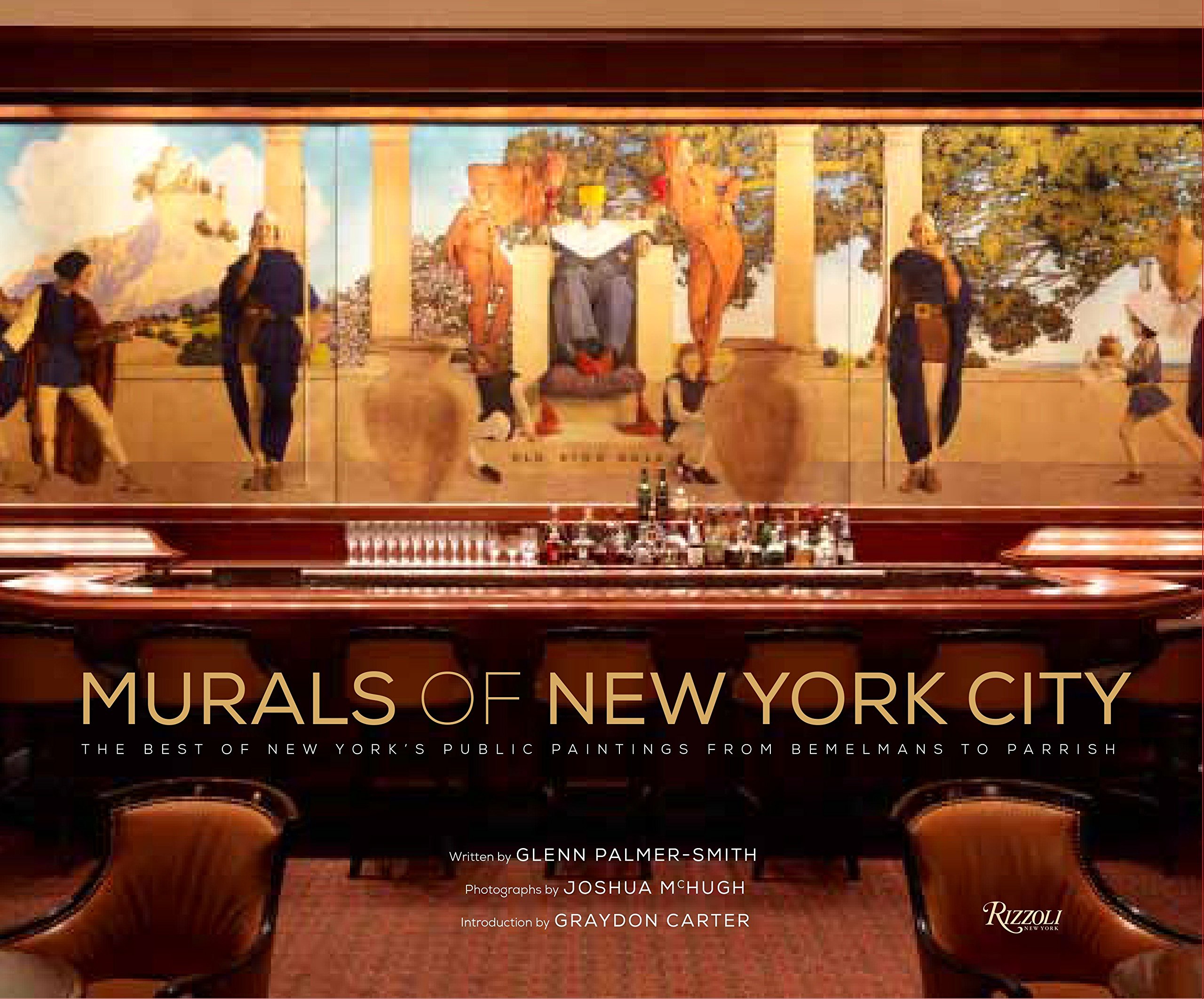

Documented by the architectural photographer Joshua McHugh, nearly fifty murals at thirty-three sites sprawl across the book’s wide spreads. The pictures are factual and digitally pristine, showing the paintings in situ inside sparkling lobbies, soaring rotundas, and lamp-lit restaurants. James Brooks’s Surrealist tribute to Daedalus, da Vinci, and the Wright brothers curls across the circular walls of LaGuardia Airport’s Marine Air Terminal, floating above a tiny Hudson News and a blocky bust of the eponymous mayor. Howard Chandler Christy’s puckish fantasies of frolicking, naked wood nymphs coat the walls of the Café des Artistes, brimming to the edges of the restaurant’s dark brown wainscoting and evergreen booths. (Below, the gleaming curves of empty wineglasses look more breasty by the minute.) At the American Museum of Natural History, William Andrew Mackay’s lurid, Fauvist lionizing of Theodore Roosevelt’s African escapades serves as the backdrop to a dramatic clash between two towering dinosaur skeletons. Attilio Pusterla’s panoramas of the city’s bustling harbors seem to preside over the jurors’ waiting rooms at the New York State Supreme Court, even if a few of their vistas are now ventilation grilles.

Captured and compiled this way, the murals reveal a past in which art was much more ingrained with architecture, with a night out, with a vision of the American Way. Many of the projects in the book were funded by a federal government that believed in a painting’s power to shake the country from its Depression. Art was meant for the walls of everyday public life. And yet McHugh’s images also eerily evoke New York’s unprecedented present. Save for Grand Central and Lincoln Center, almost every site is pictured without people. The Morgan Library is vacant. Nobody sits at the King Cole Bar. The music room at George Washington High School, blessed by Lucienne Bloch’s wraparound fresco, contains only classroom chairs. In Rockefeller Center’s deserted lobby, a lone security officer is surrounded on all sides by Time and American Progress, José María Sert’s colossal ode to the men who built America. Dwarfed by the bulging muscles of these Brobdingnagian figures, the guard sits at the long desk and stares straight ahead, the single remaining spectator of our titans of lore.