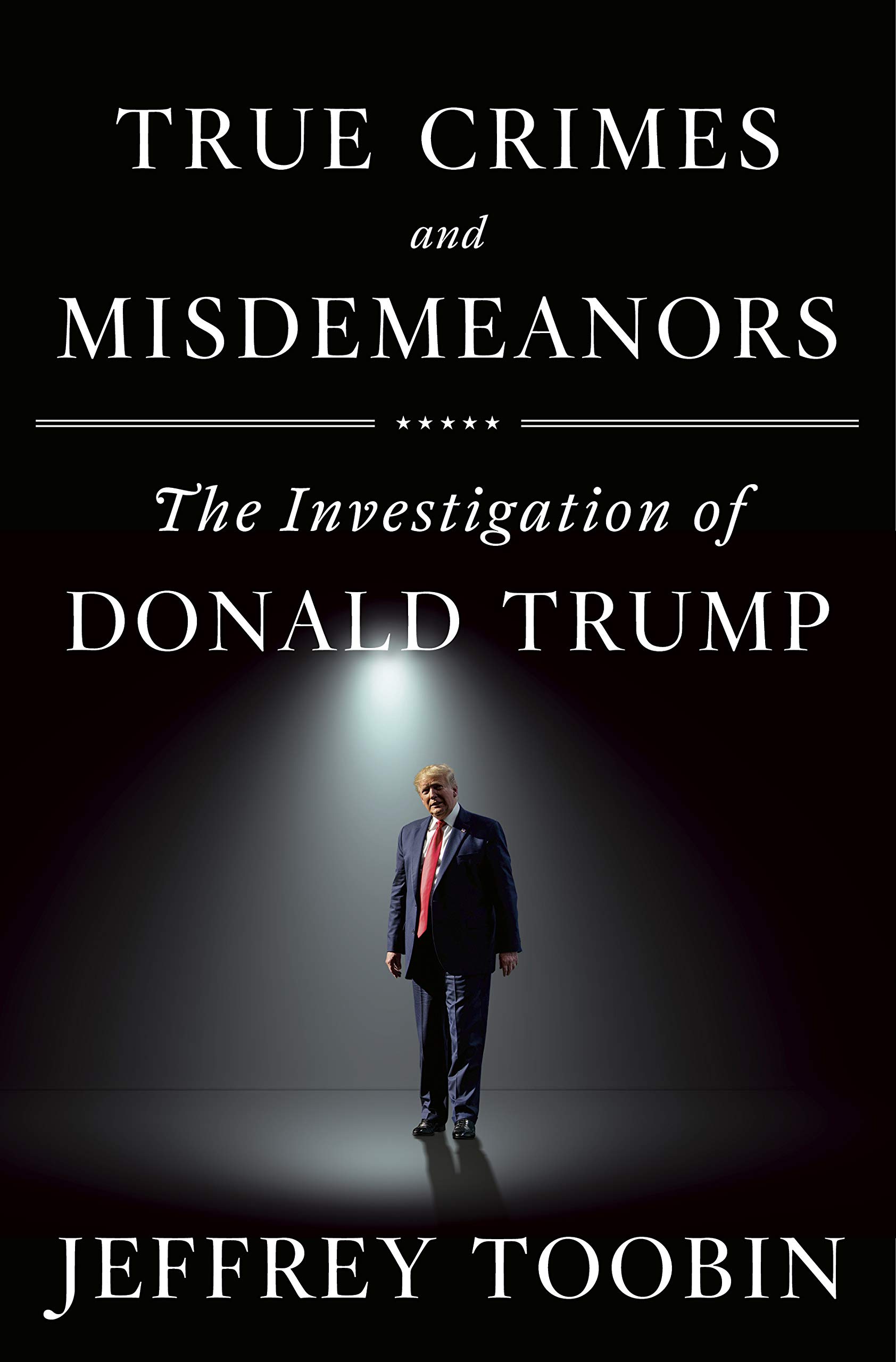

THE MARKETING COPY describing True Crimes and Misdemeanors as “a real-life legal thriller” sets up unfair expectations for a book rehashing recent news. The outcome is already known: Trump is still president, despite two investigations examining shady dealings with Russia and Ukraine. Early in his presidency, with liberal media at a fever pitch comparing him to twentieth century European dictators such as Mussolini and Hitler, it seemed that liberals really believed the headwinds of collective outrage would topple Trump before the end of his first term. As of this writing, two weeks before the national election, Trump has survived not only the two investigations covered in Jeffrey Toobin’s detailed account, but storms of controversy around brutal immigration measures, white-supremacist vigilantism, sexual assault, the uncontrolled pandemic, and so on. Meanwhile, the Democrats’ constant but useless harrying of Trump has allowed him to style himself as a permanent insurgent, assiduously attempting to drain the DC swamp even as new degradations pour in.

Despite this, longtime reporter Jeffrey Toobin does his best to establish narrative tension, for example with the punchy fragments that end almost every chapter, cliff-hangers with no cliff: “For the moment, few people outside the insular world of white-collar prosecutors and defense lawyers had heard of Andrew Weissmann. But that was about to change.” Or, my favorite: “Cipollone wanted to talk about the House, and Schiff wanted to talk about Trump—if he could escape from the dentist’s office.” (House Intelligence Committee Chair Adam Schiff had to delay a root canal during the Ukraine hearings.)

Any writer would struggle to make this material thrilling. Even if there were some suspense or mystery around the outcome, the topic is the bureaucracy of governance. This dry terrain is not just the context of the book’s events, but also the field of struggle on which Democrats chose to battle Trump. As in the news cycle, so in the hardcover book: the chosen areas of investigation are so circumscribed, and the fine details of the potential crimes so difficult to grasp, that they slip from the attention almost as they enter it. Toobin takes us back to the 1787 Constitutional Convention to explain why the legal provisions for impeachment are so vague about what apart from foreign interference constitutes “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Still, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s narrow interpretation reveals what her party is able to collectively care about. Popular sources of real outrage—the Muslim ban, the emboldened KKK cops, the stolen children, the ICE camps, all the people broken on the anvil of the state for their simplest desires—are invisible from the point of view of the law.

Shorn of his real abuses, the Trump of institutional Democrat antipathy appears as a kind of jester figure, the holy fool of the tarot card, bravely teetering forward into eternity like a buoyant stock market. He has a raw, desperately intuitive clarity about others, scanning the field of the social like a resting apex predator. Everything about Trump’s language is more alive than the dry social technocracy articulated by the heroes of this book—centrist politicians and government lawyers. “[Pelosi] doesn’t pray. . . . I doubt she prays at all. These are vicious people. But . . . they stick together. Historically, I’m not talking now. They stick together like glue.” He is right, in his way: the class unity of the bourgeoisie is the basis of the modern nation-state, a gentlemen’s agreement prone to falling into disarray when the gentlemen fail to agree.

Although Robert Mueller, who led the Russia inquiry, is a Republican, “there was no denying that his staff had a clear Democratic orientation,” and Mueller himself became increasingly unpopular among Republicans as the investigation went on. Toobin regrets Mueller’s obscure technical language, his lack of media savvy, and, ultimately, his failure to hold Trump accountable. But despite this failure Mueller is depicted sympathetically, as a too-cautious but fair stalwart of a better era, fated by his upright character to go too high when they go low. Toobin describes him as “an object of bipartisan support, even veneration,” “the only person with the gravitas and experience to win acceptance from Democrats and Republicans,” “a straight shooter with no political agenda.” Toobin is more ambivalent about the same aspiration to ideological vacuity in fired FBI Director James Comey, whom he depicts as a limelight-loving fop: “He was a Republican appointed by a Democrat, but Comey always aspired to float above politics.” These two examples suggest that bipartisanship might not always be an absolute good—might even be a fetishization of political weakness in the face of a passionately partisan enemy, or a sign of an attenuated capacity for dissent. But Toobin does not have the stomach for these considerations. We are left with Mueller as a figure whose flaws and strengths are hard to disentangle: a principled man for whom political principles are always subordinate to class unity. The latter priority, and not the search for truth, is the real basis of the law.

For the most part, Republican and Democrat politicians are people with a lot in common, bickering colleagues in the management of our permanent decline. (No big surprise but there is no mention in this book of how Democrat leaders crushed Bernie Sanders’s campaign, which might relativize their horror at electoral manipulation.) To idealize bipartisanship beyond grim strategy, you have to believe in a golden mean, a shining center in which policy, cash, and lives are traded freely. This faith, espoused by centrist Democrats and moderate Republicans, is based on a fantasy of tough but fair experts making hard choices—sorry, buddy, had to bomb your village! Fantasy has little purchase in a chaotic, flailing, hyperviolent world system, but any unpleasant evidence of this chaos can always be neatly combed back into the dream of order. Toobin relates how the Ukraine investigators, led by Adam Schiff, delved into material on Richard Nixon, yet another self-interested, incompetent president who besmirched the reputation of the self-interested, incompetent state. Everyone on Schiff’s team got their very own copy of Jimmy Breslin’s book on Nixon, How the Good Guys Finally Won: Notes from an Impeachment Summer. Through a leaden sleight of hand, the moral of Watergate is that good guys win, not that bad guys are in charge.

Even before Mueller’s investigation fumbled the ball on the charge of criminal conspiracy with Russia, Democrat anxieties about electoral interference were arguably more piety than praxis. Democrats are proud of their record of interference in foreign elections, including Ukraine. They have no issue with manipulation and geopolitical dealmaking as long as these activities promote lofty abstractions like good governance. This has historically been justified, at least since 1945, with a vision of America as the muscular conscience of the world. But, between the lines of legal detail and scandalized anecdote in this dull book, a world-historical vertigo is tangible: Trump, a crappy person propelled into the presidency by blond ambition and daddy’s money, makes concrete the pathetic flimsiness of American moral authority.

Trump’s desire for loyalty reminds his adversaries of the Mafia, which stands for threat and violence but also a kinship structure, a form of counter-power. The latter seems to cause the real outrage. Toobin quotes Comey: “To my mind, the demand [for loyalty] was like Sammy the Bull’s Cosa Nostra induction ceremony—with Trump, in the role of the family boss, asking me if I have what it takes to be a ‘made man.’” Comey thinks that personal loyalty is the wrong kind of loyalty, and promises loyalty to the truth instead. Toobin one-ups him: “Comey’s loyalty was not to the law or to the procedures and hierarchies that supposedly governed his conduct and those of his predecessors.” Comey is selfishly attached “to his own conception of the truth and of the right thing to do.” But law doesn’t need loyalty, it has the police.

Trump and his allies ventriloquize popular impatience with the pathological evasiveness of political discourse. Their open ease with lying has made it possible for them to tell more truth than ever before, contributing to an atmosphere of constant, almost meaningless revelation and upheaval. In a notorious outburst, former White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney reveals the “obvious truth” that US foreign policy always involves quid pro quo: “We do that all the time with foreign policy. . . . And I have news for everybody. Get over it. There’s going to be political influence in foreign policy.” Mulvaney cited the US aid withheld from Guatemala on condition of reducing migration—a Congress-approved policy. Trump’s liberal enemies seem, in this light, like prissy bureaucrats making ever finer distinctions in order to assuage their sense of their own historical rectitude. They still speak in the carefully controlled language of management and expertise. But Trump’s strange gift to the era is that his wildly personal, plain speech has abolished the brittle, alien mode of address that used to characterize politics. Despite Biden’s promise to return things to normal, we will probably never go back to the deadening professionalism peddled during the brief decade or two when history was over. In a rare moment of self-reflexivity about the alienating effect of managerial non-speech, Toobin frets about Democrats’ overuse of the phrase “quid pro quo”: “It might have been a mistake to devote so much attention to a phrase from a dead language.” The language of liberalism feels as dead as Latin.

Toobin’s carefully researched, detailed prose slides by in unerotic shades of gray, occasionally studded with glittering Trumpisms—insults and exclamations harvested from Twitter, public appearances, and private recollections. The activities of lawyers and government functionaries express the opacity of traditional politics, while the sprinkles of Trump-language are funny, scandalous, and often accurate. “It’s an excuse by the Democrats for having lost an election that they should have won,” he summarizes the fixation on Russian interference. Toobin confirms in a parenthetical, “Trump, like virtually everyone else, thought he was unlikely to win the presidency in 2016 and thus would be returning to the real estate business.” One of the many weaknesses of Mueller’s approach, Toobin suggests, was that he excluded Trump’s finances from his investigation on the basis that Trump’s motive was simply to win the election, and that he wasn’t trying to forge alliances that would facilitate future real estate deals in Russia. The investigation never got to grips with the extent to which Trump absorbed the presidency into his business interests.

Toobin narrates Mueller’s investigation as a contest between two styles of governance, traditional and ostentatious. According to this account, Comey’s tendency to show off, his love of attention, paved the way for Trump’s derangement of the executive. Toobin’s advocacy for tedium starts to feel like a direct expression of the problem facing the Democrats, which is that they are boring to the point of immorality. Does Pelosi, who “[begins] every day shortly after dawn with a visit to a Washington hair salon,” know that human life is full of wrenching intensities? How about Schiff, who was thrilled as a young man to land a “dream job” as a federal prosecutor? It starts to feel like Trump’s crass gluttony might be preferable to the joyless managerial propriety favored by the center-leaning lawyers Toobin praises.

THESE SELF-STYLED DEFENDERS of democracy operate the law like a Tesla driving through a slum. They believe in the law profoundly, all the more because they are, to some degree, above it. They even communicate in its language—in a vignette of office life among Mueller and his staff, Andrew Weissmann playfully hangs a stolen Amtrak “Quiet Car” sign between his and Jeannie Rhee’s office, prompting Mueller to joke, “I believe that a federal crime has been committed here.” As high-level administrators of America’s vast network of courtrooms and prisons they deal in life and death, but they don’t seem to conceptualize the objects of their legal work as people. They are assisted in this by a vision of the law as an abstract entity that lives in a structure adjoining life. The law next door is always dressed up as principle, despite the trickery it demands as tribute.

Weissmann, we learn, built his reputation on bully stunts such as “inviting witnesses to come in for informal office interviews, and then threatening them with prosecution.” Manipulation of this kind is the substance of prosecutorial work. Occasionally Toobin, a former lawyer, zooms out a little to educate readers on the law: “Defendants plead guilty and cooperate because they think that going to trial will result in a conviction and a longer sentence. For this reason, prosecutors thrive on fear.” In the USA, more than 90 percent of criminal cases are resolved in this way, through fear. Terrorized defendants take multi-decade plea deals in the hope of one day seeing freedom. The president is aware that the legal system runs on manipulation and violence. When Trump’s fixer, Michael Cohen, was raided by the FBI, Toobin writes:

“Trump knew enough about the criminal justice system to recognize the Cohen raid for what it was—a massive show of force designed to convince Cohen that resistance was futile and that pleading guilty was his only option.” Toobin praises these power moves as tactical genius. As an abstract ethical good, the law as such supposedly bears no relation to the ruinous practices of policing and incarceration, even if the lawyers investigating Trump use the same techniques that have warehoused millions of poor people in horror conditions. “For good prosecutors,” writes Toobin, “professionalism will always trump partisanship.” But prosecutors are partisans of a depraved prison system.

“It’s tempting to see the struggle between Mueller and Trump as one between good and evil, and there is much evidence to support that view,” writes Toobin, citing their “contrasting experiences with Vietnam.” Mueller devoted four years of his life to that brutal, pointless, shameful war; Trump, on the other hand, did the right thing and stayed home. Even the war’s primary architect, Robert McNamara, came to think of it—albeit far too late—as terribly wrong. But in this book, service to a terrible wrong indicates strength of character. Toobin disdains Trump’s off-color joke that trying to avoid sexually transmitted infections while dating was “my personal Vietnam” because it fails to express the proper reverence for obscene slaughter. This is just one example of the wacky moral universe that Toobin seems to inhabit, in which mass murder, torture, and rape are all par for the geopolitical course, but rude tweets are beyond the pale.

The book’s incoherent vision of Russia is evidence for Trump’s contention that Russia conspiracy theorists are sore losers rather than good detectives. At times, Russia is understood as fully continuous with the Soviet Union: “Mueller’s career in the Justice Department stretched back to the days of the Cold War against the Soviet Union, so he hardly needed lessons on the malign intentions of the government in Moscow,” writes Toobin. It’s not exactly as if the Cold War never happened, but as if we are in an eternal 1990. At least Trump, who has attempted to peddle his vodka brand and construct luxury buildings in Russia, is aware that it is a rapaciously capitalist country.

Toobin is not a fan of the late Roy Cohn, Trump’s favorite lawyer and “one of the leading red-baiters in the country” with a “vindictive and unethical style.” But the deep impact of US anti-communism is forgotten by the time it comes to introduce former Ukraine ambassador Marie Yovanovitch, whose “parents enjoyed the dubious distinction of having fled two tyrannies, the Communists and the Nazis.” The belief that communism and fascism present two equidistant extremes, two twin perversions of the proper routine of politics, is also the font of liberal sanguinity about capitalist violence. Bad to kill all those people, but on the other hand, communism is not an efficient way to mass-produce plastics! As the center collapses, self-declared moderates all over the world continue to field various walking essences of twentieth-century nostalgia to defend themselves against what they imagine as the twentieth-century rise of fascism redux. They have retreated from reality. In focusing on constitutional wrangling, Toobin misses the point: the Constitution is only powerful to the extent it reflects real relations of power. The law is inside the building.

The book abuts directly against the present—I was surprised to remember, through the 2020 fog, that the investigation into Trump’s dealings with Ukraine concluded in late January of this year. Toobin appends a prologue and an epilogue where he discusses the pandemic directly. “It will take years to assess the full toll of the coronavirus. . . . Trump’s feckless indifference in those early days cost thousands of American lives.” If liberals want to avoid their own brand of feckless indifference, they will have to fall out of love with the grand abstraction of the law. They will have to take their chances in the hinterlands beyond the imaginary middle.

Hannah Black is an artist and writer. She lives in Brooklyn.