SINCE LEAVING ANTIGUA FOR THE UNITED STATES in 1965, at the age of sixteen, Jamaica Kincaid has written fiction, essays, and memoirs that mull over her inheritance as the reluctant daughter of the British empire. She is best known for her slim novels Annie John (1985) and Lucy (1990), about a rebellious girl growing up in the West Indies and an obstinate young woman who works as a maid in New York, stories that closely parallel Kincaid’s own biography. Her most compelling work has emerged from memories of her Antiguan childhood and her relationship to her dominating mother, and she has spent the past five decades writing from a position of filial defiance. Precocious, petulant, and at times devious, she has refused to play any game not of her own invention.

From the beginning, rather than write as Elaine Potter Richardson—the name her formidable mother would have recognized—she chose a nom de plume: Jamaica, a nod to her Caribbean home, and Kincaid, a Scottish surname that underscored her colonial heritage. Two names, two histories. Derek Walcott described this dual inheritance as “the monumental groaning and soldering of two great worlds,” which come together like “halves of a fruit seamed by its own bitter juice.” Kincaid—who understands the pleasure of transgression—eats the whole fruit with relish. She hates the English even as she loves Charlotte Brontë, Dickens, and Keats. She loves the small island where she grew up even as she rails against its limits: the cramped horizons, the stifling morality, and the psychic and geographic disfigurements wrought by centuries of slavery.

KINCAID’S PATH TO BECOMING A WRITER—her creation story—is a remarkable one. How does a nurse-in-training from Antigua, who at sixteen begins working for a family in Scarsdale, New York, and sending money home, become, at age twenty-five, a staff writer for The New Yorker? What wild process of self-fashioning must have taken place?

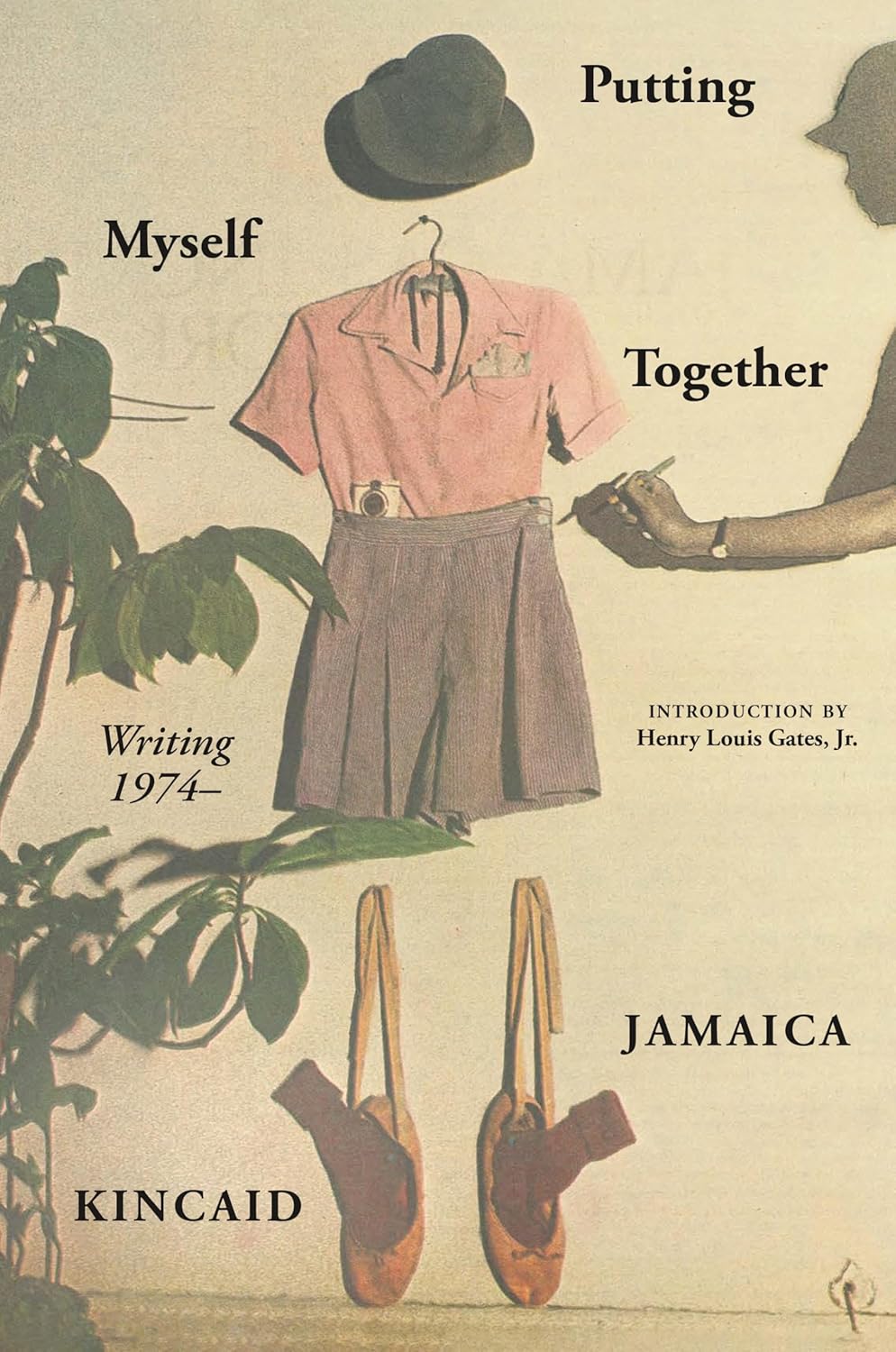

Putting Myself Together, a new volume of essays covering five decades, brings together work left out of her previous collections—writing from Ms. magazine, The Village Voice, and Harper’s—and illuminates the steps by which a young Black woman was able to get a job in the 1970s writing dry Talk of the Town pieces for The New Yorker and then become a celebrated novelist. In a piece that first appeared in Rolling Stone in 1977, Kincaid writes about her time in Scarsdale, not yet seventeen and working as a maid. At some point, she seems to have decided that whatever her future held, nursing would not be part of it: “I couldn’t stand the sight of blood, and when I would see someone ill I would sympathetically develop their symptoms.” The narrator of her novel Lucy has a similar distaste for the path plotted out for her: “A nurse, as far as I could see, was a badly paid person, . . . a person with cold and rough hands, a person who lived alone and ate badly boiled food.” Lucy thinks she would make a better magistrate, “someone who runs things.”

Kincaid and her fictional surrogates bring a delightful disdain to their employment. Lucy is roundly unimpressed by the fragility and obliviousness of Mariah, her wasp housewife employer, and she berates the woman for her ignorance of colonialism. When Mariah tells her, with pride, that she has a little “Indian blood,” Lucy almost brings the forty-year-old woman to tears. She sees in Mariah a wish to enjoy colonial wealth without its moral cost: “How do you get to be the sort of victor who can claim to be the vanquished also?”

In the Rolling Stone essay, Kincaid describes how she began to refashion herself in accordance with these new ambitions. She used a straightening cream on her hair and started wearing bell-bottoms. She bought a succession of unusual hats. Through The New York Times classifieds, she found a job as an au pair for a family based in the city, the screenwriter Alice Arlen and her husband, Michael, a writer. The ad asked for a young woman who could swim and drive; Kincaid could do neither, but she wrangled it. The change of scene proved fruitful: Arlen encouraged Kincaid to enroll at the New School in Manhattan, and Kincaid traded socials at the Young Women’s Christian Association in Yonkers for hanging out in Greenwich Village. Another kind of life began to take shape.

In the mid-1970s Kincaid began writing her first short essays for The Village Voice, a handful of which are collected in Putting Myself Together. Even then her writing was wry, knowing, and audacious. In “The Triumph of Bad and Cool,” from 1974, she attends a live screening in Harlem of the fight in Kinshasa between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman: “Allah now has the oil and a world boxing champion.” Those early pieces display her sardonic insights into the ways African Americans were portrayed in popular culture. In “If Mammies Ruled the World,” Kincaid writes of going to see Gone with the Wind four times. Kincaid is drawn not to Scarlett O’Hara (a “petulant little bitch”) or to Rhett Butler (“dashing chump”) but to Hattie McDaniel, the Mammy who cares for the white characters—“the sort of person to whom you can say, I just raped fourteen children and I killed eight of them, and she’ll say isn’t that terrible, I love you anyway.” Around this time, Kincaid met George W. S. Trow, a young writer at The New Yorker, who took her under his wing and introduced her to William Shawn. At their first meeting, as Kincaid tells it, she ordered the most expensive thing on the menu and then watched, mortified, as Shawn ordered only a bowl of cornflakes. Whatever the impression she made, he offered her a chance to write for the magazine.

Kincaid wrote Talk of the Town dispatches on everything from the West Indian Day Parade to the US bicentennial. She covered with particular élan the city’s thriving disco scene—from basement dance clubs offering bowls of fresh fruit to midday Black discothèques where the “young, upwardly mobile” danced on their lunch breaks. Like many before her, Kincaid chafed at the ironic detachment of the Talk voice—the clipped, impersonal style. Talk Stories (2001), which collected these pieces into one volume, charts her growing disillusionment with the first-person plural, and with the press trips and conference lunches expected of a party reporter. Each year she resolved to write fiction, and each year she didn’t.

Then, in 1978, when she was twenty-nine, someone gave her a copy of Elizabeth Bishop’s Geography III, and a fictional blueprint presented itself. After reading the opening poem, “In the Waiting Room”—told from the perspective of a nervous child waiting for the dentist—Kincaid sat down and wrote her first short story, “Girl.” A single sentence running to six hundred words, it lists the duties of a daughter in staccato rhythm: “this is how to sew on a button; this is how to make a buttonhole for the button you have just sewed on; this is how to hem a dress when you see the hem coming down and so to prevent yourself from looking like the slut I know you are so bent on becoming.” In a conversation with the South African playwright Athol Fugard, which first appeared in Interview magazine in 1990, Kincaid swaps out Bishop for Brontë. Her “moment of discovery,” she acknowledges, was reading Jane Eyre. In both cases, she is drawn in by a disoriented child facing an inexplicable punishment.

The short fictions that followed were published in The New Yorker and later collected in At the Bottom of the River (1983). Incantatory and oneiric, these fragmented stories—each only a few thousand words—are very different from her later style. Children, yes, mothers, yes, but also rivers, trees, ancient cities, and a great, gaping pit. “I shall grow up to be a tall, graceful, and altogether beautiful woman,” says a young narrator in “Wingless,” “and I shall impose on large numbers of people my will and also, for my own amusement, great pain.”

KINCAID IS ONE OF THE GREAT WRITERS OF DAUGHTERHOOD and of the love, sadism, and erotic charge that can persist between a mother and her child. At the center of it all, in nearly every novel, essay, and anecdote, is Annie Drew—her mother, muse, and lifelong antagonist. She taught Kincaid to read at the age of three and a half using a biography of Louis Pasteur; when she felt the child was taking up too much of her time, she sent her off to school with the instruction to tell anyone who asked that she was already five.

In Annie John, Kincaid’s superb novel of childhood, the young narrator follows her mother around like a duckling, finding moments to “sniff at her neck, or behind her ears, or at her hair.” She thinks her mother is so beautiful that her head should be minted on a sixpence. In the early years of their romance, Annie’s mother is a benevolent god, bathing and carrying her, chewing her daughter’s meat before placing it in her mouth. “It was,” Annie says, “in such a paradise that I lived.”

In Kincaid’s work, the great organizing principle is the fall from grace: the author is alienated from language and culture by the “European intrusion,” banished by her mother, and exiled from her Antiguan home. Every sentence is written from these exiles—linguistic, emotional, geographic—and while she does not allow herself to be compromised by nostalgia, she sifts through memories like a hoarder, numbering the injustices that have taken her from a state of innocence to experience.

A perfect love, after all, makes possible an exquisite betrayal. In the personal essays collected in Putting Myself Together, Kincaid’s interpretations of her own childhood offer keys to the structures that define her fiction and wider writing. “I lived in an Eden made up of my mother’s love for me until I was nine years of age,” she writes in the 2009 essay “Lack, Part Two,” “and then was cast out of it by a transgression.” This transgression occurred when she was asked by her mother to babysit her newborn brother, and she promptly dropped the baby on his head. Kincaid denies attempted murder (which, of course, makes you wonder), but the punishment was emphatic. She was shipped off to the island of Dominica to stay with her grandmother and aunt, while her mother—the betrayal!—had another son. Kincaid spent a baleful stint in exile writing vicious little journal entries falsely accusing her aunt of refusing to let her eat or bathe or clean her “private parts.” When the aunt discovered these notes tucked under a stone in the garden—Kincaid insists she did not mean for them to be found—she was sent back on the steamboat to her mother.

Kincaid understands that if the mother is God, then the daughter must choose to be either Jesus or the devil. Though what choice is that, really? Paradise Lost runs like a current through her writing. “I felt like Lucifer,” says Lucy, “doomed to build wrong upon wrong.” Ensconced with her host family in New York, she cuts her mother from her life. Over the course of the book, she receives nineteen letters from the woman, one for each year of her life, and places each one, unopened, on a growing pile. When an envelope arrives with the word urgent written across the front, she considers it and then adds it to the rest. Still, she ruminates: “I could hear her voice, and she spoke to me not in English or the French patois that she sometimes spoke, or in any language that needed help from the tongue; she spoke to me in language anyone female could understand. And I was undeniably that—female. Oh, it was a laugh, for I had spent so much time saying I did not want to be like my mother that I missed the whole story: I was not like my mother—I was my mother.”

Lucy considers singeing the letters at their corners and sending them back unopened like a spurned lover, but she can’t trust herself to go near them: “I knew that if I read only one, I would die from longing for her.” This ambivalence is echoed in the memoir pieces in this collection: “I don’t want to know why I hate my mother so, and why I love her so,” she writes in “Jamaica Kincaid’s New York,” explaining that despite this confusion, or perhaps because of it, she does not intend to see a psychiatrist.

SOME HAVE ACCUSED KINCAID’S WORK of being repetitive. A review of her third novel, The Autobiography of My Mother (1996), called it “the latest and least effective reiteration of the themes of her four earlier books.” And it’s true that Kincaid draws from a limited anecdotal store. Her rare forays beyond childhood experience in fiction—Mr. Potter (2002), an account of an Antiguan taxi driver, and See Now Then (2013), about a family living in Vermont, her current home—have never felt as fully realized. The characters can seem underdeveloped, the narrative muddy or rambling. She has her repertoire, and this new volume can feel, at times, like a reservoir for repeated anecdotes: a Czech doctor who hides his racism behind germophobia; the hated Wordsworth poem about daffodils that she was forced to memorize by her British-run school. That daffodil story crops up a handful of times just in this volume: her anger at reciting a poem about a plant that she had never seen and probably never would: “What was a daffodil, I wanted to know, since such a thing did not grow in the tropics.”

In the hands of a first-rate storyteller, though, a story is never the same in the retelling. Kincaid’s strength is that she allows her stories to change. Not just the shifting of this or that detail, but her own inferences and responses. In the early 1990s, daffodils enraged Kincaid. In 2001, in The New Yorker, she admitted to planting five hundred in Vermont. In 2007, in Architectural Digest, she confesses to fifty-five hundred. A détente develops across the essays: she resents learning the poem, but she forgives the daffodils and Wordsworth, who could not have known how his poem about flowers and clouds would be used. Cézanne painted the Mont Sainte-Victoire a hundred times. Kincaid retells the same stories: prising them open, testing them, searching for what they still hold.

PERSONAL AS THEY ARE, Kincaid’s themes trace a shared Caribbean history of departure and return. Derek Walcott and V. S. Naipaul—two Nobel Laureates of the Caribbean—were literary touchstones as Kincaid came of age, and she sits in an interesting position between them. Naipaul looked back at Trinidad from his home in Wiltshire and saw an island “with no history, in a borrowed culture.” Walcott believed that he was witnessing “the early morning of a culture” from St. Lucia, a literary landscape being written into existence: Jean Rhys’s old Dominica, the Martinique of early Aimé Césaire, and the Guadeloupe of Saint-John Perse. Walcott himself contributed Omeros, a sprawling Homeric epic that attempted to build a literary tradition from colonial detritus.

Though Kincaid aligns herself explicitly with Walcott—her third novel is dedicated to him—she shares more with Naipaul than she might care to admit: like him, she left her island as a teenager; like him, she looks back with frustration at what she sees as the provincialism and corruption of the postcolonial West Indies. In The Middle Passage (1962), Naipaul describes his alienation from an island he sees as “unimportant, uncreative, cynical.” In an interview that appears in this collection, Kincaid bristles at his defection to the other side: “I’m awfully glad he got a knighthood out of it though. . . . Work well done.”

Still, Kincaid is no Homeric idealist. It was twenty years before she returned to Antigua, and when she did the newly independent country was hard to recognize. Kincaid dwells on her complicated relationship with Antigua frequently in this volume, in particular in an excerpt from the 1988 book-length essay A Small Place: “What I see is the millions of people, of whom I am just one, made orphans: no motherland, no fatherland, no gods, no mounds of earth for holy ground, no excess of love . . . and worst and most painful of all, no tongue.”

Kincaid herself insists on speaking what she calls “conventional English” rather than the “broken English” spoken by Antiguans. There is a defiance in her refusal to idealize postcolonial Antigua: it is indebted and corrupt, and still it repeatedly elects the same political dynasty. Yet, unlike Naipaul, she seeks to explain how this orphaned state came to be: the displacement of a people and an imposed model of acquisitive capitalism.

A Small Place, written when she was nearing forty, describes Kincaid’s visit to the old colonial library in St. John’s where she used to read with her mother as a child. She recalls the wide veranda, the big open windows, and the beautiful wooden tables and chairs where people sat like “communicants at an altar.” It was the perfect sanctuary for her and her fellow Antiguans to absorb, again and again, “the fairy tale of how we met you, your right to do the things you did, how beautiful you were, are, and always will be.” Post-independence, the library has been damaged by an earthquake and remains closed. It was in that library that she first read books like Jane Eyre. Kincaid hates the British; Kincaid misses the library. She doesn’t seek to resolve the contradiction: both are true, and it is this lack of resolution that lends so much of her writing its resonance.

Kincaid doesn’t just rage against empire—she points out the weirdness of it. Why were her grandfather, uncle, and brother named after King Alfred? Why was Walcott’s father named after Shakespeare’s home county, Warwick? She looks at a Rembrandt painting and wonders where the Dutch people were getting all that fancy food. She sees “all the horrible things that a civilization requires in order to be a civilization.” It is only at nineteen, living in New York, that Kincaid realizes she has never read a book of serious literature written in the twentieth century or by someone who was not English. You can’t help but be struck by the strangeness—and the success—of the colonial system.

KINCAID HAS MOVED THROUGH DISTINCT PREOCCUPATIONS across the decades. The final third of Putting Myself Together is dedicated to her writing about gardens, much of which appeared in columns for Architectural Digest. It was perhaps inevitable that Kincaid’s interest in planting things and watching them grow, taught to her by her mother, would become entwined with her meditations on empire. Over the years, since she moved from New York to Vermont, she has published several books on modern and historic gardens—My Garden (Book) (1991), Among Flowers (2005), and An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children (2024)—each exploring the relationship between the gardens of England and the garden of Eden (her “favorite garden of all”).

“I was never really making a garden so much as having a conversation,” begins a 2020 Substack essay in which Kincaid reflects on the garden’s origins. If the modern garden represents a turn from agriculture to horticulture, from sustenance to ornamentalism, she argues, then it is a shift made possible by colonial wealth. It is for this reason that she dates the birth of the modern garden to 1492, the year Columbus landed in the Americas. Her cherished garden is a compromised space with “violent implications.”

There is more to her interest than moral disapproval. Her writing reveals a fascination with—and at times an admiration for—the figures she investigates: “Carolus Linnaeus, the great Swedish doctor and botanist and the inventor of the binomial system”; the Founding Father George Washington with his enviable garden at Mount Vernon, built, admittedly, with slaves. In Among Flowers (2005), she recounts a seed-hunting expedition to the Himalayas with a group of plant-hunters, one that bears disconcerting similarity to the colonial ventures she elsewhere deplores. She bristles with excitement at the idea of collecting and cataloguing rare seeds, almost as if she needs to prove that understanding the mechanisms of domination does not exempt one from their allure. The garden becomes a space where she can stage her own complicity in the desire to possess and to dominate.

Until now, these connections have mostly remained implicit. But in the final essay of the collection, “The Disturbances of the Garden,” Kincaid drives deeper, even as she acknowledges that the web of associations is eluding her control: “I am meaning to show how I came to seek the garden in corners of the world far away from where I make one, and I have got lost in thickets of words.” I hope that Kincaid will write more on this complicated pleasure: the intimate dominion of the gardener in her garden. It is her willingness to sit with what Walcott called her “own contradiction” that gives her writing its uncanny power. Kincaid remains the eternal daughter—pointing out with a wide-eyed and deceptive innocence the hypocrisies and paradoxes others would not dare to voice. “I hope I don’t spend my whole life saying ‘when I was little,’” she wrote when she was twenty-eight, “even if it turns out to be the most interesting thing to happen to me.” In a way, that’s exactly what she’s done—and the work is all the richer for it.

Josie Mitchell is an editor at Granta magazine.