BEYOND AN OLDER SIBLING’S headphones wringing the sweet, distorted fuzz of the Velvet Underground out and into my ears, my second most notable encounter with Lou Reed was in the pages of the Lester Bangs anthology Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, which has a whole section dedicated to Bangs and his relentless sparring with Reed. A book within a book, almost. There are two interviews that would, today, seem alarming in both their approach and the nature of their candidness, with Bangs demeaning Reed’s pal David Bowie, Reed taking the bait, Bangs shouting that Reed is full of shit. The interviews go on like this, Bangs and Reed clashing, arguing loudly, or with an on-page ferocity that occasionally veered into affection. Reed clamors on about the drugs he consumes to survive, Bangs takes Reed to task for his songwriting’s increasing laziness. Ultimately, in the essays Bangs wrote about Reed, without Reed in the room, we find that these clashes, brutal and invasive as they might have seemed in the interview form, were born out of a writer being present with a subject he admired deeply, growing frustrated that the mythology he’d made of the subject wasn’t being manifested in the person he had been so fascinated by. This frustration inspired some terribly cruel writing that eventually led to a permanent falling-out between the two.

Herein lies the problem of mythology. All mythologies, of course, but for the sake of this moment, it is the mythologies of musicians that I find myself most concerned with. Lou Reed is certainly not alone in this dilemma, nor is he the original architect of it. Reed, though, lived at an intersection of colliding affections and nostalgias that has made even the most trenchant attempts at critique difficult to wade through. For all of Bangs’s shouting at his idol, Reed was still his idol, clear to any reader. Bangs wasn’t interested in removing Reed from the pedestal as much as he was interested in—willingly or unwillingly—building it higher. Testing the structural integrity of it, amid the flaws of the person at the top.

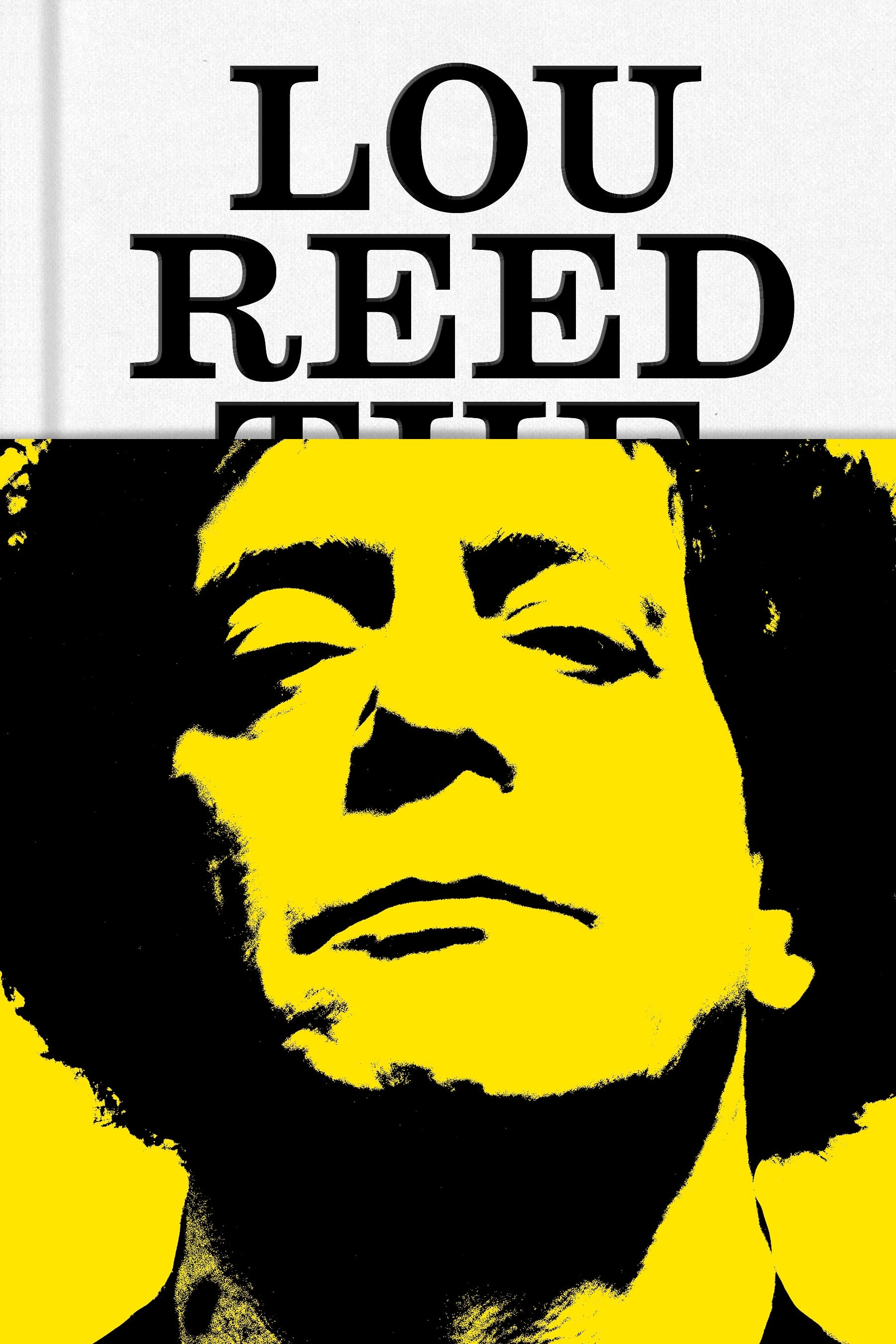

The achievement of Will Hermes’s book King of New York is, first, in how thoughtfully it contains Reed. It affixes Reed to his central muse: New York City. And, in doing so, it considers Reed through a very specific frame. One that is not entirely inflexible, but one that is a bit more confined, and keeps Reed’s elusive pull anchored in a concrete understanding of the geographic container(s) in which he operated. In the preface, Hermes addresses both the scope of Reed’s work and the scope of Reed’s mythology. One of the first lines in the book shows an awareness of the stories and exaggerations that “have been accepted as fact, some of them advanced by Reed himself, which didn’t help matters.” And so, from the start, we understand that Hermes knows he’s assessing the life and history of both a person and a performer.

Hermes refers to Lou Reed as someone who became a “character,” which initially felt a little harsh to me. But one function of a biography, I think, is to decide on a central idea and then follow through with a showing of the work, an in-depth mining of personal history. And so the labor of this book, in part, seems to be to parse the thought of when or where one shifts from performer to character, if there is a shift at all. If you, for example, step into a persona, perform that persona and then step out of it, put it on a shelf until the next time the spotlight calls, you are a performer. But then maybe you don’t step out one time, and then another, and then, before you know it, the performance becomes easier to stay in, and you are in it longer, and then it consumes you to the point of it becoming your life, and when you are performing a full life, I suppose that means you have become a character.

King of New York finds its trajectory by following a chronological and geography-based time line, beginning with Brooklyn/Long Island/The Bronx in the 1940s and ’50s and ending in West Village/Long Island in the 2000s. Much like Reed in his songwriting, Hermes is exceptional at filling his narrative with a robust population of characters. It is perhaps cliché at this point to discuss the City as Character, but Hermes accomplishes just that, going beyond simply naming streets and neighborhoods and giving them a distinct personality and life-force. In terms of introducing the people who were around Reed, Hermes at times moves at a breakneck pace. In the book’s second movement, we find Reed in upstate New York, in the early days of college, and meet future Reed bandmate Sterling Morrison, Reed’s neighborhood friend Art Littmann, and his college friend David Weisman. Reed’s affection for J. D. Salinger sends us on a brief Salinger detour. While it could be thought that we spend a touch too much time in the minutiae of Reed’s college life, the earliest chapters of the book operate in a way that earns itself out as the book progresses, funneling in a wide, seemingly overwhelming cast of people and influences who both inform and orbit the growing of Reed’s world—a world that, somewhat painfully, begins to shrink as the book progresses. That shrinking is beautifully rendered and paced by the writing of Hermes, but it is hard to watch, nonetheless.

If you are a reader who is coming to this volume to read about the exploits of the Velvet Underground, from its first rehearsals in 1964 through Reed’s departure in 1970, you’ll be satisfied. There’s enough familiar stories and anecdotes to keep any VU obsessive excited to stick around. But the heart of the book, where it began to really turn for me, is the book’s eighth act: Upper East Side/West Village, 1974–79. Candy Darling, an actress who was one of Reed’s many New York muses, dies at twenty-nine of lymphoma. Reed’s drug use accelerates, and he begins to fold into an imagined version of himself. He becomes distant from the actual self and starts to become a quilt of personae, stitched together from his various muses, the consistent hum of images and interactions that propelled Velvet Underground songs. One way he does this, as Hermes points out, is by manipulating his image. He became a thinning shell of his former self. His appearance became a playground for shock, an extension of some of the ideas that permeated his work. In this chapter, too, Hermes does spend a bit of time touching on the Lester Bangs/Lou Reed interviews, declaring 1975’s infamous “Let Us Now Praise Famous Death Dwarves” to be “one of the most spectacularly twisted pieces of arts journalism ever published,” and correctly pointing out one specific cruelty within: Lester Bangs’s horrific description of Reed’s muse and companion, Rachel Humphreys, who was a trans woman, as a “creature.”

I crave a delightful, in-the-weeds, deep-in-process narration about albums, and I am curious about sound and production and how something comes to life from an idea. And there is enough of that, in King of New York, to keep me present. Those who are looking for a massive deconstruction of Reed’s impulses or ideas when making, say, his notoriously alienating 1975 record Metal Machine Music, aren’t going to find too much of that. But Hermes cops to this work’s difficulties, and notes that Reed’s motivations were often scattered, sometimes hard to adequately grasp, and sometimes even harder to capture when Reed himself was the one attempting to explain them.

The book sits best with me when I consider it as an examination of obsession. To pursue a book of this heft, focused on a single subject and on that subject’s geographies, requires a type of labor that can only be defined by obsession. Hermes succeeds, I think, in treading the difficult line between obsession and a relentless type of fandom that might obscure the realities of a subject. Writers in pursuit of a single life might (as I have done before) find themselves slipping into being in awe of the spectacle of the life. Or writers might find themselves consumed by the seeking out of small and precious bits that expand and extend our rabbit holes of obsession, whether or not that seeking offers anything revelatory. Hermes figures out how to play with this a bit, in part because he seems to be operating with an awareness that Reed himself, his life, his mythology, has already been a point of consumption and obsession by many, who have, in their consumption, sometimes allowed affection to overwhelm the critical lens. This isn’t to say that fandom cannot be critical and that obsession cannot be affectionate, but from a writer’s perspective (and, I think, from a reader’s perspective), obsession is a sensitive bit of machinery, with many moving parts. It can be what brings one to the creating of a biography, but it cannot be the sole sound humming throughout the text.

The 1974–79 section acts as a sort of volta. Reed rises to a level of spectacle, and therefore his life becomes a spectacle, and therefore the people he loves and cares greatly for also become spectacle. Writers like Bangs and Peter Laughner approach Reed like many other people in many corners of the world would: led by obsession, one that made Reed’s work less about the work and more about Reed himself. The achievement of King of New York is in how it captures the growing isolation of a person being subjected to that degree of obsession, and how that shrinks a world, and shrinks the population of a story, of a life.

Reed’s life, as presented by Hermes, finds its tenderness in the book’s final two acts. The Upper West Side and West Village years of the ’90s and the West Village and Long Island of the 2000s. It isn’t that Reed is softened, or rendered without complication, but of the several lives Lou Reed lived, this is the one most teeming with scenery of touchable calm. Reed sharing his days with Laurie Anderson, walking his dog on a New York street. Affectionately singing alongside David Bowie. Reed turning away from music and toward photography and martial arts. Yes, the Metallica album. And, ultimately, Reed coming to terms with his own death. The final section of the book, the West Village and Long Island section, does move through a lot, very quickly, to a point where the book’s pace begins to tumble a tiny bit (requiring small moments of backtracking to get years and dates and places in order before jumping, rapidly, to the next scene). But there’s a tangible and heartbreaking period of slowing, when Reed, in the months before his death, begins to consider his own legacy. Telling his sister, “I don’t want to be erased.”

“In the end, not even Lou Reed wanted to die in New York City,” Hermes writes in the book’s final pages. He died on Long Island, sitting in the light breaking over his porch. It is a lovingly presented bit of closure to a book that is affixed to one person’s relationship to a place, and commitment to a place, even as that place transforms and, through its transformation, begins to disagree with the person who loved an older version of it.

The achievement of King of New York is also tied to that idea, in a way. There is an easy path to a type of Reed biography that prioritizes uncritical nostalgia. There is no doubt that Will Hermes is a fan of Reed, or at least someone invested enough in Reed to pursue a five-hundred-plus-page book about the artist. And yet through Hermes’s lens, Reed is complicated, flawed, and sometimes brutal—and not always forgiven for those flaws and brutalities. It is a work of grand affection, one that allows a person their failings, and one that knows that examining those failings alongside the grandest achievements is how one pays homage to a full life. It’s a removal of the pedestal, with care for the person atop it—who maybe didn’t ask to be there in the first place.

Hanif Abdurraqib is the author of There’s Always This Year, coming in March 2024.