SOMETIMES WHAT CONSERVATIVES SEEM TO FEAR MOST from liberals is not their money or their ideology but their judgment. Beneath the vast tide of right-wing grievance, there is a current of profound insecurity, a suspicion that liberals don’t think conservatives are good enough. There is nothing they desire more than the sight of a liberal humbled into seeing the light. To cater to this desire, the media has produced a peculiar new kind of pundit: the conservative who pretends to be a liberal—one agreeing, in spite of themselves, with the conservatives.

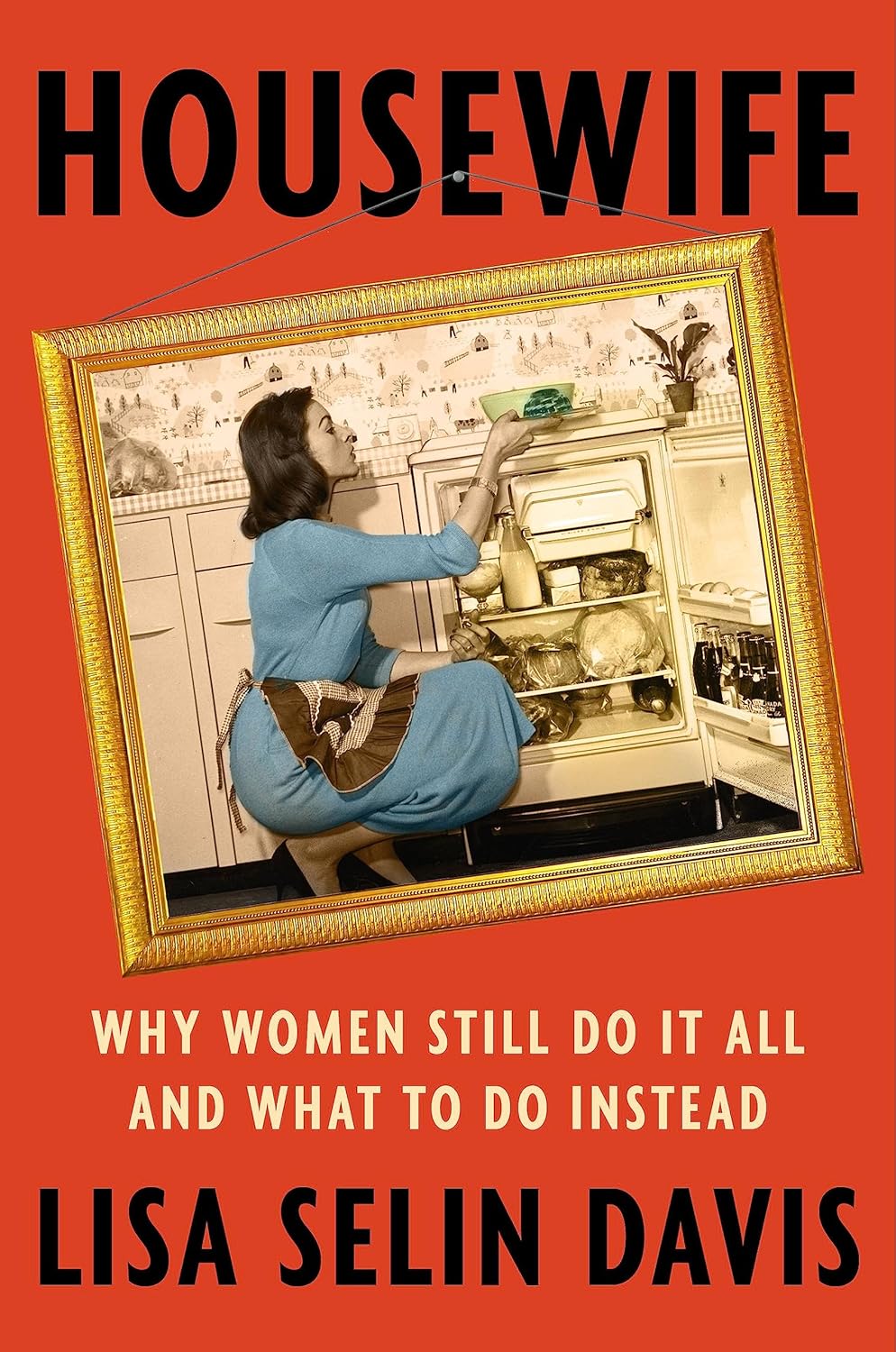

You will best understand Housewife: Why Women Still Do It All and What to Do Instead, Lisa Selin Davis’s new nonfiction book about women’s role in the family home, if you see it as a response to this demand. In the book, Davis poses as a liberal coastal feminist. She says she studied “experimental feminist video” in college; naturally, she lives in Brooklyn. Davis summons an image of a comfortable yuppie life, surrounded by other well-off millennial mothers: a scene heavy on clogs, yoga, and latte art. Her actual friends turn out to be less easily typecast figures: the one she appears closest with is a professional “libertarian” magazine editor. But it’s the impression that counts.

These liberal bona fides are supposed to lend authority to Davis’s assessment of women’s work and ambition. But her argument is at its core a socially conservative one: she thinks there’s nothing wrong with a return to traditional gender roles. To Davis, the burdens of working motherhood are impossible to manage, and housewifery has not so much been discredited as placed cruelly out of reach. The State must be marshaled so that women can drop out of public life and assume the unfairly maligned role of the housewife.

At least, this is what Davis seems to be aiming for. Housewife is a profoundly confused book, frequently contradictory and always intellectually undercooked. It would be generous to say that it has a thesis. At times, Davis’s sympathies appear plausibly feminist, like when she laments the end of World War II–era federal childcare programs for working mothers. At other times, her politics are straightforwardly reactionary, like when she waxes poetic about the aspirational lives of the “tradwife” influencers she follows on Instagram. But the book’s inconclusiveness seems more like the product of a rushed writing job than of a sincerely felt ambivalence. Davis doesn’t doubt that the housewife’s lifestyle is desirable; she merely regrets that it has been made inaccessible.

Of course, she’s only talking about a few housewives. Davis notes that the housewife has historically been an upper-class phenomenon and that this has changed; these days, the largest group of nonworking adult women is the immigrant poor. This would be an interesting shift to examine, but Davis doesn’t. Working-class women and women of color disappear into the background. Queer people, too, do not rise to relevance. When Davis mentions what she calls “LGB families,” she does little more than to note—with a straight woman’s typical defensiveness—that a lot of lesbians get divorced. A separate section, on trans women, makes only the weird claim that they don’t do chores. But these are little more than distractions: Davis focuses almost exclusively on white, heterosexual cis women of the middle class—and the effort to reconcile them to domesticity.

Housewife’s brand of anti-feminist feminism is by now an established genre of its own. Nonfiction books, usually padded with a hefty dose of memoir, appear every year on the lists of major publishing houses, written by white women who issue dispatches about their newfound, supposedly forbidden anti-feminist realizations: that work-life balance is hard, that children can be delightful, that they enjoy the company of their husbands. Sometimes these books are pitched at twentysomething women navigating heterosexual dating: Louise Perry’s The Case Against the Sexual Revolution is one recent item; Katie Roiphe’s The Morning After is a classic of the type. Other books, like Davis’s, seek to intercept these women a little later on in life—in their thirties or forties, as they struggle with marriage, motherhood, and working life. Housewife can be seen as a modern update to Caitlin Flanagan’s To Hell with All That: Loving and Loathing Our Inner Housewife, from 2006, which was itself a response to Lisa Belkin’s blockbuster 2003 New York Times Magazine piece, “The Opt-Out Revolution.”

Housewife at first seems to be situated squarely within this genre, with Davis following the well-worn narrative grooves of women who have gone before her, explaining in detail where feminism led them astray. Unsurprisingly, it was the birth of her first child that began her ideological conversion. “My compulsion to write vanished, replaced by this shimmery thing I vaguely recognized as happiness,” she breathlessly recounts. “My daughter had cured something in me: my ambition.” Later, the seed of an idea: “To be a housewife required a husband or a spouse willing to support a wife. I’d never been presented with that option. But, upon reflection, I might have liked to hitch my wagon to someone, confident that he or she loved me enough that I could be comfortable in a state of financial dependency.”

Feminism emerges in Davis’s account as the product of a deprived woundedness, something that happens to women in the absence of a secure attachment. Women’s drive for independence is cast not as self-respect, but as insecurity, compulsion, and unhappiness. This is a common sleight of hand in anti-feminist feminism, deployed like a party trick: dependence, it turns out, is the ultimate freedom.

DAVIS IS A NONCOMMITTAL THINKER. Her admiration for the housewife is like the nostalgia one might feel for a difficult dead relative: she wants the housewife back in her idealized form, even as she knows that’s not quite the form the housewife took. But if Davis is loyal to anything, it is the aggressively equivocal notion that women should pursue their own desires and shouldn’t have to ask whether those desires challenge or reaffirm the subordination of women. This approach is sometimes called “choice feminism.” By its logic, all choices—no matter their motivations or outcomes—must be judged the same.

Under this pretext of impartiality, Davis argues for the return of the housewife as a cultural fixture. She does not mean to force anyone to be a housewife. She simply wants women to have the choice to be one. This approach requires some elisions. “Davis builds a case for systemic, cultural, and personal change,” reads the jacket copy, “to encourage women to have the power to choose the best path for themselves.” To encourage women to have the power to choose—has there ever been a phrase so hostile to meaning?

The book itself is equally confusing. For one thing, Davis can’t quite decide what she means by “housewife.” Some of her “housewives” lived before the invention of the house. A chapter on “The Neolithic Housewife” examines the available evidence—not much—about the distant historical origins of the sexual division of labor. In this realm, Davis does what most pop-nonfiction writers talking about prehistory do: she concocts just-so speculative narratives to create historical justifications for her preferred ideology. For Davis, these cavewives show that the division of labor by sex is, if not natural, then at least morally neutral, divorced from any hierarchy of power. It is “not necessarily about which sex is superior, or about what women and men should do respectively,” Davis says, wondering about who would take care of the kids when early humans needed to go and hunt a woolly mammoth. “It’s really just about efficiency.” Efficiency: a virtue we are supposed to admire in cavemen. Pay no attention to power, Davis’s hand-waving account of prehistory seems to say. Pay attention, instead, to that glitteringly neutral ideal.

There is a brief sojourn into early America, in which Davis pays deference to the concept of “Republican motherhood.” “Mothers’ and housewives’ premier task was raising children to become proper American citizens,” Davis explains. “(Especially sons).”

But Housewife quickly progresses to twentieth-century America. This great jump through time conveniently allows Housewife to largely skip over the advent of capitalism and the Industrial Revolution. This might have proved more fertile ground: the definition of “housewife,” after all, relies on a stark divide between the home and the workplace that is historically quite recent: for most of human history, these were one and the same. It was only the advent of industrial capitalism that divided work from home—and, despite Davis’s forays into speculation about cavemen, it was only the Industrial Revolution that led to the Victorian idea of “separate spheres,” and the subsequent invention of the housewife. Davis misses an opportunity to seriously examine the work of women she calls “militant housewives,” like the African American activist Fannie B. Peck, who organized the National Housewives League in 1933 to encourage Black women to patronize Black-owned businesses—a pointed politicization of women’s consumer power. A serious historian might dwell on these connections between the ideology of gender and the needs of capital, and many have. Davis doesn’t.

Instead, Davis turns her attention to the mid-twentieth century and the much-demonized trend of medicating and lobotomizing housewives. “Why have housewives historically been one of America’s most heavily medicated demographics?” Davis asks. A decent question, but one that her allergy to analysis of gendered power makes impossible to answer. Instead, Davis’s noncommittal framework here reaches its most absurd form: a chapter so garbled that at times it reads like she’s trying to see the good side of lobotomies.

Lobotomies were popularized in the 1940s by the neurologist Walter Jackson Freeman II. Freeman’s patients were disproportionately women—about 75 percent—and many of them were housewives. The operations alleviated psychological distress by muting most adult psychic capacities. Lobotomized women were described as lethargic, patient, fond of ice cream, and very calm. Freeman called this state “surgically induced childhood.” Davis, paraphrasing the doctors, calls it “losing sparkle.” “63 percent improved—something people who remember lobotomies only as a medical scandal often forget,” she quips. Davis reports that Sallie Ellen Ionesco, a housewife who was lobotomized by Freeman, told NPR of the man who cut out a large portion of her brain, “He was just a great man. That’s all I can say.” These are the chapter’s last words and could be read as a moment of portentous irony. But it’s hard to tell. After all, the framing perfectly aligns with Davis’s logic of choice feminism: we must respect the desires and judgments of women whose very capacity for desire and judgment has been cut out.

FOR A BOOK with such an ambitious time line, it’s not clear that Housewife’s author has done much of the reading. There is no mention of the Italian feminist Silvia Federici, whose work on reproductive labor has been essential to theorizing the housewife’s relationship to capital. There’s only one brief mention of Arlie Russell Hochschild, whose seminal 1989 ethnography, The Second Shift, revolutionized understandings of marital inequality and the role of domestic labor in working women’s lives. Davis’s book can be understood as a twenty-first-century rebuttal to Betty Friedan’s 1963 anti-housewifery classic, The Feminine Mystique. But it’s not clear that Davis has read it. She recounts a famous scene in which Friedan writes about a boyfriend who dumped her for being too ambitious in her Berkeley graduate school days. “It was pointless for her to keep pursuing her studies and outshine him” is how Davis glosses Friedan’s account of the incident. “Reader, she married him.” Except that she didn’t. (The man Friedan ultimately married was not that Berkeley psychology student; he was, in fact, a children’s party clown.)

If the book is light on familiarity with feminist critiques of housewifery, it is also somewhat lacking in critical engagement with the housewife’s contemporary boosters. At one point, Davis takes to Reddit to understand modern online tradwives. She encounters a person who tells her that they are a housewife whose nonworking domestic lifestyle is part of a broader sexual arrangement of full-time, eroticized submission to a husband. “CrinkleCrackleCrunch” claims to be a mother to multiple “munchkins,” engaging in “Happy Cliché 1950s Housewife Play” as part of an arrangement of “Total Power Exchange (TPE).” “He’s my Master and I’m his slave,” CrinkleCrackleCrunch tells Davis. “He’s my owner and I’m his property.” Davis appears to believe, and expects her readers to believe, that this person is a real housewife, providing real insights into the lifestyle.

This is one of many moments when reality undermines Davis’s fantasy. In a chapter bemoaning the economic vulnerability of housewives, a woman tells Davis of how life as a homemaker ruined her financially. She married rich, had a slew of children, and dropped out of the workforce to homeschool them. When her husband left her, she was shocked to discover how few rights to support she had in divorce court. Now she had no income, no skills, and a brood of dependents. The woman’s anguish and fear are almost unbearable on the page—her betrayal, her regret, her desperate terror of the future. But Davis, ever the optimist, is determined to look straight past this reality and to fix her gaze on the bright side. If she hadn’t been a housewife, Davis reasons, this woman would not have been blessed with her children.

Housewife may be poorly researched and incoherently argued, but it is trying to address a real problem. Women’s domestic lives really are in disarray. The institution of the family home is in crisis—or, really, the women who are tasked with maintaining that family home are. The combination of work and domesticity is too much: working mothers are overburdened, exhausted, short on time, and thin on patience.

This issue is newly salient. When the pandemic shuttered schools and forced much of the white-collar labor force into remote work, the strains of 24-7 childcare, combined with the farce of remote schooling, the management of newly crowded households, the unrelenting demands of their jobs, and the confrontations with mortality that inevitably arose in an era of mass death, pushed many American women to a breaking point. Lots of them drank too much; others found themselves driven to desperate anger. In early 2021, the New York Times detailed the rising domestic cataclysm in the series “The Primal Scream: America’s Mothers Are in Crisis.” The University of Wisconsin, Madison, sociologist Jessica Calarco is following up this June with her book Holding It Together, an empirical study that supports her viral pandemic-era quip: “Other countries have safety nets. The US has women.” But perhaps what was most painful about this private strain was women’s sense that each of them was carrying it alone. They could not help but notice—as they changed diapers, wiped noses, attempted to sound professional on a work call as they gestured at a Zoom class with one hand and wiped applesauce from their shirts with the other—that their husbands weren’t doing very much at all. Or at least they were not doing half. The recognition of this reality has led to a crisis in marriage, particularly in the kind of middle-class marriages that people write books about, the ones that Davis finds most interesting.

Today, many middle-class women are finding that their marriages are incompatible with their dignity, and so they are leaving them. Everybody is getting divorced. Lyz Lenz’s pro-divorce polemic, This American Ex-Wife, was released on the same day in February as Leslie Jamison’s soul-searching divorce memoir, Splinters. This summer, they will be joined by the acerbic divorce novel Liars by Sarah Manguso. Meanwhile, defenses of marriage are springing up in a kind of preemptive backlash. New York magazine writer Emily Gould wrote a viral essay about her own decision to remain married, writing that a feminist politics of grievance had led her to a narcissistic disavowal of responsibility for her marital unhappiness. February also saw the publication of the latest dispatch from the anti-feminist University of Virginia professor Brad Wilcox, who offered the right-wing response to feminist critiques of marriage with his own book—titled, straightforwardly enough, Get Married.

But just because the problem of marriage is trendy does not mean that it is new. Feminists have been forced to confront this conundrum every decade or so since the Second Wave era. The issue is this: though women have made some strides toward equality in the public world, the private sphere remains strongly unequal.

Women still perform the majority of household chores, childcare and eldercare, the social maintenance that academics call “kin keeping,” (i.e., remembering their mother-in-law’s birthdays), scheduling, and the management of conflicts, resources, and outside help. Men today do slightly more of this than their fathers did; they do not do nearly as much as their wives do. Women’s domestic labor is relied upon and enjoyed by everyone in their families, but always goes uncompensated and routinely goes unnoticed. This inequality persists up and down the income ladder, taxing women’s time until they become rich enough to pay other women to do it for them. A woman can be high achieving, well earning, respected in her field, and educated up the wazoo. Or, if her career looks more like mine, she can be modestly achieving, poorly earning, tolerated in her field, and middlingly educated. It doesn’t matter. When those two women get home, they’re both still going to have to pick up someone else’s socks.

For years, this was the bargain that feminism struck with heterosexuality: give us our rights in the public sphere and we will not infringe upon men’s entitlements in the private one. It was never a tenable arrangement; the terms undermined each other. Being serviced and tended to by women at home made men less inclined to treat women with respect at work; achievement and independence at work made women less interested in performing subservient labor at home. But some feminists tried to keep up the lie that this could continue, in part out of a desire to avoid provoking men’s misogynist resentment. This, more or less, was Friedan’s position: that woman would assume equal status in the public sphere through work and education but remain compliant with the hierarchies within marriage that made her childlike, dependent, and subservient in the private sphere. Friedan, whose Feminine Mystique is credited with puncturing the myth of the housewife’s domestic happiness and ushering in the Second Wave of the feminist movement, was in fact quite frustrated with her own husband, Carl, and his unwillingness to fulfill his half of the domestic bargain: being the breadwinner. According to a recent biography of Friedan by Rachel Shteir, when their bills arrived at the end of the month, Betty used to hide her pocketbook.

But if this bargain of public equality paired with private subservience was always untenable, then recent decades have made matters worse. Paid work has become less remunerative and more demanding, as employee protections recede and new communications technologies render workers permanently available to their bosses. Parenting, too, has become more intensive, with standards for parental attention, investment, and involvement increasing. Friedan’s bargain, in which progress in the public realm would be paired with persistent responsibilities in the private one, was always hypocritical. Increasingly, it is also simply impossible.

WHAT KIND OF WOMAN FANTASIZES ABOUT BEING A HOUSEWIFE? Maybe just the kind who is overworked. The fantasy promises leisure, security, a life of gentleness and low stakes. When Davis tries to live as a tradwife, she imagines “taking over the cooking from my husband” and “cleaning way more than I normally would”: dutiful little projects that don’t matter very much. Men’s role in this fantasy seems hazy, and indeed, men are largely absent from Davis’s book. In her account, they are passive creatures, never implicated in women’s overburdening; it barely seems to occur to her that they might do more housework so that women might do a little less. But Davis does critique men’s failure to earn, and their steadfast refusal to play breadwinner so that women can play house. When Davis tells her husband that she is embarking on a weeklong stint as a tradwife, he seems confused—before realizing what this effort means for him. “Oh,” he says, his face falling. “I have to be the husband.”

There is nothing suspicious—or particularly gendered—about a desire to rest. But if we can sympathize in this respect with women who are drawn to the housewife fantasy, then we must also address the housewife’s immature side: her refusal of responsibility in the public sphere. The housewife lifestyle abandons the struggles of feminist advancement, community building, justice, and political engagement. It trades them for insularity, callowness, and superficial self-regard.

And here we return to Davis’s initial characterization of housewifery’s appeal: “I might have liked to hitch my wagon to someone, confident that he loved me enough that I could be comfortable in a state of financial dependency,” she writes. This desire to be taken care of, to be loved in a way that obviates responsibility, is not a fantasy of a marriage. It is a fantasy of a return to childhood. She’s not looking for a husband; she’s looking for a parent.

Moira Donegan is a writer and feminist.