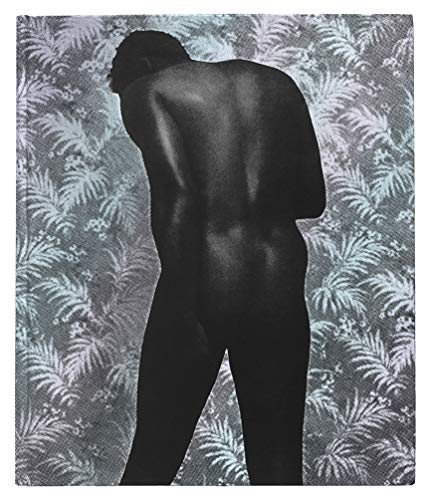

SOON AFTER ARRIVING in New York in 1973, Ming Smith sold two pictures to the Museum of Modern Art (New York), becoming the first Black woman to be granted entrance into house Szarkowski. It was an honor she took in stride; she already knew she was good. For the next thirty-plus years, she turned out exceptional work in a broad range of styles, influenced by everyone from Claude Monet to Romare Bearden to Katherine Dunham to Zora Neale Hurston: portraits of Black cultural luminaries; documentary images of life in American cities; dispatches from around the globe; and richly allusive, kinetic shots of jazz musicians that read as a collaboration rather than a capturing. This impressive new monograph covers every phase of her career and contextualizes her work with contributions by Namwali Serpell, Greg Tate, Yxta Maya Murray, and others. Smith, like her colleagues in the Kamoinge Workshop, depicted Black stories from the inside, exponentially expanding the narrow photo canon. Still, it’s only recently—beginning in 2010, with Smith’s inclusion in a MoMA survey—that her achievement has been widely acknowledged. Smith’s approach, which emphasized self-determination and an ethics of care, shaped both the form and content of her photos. As Arthur Jafa notes in a conversation with Tate: “The technical parameters of what she’s doing are, in fact, structured by a commitment to being in [the] spaces that Black people occupy. The spaces that are underlit.” Long exposures of blurred bodies in motion, low-light chiaroscuro, wiry swirls of light, and dreamlike multiple exposures augmented with daubs of hand-painted color—Smith’s aesthetic feels outside of time even as it pinpoints an essential moment. Whether she’s shooting a Pittsburgh pool shark sizing up the table or Sun Ra on his way to a higher plane, Smith exemplifies the art of constant, refined attention. Or, as she puts it, “The image is always moving, even if you’re standing still.”