WHEN LEIF RANDT’S novel Schimmernder Dunst über Coby County came out in 2011, it was unique in the German literary world. Randt was one of the few German authors writing what is now commonly called speculative fiction—not hard sci-fi but not realism, either—and in Berlin, where I lived at the time, it generated enough buzz thatI was willing to read it in German. I loved it. The book’s titular Coby County is a coastal resort community for an aging creative class, sponsored by a cosmetics company, where everyone is healthy and wealthy and race-blind and alarmingly content with their branded lives. But beneath the “shimmering haze” of the neoliberal fantasy lies . . . something sinister. It’s hard to say what’s wrong, but it’s just too uncannily nicethere, and the satire is too funny to take at face value. In Randt’s next novel, Planet Magnon (2015), a kind of twee space opera, it’s more obvious what the pitfall of the intergalactic AI-driven society might be: the repression of unhappy, imperfect people.

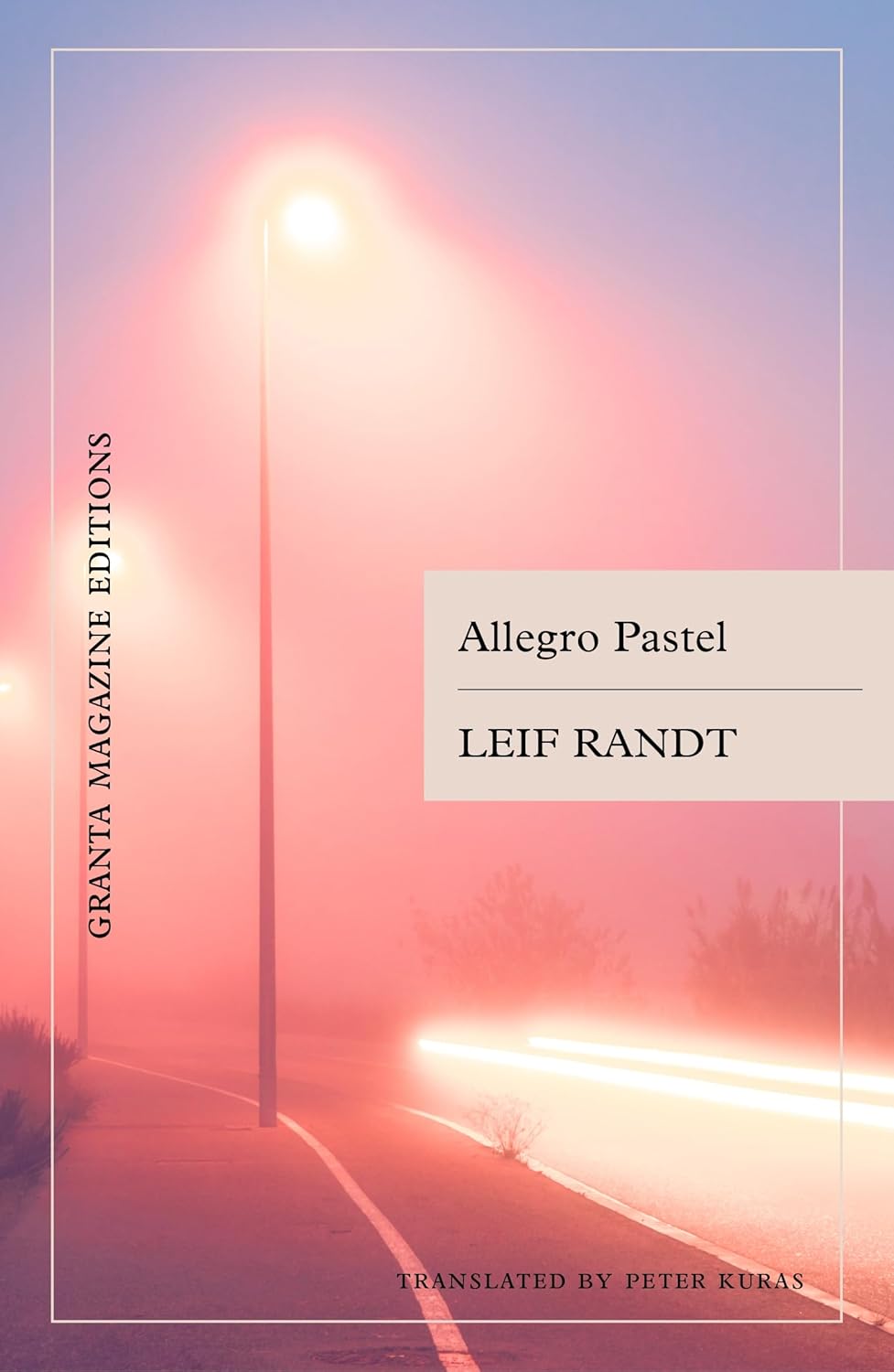

But after reading Randt’s realist novel Allegro Pastel, which came out in 2020 and was published in Peter Kuras’s excellent English translation this year, I wondered whether the earlier novels were giving me dystopia simply because I assume that a speculative utopia is never what it seems. Genre conventions imply that perfection—homogeneity—is a dangerous illusion or a facade that has to crack. Now, I wonder whether Randt’s imagined worlds were meant less as cautionary utopias thanearnest, aspirational ones. Maybe Coby County wasn’t supposed to seem like a warning but like a nice place to live. As one reviewer of that book remarked: if you cut away the surreal elements, the novel’s setting would resemble the pleasant Berlin neighborhood of Prenzlauer Berg. And that’s more or less the world of Allegro Pastel.

Set in 2018-19 Germany, the novel is a breezy millennial love story. Jerome, thirty-five, designs websites for artists and cultural institutions. Tanja, twenty-nine, is an author whose speculative novel about VR, PanoptikumNeu, won her fast fame. They meet at the launch of the web series based on her book and quickly fall in love. She lives in Berlin; he lives in the town near Frankfurt where he grew up, and between visits their relationship progresses through texts and emails in a Sally Rooney–esque epistolary mode. They talk about their families and friends, drugs and parties, web design and writing habits. Their observations are superficial in every sense—fixated on appearances, emotionally untroubled, and unburdened by irony.

The couple is drawn together by their shared sense of well-being and satisfaction. Early in their relationship, Jerome sends Tanja a selfie captioned: “300% Joy.” For the duration of the book, even at his lowest points, Jerome’s joy barometer probably doesn’t dip below 70 percent. He likes his work. He likes the way he looks. He likes the place he lives. Upon being given a coupon for a rental car rebate, he is “almost embarrassed by how happy” it makes him. Tanja had a happy, normal childhood. She is “a fan of herself.” Her emotional landscape is a bit rockier than Jerome’s, but largely uninflected with major-chord feelings like guilt or rage or jealousy. “Tanja had always been put off by people who thought about their emotions all the time,” Randt writes. “At the end of the day, she usually felt good; she invented characters, and she rarely suffered. Maybe she had fallen in love with Jerome because he, too, rarely suffered.”

Much character development happens through brand curation: Tanja has a “passionate relationship” with the sports store Decathlon, where she buys “tops from Kalenji, shorts from Domyos, hiking shoes from Quechua, and badminton shoes from Artengo.” Jerome orders a Dior backpack online. “It’s almost certainly a dupe, but it’s super-nice! 👻👻.” Tanja “a hundred percent” shares his enthusiasm for “a well-duped luxury product.” It’s just one of the many ways the two are nicely matched. Their lives, and the story, slip amiably by, weightless and frictionless. Can it really be so simple—just two calm and well-adjusted people partying and purchasing products?

Sometimes, all this happiness measured in units and percentages sounds like anhedonia. Perhaps they’re mistaking the absence of pain for the presence of pleasure. Tanja and Jerome prefer drinking green tea at exactly 70 degrees Celsius. Their sex is good. They like checking and discussing the weather. Tanja is “rarely enraptured by works of visual art or by performances, and never by literature.” (This doesn’t worry her because she’s certain that she will one day make a “truly successful artefact”—her intense arrogance is what gives her an edge over Jerome as the more compelling character.) At other times, their contentment strains credulity—when, for instance, Tanja relishes the food served on a great Ryanair flight, or when Jerome rawdogs a train ride “in the best of moods” because he has long enjoyed “a very good relationship with the Deutsche Bahn.” (This will sound like hardcore fantasy fiction to anyone who regularly rides the Deutsche Bahn.)

At one point, Jerome fantasizes about finding a “physically demanding side job” for variety, but he doesn’t need one; he can earn a year’s salary in one quarter. Tanja’s book earnings pay for her apartment, her badminton gear, and plenty of ketamine. Taking drugs is what allows them to reach new heights of emotion and connection. After a euphoric club night on MDMA, Tanja muses in a message to Jerome that drug comedowns are what allow “naturally up types like us” to experience “empathy and solidarity,” because it’s the only time they catch a glimpse of despair. She is referring to solidarity with her clinically depressed sister, whose gloom frustrates her, not solidarity with, say, those of another social class.

Jerome believes it is wrong to “suffer on behalf of others” or to “assume” that other people are unhappy, even if they look sad. When he was younger, he often imagined himself in other people’s positions, but ultimately found it too “draining” an exercise. Now, in his thirties, he finds the traditional concept of empathy—trying to imagine how another person feels based on the available evidence—a wrong and unfair invasion. Instead, he prefers a personal brand of empathy where he stays “aloof” and unaffected by what he sees. Strange, in a world where superficiality reigns, to construct a system of ethics that requires you to ignore the surfaces of other people’s faces.

DURING ONE OF Jerome’s visits to Berlin, Tanja becomes abruptly “annoyed” by his presence. It’s “like a kind of blackout,” to the point that she physically recoils. He leaves and a period of estrangement ensues. Tanja starts sleeping with her best friend’s crush in an act of double betrayal. Jerome finds someone to sleep with, too. But he and Tanja miss each other. Tanja wonders whether she can recycle this longing into her writing: “The irreplaceability of Jerome Daimler felt, during the best moments, like a caesura she could put to aesthetic use. At many other times, Tanja found it sad.”

Tanja doesn’t know why she breaks up with Jerome, or why she fucks the guy her friend likes. I also don’t know, but I can make some guesses—anyway, sometimes the most believable characters behave in mysterious ways. Yet Randt is unusually insistent on rendering characters devoid of self-insight or psychoanalytic depth, leaving a lot up to the reader. Where Rooney might let her characters debate Marxism or fight, Randt keeps Tanja and Jerome musing rather than agonizing, remaining consistently upbeat. Even a Tao Lin character would show signs of disaffection.

Tanja is given a classic reason for avoiding self-analysis: her mother is a therapist. Jerome’s disinterest in plumbing his own depths is less explicable. We get lines like: “Jerome could link most of his personal characteristics to his upbringing—as a child he’d liked to line his toys up in rows on the carpet—but generally he was not a fan of classical psychology.” Or, “He liked playfully distinguishing between an inner personality, one that only he knew, and an outer personality, composed of things attributed to him by his environment.” His inner personality “reminded him of the text-to-speech function on his laptop.”

Creepy, no? Is this disinterest, or is it incapacity? Does Jerome possess a preconscious bicameral mind? Is he repressing something awful? Is Jerome a holy fool? Is the book a radical genre experiment after all? Why can’t I just let him be happy?

ABOUT A THIRD of the way through the novel, I was immersed in the book and gliding along, feeling vaguely jealous of Jerome and Tanja’s nice, secure lives. Then I dropped the book in my lap.

It was not a dramatic plot point that jolted me out of my reverie. It was a brief, one-page scene in which Tanja and Jerome end up at a Berlin bar and have a seemingly pointless chat about politics. Their friend mentions that this bar is associated with the “Antideutsch tradition.” What is Antideutsch, asks Jerome? He thinks it might be like Antifa, as in antifascism. No, Tanja explains: they are a group that stands “against the state and for Israel. They’re communists but not anti-capitalists, because they think that anti-capitalism is always antisemitic. You could say they’re obsessed with history. They’re of the opinion that given the Second World War there really shouldn’t be a Germany.” Then we get a brief exposition of Tanja’s political commitments (nil) and Jerome’s discomfort with labels and petitions. Their friend says the Antideutsch are “just confused.” End scene.

If Tanja’s description of the Antideutsch sounds confusing, that’s not because she’s wrong. The “anti-German” fringe grew out of 1980s and ’90s leftist circles who opposed post-wall reunification, believing nationalism would inevitably lead to fascism again. By the 2000s they were primarily united by vocal support for Israel, according to the thesis that German nationalism can only be countered by its supposed perfect antidote, Zionism. This tactic involves rushing headlong toward the dreaded outcome one purports to oppose—fascism—and the Antideutsch fringe has only helped to create the conditions for the rise of a new German nationalist party.

The characters’ response to this topic conveys a different order of indifference than all the other things they don’t care about. Hitting this scene in the book, the allegro tempo brieflyslows, and the pastel hues darken. It’s like suddenly coming across a disturbing image in the doomscroll, a moment of friction in an experience meant to be frictionless. The fantasy world shows its construction materials, and you realize the extent of Randt’s expert world-building. This is a world that props up the happiness of exactly Tanja and Jerome. To answer my earlier question: it’s hard to just let Jerome be happy because his happiness is predicated on willful ignorance—of himself and the world. For Tanja the situation is even more damning. She’s not ignorant, she’s just not interested.

WHEN TANJA SAYS THAT the Antideutsch are “obsessed with history,” she means this as an insult. Her and Jerome’s model of history and the psyche is that it is possible to exist in the here and now, unhaunted by personal or historical events. If you’re seeking Trauma, that’s just the name of a bar where Tanja goes for a concert.

In the second half of the book, Jerome and Tanja start messaging again. “I couldn’t tell from your voicemail that you’d repeated it so often,” writes Tanja after listening to a recording that Jerome confessed he’d rehearsed several times. “It sounded real. I was touched.” They test a reunion by doing drugs together at a wedding, but the relationship unravels a second time. At the end, Jerome finds he’s gotten his new girlfriend, Marlene, pregnant. Marlene, he reasons, is a good option because she has a stable income and stable emotions. He makes a PowerPoint with pros and cons, via which the two decide to keep the baby. In her last email volley to Jerome, Tanja writes: “What would have been more common than for a narcissistic web designer to stay childless for life? It feels almost subversive to me that you’re becoming a father.” The idea that Jerome could act subversively is, of course, laughable. If he could, Tanja would not be able to predict with such certainty that when she visits Jerome’s family in the future, “You’ll be happy.”

Allegro Pastel opens with a quote from the self-help guru Eckhart Tolle about the illusory nature of pain. Jerome in particular subscribes to this view, cultivating a vague spirituality through mindfulness. When his breakup is still fresh: “Under no circumstances did he want to deal with the past or the future. . . . But the present, which consisted of enormous light, professional success, and astonishing doses of euphoria while jogging, was pretty much all right.” Randt is adroit at creating a sense of immediacy and presence—of nowness. For the most part, the book feels like it moves at the speed of life, which is possible because it stays in the shallows rather than getting tugged down into the depths.

In a conversation with the Swiss magazine Republik, Randt describes the period in his life when he wrote Allegro Pastel: “Overall, it was a wonderful time. A privileged, luxurious, beautiful life.” Aware that this state was fleeting, he wanted to capture the good mood in the moment. When the interviewer asks the predictable question about why the characters don’t ever reflect on “sexism, racism, social inequality,” et cetera, Randt replies that these issues simply “don’t affect their everyday lives,” and “it would have been dishonest to let them get worked up about world politics to show that they were on the right side.” They’re “too narcissistic to want to take an ideological position”—the obvious counterpoint being that never choosing a standpoint is an ideological position. Of course it is an “insane privilege,” Randt says, to live inside “such a cocoon.”

I’m not upset by characters with “bad” politics. I refuse to willfully misunderstand millennial novelists’ selfish, apolitical characters as endorsements rather than retweets. Tanja, who can be read as a proxy for the author, encounters readers like that, who demand to know about “the realness of her characters” and the realness of her views. Tanja replies honestly: “I always write what I really think.” As far as I can tell, Randt also writes what he really thinks, without irony or disingenuousness, and it’s similar to what Tanja thinks.

In Germany, Randt is often contextualized within the Popliteratur canon, as a descendant of authors like Rainald Goetz and Christian Kracht known for their preoccupation with consumerism, mediatized life, the clash of high and low culture, and the emergence of counterculture. Randt is certainly indebted to and as skilled as these authors, but the generational difference is marked: when Allegro Pastel came out in German, the reviewer Jens-Christian Rabe argued that Randt is unlike his forebears because of his characters’ total lack of “defiance.” They’ve got nothing to risk and nothing to resist—in the past or in the future. There’s an extreme historical specificity to Randt’s framing of historylessness, safety, and neutrality as the conditions for happiness. As he puts it: “Allegro Pastel feelings are probably limited to the late 2010s.”

Of Jerome and Tanja’s perpetual contentment, Randt says: “I can understand why people find the characters’ thoughts bizarre, but they are not unrealistic.” I agree that their thoughts are realistic, which is exactly why they’re sometimes disturbing, but a purely utopian realism is a contradiction in terms. Realism gestures outward, toward the mess and contingency of life, while utopia is necessarily sealed off, a tightly controlled projection of desire—a cocoon. Randt is writing realism, but his German utopia is not real; he’s built it artfully and expertly, just like he built the fantasy universe of Planet Magnon. Realism is not made of reality—it’s a literary construction and convention like any other genre, requiring world-building to make it feel plausible, and usually revealing authorial intent through what it chooses to portray and exclude. Tanja and Jerome may live in a utopia, but that’s not the end of the sentence. It’s a utopia, for them. And you too can live there for the duration of 288 pages.

Elvia Wilk is a writer in New York. Her third book will be out in 2026.