IN THE AWARDS-SWEEPING 2021 documentary Summer of Soul, a man named Darryl Lewis recalls his first Sly and the Family Stone encounter, at the Harlem Cultural Festival of 1969. In those days, he says, “When you saw a Black group, what you expected to see was, generally speaking, all men, all dressed in matching suits, ready even before they hit the stage to perform.” But here, Sly and company “kind of saunter out,” men and women, Black and white, a living quilt of psychedelic patterns, knit caps, and sundry frippery. “The instruments weren’t tuned,” Lewis says. “You wonder, What are they doing with girls in the group? Why are there white people up there?” Once they began to play, though, the music’s ecstatic elevations dispersed all his friends’ misgivings. “My group of four guys, we were suit-and-tie guys. Then we saw Sly—we were no longer suit-and-tie guys! The change was in effect.”

A half century later, it’s difficult to take in just how much change the Family Stone effected, with Sly Stone as songwriter, arranger, producer, co–lead vocalist, and multi-instrumentalist. Yes, the group was mixed in race and gender when that was still near-taboo, some players being Stone’s siblings (it really was “A Family Affair”) and others poached from the best of the Bay Area scene. But those weren’t the only conventions they strolled past as if they’d barely noticed. They steamrolled over the binary of the respectability codes that governed northerly Motown versus the southern-bluesman grit fetishized by white-boy guitar wankers and record collectors. James Brown may have invented funk, but Sly Stone funked that invention and flew it over the rainbow. Each artist (Stone first) had a track called “Sex Machine,” but where the erotic engine of Brown’s martinet assembly ran on muscle, pride, and kerosene, the Family Stone’s movable feast was juiced up on peacock shimmer and cosmic candy. “It was fashion but it was also feeling,” as Stone puts it in the improbable volume that is his new memoir. “We could be who we were.”

The group’s legend-clinching moment came when it stole the show with “I Want to Take You Higher” at Woodstock 1969, despite being pushed back to 3:30 am in a rainstorm—“I hadn’t thought of it as a competition,” writes Stone, “until the results started to come in.” Then and there, the Family Stone, alongside Jimi Hendrix, briefly threatened to reclaim rock counterculture as Black culture, and to catch the world in a love embrace with all the imaginative impunity taken for granted by their Californian white hippie peers. (Stone had produced records for the Grateful Dead when they were still called the Warlocks, as well as the original version of “Somebody to Love” for Grace Slick’s pre–Jefferson Airplane group, the Great Society.) In the process, Stone invested his music with a racial and sociopolitical forthrightness not unprecedented but still unusual for Black pop that was aimed at radios and dance floors, rather than sit-ins and marches. Where Sly’s pipes led, the Temptations, War, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, and others soon would follow, riding a wave of socially conscious psychedelic soul.

Like many things about that era, it couldn’t last, and didn’t, even more cataclysmically than most. But the ripples thrown by the Family Stone would eddy out through decades of funk (Parliament-Funkadelic were disciples), jazz fusion (Miles Davis was a fan), disco, new wave, electro, pop (Prince crossed all these categories), house/EDM, and, by way of rampant sampling, hip-hop (which Stone says he welcomed). Since the early 1970s, each strain of Black boho creativity has had a tincture of Sly in it, and some of the white versions, too.

Even as his influence spread, however, Stone himself receded further and further from view. The Family Stone became renowned for arriving late to gigs and then leaving the stage early, or missing shows altogether, leaving outraged audiences in their wake. It only got worse after the band gradually broke apart. Stone flaked out on record contracts, got hauled in on drug charges, and flitted in and out of rehab. Reporters would track him down every few years and find him in precarious living conditions and alarming company. New music was always supposedly underway, and always going up in smoke, the kind from a crack pipe. His scant releases since the early ’80s have been one-offs, cameos on other artists’ records, or works clearly cobbled together by other hands. Stone repeats the condescending jibes: “Arrest records were my new records and I was hitting the charts. Court dates were my new concerts, and I was still just as good about arriving on time.” But the truth wasn’t very funny. Fans long ago stopped expecting to hear anything substantial from Sly Stone ever again.

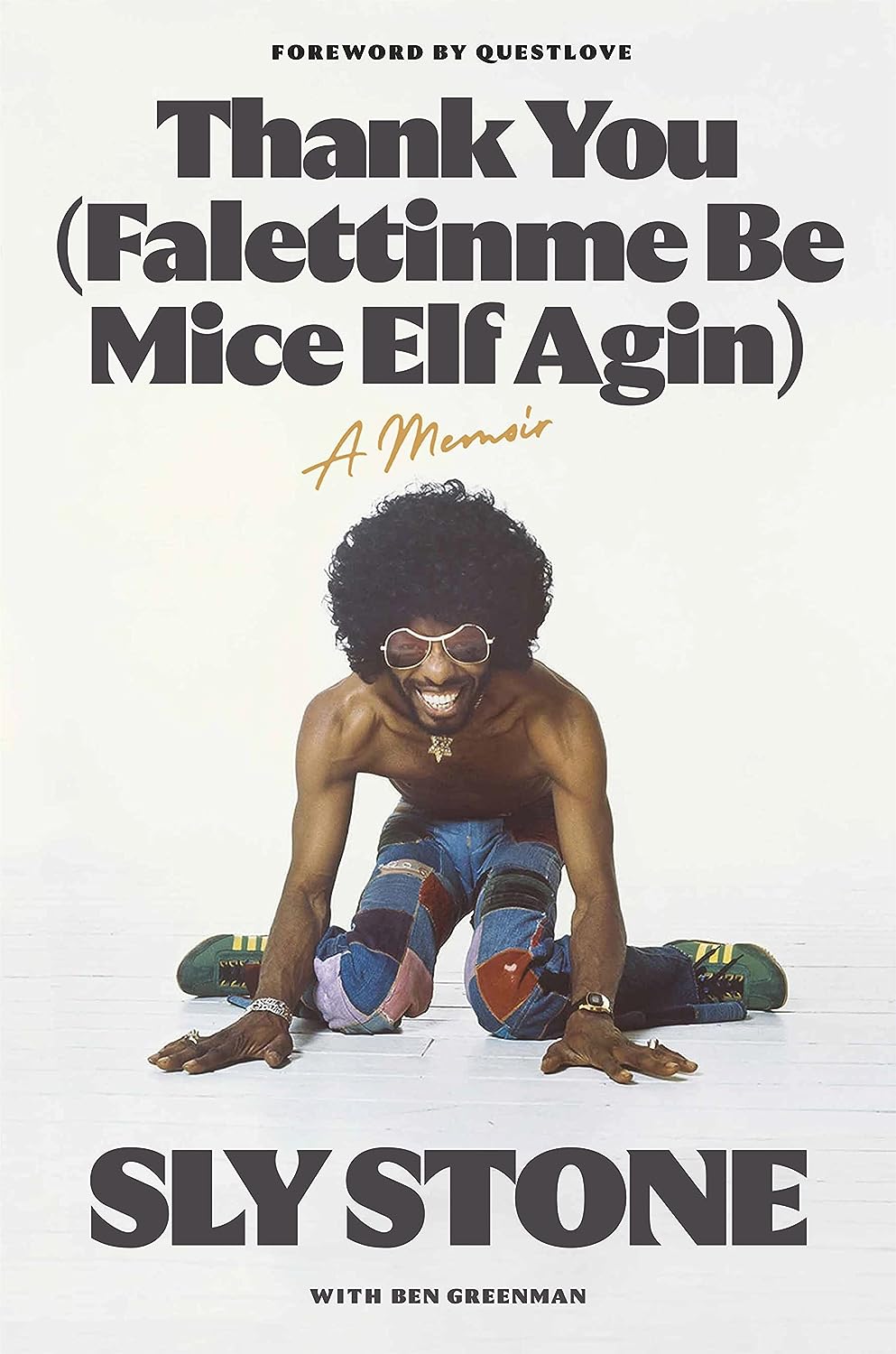

Then, this past spring, Farrar, Straus and Giroux suddenly announced that the first book out from its new imprint AUWA Books would be this memoir, titled Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Again) after one of the Family Stone’s most innovative hits. Stranger still, this fall, it actually materialized. Perhaps the only person who could have made it happen is the head of this new AUWA venture, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. Questlove is, of course, the drummer for hip-hop group the Roots, a producer, and a DJ, but lately he’s become America’s unofficial chief archivist and interpreter of Black popular music, via multiple books, websites, TV series, and podcasts, and by directing the aforementioned Summer of Soul, plus no doubt other initiatives I’ve missed. It’s a hell of an irony that his first publishing project would be the autobiography of a man who’s become one of the world’s most notoriously unproductive people. It’s a book remarkable for its very existence, if not always for what’s in it.

The book is cowritten by Ben Greenman, a novelist who’s also collaborated with Questlove, the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, Kiss’s Gene Simmons, and Stone’s frequent drug buddy, P-Funk’s George Clinton. What it must really have been like for Greenman to drag this document out of his subject comes across in the “Prelude” and “Postlude,” each a short dialogue with Stone: When Greenman suggests about his questions, “We don’t have to do them all,” Stone comes back, “We don’t have to do them at all.” At the end, Greenman asks what Stone might want people to take away from his life: “To take something from me?” the eighty-year-old musician asks, in a paranoid tone all too familiar to the reader by then.

The prose only rarely conveys a recognizably personal voice, usually when Stone gets going on music and outlining the ideas behind specific songs or albums, or in flashes of sentiment over lost family and friends. He’s given to reeling off bits of wordplay in the style of his lyrics, whether long-repeated aphorisms or spontaneous creations, usually to sidestep any deeper reflection. On first getting into harder drugs when the band spent a season in New York, for instance: “I was trying to write, trying to play, trying to record. All of that needed to be fueled. But how did that fuel make me feel? A drug is a substance, so the question has substance. A drug can be a temporary escape, so I will temporarily escape that question.” Elsewise there’s a lot of perfunctory then-we-did-this-and-then-we-did-that, with Greenman drawing on external sources to fill in the blanks. Pages at a time recap past magazine profiles or TV appearances, marginally freshened up with present-day reactions. I don’t fault Greenman for using whatever prompts he needed to jog his collaborator’s addled recollection. Too bad they don’t produce more insights or reconsiderations.

But the primary undertext to which Greenman and Stone are responding, though never explicitly mentioned, is Joel Selvin’s 1998 book, Sly & the Family Stone: An Oral History, last updated and reissued in 2022. Selvin talked to dozens of participants and witnesses from the band’s origins through its final fracture circa 1974–75—nearly everyone but Stone, who does not come off well. The richest way to approach Thank You is as Stone’s missing counterpoint to the Oral History, reading Selvin’s accounts of a period first, then Stone’s. He might concede or contest his associates’ accusations (from the extent of his no-show lapses to graver matters like abuse of his romantic partners), or else throw up his hands: “What can I say to all of that?” the old man declares, struggling not to reignite grievances over what’s been said. “It’s the name of the game, but it’s a shame all the same.” Past the era Selvin’s book covers, I felt the loss of that chorus of voices; it’s a grimly realistic simulation of Stone’s growing isolation in his own self-destructive orbit.

The contrast could hardly be greater with the warm, boundlessly energetic kid we meet in Part One of Thank You, which ranges from the 1943 birth of then-Sylvester Stewart through to the Family Stone’s annus mirabilis of 1969. He was the second child and eldest boy of K. C. and Alpha Stewart of Denton, Texas, who soon moved to the booming port town of Vallejo, California, about thirty miles northeast of San Francisco. Outliers to the standard northward pattern of the Great Migration, these newfound Californians arrived in a society less settled and fixed in its ways than most of the nation. Later, when their kids started up a band, you might say that—not entirely unlike the British Invasion a few years before—their geocultural distance from the birthplaces of rock ’n’ roll and R & B let them translate the sound back to America at large in a new dialect, so it could be heard afresh.

Family life revolved around the Pentecostal Church of God in Christ, and the Family Stone’s polymorphous musical style may spring partly from their oral traditions of testifying and speaking in tongues, unlike the more orderly gospel of Baptists and others. The Stewarts were musically active, a de facto family band. “When I went out into the world,” Stone writes, “I was surprised to see people who weren’t carrying instruments. I wasn’t sure what they did instead.” And young Sylvester was often spotlighted: in 1952, the four youngest siblings put out a single as the Stewart Four, with him singing lead on two hymns, before he was even ten.

Vallejo was highly multicultural: white supremacy still reigned, but perhaps less heavily than average for the time. Forecasting Stone’s future, his first secular band, the Viscaynes, was somewhat racially integrated, stemming from his high school’s “Youth Problems Committee.” (They also put out a couple of well-received records.) He dropped out, but found his way to a community college for music-theory lessons that would be invaluable for his later arranging and composing. When he quit again to move to the big city, he promised his mentor there that he’d return in a limousine.

Stone quickly became the most popular evening DJ on a San Francisco R & B/soul station. There he modeled his quick-fire patter on hipster spoken-word artist Lord Buckley (in effect appropriating Black jive style back from a white appropriator), and transitioned from Sylvester Stewart to Sly Stone: “Sly was strategic, slick. Stone was solid.” When the Beatles and Bob Dylan broke, a smitten Stone challenged segregated programming by playing them alongside Jackie Wilson, Sam Cooke, and Ray Charles. He kept up the DJ gig for a long while even after he got the band together. His station connections soon led to record producing as well, including hits by Bobby Freeman (“C’mon and Swim”) and the Beau Brummels (“Just a Little”). With all his musical activity in different media, the young Stone seems almost like a mid-’60s Questlove.

His ambition and performative extroversion helped the Family’s cult following swell, first in the suburban clubs of the Bay Area, and eventually to national breakthroughs with “Dance to the Music” and “Everyday People.” Serious trouble didn’t come till they peaked commercially and relocated from San Francisco’s peaceable kingdom to New York and then to Los Angeles. In classic early-’70s fashion, only worse, Stone’s LA mansions became perpetual parties overrun with hangers-on, guns, copious pills and powders (he’s said to have been at his worst on angel dust), vicious dogs, and you name it. As he writes at one point, “Manson had his family, and I had mine.”

But it’s clear from Selvin’s book that Stone was at heart too sensitive to handle such a scene, even as he insecurely put up a front for the toughs and gangsters he was drawn to as bodyguards, boosters, and perhaps father figures (though his actual father was living and touring with him all the while, a dynamic that’s never been satisfyingly clarified and certainly isn’t here). People seemed to desire at once to protect Stone and to exploit him, and their vying for influence escalated into division and violence. His own immaturity, appetites, and volatility did the rest. It’s impressive amid that level of excess that he went on generating great music for the few further years that he did. But he probably was only truly comfortable when creating, in the studios he built in his upstairs bedroom and outside in a Winnebago.

Those were the main places he assembled the 1971 anti-masterpiece, There’s a Riot Goin’ On, which in aficionados’ and critics’ canons has come somewhat to overshadow and arguably distort the Family Stone’s legacy. It’s no question an early and influential artistic milestone of post-’60s, post–civil rights movement, Nixon-era disillusionment. But there’s an intellectually macho critical tendency to treat artists’ darker, more initially misunderstood work as their most meaningful, as if it would be too obvious to celebrate their attractive and popular ones. I hardly ever hear people talk about 1969’s Stand!, the group’s most fully realized statement of purpose, expansive and enveloping but still frank and nervy. Or even 1973’s Fresh, a commercial backtrack created with ever-fewer original Family members, but still a highly listenable record—and the one I most often saw in people’s houses growing up, with its iconic Richard Avedon leaping-Sly cover photo.

Some of the response to There’s a Riot Goin’ On comes from an overly literal reading of its title. It was conceived as an answer to Marvin Gaye’s What’s Goin’ On?, but the riot Stone had in mind was as much within himself and other people as in the nation. On urban uprising itself, he tried to put across his own not-so-fashionable viewpoint by making the title track exactly zero seconds long, to imply, he writes, “Don’t give any time for violence.” It was his version of John Lennon on “Revolution” singing, “But when you talk about destruction / Don’t you know that you can count me out.” Riot is the most thoroughly utopian ’60s band’s response to the deflation of its hopes, but it’s not a dystopian fantasia. In the course of Stone’s book, although he isn’t always well-informed on the facts, his response to political unrest—the LA riots, events post-9/11, even the George Floyd protests—is always the same: “Why did people feel such excitement at the idea that we weren’t all on the same side? I was never going to be at peace with that.”

I suspect some interpretations of the music have been swayed by tales of Stone’s early ’70s lifestyle. In Greil Marcus’s landmark 1975 book Mystery Train, Stone is treated as an avatar of the “Staggerlee” archetype, that of the murderous Black outlaw who rejects the morality of a sick society and thereby sets himself free. There’s a Riot Goin’ On is positioned in relation to the decline of the Black Panthers and the rise of Blaxploitation movie protagonists like Superfly (plus their excellent funk soundtracks). I’m a huge admirer of Marcus’s criticism, but I think he goes astray here: That’s not Sly Stone the artist, and probably not the person, either. He wasn’t an outlaw individualist but a community idealist, the kid from the Youth Problems Committee—Marcus never mentions that the Oakland Panthers actually disliked and by some accounts even threatened Stone because he worked with whites and wouldn’t endorse their version of Black Power.

Stone may have liked feeling tough by association with the likes of small-time pimp Hamp “Bubba” Banks, a friend he made in his DJ days who lingered too long. But he fell in so deep with the underground mostly because that’s where he could get the drugs, the muscle to shield him from the consequences of his own mistakes, and companionship when everyone else had been pushed away. But he was far too insecure in his swagger to be a Staggerlee—pimps and dealers can claim that role, but not junkies. (In the more recent mythos of The Wire, Staggerlee could be Avon Barksdale or Omar Little, but he’s certainly not Bubbles.) If you’re looking for the Staggerlee in Stone’s memoir, you won’t find him in the narrator—it’s when Ike Turner briefly appears among Stone’s lowlife circles in the ’80s, and the reader feels the whole atmosphere suddenly shudder with dread.

In fact, the young Stone, on the hustle 24-7 for his cause, reminds me more of a countercultural version of Death of a Salesman’s Willy Loman, putting everything he’s got behind an American promise that should but never would come true. You need only listen to the Family Stone to believe it, fleetingly, too. The poet and essayist Richard Deming’s new book This Exquisite Loneliness quotes Arthur Miller on the point of his play: “We are trying to save ourselves separately, and that is immoral, that is the corrosive among us.” Which is very near how Stone paraphrases his own music’s prime directive: “Everyone had to be free all the time or no one was free at all.” The tragedy of Sly Stone is sharpest in that gap between the liberated togetherness his music summoned and the trapped aloneness that addiction brings. This book has the wherewithal to document that process, but not to illuminate it.

That project may have to be left again to Questlove, who says in his foreword that he’s at work on a new film that will use Stone as a prism for questions about how “Black stars have a particularly rough road in America, full of unimaginable pressures, internalized trauma, and survivor’s guilt.” For all his personal transgressions, Sly Stone surely also endured America’s punishment for the crime of Hoping While Black, which carried him to depths directly proportional to how high he once yearned to take us.

Carl Wilson is Slate’s music critic and the author of Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste (Bloomsbury, 2014).