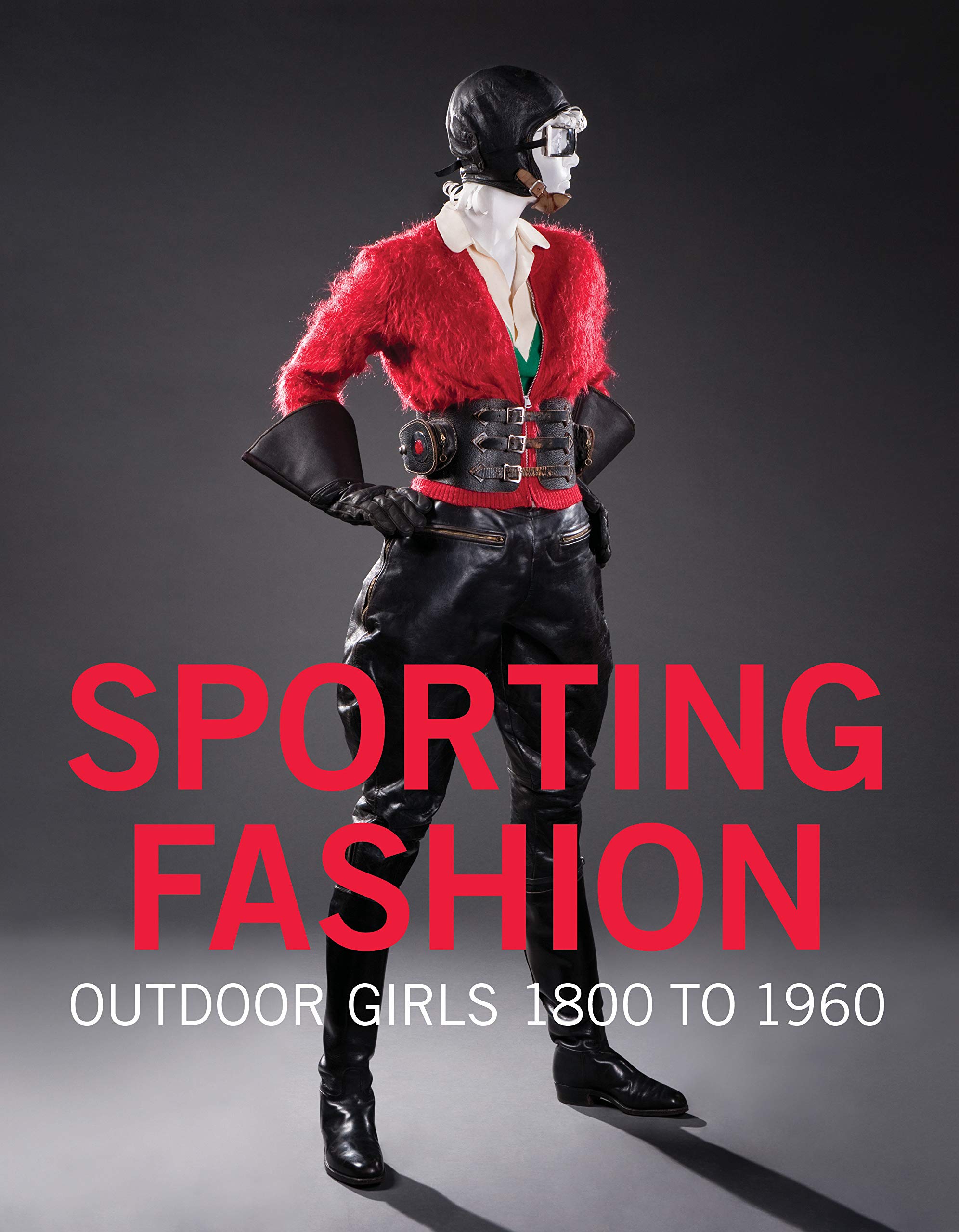

I HAVE REACHED a shocking conclusion after paging through the exhibition catalogue Sporting Fashion: Outdoor Girls 1800 to 1960 (American Federation of Arts/DelMonico Books, $60).

Athleisure . . . is . . . progress!

The ubiquitous yoga pants that people still write into etiquette columns to complain about, the Allbirds sneakers that pad through the corridors of Silicon Valley startups, even the crop tops celebrities don to drink green juice après Pilates—perhaps these are the garments that most unequivocally define modern fashion. Not inventive dresses or breathtaking gowns, but the kind of luxury basics that Karl Lagerfeld once famously derided as a sign that the wearer had given up on life. (Of course, he made many similar garments in the years following.) What if, instead, they meant that you’ve given up on fashion that isn’t designed for an active life?

A traveling exhibition curated by the American Federation of Arts and the FIDM Museum, which this catalogue was made for, traced the ways in which women attired themselves for leisure and competition. (That’s also how you might describe the two modes of being a woman—relaxing and competing.) Clothes for more than forty activities—from ice-skating to suntanning—are represented in its pages, including items from the 1950s and ’60s that begin to look familiar. Remarkably, some of the garments are ones you might still see today, and not even on vintage hounds—a camping outfit comprised of yellow plaid outerwear and rolled-up jeans brings to mind the average richster Angeleno trotting out in her prized Bode jacket. One reason for this is that clothing, through associations with sports and leisure activities, became ever tighter as women earned more freedom, reaching its modern zenith as women were allowed to be more athletic. Or, in the words of the innovative midcentury American designer Claire McCardell, “Sports clothes changed our lives—perhaps, more than anything else, made us independent women.”

The book groups clothes by the activities they were worn for, some of which are still practiced today, like tennis and beach-going and weightlifting, and others which are no longer leisure activities for wealthy women—or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that having costume-like uniforms for ventures like ranching, going on safari, and shopping simply went out of style. Within these groupings, the book constructs a fascinating miniature history of female liberation. In many cases, the looks are aesthetically rich and appealing. Through the book’s sequential sorting, we see the progress of the body revealing itself, either by a pure reduction of fabric—arms or ankles bared—or by garments hewed ever tighter to the female form. “Sporting fashions developed out of necessity and morphed from one era to the next,” the curators reflect in the introduction, as “older, restrictive styles adjusted to fit increasingly active bodies, and innovative modes were designed for emerging games that captured the popular imagination.” It wasn’t that women put on an ice-skating costume with its shorter skirt, or a driving coat with a looser fit, and were suddenly liberated—it was that clothes began to accommodate a larger span of activities and freedoms.

You could also say that these new activities introduced a sense of reason to fashion’s otherwise untamable narrative arc. Fashion in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was primarily motivated by constant novelty, and frivolity—a nonsensical, disjointed progression—was its only purpose. With little else to do, in other words, wealthy women created an urge for change in one of the few places they were allowed to experiment. But suddenly, fashion choices—about fabrics, hemlines, prints—became practical, as women chose clothes for outdoor activities like walking, which they began to see as pursuits. Shoe design—which, across multiple cultures, often became a race toward sheer impracticality—began to take cues from comfortable slippers usually worn in private. Raincoats became necessary. And, soon enough, pants did, too—one chapter mentions competitive “pedestrienne” Emma Sharp, who entered a walking race in which participants traveled 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours; she wore a red-checked pantsuit and a matching waistcoat.

Most fashion historians—amateur and academic alike—think of fashion’s modernization as a movement toward more-masculine clothing. Anne Hollander argued as much in her 1994 volume Sex and Suits. In this telling, progress in women’s fashion meant leaving behind pointless reinvention and embracing the elegance and adaptability of men’s suits, which had changed very little since the 1920s. Sporting Fashion seems to accept this view: women like Sharp adopted menswear to perform better, and the book notes that women’s clothing became more masculine as they gained civil liberties—like the right to vote. But each chapter’s linear structure also suggests another idea: the more fitted and revealing the garment, the more progressive it is. This is clearest in the chapter on clothes for the beach and for water sports, “Making Waves.” The earliest bathing costume here, from the beginning of the 1800s, would make a prairie-dress devotee roll their eyes at the prudishness: a linen shift with a bonnet and slippers, and a wrap around the shoulders. Things get progressively skimpier—pants come in, hemlines go up, and sleeves disappear—until the 1930s bring us something that looks not unlike the offerings at your local J. Crew. Perhaps bathing-suit designers could get away with such scant material because water, beachy air, and sun were already associated with health long before the bikini came into play. But even in the 1870s, commentators were pitching the beach as a place where women could be free from the heavy fabrics of everyday wear; a beach outfit might require seven or eight yards of fabric, whereas the average daywear called for over twenty.

There is no revealing of the body, of course, without someone to see it. The story of the swimsuit getting increasingly smaller is also the story of wearing one, especially on the walk from a teak chair to the water’s edge. There was the expected moral outrage from commentators about the impropriety of these outfits, and an even weirder pervasion—the male gaze—that you can trace from the invention of swimming bloomers to the opening credits of Baywatch. But the more-revealing designs also gave women a new opportunity to compare themselves in even greater detail to other women, including the recently invented class of unattainable celebrities.

It turns out that a lot of sportswear was invented for sitting around in. Or, more precisely, for being looked at, and looking. There are outfits for volunteering (a festive jacket), lounging (a long-skirted off-shoulder two-piece), touring (a silk jacket printed with Egyptian iconography), celebrity stalking (a skirt suit with images of California fantasia like a jodhpur-clad film director), and weekending (a simple plaid skirt and sweater vest that would depress Princess Diana, with a silk scarf printed with victory slogans that the catalogue describes as being “in a more propagandistic mode”). Women could acquire an outfit for “suntanning,” which in the 1930s was a swimsuit with a revealing, cross-strapped back inspired by evening gowns paired with clingy beach pajamas festooned with a print of Ivy League pennants. Palm Beach’s famous “semi-sport,” summer shopping, called for a practical wrap dress by McCardell that accommodated both visiting formal stores and hopping into one’s convertible. This last example is a reminder that practicality is often quickly transmuted and teased into a luxury proposition (fashion tends to do that, as it has done more recently by treating the climate crisis and efforts to increase diversity as trends). And, again, we have to remember that these outfits were developed for nonworking women living on a (at the very least) middle-class budget, for whom outfit changes provided order and structure to days that otherwise filled both Edith Wharton heroines and Sylvia Plath antiheroines with existential malaise.The most revolutionary garment in the whole book is the one likely most familiar to you. In 2018, Serena Williams wore a fitted black Nike catsuit at the French Open, which she discusses in the book’s lovely preface as her own connection to the style innovations that follow in the catalogue. The catsuit was celebrated for its superhero-like fit—Williams compared it to T’Challa’s uniform in Black Panther—but the president of the French Tennis Federation reacted by banning such outfits in a new dress code, implying that the catsuit did not “respect the game and the place.” Like much of the most interesting clothes in the book, the suit had a logic of well-being behind it: it was like a full-body compression sleeve that relieved Williams’s circulation problems. Clothes, as she sees them, help an athlete compete at the highest level. But in addition to a superhero, we might see a woman in a garment that looks none too different from what the average American wears day to day, living life in pursuit of comfort and ease above all else. Think of how the late Virgil Abloh once designed a “West Village”–themed collection inspired by the woman who did SoulCycle on workdays and pursued equestrianism on the weekend. It was filled with crop tops, hot pants, leggings, and sneakers. The concept of athleisure seems less like surrender than the prioritization of a life of constant movement, or what is more commonly called the #hustle.

Rachel Tashjian is the fashion news director for Harper’s Bazaar.