KIDS TODAY! Is fashion all they care about? It’s a driving force on TikTok, and rare is the person under twenty-eight who doesn’t have something we’d call “style.” But the medium of fashion writing has left the kids tragically underfed. In fact, it’s left people of every age starving. It isn’t that no one is talking about it; teenagers on Twitter are practically building an archive of the 1990s-era work of the cerebral Belgian designer Martin Margiela and the provocateur Jean Paul Gaultier, and even your normie uncle has an opinion about whether men should wear skirts. It’s more like we’re at a buffet and there are endless chafing dishes of the same meat and potatoes. Most contemporary fashion writing is obsessively semiotic. Maybe because we live in conspiracy-theory times, fashion writers seem to think there is a secret agenda behind every politician’s outfit. Or celebrities tell us: “I’m a celebrity, and my dress has a big skirt, because celebrities are people too.” Writers dutifully decode how the bigness of the skirt reflects the irrational bigness of the fame machine. This school of thinking has Barthesian origins but often reads as propaganda, making the writer a coconspirator in promoting the beliefs of the clothing wearer. Presumably, ascribing political and social meaning to clothing rationalizes fashion (which is a totally irrational animal), and justifies it as a subject worthy of everyone’s consideration. But the upshot is that most people who care about style, or are at least aware of it, have a very narrow view of its effect on us, even though we sense that clothes are really up to something weird. And for those who are obsessive about it—yeesh. We are all Martin Margiela girls in a Devil Wears Prada world.

But what if there were a world where the devil . . . didn’t wear Prada? What if the devil, like these kids themselves, wore Margiela? And what if he wasn’t just wearing it . . . what if he actually were Margiela?

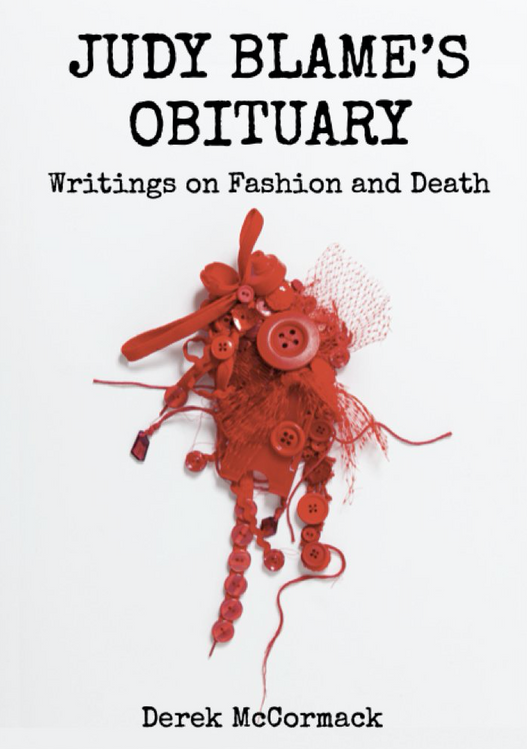

Children, such a world exists, in the beautiful and twisted mind of writer Derek McCormack. McCormack’s twenty years’ worth of essays, profiles, and interviews are collected in a new book, Judy Blame’s Obituary: Writings on Fashion and Death (Pilot Press, $16). McCormack started as a fiction writer and has published several works of pretty outrageous stories, including The Well-Dressed Wound, a Civil War–era novella about Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln attending a fashion show hosted by the Devil disguised as Margiela; and The Show That Smells, in which the Surrealist couturier Elsa Schiaparelli is a vampire and her rival Coco Chanel a vampire hunter (don’t you love this guy?!); and an ode to country’s gnarly-twangy underbelly, The Haunted Hillbilly, which imagines the rhinestone-fabulous designer Nudie Cohn as a vampire—“the Thread Count”!—who torments a dim-witted Hank Williams.

Often when fiction writers take on fashion, they seem very scared, and it doesn’t really work out. McCormack, on the other hand, loves the terror, and runs right at it. His approach to fashion is a gothic gross-out, an Edward Gorey illustration of the movie Superbad. Like fashion itself, it is offensive and demented, and McCormack embraces with hysteric dryness the Freudian notion that fashion is a conspiracy of queerness, insisting that black humor, like a black dress or suit, looks great on any subject. In The Well-Dressed Wound, AIDS . . . is . . . funny? In a piece on the origins of The Show That Smells, McCormack reflects on a $170 bottle of perfume that I’ve seen elsewhere described as embodying “nobility and strength”: “Dzing! by L’Artisan Parfumeur. It smells like shit. It’s an animalic, a type of perfume with a fecal fragrance. When I sniff myself, I get a whiff of wet fur and asshole.”

Here is his own raison d’être: “Fagginess is what I write about. I focus on things that fags love: fashion and death. Think about it: all fags wear fashions—I’m wearing some!—and all fags die—I’m dying!” Indeed, Judy Blame’s Obituary unfolds like the rooms in a gothic-horror mansion, with McCormack as the mutant verison of Gilbert Adrian, the golden-age-of-Hollywood costume designer responsible for The Wizard of Oz, dressing his subjects in dazzling little ensembles of phrasing. Here’s the stiff drawing room where he goes to do a regular junket interview with Balenciaga designer Nicolas Ghesquière about his new perfume but falls into a sorcerer’s mirror of introspection about what it means to make “futuristic” design. Here’s the crypt where he raises the sequin pioneer Herbert Lieberman from the forgotten beyond. There’s the powder room where he ponders Freudian nutjob Edmund Bergler’s 1950s-era theories about fashion as an expression of queer men’s inherent misogyny, and crowns the late Thierry Mugler, who dressed women as clamshells and kitties, Bergler’s “nightmare.” (“What isn’t Mugler’s fetish? The man has a fetish for fetishes. Or is it a fetish for fetishes for fetishes? Or is it a fetish for fetishes for fetishes for fetishes?” If you’ve seen Kim Kardashian in those wasp-waisted latex feats of fabric logic, you’ll understand what he means by the last one.)

McCormack meets a lot of spooky characters along the way: he titles an essay on the artist David Altmejd, who uses vintage and costume jewelry in his gruesome-chic sculptures, “Hairy Winston.” He calls Margiela “a grave digger.” When he reports, it’s not as a detached observer but as a starving vampire: watching, waiting, hungry, ready to gorge himself on blood. Elegance may be refusal but pleasure is bingeing. Each subject feeds McCormack as much as his reader. He also feeds himself—he is a solipsistic journalist. An interview with Altmejd (“the Wolf Man”) saunters through subjects like models at a couture show, each little digression on the right way to style a brooch, or the role of taste in fashion and art, or the purpose of mannequins, an exquisite and fully formed fantasy of craftsmanship and exhibitionism.

Actually, though, fashion is solipsistic, and it is personal. It’s about desire and denial. It’s psychological warfare, baby! This is the alternative perspective that the focus on interpreting signs and symbols in fashion misses. Freudianism is out of, um, fashion, but McCormack sees it as inescapable when it comes to looking at clothes. And he’s right! After all, why do so many people, young people especially, buy so much fast fashion when the case has been made so clearly that it is environmentally unsound and exploits female and nonwhite laborers? Why do so many people in such bad outfits have such rigorous opinions on what stars are wearing when they win awards? Why does a generation that champions the politically correct worship an appropriation-obsessed designer like Gaultier? The surge in interest in fashion has emerged concurrent with the prioritization of identity politics, which makes it easy to see why symbolism is so appealing. But couldn’t the case be that fashion doesn’t merely tell the world who we are and what we believe, but allows us to define those things for ourselves—and that we lie, a lot?

McCormack insists on the naughty and disturbing, where even fashion lovers have sanitized or insisted on self-seriousness. Look at his treatment of Margiela, who is often considered an intellectual dreamboat, a cool and collected Antwerpian whose obsession with found objects and “humble” or unexpected materials is the bygone pinnacle of fashion’s current obsession with mixing high and low. But McCormack sees him as a Dr. Frankenstein, a “mad scientist” chopping up garments to make new little monsters. Not sterile and cool, but funked and weird. In his magnum opus essay on the designer, “Maison Monster Margiela,” he writes:

Zombies are corpses who come back to life. Hair rotting. Suits wormy. But zombie chic isn’t just for cadavers. In 1997, Margiela grew cultures: bacteria, yeast, and mold. He dyed them yellow, green, and fuchsia. With a perfume atomizer he spritzed them on suits and dresses. The clothes had been coated with a mold-friendly medium. Care labels read: Don’t wash. The cultures grew. The dyes spread. The suits stank like the grave.

You can practically hear McCormack licking his lips, tasting blood and dirt and clumps of lipstick. And yet all this darkness comes from a place of love. He doesn’t apologize for his lust or even his interest in the subject, as far too many people who claim to care about fashion do, and he never deigns to suggest fashion is important because it is art, or because it tells us something about “contemporary life.” (Barf!) It’s important to him because it tells him something about him.

McCormack has a way of writing that I can only describe as undead. Like Margiela, he loves garbage, and loves to turn it into something else. But he doesn’t want to transform it so much that you miss out on how disgusting it is. Each of his essays is a séance, bringing together ghosts from past and present to take you somewhere you won’t admit you want to go. He even embraces the hackneyed style of old-school fashion writing, as if he were the snappiest copywriter at the Harper’s Bazaar of a 1940s purgatory: “Margiela experiments with clothes like Dr. Frankenstein experimented with cadavers. His clothes aren’t haute couture, but haute horreur. They’re made for the living. They suit the undead.”

Another garbage collector in McCormack’s pantheon is Judy Blame, the late punk artist who created jewelry out of junk foraged from the banks of the Thames. Like Blame’s jewelry, McCormack’s writing displays all the junk of daily contemporary life, the flotsam and jetsam of the worst parts of town. He says as much himself: “I wanted to be his kind of punk, but had to settle for writing. I think of words as brooches pinned to paper,” he writes in his obituary of Blame. “I think of sentences as shit necklaces.”

Fashion is an airbrush business, so we often forget that these crisp shirts, crystal-encrusted masks, fountains of taffeta, and silk suits are made to encase sweaty, fleshy living forms that eat and shit. Above all, McCormack encapsulates the visceral and disturbing pleasure that comes with appreciating the corporeal nastiness that much of the fashion world tailors out of the bounds of good taste. Guilt is not the only feeling that should come from vanity and indulgence. Camp, after all, is also about the grotesque, the revolting, the downright repulsive. I don’t know that McCormack could challenge Divine’s Babs Johnson for her title of “filthiest person in the world”—but he’d probably rather roll around in shit with her, anyway.

Rachel Tashjian is the fashion news director for Harper’s Bazaar and the author of the newsletter Opulent Tips.