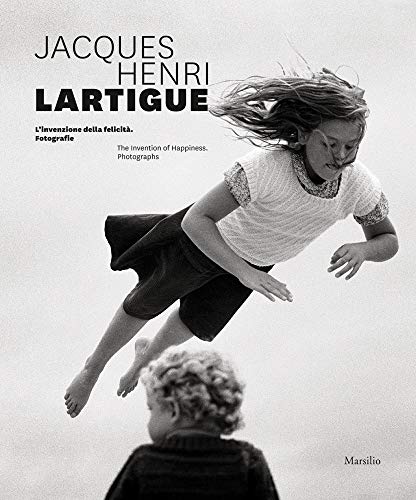

JACQUES HENRI LARTIGUE (1894–1986), an artist whose work seems to come from another world but in reality comes from the past century, captured that era’s experience of speediness, of beauty, of carelessness, of fun. Born in fin-de-siècle France, Lartigue started shooting film as a child. Though he thought of himself as a painter first, Lartigue became famous for photographing auto races, early aviation, beachside horseplay, and society women on the Bois de Boulogne. He pioneered techniques for capturing heart-stopping proto-parkour, like a quick dandy jumping over some lazy chairs, or, in My Cousin, Bichonnade, 40 rue Cortambert, Paris, ca. 1905, a well-dressed woman hurtling down a steep outdoor staircase. She could be flying, or falling—it’s uncertain whether the next frame will be a graceful landing or a bone-breaking crash. In their focus on old-world leisure, complete with men in Manet-ish straw hats and women shadowed by parasols, Lartigue’s early pictures recall the Post-Impressionists; in their buoyant, gentle anarchy, they anticipate François Truffaut by way of Jean Vigo. Jacques Henri Lartigue: The Invention of Happiness, Photographs collects more than one hundred images from JHL’s own albums, including fifty-five unpublished works and eye-catching color prints from later in his career (he also experimented with autochrome color as early as 1912). Lartigue went mostly unheralded until 1963, when the Museum of Modern Art (New York) granted him an exhibition and a Lartigue series appeared in the issue of Life magazine that covered John F. Kennedy’s killing. Soon after, he became one of the most influential photographers of his day, though his name doesn’t come up much anymore. Someone like Richard Avedon is unimaginable sans Lartigue (indeed, the younger man compared seeing the MoMA show to first encountering In Search of Lost Time). Both men, attracted to affluence, admire the heedlessness of the upper classes. But unlike Avedon, whose pictures always seemed a bit hungry for status—even as they deflected that wish through wan irony—Lartigue seems truly amused by the Bertie Wooster–esque beau monde. As such, the photos feel joyful in a way that seems impossible to pull off now.