POET AND LITERARY CRITIC Jamie Hood’s Trauma Plot: A Life is a destabilizing achievement of radical self-exposure, interrogation of form, and defiance of reader expectation. Setting out to capture what it’s like to live through sexual violence and its aftershocks, the memoir records all the pain, the horror, the numbness; the forgetting and remembering and haunting; the loathing, anger, shame, abjection; the dissociation, the reenactments, the substance abuse, the revictimization. Hood dives into the wreck, circles the drowned evidence of damage, and barely surfaces for air.

Spanning some thirteen years and structured by three rapes Hood endured, the narrative is divided into four sections, each composed in a different style, employing a different pronoun (she, I, you, we). Culling diaries and therapy transcripts as well as newspapers and reported books, Hood revivifies her splintered selves to mimic trauma’s effects. In this way, she becomes at once a series of presenting patients and the sole femme médecin at the old Salpêtrière Hospital. She performs a relentless, fiery demonstration for all of us—from misogynists and revanchist literary critics to “girls who haven’t given grief their language”—to witness sexual violence’s devastation of the mind and body. But Hood isn’t diagnostic, and no one is getting committed. This isn’t a display for paternalistic study. Rather it’s a record of life as lived by a woman in twenty-first-century America. It’s also the stuff of literature. Yet Hood will not cut her conscience to fit this year’s literary fashions: she will not cauterize her wounds or offer up a tale of redemption. In her rage against the machine that allows, even promotes, raping with near impunity—at higher rates for trans women and women of color—that slickly deploys the ideal of the perfect victim to discredit everyone, and only tolerates tidy stories of hurt and healing, Hood in essencechants and then shouts, Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me!

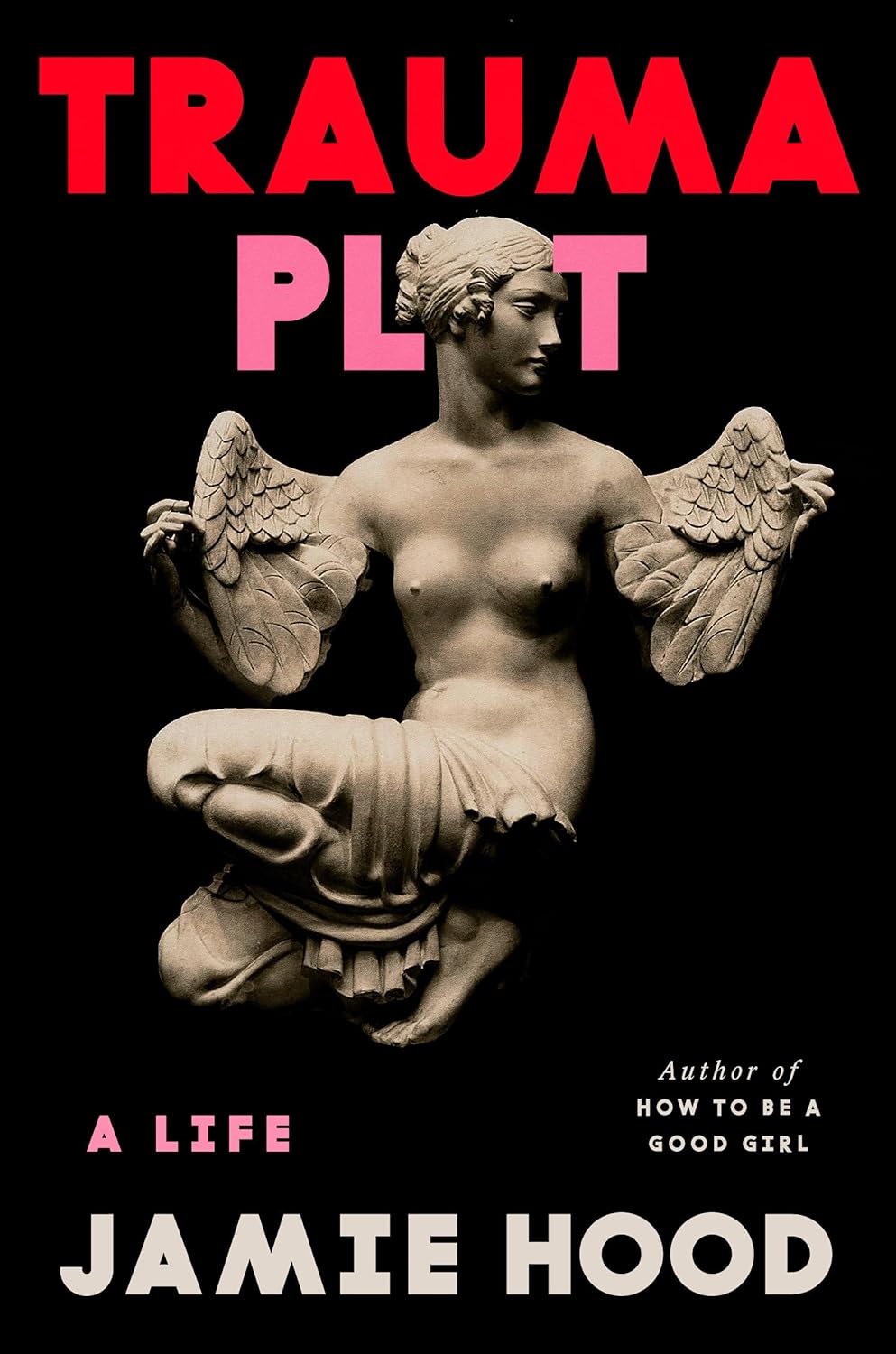

In recent years, Hood has emerged as a formidable critic writing about the likes of Rachel Cusk, Annie Ernaux, Kate Zambreno, and Virginie Despentes, as well as the political-social backlash against #MeToo, for magazines like this one, The Baffler, The Nation, and The Drift. She is also the author of the poetry collection How to Be a Good Girl—first published by Grieveland in 2020, now reissued by Pantheon—in which she wrote, “once a semi-stranger told me i could be v marketable! quite successful! if I were to continue this public flaying of my self instead on the basis of my so-disputed sex / that is; wrote of my transness as tragic; the failure of having been born cis / —rather than to take as my writerly preoccupation the architectural & affective / bizarrities of desire . . . / shelters sought in the wake of trauma . . . / i said thank you & ordered another shot.” While Hood originally intended Trauma Plot to contain poetry, she decided against it, and it is her critic’s voice we hear first in this book, an introduction that triples as a political statement, literary polemic, and prolegomenon.

Hood situates her near-decade composition of Trauma Plot across the breaking wave of #MeToo: the ripples gathering from the Access Hollywood tape and Trump’s election in 2016, to the massive swell crashing on the culture from October 2017 to July 2018 (Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation), to the swash sinking into the sand, and a backwash so forceful by 2021 it was hard to see any damage to the structures of power standing on the shore. She locates a representative moment of the ongoing retrenchment in the discourse around Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life and Parul Seghal’s much-discussed essay “The Case Against the Trauma Plot.” For Hood, Seghal and other critics of trauma-plotted tales, which they complain flatten character and narrow literature’s bounds, “use an old trick, the same used to argue autobiography is antithetical to art; that confessional writing is without tradition; that it’s hack, just bloodletting on the helpless, virginal page.” In a defense of A Little Life that sets up Hood’s own project,she says that “it was one of the only novels I’d read that saw how pervasive intimate violence is in our lives, and how shadowy, how stigmatized, how great the pressure to stay stoic in facing it, to weather violence without complaint.” This segues into a guide for interpreting Hood’s book: “I’ll always jump into the ring for the earnest, the cringe, the sentimental, the too much. I write for the messy bitches.” Quoting Annie Dillard’s metaphor of writing and revising as home construction, Hood instead insists: “What I needed was to sit among my rubble and weep. I allowed chaos, and not its tidying, to be the book. None of the usual walls or fixtures sufficed.”

In florid, flowing third-person prose, an homage to Mrs. Dalloway, Part I is set over the course of one day in Boston in 2012. While Jamie H. struggles with her dissertation on Sylvia Plath and prepares to host a party that evening, she is haunted by the “inscrutable watchfulness” of what she calls “the Specter.” Eventually, the Specter materializes as the ghost of her brutal rape by “the Diplomat” six months prior. We enter the first person in Part II, which centers on Hood’s second rape, in February 2013, around the topsy-turvy time of the Boston Marathon Bombing. Having been drugged the night before, Hood comes to dead-limbed consciousness beneath a man in a gray room, although my description is only literal: “If there was a room, I wasn’t in it. If a body was being fucked there, it was the meat sheath of some other luckless bitch.” Carefully drawn and quoting from “an exhaustive daily diary,” Part III takes up the second person in the present tense in New York City in August 2013. Hood reads a lot, tends bar, starts doing sex work, and dates lousy guys. (“On the twenty-eighth you go home with a Yalie. In a way this is the real rock bottom.”) Whether in her personal or professional life, Hood is often “the first trans woman they’d encountered, or so they told [her].” She ends this section with an allusion to the book’s third assault, a gang rape in 2016. Part IV takes place around December 2023 with references to the genocide in Gaza and follows the “we” of Hood and Helen, the first therapist she’s ever met with, in some twenty-five or so weekly sessions. Hood presents curated transcripts during which she not only recounts the horrific attack but also shares again and again her anxieties about the writing and publication of the book we are reading.

Sound like a lot? It is. That’s the point.

Two issues arise when confronting, or being confronted with, Trauma Plot. The first could be stated: As a text, it is promiscuously digressive, polyvocal, and sort of messy, calling on those who encounter it to ask: How should a grief memoir be? This is a formal and familiar query—can language suffice as a container for trauma—but it is also, urgently, a relational one: How should readers and critics receive the suffering of others, and what does a post-traumatic account demand of its audience? These aren’t my words, but rather Hood’s, in an essay in the pages of this magazine from 2024. And so the second issue might be: What happens when a talented critic writes an extremely personal and ambitious book that insists on being read both as a work of criticism-protest and an attempt to expand our very notions of what a trauma memoir can do?

THE MOST CONVENTIONAL of the narrative sections, Part I proceeds with clear momentum toward a defined event (the evening’s party, for which Jamie H. buys the flowers herself) and a metaphysical crisis (the reckoning with the Specter). The personification of trauma is deft and fresh: “At moments she liked thinking she was no longer wading through the waves of her life alone, that it accompanied her as a sort of guide, but in her heart she understood it wasn’t right, the Specter’s being there, it wasn’t sanitary somehow.”

The last twenty pages of Part I are brilliant. Having introduced the reader to a string of objectionable men—a sexist, scatologically obsessed fellow grad student, a shlumpy student-marrying professor, an old boyfriend whose theses about her defectiveness he “always seemed to be nailing into the door of their relationship like Martin Luther at the church in Wittenberg”—Jamie H. is stopped on her walk home. It’s a carload of drunk men “heading back to Medford, Melrose, maybe Malden.” The frightening, grossly common street harassment is expertly distilled—a planetary-wide form of male aggression typified here by a particularly pea-brained species native to those alliterative habitats.

“Don’t you talk, bitch? We’re talking to you.”

“I’m good.”

“You’re what?”

“I’m good.”

“The fuck? . . . Fucking faggot.”

After Jamie H. picks up a bottle they’ve tossed out the window and throws it back at the driver, she runs away and hides under a car, where she finds herself grinning: “She felt a strange prick of desire, elliptical: relief’s thundering illogic. Her body warmed to itself, puddling against the asphalt.” At home, heart pounding, Jamie H. suddenly senses what she needs to do: “flagellate the marionette of her self into its original knowledge.” What follows is the most riveting resurfacing of a buried memory of sexual abuse I’ve ever read, somewhere in between Proust’s madeleine and Molly Bloom’s Yes—only Jamie H. shouted No—evoking the tentacular reach of trauma, its squashing together of violence, fear, and stimulation. (The passage may owe something to Annie Ernaux’s final lines about masturbation in Shame.)

As the climactic memory washes over her, we’re let loose in the dance club where Jamie H. met the Diplomat. “I wanted him. I won’t deny it,” she writes. “He asked if I liked being a slut. I said don’t call me that. He said he’d still fuck me. I said we’ll see, but I was drunk on his desire. I was also just drunk.” It’s a good example of Hood’s stone-faced style of self-appraisal. Her disarming honesty allows us to feel the full force of the brutality visited upon her, upon anyone who can’t mime the part of the unimpeachable victim.

TRAMUA’S REAL THREAT TO STORYTELLING ISN’T, I think, its tyranny of backstory but something much more existential. Take me. I’ve always known I wanted to write, but for just as long I’ve struggled to tell a good story. A loquacious pedant-father and a favored older brother inhibited me, for sure—I listened more than I spoke, and mostly joked when I did—but I also held in the core of my being an explosive story (first one, then more) that I physically could not narrate. A trapped story is a black hole.

By falling outside our tolerance window, the traumatic event is inexplicable, unspeakable. When something can’t be verbalized, it’s like an undetected parasite swimming through the bloodstream. None of the items on the trauma laundry list with which I began this review are good for the building of character, the assembling of arcs, or the resolving of conflict. Trauma scrambles neural networks and narrative frames. Shame isolates. Agency is lost, desire stunted. Recursion and repetition replace linearity and surprise. Time warps, feelings dissociate, action stalls. We are less ourselves, more our reaction to what happened to us, a profile of behaviors we share with other sufferers: we withdraw, angry yet numb, and grow self-involved and self-destructive. Ambivalence owns us. We become what I call autraumatons.

Like a spirit in a nineteenth-century photograph, trauma must be staged for its haunting visage to be convincingly captured in prose. Hood understands the challenge: Trauma “disorders narrative, for what is a story without time? How can a woman made into meat speak? Does abjection have its sort of character? These are irrevocable absences. They snip plot’s thread.” But the key question—no, the answer—is how Hood will overcome these obstacles in telling her story. As far as convention goes, the classic rape-memoir strategy to deal with trauma’s assault on narrative is to use the churnings of the justice system to frame and drive the action, as in Alice Sebold’s Lucky or Chanel Miller’s Know My Name, doling out the destruction in doses, cutting away to scenes of their narrators at home or with friends, before and after the crimes, where they came from and where they’re trying to go. (Like Sebold and Miller, Jana Leo in her less well-known Rape New York also begins with the assault, follows the trial plot, though she then attacks the hydra-headed patriarchy when she sues her criminally negligent landlord for failing to secure the building despite knowing about prior rapes that occurred in it.) When a memoirist eschews the police-procedural format, she will provide a substitute narrative engine; in Margaux Fragoso’s Tiger, Tiger, for instance, a book that like Hood’s makes heavy use of diaries, there is a highly novelistic journey into the abuse, a dwelling there, and an escape from it. And then there’s the slim essayistic memoir, like Raymond M. Douglas’s On Being Raped, which pierces the weighty topic like a sharp lance.

Hood isn’t as interested in the overcoming as much as in the staying stuck, and Trauma Plot challenges our need for conflict resolution, arc-assembling, and character-building, as if these are naive constraints, unfairly imposed. This is bold and valuable. It is also, even with the simplest subject matter, a risky proposition. Any genre thrives in the capsizing of its expected tropes, and I’m all for, say, filmmaker Céline Sciamma’s exhilarating rejection of what she calls “the scam” of historically male storytelling, or Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” but the greater the subversion, the higher the bar becomes for success. At the start of Trauma Plot, Hood declares war on a literary-critical discourse and our reactionary culture, but as the story unfolds the book actually comes to fight on a second front. Rather than writing against a sexual-predator president, or rank-and-file misogynists, or retrograde critics (who’ve already decided their stance on trauma and won’t pick this up), Hood mounts her most significant offensive on readers of the genre in which she works.

Hood appears to have crafted a self-contained Part I that observes the Aristotelian unities so she can draw readers into Part II, which relies on “compulsive, meticulous, and tediously recursive” diaries, commencing the book’s process of disassembling itself. She opens firmly with a Didionesque bafflement at the gyre widening in the wake of the Boston Marathon Bombing (which she compares to the Manson murders) and reflects on how it became stitched into the patchwork memory of her second rape. There’s a chillingly evocative scene of Hood having to accept an hour-long car ride home from her assailant the morning after he raped her. NPR plays on the radio while he too natters on. It’s suffused with the dread and nauseating surreality of those stunned moments that seem to run for days. Outside her house, Hood crosses paths with a mother and her baby, causing her sense of shame and isolation to deepen further: “I thought how precious it would be to live through one uncontaminated morning, and how awful that they’d been forced to witness me. . . . I felt badness leaking from me.” It is a gutting moment.

In the wake of that second assault, Hood withdraws: “I abdicated myself: I was a void in the shape of a woman.” A sharp description of a human being drained of meaning, like a hunted animal hung up to dry. Yet it signals the beginning of many clipped statements of feeling. It also stands as a worrisome admission for an author: voids and black holes possess no center and disappear light. I started to struggle in the middle of Part II. Despite all the disclosure and intimacy on the page, I didn’t feel as close to Hood as I wanted. I figured this was the point: trauma pushes other people away, bringing a leaden shroud of guilt and shame down around the survivor. I wanted to see Hood in more scenes. But trauma kneecaps movement, I told myself. I wanted her to interact with textured characters. But the point is that trauma isolates. I was glad when “the Professor,” a married man who says their sex is “like TNT,” entered the picture, pleading for more pyrotechnics, and Hood broke things off with him (he reappears to great effect in Part IV). This action, in the context of a relationship, showed me who she was rather than keeping me within the confines of her narrating mind, all post-traumatic points be damned.

WHILE DRAFTING THIS REVIEW, you consider backing out. Like Hood to the reader about her book, you express anxiety over the piece to your editor, also a cis-het white man. This is a vulnerable book, and you feel vulnerable reviewing it. You both agree that the task of literary criticism is to take books seriously, engage and grapple with them fully. What matters is that the critic appreciate what’s at stake in the work. You mention to him a curious and funny fact: so far, there’s only one review of Trauma Plot in a major outlet. Funny because Hood writes that the last thing she needs is “some ‘post-feminist’ in The Atlantic telling me I can’t parse the difference between fucking some guy I regretted waking up to and being roofied and passed around by five men in a trap house.” (The actual review is very kind.) It’s curious because Hood has been interviewed by many outlets, which, since you work in book publishing, you know is an easy way for an editor to cover a deserving book without having to get a critic on board for the full grappling and engagement. You want to do just that. One of the lines in Hood’s book that resonates the most with you is: “I knew violence from the time I was six, which is to say there was no before my violation; I have no origin that precedes trauma, because the formulation of my ego was bound up in it, so I felt, yes, of course this is the matter of my life.” Mon semblable, — mon sœur! You decide to stick with it.

You feel the accumulating simple subject-predicate sentences fall heavily in Part III, like some brute’s boot steps down a hallway. You marvel at Hood’s faithfulness to her diaries—she scrupulously dates them in footnotes—but once again you frequently feel far away. You wonder if it’s because you’ve been sexually traumatized and sitting amid so much rubble is upsetting, or if this approach is claustrophobic because diaries can, if they’re like weather vanes attuned to the shifts in one’s self-states, shrink the world to the narrowest letter in the alphabet. Hood understands your predicament: “You hate this inward turn: the machine-gun fire of the I, I, I, I.” She later writes: “You’re enslaved by what Plath calls the ‘shut-box’ of personal experience. ‘I’m falling into the pit,’ you write, ‘I must stop looking inward, I must learn to write what is worth someone’s time.’” You feel trapped by this admission. You’ve been placed in a shut box and the person who put you there, Hood, effectively says, Here I stand; I can do no other. The Hood of the diary wants to stop looking inward, but the Hood of the memoir refuses to grant this wish so as to remain true to Hood the diarist. Which Hood should you take more seriously?

Halfway through Part III, Hood the memoirist interjects: “I wonder if my writing this book—digging through your history in this way—is unethical or dishonest, if I’m exposing you. . . . Is it my job, or perhaps my crime, to assemble plot, to force on your behavior an ineluctable causality? It’s entirely possible I gather your confessions from the wreckage of your accounting to pathologize you, to frame your actions like the motion of a rubber band snapping back.” You’re not sure about that rubber-band business, but you believe it’s Hood’s job to assemble some kind of plot and that to do so wouldn’t necessarily require a criminal level of imposed causality. Again you’re intrigued by Hood’s faithfulness, in this case to her former self, but you believe a writer ipso facto is “unethical” or “dishonest” in the same sense that a sleight-of-hand artist is “deceitful.” Writing is the most selfish act when everything, other people and your own experiences, becomes copy. Of course. Unless the writing, with all it sacrifices, is done for one other person, the reader. In which case, it’s magic.

IN PART IV WE JOIN HOOD on the couch—or rather on Zoom—where, during her thirteenth session, Hood realizes: “I’ve been ranting for some minutes now and apologize to Helen, who raises her eyebrows. This is the space, she says.” Hood in her self-awareness could no doubt anticipate what’s coming next: Is her book the space? It’s so audacious to end her memoir written against trauma-plot skeptics and writing-as-therapy deniers in therapy that we’re fascinated, first by the conceit and then by its progression. Yet there remain the issues of quantity and quality. This final part is daringly the longest, and a good deal of the sessions are given over to rehearsing arguments she polished in the introduction—“I yammer on awhile about the cultural backlash against #MeToo, and before I know it, we’re at time”—and fretting over the book she’s working on. Her interrogations of trauma-writing are often piercing, but the question marks in their sheer volume come to diminish one another’s effects.

“Have I adorned my trauma effectively enough that the labor will be recognized, or will I seem to be merely exorcism, purgative?” she asks. “But why should I make my rape book artful? Why be cowed by this obligation. Shouldn’t trauma be a mess? What if I let it be a

performance, a public flaying—is it not better to provoke than to appease?” The meta-nonfictional trajectory of the book reaches its zenith in this section. While the deconstructions can be insightful, there’s something maddening about these exaggerated if not false binaries—artful versus messy, provocation versus appeasement—being foisted on us here, so late in the game, even if that’s how it happened in real life. In another register, Hood reflects toward the end: “Then there’s so much I’ve kept out of the book, which pains me. The joy isn’t there, I’m sad to say, and there’s plenty of it. How strange: I protect my love and pleasure from view, but how right, too. Those things are mine. I must keep them close. The rapes were only what was done to me; I don’t own them; they aren’t my cage.” Here, we must object. In any memoir, but especially one in which ruthless self-examination is an article of faith, we’re upset that humanity—pleasure and love—has been withheld from us. And not by trauma this time but by authorial choice.

Hood’s mind is fast and intelligent, but we might wish, for our own sake, that Helen employed a more interpersonal approach to the therapy, slowing things down. Hood tells her: “I look at the aftershocks of my trauma, it’s quite easy to establish continuity between my behavior and what was done to me.” Hood has broached the subjects of gray areas and revictimization before, with striking precision and rare candor, and we sense even more shrewd observations await us, but we don’t tarry here long. Hood says being “knee-deep in sex trauma” stunts her desire for intimacy with her boyfriend K., but their relationship never assumes a distinct shape and feel. And she talks about her therapy with her close friends, the writers Charlotte Shane and Harron Walker, but we don’t discover what they say, or what role they’ve played in her life. Hood says she thought she would include “Charlotte and Harron more extensively in the writing of the book” but after sharing the second section she felt “disinclined to shove all my tedious trauma off. I don’t want them to turn from me; I know the impossibility of bearing another person’s wreckage.” This is hard to read. One thing Hood does not mention in sessions or outside of them is another person’s memoir about rape and trauma. (Her review that was quoted from earlier was of Blake Butler’s Molly.) Hood discusses the writing of Rebecca Solnit, Bhanu Kapil, Monica Lewinsky, and Katherine Angel, but she doesn’t engage with a nonfiction book telling a story like hers. It’s a curious omission, particularly in light of her many confrontations with narratology: “I haven’t miraculously healed myself. It’d be so easy to write that memoir—one where I’m beyond it all. Easier still to write the story where I go, oh dear, I was so helpless, and so perfect, and don’t you feel bad for me?”

There are inherent challenges to therapy scenes. Therapy is mostly undramatic—Good Will Hunting, In Treatment, and Couples Therapy notwithstanding—and there’s also the danger that our own revelations might be less revelatory to the therapist or reader who has already picked up on our unconscious patterns. The bigger issue: if we were to read transcripts of every session we’ve ever had, they might be illuminating, and not a little embarrassing, but they wouldn’t be the therapy or measure what took place. Not just because what’s unsaid is as important as what’s said, but because therapy isn’t only about speaking, it’s about being heard. The sui generis arrangement over time comes to alter our relationship first to the therapist—and then to others outside the room, or off Zoom—because this person, perhaps for the first time in our lives, is listening to us with one intent: to help. And this elemental aspect of therapy is perhaps even more slippery to set into words than trauma itself.

Still, by ending Trauma Plot this way and by continually choosing risk and ambition, Hood has accomplished a rare feat: she has expanded the possibilities for a trauma memoir. We’re excited to read more of her, to be with her outside the self-conceptions she’s formed within her diaries and her sessions, to see what she does next in the world. For now, though, we’re at time.

Elias Altman is a partner at Massie McQuilkin & Altman Literary Agents.