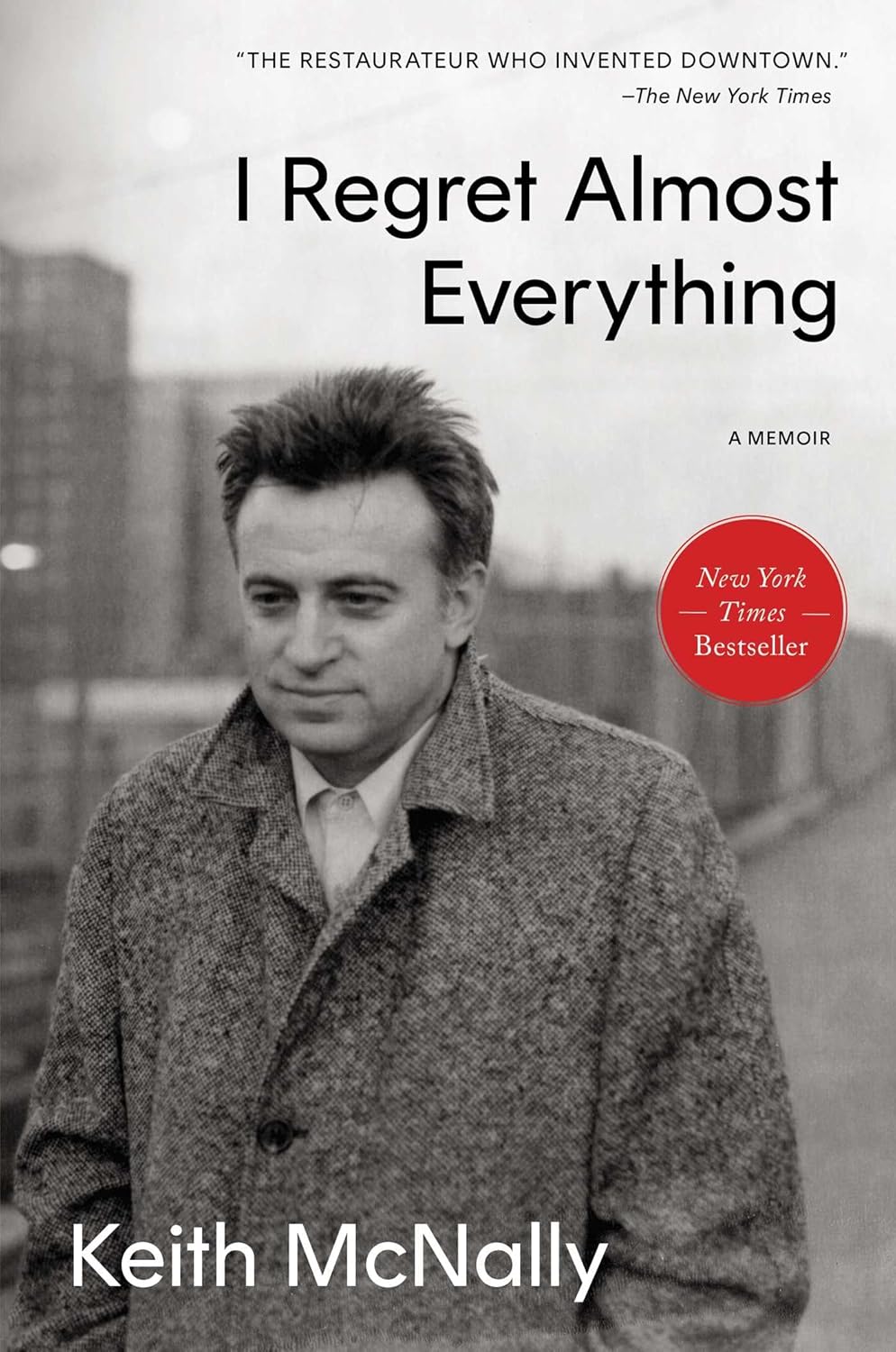

SELF-PROCLAIMED “DEADBEAT NEW YORK RESTAURATEUR” Keith McNally is not a man at peace with himself. This assessment requires no great leap of interpretation, given that his memoir, I Regret Almost Everything, opens with his 2018 suicide attempt. In McNally’s telling, he had been on top of the world just two years prior: happily married and with his eight Manhattan restaurants making $80 million a year, he and his family flitted between their homes in New York, Martha’s Vineyard, London, and the English countryside. The overdose of sleeping pills that would land him a two-month stint at McLean psychiatric hospital was part of the grim aftermath of a painful divorce and debilitating stroke he’d suffered in 2016. While doctors were initially at a loss as to what caused this healthy, nonsmoking sixty-five-year-old’s stroke, McNally concludes it was triggered by one of the convulsive coughing fits he was often seized by when opening a new restaurant. Overnight, he became confined to a wheelchair and deprived of language to the point that “speech suddenly seemed like a divine accomplishment.” Restaurants made Keith McNally, but they may have also been his undoing.

The suicide attempt was also the trigger for his memoir, which loosely knits together stories of his life, many of which he’s previously shared on Instagram to his 162,000 followers. There, he fires off promotions of his business (“If you ever commit suicide please make sure that Balthazar’s Steak au Poivre is your last meal”), tributes to friends (“Padma [Lakshmi]’s breasts are sensational. To call them offensive is itself an offense. A fucking almighty one”), medical advice (“STOP ABORTION AT THE SOURCE. Vasectomies Are Reversible. I Had One Three Years Ago and Absolutely LOVED IT. Please Help Make Vasectomies Mandatory For All Men”), and travelogues (“Photo taken from my hotel in Rome. I don’t know why, but sleeping so close to the 2000 year-old Pantheon gives me indigestion”). For the man behind the empire of New York institutions including the Odeon, Minetta Tavern, Café Luxembourg, and Pastis, McNally posts with the irreverence and abandon of a young person with nothing to lose.

His book has the makings of a tell-all. There are splashy stories about his friendships and encounters with the likes of Anna Wintour, Lorne Michaels, John Belushi, and Robert Mapplethorpe; Warhol, Basquiat, Schnabel, and Prince make appearances. Compulsively readable, these anecdotes deliver the atmosphere that diners have come to expect of McNally’s hospitality: decadence and glamour made accessible through a light touch and a louche, punchy style. There are the industry feuds and crossovers—with his brother Brian of Indochine, Drew Nieporent of Nobu, Michael Chow of Mr Chow, ex-employees Riad Nasr and Lee Hanson (the eventual founders of Frenchette), and Rose Gray of London’s River Cafe. There’s his courtship of the late billionaire landlord Bill Gottlieb, who “dressed like a slob and carried all his important papers in a shopping bag,” for the lease of what would become Pastis. And there’s Madonna at the door of Nell’s, the club McNally once co-owned, calling him a “fucking bastard” for not waiving the five-dollar entrance fee. The candor with which he narrates these celebrity run-ins makes it believable when he professes his ethos of treating special people regularly and treating regular people specially. (“There are two kinds of restaurateurs: those who identify with the staff and those who identify with the customers,” he writes, casting himself in the former camp.)

But what’s most surprising and revealing about the book is its earnest attempt to account for all that McNally has lost. The narrative spirals around his stroke, divorce, and suicide attempt as he retraces his working-class roots in London’s East End, his move to New York, and the development of what has since become his dynastic restaurant business. McNally’s father worked as a waterfront laborer, his mother as an office cleaner, and they limped through a joyless, five-decade-long marriage; intimidated by the culture of fine dining, they never once took the family to eat in a restaurant.

McNally recounts his early life in remarkable detail and charts his acculturation into the early 1970s London theater world through his friendship with English playwright and writer Alan Bennett, whom he met as a sixteen-year-old actor in Bennett’s play Forty Years On. “One of the things I most admired about Alan was his instinct to distrust the gratification he received when proven right,” McNally writes in homage. “He was highly suspicious of certainty. (Turning down a knighthood in the eighties, he would even question the glimmer of pleasure he felt by refusing it.)” McNally writes of the contrast between his parents’ prefabricated house in Hackney, with its “cheap linoleum” floors, and the “Bloomsbury feel” of Bennett and theater director Jonathan Miller’s homes, which were filled with books, sculptures, and paintings by Vanessa Bell and Roger Fry. The burnt yellow of Bennett’s sitting room walls left such an impression on McNally that he has been trying to re-create the exact shade in his restaurants for almost half a century since.

If the most vivid relationships in the book are his friendships with male intellects and influences—Bennett and Miller, Oliver Sacks, Christopher Hitchens, Tom Stoppard, and Robert Hughes—McNally can tend to draw the women in his life in one dimension (“sultry,” “low self-esteem,” “sensual”). He is forthcoming about his failures and regrets as a husband, father, brother, and son, even as he shares sexually and emotionally intimate encounters with his second wife, Alina, in jarring detail. At times, his book reflects all too clearly how self-loathing can sour into a compulsive need to force a discomfiting level of intimacy in order to be liked. This impulse to please can backfire, and McNally is often the least considerate of those closest to him. When his oldest brother Peter dies, McNally writes that “for someone with such fierce independence, he died the kind of death he would have been ashamed of,” before going on to quote an email from their brother Brian describing in visceral detail the realities of Peter’s disintegrating body and uncontainable bowel movements. It does not seem to occur to him that sharing such details might be the exact kind of shameful violation of Peter’s dignity and privacy that he had a sentence prior remarked on.

The memoir was born out of Bennett’s gentle suggestion that McNally “write things down” during his post-suicide-attempt-recovery at McLean. As such, it is a project baked in therapeutic intent. When McNally begins meeting with a therapist at the psychiatric hospital:

I cringed at the idea of “opening up.” At the same time, I was anxious to talk about myself. Dying to, in fact. I felt competitive and wanted to show off and impress the shrink. But like everybody I’m anxious to impress, Bonnar wasn’t having any of it. That didn’t stop me from trying. As the words tumbled out, I felt simultaneously fraudulent and sincere, totally genuine and a complete phony. I felt like myself.

McNally is full of contradictions, eager to reveal himself and readily offering such flashes of insight into his own character and shortcomings, but unable or unwilling to investigate further. When McNally’s first wife initiates divorce, the news comes with a dull thud, narrated in two brief lines: “When I returned to Paris, Lynn asked for a divorce. Although devastated, I couldn’t blame her.” It’s unclear whether this is evidence of uncharacteristic discretion, but he comes up against another block when his mother dies. Upon receiving the news, he remembers the opening words of Camus’s The Stranger, “Mother died today,” which he’d often repeated to numb himself for when it would really happen. “And it worked. The day my mother died, I didn’t feel a thing.” For a blow-by-blow account of a life coming undone, the book tends to slip past grief.

McNally’s failures to make meaningful links between past and present, emotion and action, action and consequence, reveal a tendency to evacuate rather than metabolize his experiences. This can make for good entertainment, but not great art. I wondered what kind of book he might have written if he’d faced what he calls his “Zelig-like” character as a starting point for self-examination rather than as a deflective punch line. (But if he were the person to do that, there would probably be no Pastis Miami.) The closest he comes to this might be when he’s rereading Pride and Prejudice at McLean and realizes how frequently his assessments of Austen’s characters shift. He quotes the editor Clifton Fadiman: “When you re-read a classic, you do not see more in the book than you did before; you see more in yourself than there was before.”

After seeing his youngest children for the first time after his stroke, McNally weeps “for the first time in twenty years.” And at the psychiatric hospital, he begins to have a recurring dream of playing soccer with his son. “There’s no hint of my paralysis as eleven-year-old George and I are running around laughing and tackling each other. I’m deliriously happy until I wake up and realize that it’s just a dream. And then it’s agony.” The dream initially taunts him with all that he has lost—a certain vision of fatherhood, his health, his capacity to move and to play. But by the time he leaves McLean, and after more than seventy sessions of psychotherapy, he begins to view the dream differently: no longer as a nightmare, but as a memorial, suggesting that McNally may be learning to mourn after all.

Hiji Nam is a writer and candidate at the Institute for Psychoanalytic Training and Research in New York.