“A SALESMAN HAS TO SEE PEOPLE AS THEY ARE,” says the protagonist of Helen DeWitt’s 2011 novel, Lightning Rods, a satire about a failed door-to-door salesman who invents a business model that winds up reordering the modern workplace. “No matter how badly people want something,” he explains, “if they don’t want to be the kind of people who want that kind of thing, you’re going to have an uphill battle persuading them to buy it.”

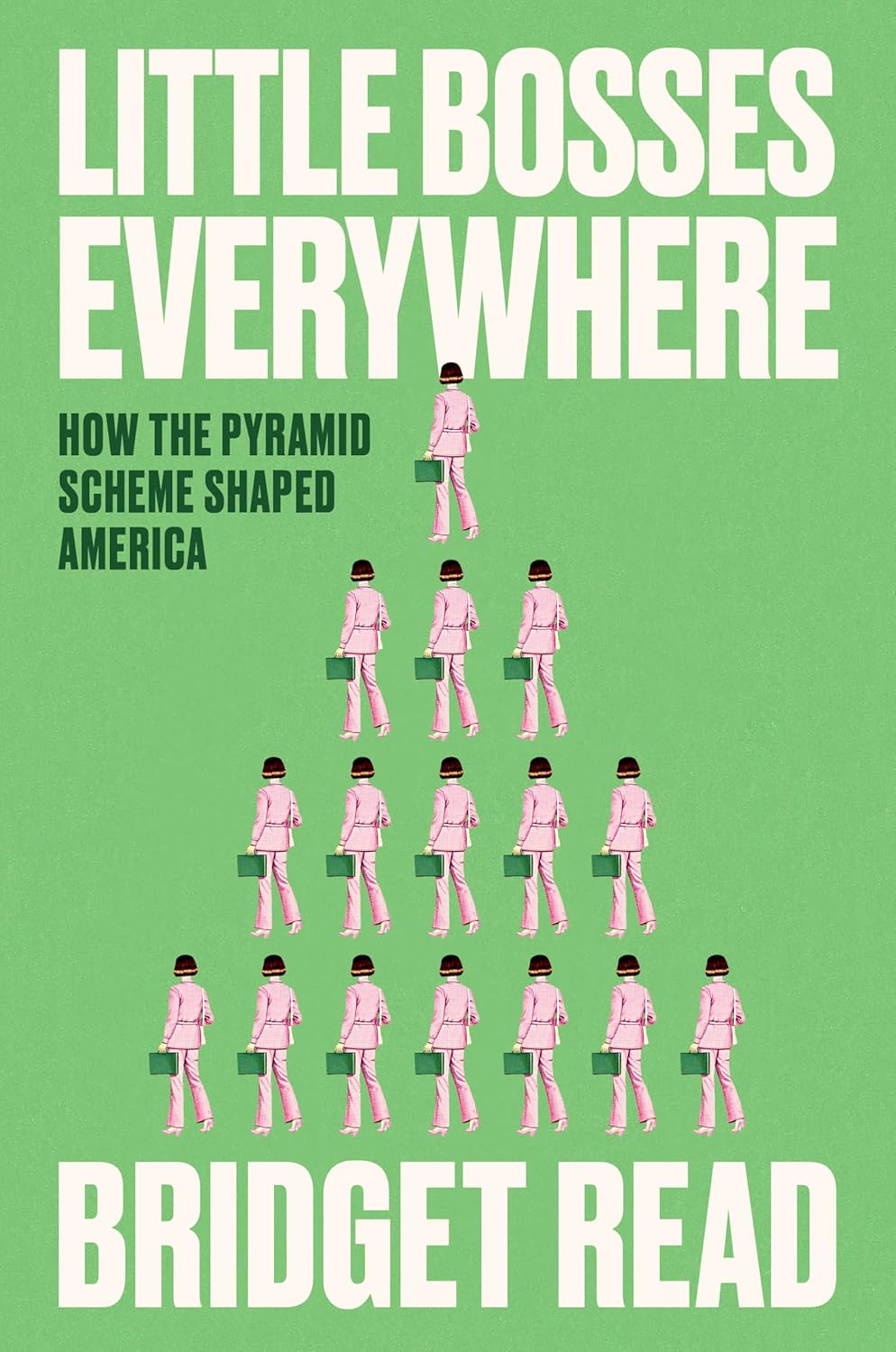

There are many salespeople in Bridget Read’s Little Bosses Everywhere,all of whom toil in an industry designed to obscure this clarity of vision. They work in multi-level marketing (MLM), the industry comprising Mary Kay, Herbalife, Amway, and some seven-hundred businesses that purport to sell their products in person-to-person interactions called “direct sales.” Officially, MLM sellers generate revenue by ordering lipstick or diet drinks or essential oils at a discount and selling them at profit. In reality, MLMs quietly encourage another way to make money: recruiting other salespeople to buy the first seller’s products and try to hawk them to someone else. Only the rare salesperson cuts through the obfuscation to apprehend their true target: people who want so badly to be their own boss that they’re willing to pay for it. Most of these subordinates wind up hemorrhaging money on diet drinks they’ll never offload. The guys who came up with this model in the 1940s called it a “profits pyramid.”

MLMs present their sellers as modern incarnations of the kind of salesmen DeWitt’s protagonist Joe used to be: the door-to-door pushers of encyclopedias or Electrolux vacuum cleaners, the nobler descendants of the Yankee peddler, the sly archetype of American hustler depicted in Herman Melville’s “The Lightning-Rod Man.” But as Joe learns, pavement stomping is arduous and often unsuccessful. He escapes the schlepping life with a clever bit of rebranding: disguising a surely illegal idea—sex work in an office setting involving architecturally complex glory holes—in respectable jargon, thus making the forbidden seem suddenly plausible, or at least plausibly deniable. Read argues, persuasively, that multi-level marketers have spent the past century doing essentially the same thing, deploying what one ideological ally called a “new grammar,” a benign-sounding lexicon of buzzwords and misnomers whose mystifications run so deep they obscure even the very idea of “sales.” (MLMs define sales not by the amount their customers spend, but the amount their own sellers buy.) This “impressive feat of doublespeak,” Read writes, has concealed how these companies operate, shielding the industry from regulatory scrutiny, while allowing a generation of New Right reactionaries to reorder the workplace and rewrite American law.

Read never mentions DeWitt, though some of the schemes she describes are nearly as absurd (at one point, salesmen pay $1,000 each for a retreat where they are punched, locked in cages, shut in coffins, and “strung up on a crucifix” ostensibly to make them better at selling makeup). But the unsettling goofiness of MLM, she suggests, has only aided its camouflage. For all its brazen graft, the industry has been lumped in with “other factions of this country’s colorful fringe,” becoming, like Scientology, some cross between “a cult, a crime, and a joke.” Read describes her study as a small corrective. “This book sets out to look directly at multi-level marketing,” she writes, and see “what it actually is.” It doesn’t take long to see MLM as “one of the most devastating, long-running scams in modern history”—a feature of American life that she has little hope will ever end.

Read traces the lineage of MLM back to the ’40s, when Carl Rehnborg, an “extreme nutrition hobbyist” with an affinity for bad ideas, founded Nutrilite, a vitamin business involving an alfalfa concoction. The early twentieth century vitamin market was a boon for grifters. Though supplements offered few proven benefits to the healthy, the country became fascinated by these “tasteless, invisible, immeasurable substances,” as historian Catherine Price put it, “that needed to be eaten in some unknown amount every single day.” The “language of vitamins,” Read writes, fed the national appetite for magic solutions and miracle cures. (“Americans want to believe in tonics,” one FDA veteran remarks, “they have always believed in tonics.”)

Unfortunately for Rehnborg, no one believed in his tonic until two distributors—broke eugenicist William Casselberry and scam-y funeral marketeer Lee Mytinger—devised a foolproof strategy to offload the vitamins no one wanted. They came up with a different kind of miracle cure, a get-rich-scheme to market Nutrilite not only as a vitamin, but also as a business opportunity. They would recruit an endless chain of salespeople to buy the vitamins and sell them to other salespeople, who would in turn recruit more like themselves. They called their plan “The Plan.”

The Plan was inherently self-replicating; it incentivized recruitment, replenishing failed salespeople with a new batch through a process that a later MLM called “duplication.” It worked for Nutrilite, which became a multimillion-dollar business within years. But The Plan perhaps replicated too easily: any savvy seller could leave to start their own business. Rehnborg realized as much when his partners started their own makeup-based MLM, “Magicare.” Others followed suit, starting new endless chains, which in turn spawned other spin-offs: Nutrilite begat “Numanna,” then “Abundavita,” which begat “Nutri-Bio,” which led to “Holiday Magic,” later knocked off by “Koscot,” and its offshoot, “Dare to Be Great.” Each iteration adopted its own version of The Plan and its own goofy newspeak. Depending where they sat on the MLM family tree, sellers might be called “sponsors,” “consultants,” “key agents,” “Organizers,” “Generals,” “Masters,” “Rubies, “Emeralds,” “Diamonds,” or “kingpins.” The names differed, but the premise didn’t: if the salesperson made money, and most did not, they earned it by recruitment. The product was tangential—so much so that, when Amway first started out, its founders didn’t even have one.

Read’s book reads as a well-paced polemic, crescendoing as MLMs multiply across the twentieth century, creating new scams with novel buzzwords that send more salesmen careening into debt. She makes a compelling case that nearly every American MLM can, in some form or another, be traced back up the pyramid to Rehnborg and his middling vitamins. And some of the best reveals of her reporting arise when she uncovers surprising connections, including a direct link to Mary Kay, whose founder claimed to have devised her business model on her own. But the book’s most interesting feat is its semantic dissection of direct selling, laying bare how the language of MLM drew on the self-help texts of the early twentieth century to translate post–New Deal reactionary conservatism into a common tongue aimed at the working class.

THE SEEDS OF CONSERVATISM were there from the start. Rehnborg met his partners through a sales course taught by Dale Carnegie, the author of How to Win Friends and Influence People, which attributed success to “personality” above all else. (Carnegie also profited from a bit of deceptive wordplay; his last name was originally spelled “Carnegey.”) Read frames Carnegie and his peers as modern evangelists of what William James called “New Thought,” the American woo-woo obsession with psychological tonics, like curing ailments with your mind. Carnegie-style “money mystics” like Napoleon Hill (Think and Grow Rich) and Norman Vincent Peale (The Power of Positive Thinking) instead pitched wealth-accumulation as a feat of individual will—a bootstrapping ideology that ran through early MLMs, whose founders all read the same books and often wrote some themselves. (The man behind Koscot finally cut to the chase when he started Dare to Be Great—an MLM whose product was self-help.) By emphasizing individual responsibility, MLMs could blame the salesmen for any failure to succeed. They could also skirt worker protections. Years ahead of DoorDash and digital media companies, MLMs began by classifying their sellers as “independent contractors.” Relying on freelancers allowed Nutrilite and its successors to shirk employment benefits while operating outside twentieth-century labor laws.

No MLM was more central to this political project than Amway, a Nutrilite spin-off whose founders, Jay Van Andel and Richard DeVos (ex-Goldbugs, Peale fans), became a “crucial connecting force in mobilizing the coalition we now think of as the New Right.” Economic conservatives, who saw the New Deal as “a capitulation to organized labor,” needed new language to vilify government intervention and “get workers to root for the boss.” Amway took up the cause—coining more cryptic argot (IBOs, BVs, PVs, LOS, LOA), while the company’s propaganda arm “pumped out masses of literature” about unburdening the “supply side” from the weight of regulation. All the while, Amway’s leaders camouflaged their agenda in the vernacular of patriotism (including an annual “mass ritual signing of the Declaration of Independence”) and cozied up to politicians like Gerald Ford. The founders of the so-called American Way, Read writes, became “spokesmen for the American Dream.”

Anyone passingly familiar with said Dream can guess what happened next: Amway used its political clout to shield its shady business model from regulatory oversight, decrying the federal “nanny state,” while subtly rewriting the narrative of MLM to distinguish itself from its more overtly scammy peers. As prosecutors cracked down on MLMs, Amway’s founders propagandized against the “bad apples,” whose “pyramid sales schemes” destroyed the credibility of good businesses like Amway. In a move so brainless it approaches brilliance, Amway scrubbed the word pyramid from its own brochures in favor of a whole new geometry based on “circles.” Now, its salesmen no longer stood atop a pyramid, but at the “center of a wheel of other circles,” whose spokes represented the underlings they scammed.

As Amway publicly derided “pyramid sales,” of course, the company was privately protecting them, gutting anti-pyramid legislation to shield itself from regulation. (The governor of Massachusetts signed one such bill with an Amway-branded pen.) Even when the Federal Trade Commission finally charged Amway in 1978, the company managed to transform the case into the industry’s single-most effective defense. Though the judge convicted Amway on a single charge, he cleared the company of running a pyramid scheme—creating the “Amway rules,” a legal definition that distinguished the illegal pyramid scheme from the legal MLM, enshrining Amway’s “bad apple” fiction into federal law. Amway’s “distinct business language” of circles and acronyms had apparently lent it “a protective layer of mystification” too opaque for prosecutors to penetrate. Their defense has become “boilerplate” for the countless MLMs that have popped up since.

IT GOES WITHOUT SAYING that Read’s well-reported, entertaining history—of a bluntly predatory business model built on the promise of self-driven social mobility that materializes for only an elite few—is a parable about the United States. And one need not look far for connections between multi-level marketing and the broader arc of American corruption, be it the OneCoin crypto scam (marketed as an MLM), or the NXIVM cult founded by ex-Amway salesman Keith Raniere. But amid a glut of recent books promising to distill America’s present political turmoil into a single subject, Read’s pitch is more modest than most, and more credible for it. She notes, for example, that MLMs did not single-handedly carve out the “independent contractor” loophole in the wake of the New Deal. Nor were they the only ones to peddle supply-side propaganda, or lobby agencies for federal carve-outs, while lambasting the FTC. But in laundering conservative talking points through a shadow workforce of unregulated laborers, MLM propagated a model since replicated across the American economy—from the Reagan revolution (his MLM-style fundraising operation was devised by Richard DeVos) to the patriarchal gig economy envisioned by Project 2025. Seen through the right lens, they all appear part of the same Plan.

A savvy publishing salesman might have preferred Read to have marketed her book more like Rehnborg, with a simple diagnosis suggesting a simple cure. But Read does not posit MLM’s quacks as modernity’s only cancer, so much as “creators of distinct strains of the same disease”—a pathology that has infected, if not directly caused, economic ailments from the collapse of the social welfare state to the election of a snake oil salesman nursed on Norman Vincent Peale. (Trump not only installed MLM heiress Betsy DeVos in his first cabinet, he marketed two MLMs himself.) Read’s diagnosis is instead more complicated, and her outlook is much more dire. If anything, she is peddling an anti-quick fix: a deeply skeptical survey of a disease not so much without a cure, as without the will to administer it.

Towards the end of the book, the author recounts the grim track record of anti-MLM activism. Despite a brief crusade by hedge funder Bill Ackman, a president self-styled after FDR, and the first FTC chair in a generation to seriously combat corporate greed, Congress never passed the PRO Act and America put an MLM spokesman back in office. One recurring character, Robert FitzPatick, a prolific critic who has called for an outright ban on MLM, is clear-eyed about his likelihood of success. “You don’t have to have hope to speak the truth about what multi-level marketing really is,” he says—advice that could apply just as easily to the US administration in power. Perhaps Americans just don’t want to be the kind of people who regulate quick fixes. The epilogue of FitzPatrick’s book is titled, “No Hope and None Required.”

Tarpley Hitt is the author of Barbieland: An Unauthorized History, forthcoming in November.