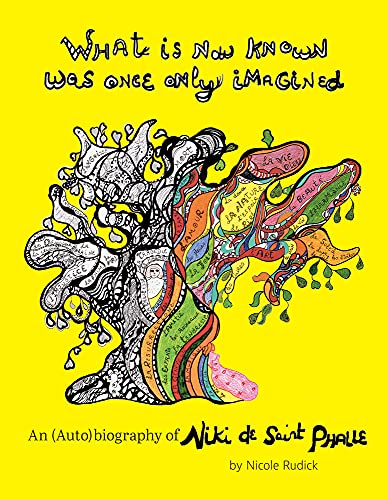

TO TELL THE STORY of another person’s life poses certain challenges to an author wanting to capture their subject in the truest light possible. In the introduction to her ebullient, poignant What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined: An (Auto)biography of Niki de Saint Phalle, Nicole Rudick offers up her strategy for honest representation: “What could be closer to the artist’s voice than the artist’s own voice, closer to her sensibility than that produced by her own hand?” Rudick edited this hybrid volume of text and images, selecting and sequencing Saint Phalle’s own writings and works on paper to tell the artist’s extraordinary life story. “Writing for me is an instrument to think or unravel something I did not know,” the artist reflected in 1995, “unraveling the spider’s web.” The narrative web of What Is Now Known spins—Saint Phalle is not treated, as is often the case in traditional biographies, as a code to be cracked, or a mystery to be solved—to apprehend the artist as the person, and persona, she understood herself to be.

Saint Phalle, according to Saint Phalle, was born on October 29, 1930, to a depressed mother, who told Niki that the doctor attending her birth saved her life, preventing her umbilical cord from strangling her to death. “Danger was present from the first moment,” the artist proclaims in a letter addressed to her mother but written for the catalogue of a 1992 exhibition in Bonn. “I would learn to love DANGER, RISK, ACTION. . . . I would spend my life questioning. I would fall in love with the question mark.” She goes on to tell of her marriage at nineteen to the writer Harry Mathews, of the births of their daughter Laura and son Philip, and Saint Phalle’s subsequent abandonment of her children—“the way men often do”—in 1960 to become an artist. Loosed into “the big wild world,” and with no formal or technical training in art, she relentlessly followed her instincts and ideas, forgoing imitation in favor of willfully developing a hand that was all hers.

A romantic, and a terrific beauty to boot, Saint Phalle loved love, and men were some of her most potent muses. Elemental to her story is Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely, who was, over the course of three decades, her lover, her collaborator, her traitor, her ex-lover, and her husband, while remaining throughout her creative interlocutor. “Niki,” she recalled him telling her, “the dream is everything, technique is nothing—you can learn it.” She credited Tinguely for pushing her to realize in the early ’60s her “Tirs” (Shooting Paintings), a series of reliefs made of paint and foodstuffs secreted beneath a plaster surface, works that she would then execute, literally and metaphorically, with a gun. “It was an amazing feeling shooting at a painting and watching it transform itself into a new being,” she wrote of these firebrand performances that brought her to international attention. “It was not only EXCITING and SEXY, but TRAGIC—as though one were witnessing birth and a death at the same moment,” she added, perhaps hearkening back to her own origin story. In the wake of the “Tirs” came the “Nanas,” for which Saint Phalle is best known: enormous, luscious, multicolored sculptures embodying feminine archetypes.

Saint Phalle’s tale is near mythical by her telling, full of vivid characters and synchronous meetings and extraordinary events; it is also not an altogether happy one. She was plagued throughout her life by acute health problems and suffered unfathomable wounds at the hands of her father, who raped her repeatedly when she was eleven years old. Yet she credits that horrific betrayal for opening her to art. “I learned to live with it and to survive with my secret,” she explains. “This forced solitude created in me the space necessary to write my first poems and to develop my interior life, which would later make me an artist.” Like so many mythical beings, Saint Phalle entrances readers as a model of survival, at times even of a kind of transcendence. As expressed by the artist’s last words in this book: “la mort n’existe pas / life is eternal.”

What we do with our dead and the things they leave behind says a great many things about the living. Regarding the output of artists, for example, one might note how estates are the art market’s clean-burning fuel of choice, and notice the inflated value of objects made by dead artists undervalued in their lifetime. I winced when Rudick used the word “collaboration” in a recent interview to describe her working relationship to Saint Phalle because it is simply not possible to create in cahoots with someone posthumously—end of story. That framework has become the go-to conscience scrubber for those who produce new works from other people’s archives. I recall an exhibition of filmmaker-performer Jack Smith at Gladstone Gallery in 2011, in which three living artists were commissioned to “collaborate” with him by using his work in one way or another to make a new piece. In effect, what was on view were not the products of collaboration, but something closer to estate proliferation (more stuff to sell), and a bid to infuse Smith—who died in 1989—with the most saleable yet least interesting quality of all: relevance. What is compelling about Rudick’s book is that it is something of an antidote to all that, putting forward a form—the “(auto)biography”—in which the two authors are both present and accounted for fairly and correctly. More quietly, What Is Now Known also clarifies editing as a creative act rather than a definitive one. Saint Phalle wrote nothing for this book, and yet this book is written by her. Embracing that contradiction, Rudick enables the artist to speak for herself, as herself, once again.

Jennifer Krasinski is a writer and critic and the digital editorial director of Artforum.