ONE APRIL MORNING in 1973, just before dawn, a ten-year-old Black boy and his stepfather began to run through South Jamaica in Queens. A white policeman had pulled up in a Buick Skylark behind them, the crunch of the car’s wheels on the pavement interrupting the quiet semidarkness. Thinking the mysterious car contained someone who wanted to rob them, Clifford Glover and his stepfather fled. The cop, Thomas Shea, pulled out his pistol and fired into the boy’s back, killing him almost instantly. “Die, you little fuck,” Shea’s partner, Walter Scott, was recorded saying on a radio transmission, though he denied it was his voice. Later, Shea claimed that he fired because Clifford—a fourth grader—had brandished a firearm at him, though no gun was recovered from the scene.

For more than a year, the trial was a major news story, dying away only after the policeman’s acquittal in court—a verdict rendered, unsurprisingly, by a jury composed of eleven white men and a single Black woman, Ederica Campbell. Campbell was one of the few voices against acquitting Shea, but, perhaps out of fear of reprisal from the majority white jury, she voted with them. “They almost killed me,” she reflected bitterly, “and I almost killed them.”

The verdict infuriated Audre Lorde, who heard it on the radio as she was driving home in New York. She was so outraged that she pulled the car over and began to do what she often did when she needed an outlet: write in her poetry journal. Out of her rage came “Power,” one of her most visceral poems about police brutality.

The poem was full of pain—something Lorde had always felt was necessary to convey in art. “I have a duty to speak the truth as I see it,” she famously declared, “and to share not just my triumphs, not just the things that felt good, but the pain, the intense, often unmitigating pain.” The poem begins with an extraordinary declaration: “The difference between poetry and rhetoric / is being ready to kill / yourself / instead of your children.” Real life is poetry, and, in turn, pain. The poem quickly shifts, in typical Lordean fashion, into a surreal stanza of horrific images: the speaker “trapped on a desert of raw gunshot wounds,” with the image of a “dead child,” his blood “the only liquid for miles.” The desert, which was first associated with gunshot wounds, becomes “whiteness”; living in a racist, white-majority world is, for Lorde, to live in a desolate, despairing landscape punctuated only, all too often, by the murder of Black people. The poem then shifts into a journalistic description of the moment Clifford loses his life and the unjust legal aftermath. At the end, Lorde, feeling helpless with fury, imagines in graphic detail taking out her wrath on an elderly white woman, finishing the poem with perhaps the most painful observation of all: that her act of violence, unlike a white person’s, would be described as just the ordinary, senseless violence that Black people do to well-meaning white folks, while the officer is given a pass. The poem’s shifts from surreal imagery to a starkly realistic description of the scene of Clifford’s death are intentionally jarring, capturing how nightmarishly disorienting real life can feel for a Black American who knows that, at any moment, a white cop can decide to end your life.

I find myself returning to Lorde more these days. As a queer woman of color from the Caribbean, I enjoy Lorde’s unabashed embrace of her identities: Black, woman, lesbian, an American born to West Indian parents. Her work is full of anger, but also of love and lust—for Lorde believed, rightly, in attacking the idea that women should be ashamed of erotic desire or seeking out any kind of pleasure. And while it remains all too common for women of color to have to point out the racial blind spots of many white women’s feminist practices, Lorde, who was an unabashedly intersectional feminist, was calling out white feminists’ racism decades ago.

But it is her rage, most of all, that I keep returning to, a fire fueled by the blood of so many murdered by white Americans in plain sight. Since her death in 1992, Lorde’s anger has become one of her signatures, and that anger—raw, gutting—speaks with extraordinary directness to contemporary America. Black women who express rage have so frequently been dismissed as a crude trope, the “angry Black woman,” and justice for Black women murdered by the police is unequally distributed, if they receive any justice at all. Lorde refused to hold back her fury and sorrow, and this makes her writing feel strikingly vital now.

2020 has become a funereal, frustrating year filled to its bloody brim with Black death—not the bubonic plague, but something more literal, the diseases of police brutality and a viral pandemic that has disproportionately affected Black Americans. I think of how poignant it is to read “Power” now: joy, in that Lorde’s poem, for all its pain, has beautiful lines, but also a sense of quiet disappointment, as slow and suffocating as the pull of quicksand, that so little has changed between then and now.

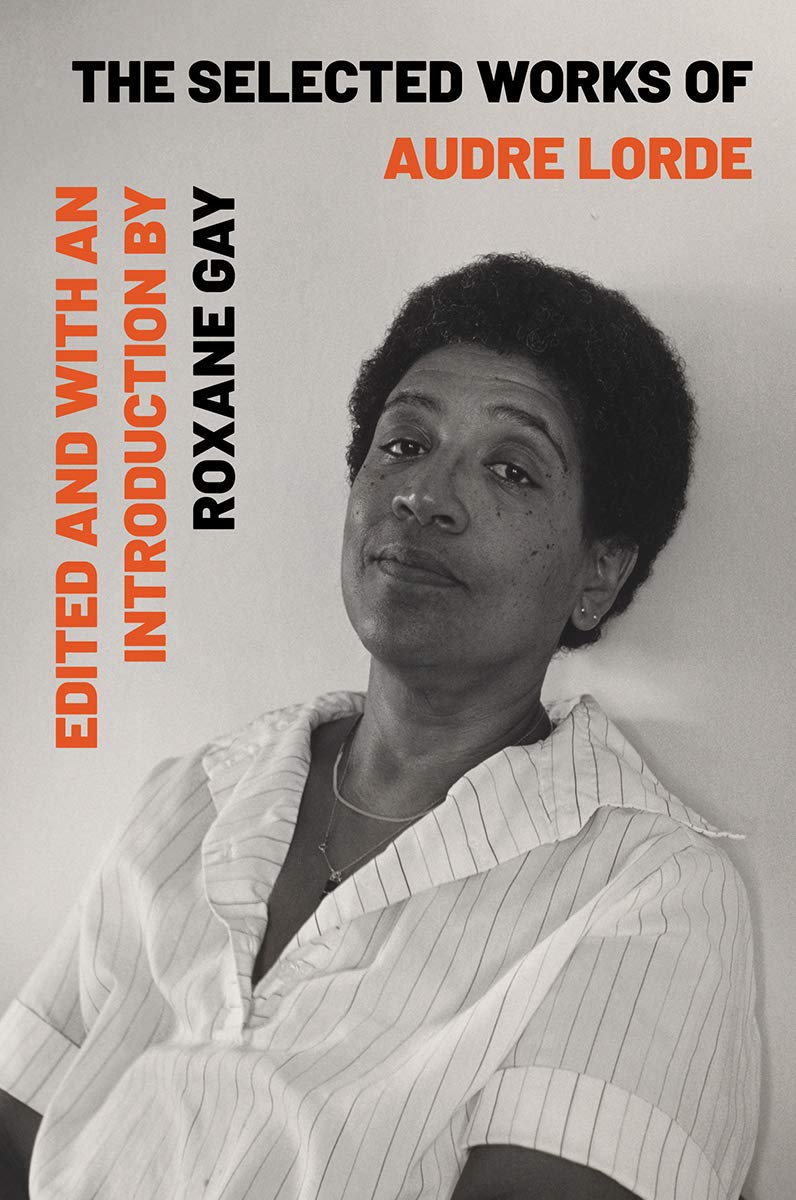

“POWER” IS ONE of the poems in The Selected Works of Audre Lorde, a new, well-balanced anthology of prose and poetry featuring many of Lorde’s greatest hits and a new introduction by Roxane Gay. The collection contains many classic essays and lectures that her fans will recognize, like “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” “Uses of the Erotic,” “The Uses of Anger,” and the much-quoted “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Readers primarily familiar with these works will find a compelling selection of her verse, as well as some of her more personal writing about her childhood and about the cancer that would eventually lead to her death at age fifty-eight. “My Mother’s Mortar,” a chapter from Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), is a fine example of Lorde’s memoir writing. The anthology lacks any of Lorde’s notable public conversations, like her famous talk—published in Essence in 1984—with James Baldwin about what Black men fail to realize about the struggles of Black women; still, the new book is a good place to begin, particularly for readers yet to discover Lorde as a poet.

Lorde’s prose has become popular to cite in activist circles, but her poetry is far less quoted. This is unfortunate, given that Lorde saw herself more as a poet than anything else, on and off the page. Her poetry and prose explore similar themes, the most prominent of which include antiblackness, queerness, whiteness, eroticism, and feminism, and her very understanding of poetry was bound up with how she understood what it meant to write and live as a woman with many intersecting identities. What makes her poetry special, to me, is how it captures the way that these themes feel: the dreamlike horror of racism, the sudden erupting quality of rage when one has simply seen too much pain, or the subtle yet vast ways in which women can express desire for each other.

When Lorde was not writing poetry, she was memorizing it, and she sometimes literally spoke in verse. “I used to speak in poetry,” Lorde reflected in Mari Evans’s 1984 anthology, Black Women Writers (1950–1980): A Critical Evaluation. “People would say, well what do you think, Audre. What happened to you yesterday? And I would recite a poem and somewhere in that poem would be a line or a feeling I would be sharing.”

“Power” was hardly her only poem to describe Black death; indeed, the dead populate Lorde’s poetry almost as densely as the living. “Passing men in the street who are dead / becomes a common occurrence,” Lorde writes in “Conclusion,” a poem from her 1973 collection From a Land Where Other People Live. Her poems form a sort of aesthetic necropolis for the Black dead, becoming, in this way, both elegy and eulogy for the fallen.

In “A Poem for Women in Rage,” which describes the shocking moment that a white woman pulls a knife on Lorde—the white lady calls her a “Black Bitch”—the poet seems to compare America to a “deathland,” reflecting, not unlike at the end of “Power,” on how she, too, thought about using a blade. Despite the clarity of her rage, Lorde still feels lost in this country where murder is all too ubiquitous:

In this steaming aisle of the dead

I am weeping

to learn the names of those streets

my feet have worn thin with running

and why they will never serve me

nor ever lead me home.

Lorde’s radical transparency about her anger—in particular, her imagined instances of violence against whites—was typical of her, and this impulse to share also informed her writing about desire. This is perhaps clearest in one of my favorite essays, “Uses of the Erotic.” Here, Lorde wishes to reclaim the term “erotic” from how it “has often been misnamed by men” as a synonym for pornography or “plasticized sensation”; for her, embracing the erotic meant allowing ourselves to feel as deeply as possible. Expressing oneself so directly—especially as a woman—can still feel transgressive, and this makes Lorde’s unapologetic revelations feel bold, even startling, now.

To read Lorde is to encounter a flame that is unashamed to be one, even in a world that fears fire. To read Lorde is to begin the work of unmanacling and decolonizing one’s mind, to begin the urgent work of learning how all things—identities, prejudices, systems, histories, desires—are linked. To read Lorde is to learn as much as to unlearn, to embrace the oft-maligned characteristic of being blunt, to feel a woman’s uncensored rage about the many Clifford Glovers that are being killed in America by white officers who desire little more than to dominate and destroy a Black body. To read Lorde is to encounter a writer whose vision of a murderous, ravenous America is, at its red core, all too similar to our own, its hunger for Black bodies and blood still just as chillingly insatiable now as it was then.

Gabrielle Bellot is a staff writer for Literary Hub and an instructor and editor at Catapult.