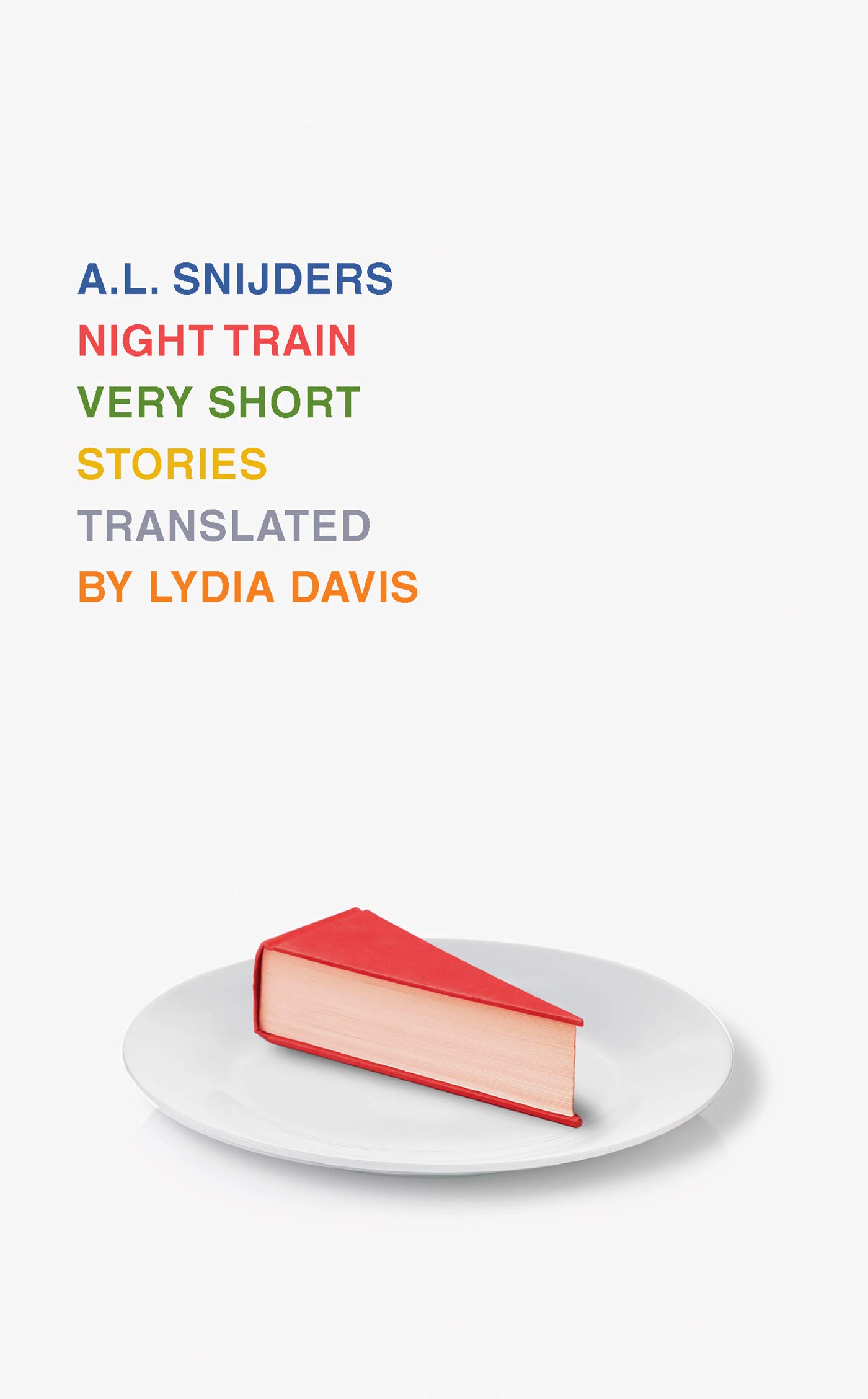

“WE FEEL AN AFFINITY with a certain thinker because we agree with him,” writes Lydia Davis in “Affinity,” one of the shorter stories in her collection Almost No Memory (1997). Yet according to Davis, it wasn’t a sense of kinship that led her to the zeer korte verhalen (zkv’s), or “very short stories,” of the beloved and prolific Dutch author A. L. Snijders (1937–2021). Rather, it was a sense of fairness: if her books were being translated into Dutch, then she should translate a work from Dutch into English. It would be no small challenge, since she would have to learn the language as she went along. Snijders seemed a good choice: “I liked [his] straightforward approach to storytelling, his modesty and his thoughtfulness,” Davis explains in her introduction to Night Train, a new English-language collection of his work, for which she selected and translated ninety-one of the three thousand stories Snijders wrote in his lifetime. Like Davis, Snijders can compose rich, complex life studies in just a handful of sentences, extracting profundity from the absurd, and vice versa. Their sensibilities are so well matched that one can hardly imagine a better translator and interlocutor for him than Davis; that kinship is likely why this collection feels so smartly, exquisitely wrought.

“Shoe,” Snijders’s very short story about his very short stories, describes the origins of the form. In his telling, he was an unnaturally born writer: a terrible student, incapable of crafting lengthy sentences, though he had an excellent memory and, as one might infer, a keen, near-reverent attention to a day’s events, backgrounds, and players. Although brevity, for him, is a “virtue of necessity,” it is not, in and of itself, the intended hallmark of his work. Short is merely short. A true zkv exhibits the dynamic effects of such shortness on the act of writing—how it compresses the mechanics, squeezing out any extraneous yammer, tightening the connective tissues, leaving a reader more room for reading—or, in Snijders’s words, for “autonomous cerebration.”

What also distinguishes the zkv is a story’s detectable departure from the event on which it is based, a slippage that Snijders likes to imagine is clear to his readers, though he admits that he’s the only soul who can actually sort his facts from his fictions. (For the sake of brevity, I’ll forego trying to parse the author from his first-person narrator.) “Blunt reality is my source,” he declares, and in “Shoe,” he shares a few details from an overheard exchange between a husband and wife. Snijders recalls hearing the man declare that a life must be lived with “passion.” “That awful word,” his wife grumbles, “it can still make our daughters furious.” This incident eventually seeds “Passion,” a tale of daughters, unnamed and unnumbered, who rebuke their father’s views on the subject and so leave home, twice, for the sea. In “Christmas 13,” which appears later in the collection, he borrows a few lines from the journals of Jules Renard (1864–1910), perhaps as surrogate, or food, for his own thoughts: “The truth exists only in the imagination. Choice in truth lies in observation. A poet is an observer who immediately recreates.”

A dream about losing a glass eye. On the social arrangement of a throuple of swans. Recollections of an Italian meal eaten with a Scottish drummer. At his best, Snijders sends a reader shooting across one of his loosed synapses. None of his zkv’s are ever tied up neatly. “I often think about a photo that I’ve never seen,” begins “Suckling Pig,” a sidewinding story that describes a picture of a dapper man holding a young pig under his arm—a man who, years later, would become the father of poet Charles Simic. Even an unseen image can move the psyche, and this one prompts Snijders to remember how his mother described the boy next door “squealing like a pig”—an expression Snijders realizes he doesn’t hear much anymore—when the boy’s father would hit him, and how his mother didn’t know who to call for help. The particular flicker of his prose—how it cuts across the clocks of an old photograph, an unsettling image from childhood, and finally his present reflections—also illuminates something of the elisions, of what is forgotten and cannot be resuscitated, no matter how precisely words may conjure the past. “Time slips away and takes language with it,” he notes.

Night Train doesn’t include the dates of Snijders’s stories as a collection typically might, an editorial choice only worth mentioning because for many years, writing was reputedly a daily practice for him. As well, he had a popular weekly Sunday spot on the Dutch station NPO Radio 4 for more than a decade, during which he would read something he’d written just for his listeners. In these and other ways, his stories mark time—of days, thoughts, memories, encounters—yet as he himself believed, it is fiction that renders time immaterial. In “Geese,” he recalls a teacher who had strict opinions about the value and place of invention, thinking, for example, “that film was not an art because you could not decide what you as spectator were looking at.” For Snijders, being correct proves less valuable to an author than being indelible. “If he had confined himself to the prescribed curriculum, he would have disappeared into the mists of time,” he writes in the final lines of this story, which feel like an appropriate elegy for Snijders himself, who passed away in June. “That will also happen, but only after my death, for I sometimes think about him. And as long as I do that, he is still alive.”

Jennifer Krasinski is the editorial director of Artforum digital.