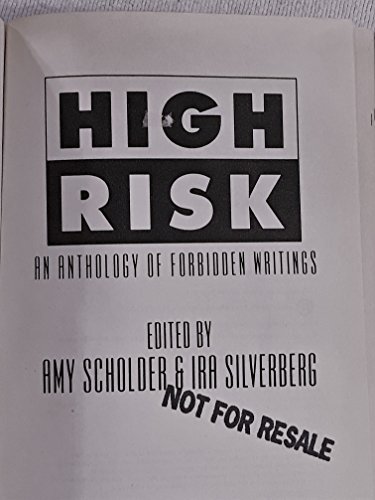

I PICKED UP HIGH RISK: AN ANTHOLOGY OF FORBIDDEN WRITINGS in Trident Booksellers & Café on Newbury Street in Boston in 1991 (when you could still smoke cigarettes while you read and drink bowlfuls of cappuccino), because Kathy Acker was in it and I idolized her—though she confused me with all her code-switching, gender-floating, language-bending, anti-narrative raucousness. Maybe I idolized her because she confused me. William S. Burroughs was in it too. He confused me but not in a way I was sure I liked. I was determined to keep trying though; Burroughs had literary street cred.

High Risk had street cred. “The otherness of the junkie, the homosexual, the sadomasochist, the criminal, the prostitute, the marginalized,” writes Ira Silverberg in his introduction. “This is what High Risk explores.” The collection crosses genre, favors spirit of message over artistic cohesion. Its contributors are hip, angry, fully uncompromising. I might accuse my past self of having wanted it more as an accessory than actual reading material. (I was certainly aware that knowing who Gary Indiana, Karen Finley, Dennis Cooper, and David Wojnarowicz were made me more sophisticated.) Except that I did read it—compulsively. I read it because it was exciting and bold, sometimes incomprehensible, always terribly explicit about vulnerability, and really, with the exception of the Kathy Acker, unlike anything I’d read before.

“I don’t believe reading a book will change my life,” writes Amy Scholder in her introduction, “or anyone’s life, but rather that by opening up my imagination, some part of my inner self can be suddenly available to me.” On the cusp of adulthood, I read it, I realized, in the spirit of self-discovery. Looking for those clues. What were my thoughts about fist-fucking? It seemed important to know. Essex Hemphill’s “scrotal sack full / of primordial loneliness” left me cold; then just three pages on in the same long poem, “Heavy Breathing,” I read this stanza and felt my heart tear:

At the end of heavy breathing

for the price of the ticket

we pay dearly. Don’t we darling?

Searching for evidence

of things unseen.

I am looking for Giovanni’s room

in this bathhouse.

I know he’s here.

Why this and not that? How can longing be so complicated, artful, and inarticulate?

I read Mary Gaitskill and Dorothy Allison for the first time in this anthology—tortured and touched by the raw brutality with which they wrote about the sexuality of young girls: “I became ashamed of myself for the things I thought about when I put my hands between my legs,” writes the child narrator of Allison’s “Private Rituals,” “more ashamed for masturbating to the fantasy of being beaten than for being beaten in the first.” Dennis Cooper’s psychotic sexual predators hover, companionably, near Kathy Acker’s philosophical Father/Artist: “It might suffice, but I don’t know for what, for a painting of horror to break down and through its viewers’ perceptual habits so that they can see what their minds and hearts refuse to see and what is.” Excrement and urine, which I don’t like much, feature highly in the collection. One of my favorite stories, Lynne Tillman’s “Diary of a Masochist,” opens with the line, “Remember when you pissed on me in San Francisco?” I forced myself past it, intrigued by my own resistance, and discovered a love story so vexed it made realism feel obsolete. I was a more curious reader then. As compelled by the question “Why do I hate this?” as I am today by the question “Why do I love this?”

High Risk was formative. Everything I learned subsequently in literature class—Pasolini, Sade, Genet—contextualized it. Which didn’t make me less tongue-tied when I moved to New York City and met one of its coeditors, Ira Silverberg, in real life. He was a celebrity to me. He was pleased and only a little astonished when I finally managed to stammer out my declaration of love for High Risk. (Little rabbit, new to the city, transgressive literature under her arm.) Decades have passed and I’m over the shyness. Now, I turn to Ira every so often and remind him that I knew of him before I knew him because of High Risk. I tell him that we’re due for a new edition. I ask him what he thinks would constitute high-risk literature today. At which point we both fall silent, and look glassily into the middle distance.

There’s a reason for that helpless response—or, rather, two reasons. The first and more fraught reason is that taboos operate much differently in 2021 than they did in 1991. Much of what was sexually transgressive and “other” at the time of High Risk is no longer celebrated in the margins of culture. In the name of progress, it’s normalized. Whereas other taboos explored in High Risk—the sexuality of a victim of incest, for example, in Allison’s “Private Rituals,” or the casual racism of middle America in Gaitskill’s “Action, Illinois”—are rhetorical and emotional land mines. Again in the name of progress, explorations like these are dangerous because they shouldn’t be normalized. Narrating victimization is no less important today, and yet it has a new system of rules that don’t tolerate the shock and swagger of a label like “forbidden writings.” In other words, some of the taboos of High Risk aren’t taboo at all anymore, and others are more.

The second reason is quainter, and one that seems much more apparent in hindsight. So much so that I feel a little shy broaching it. I was twenty when I found High Risk, ripe for shock and swagger. But the world was too. The late ’80s, when presumably most of the work collected in High Risk was being written, was the height of the culture wars—spotlighting in particular Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ and Robert Mapplethorpe’s bondage series “X Portfolio.” Arguably the biggest pop star of that moment, Madonna, published an X-rated coffee-table book titled Sex (1992), a follow-up to the R-rated documentary feature film Truth or Dare, in which she gave a blow job to a bottle and Sandra Bernhard complained about stray bits of toilet paper when performing cunnilingus. Paris Is Burning (1990) swept the awards in the documentary category. The subculture of transgression was trending in 1991. If you consider the Whitney or the New York Film Critics Circle to be “establishment,” it could even have been considered mainstream. “Transgression” was being grappled with beyond Avenues C and D. Which to some extent may have mitigated the riskiness of High Risk and, by extension, explains why there isn’t a simple contemporary parallel to be found—at least not in terms like “risk,” “transgression,” or “taboo.” The question, “What would be in a 2021 version of High Risk?” maybe isn’t the right question.

There is something else, though, that’s also specific to that moment—something that’s possibly more important than the mainstreaming of “deviance”—and that’s the HIV/AIDS crisis. In 1991, the World Health Organization estimated that ten million people worldwide had been infected and there was not a cure in sight. High Risk contributors Essex Hemphill, Cookie Mueller, Manuel Ramos Otero, John Preston, and David Wojnarowicz all died of AIDS-related illnesses. “High Risk is not an AIDS book,” writes Scholder, “but of course . . . ” Of course, in retrospect, it is. All of the blood, shit, and semen that flows in these pages, the persistent sense of irreality, the swagger that stands in for anger and grief, the drugs and violence that numb—everything that makes it, in fact, hard to read—are also its importance thirty years later. It is a monument: this is what that moment felt like. It would be trite to update it.

Minna Zallman Proctor is the author of Landslide: True Stories (Catapult, 2017).