IT’S LATE AUGUST AND I’M WALKING THROUGH THE PASSAGE DES PANORAMAS, the oldest covered arcade in Paris, simply because Lucien Chardon passes through it with Étienne Lousteau in Honoré de Balzac’s Lost Illusions, the best novel ever written, which I finished shortly before arriving in the city. I’m carrying a copy of Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes (vulgarly retitled Lost Souls in Raymond MacKenzie’s mostly excellent translation), which continues Lucien’s tragic story.

I was in Paris a few months ago, too, in the late spring. One afternoon, walking back from the Jardin du Luxembourg, I happened upon the Place de la Sorbonne, one of Paris’s myriad pleasantly timeless little squares. I sat for a bit by the fountain, reading around in A Walk Through Paris: A Radical Exploration,by the late publisher Éric Hazan. This book, like his The Invention of Paris, is an anti-guidebook, the opposite of a Rick Steves highlights tour (though I packed Steves, too—he knows where the toilets are). Here, Hazan will tell you, “Dr Guillotin perfected his celebrated machine in the workshop of a carpenter, and is said to have experimented with it on sheep.” Baudelaire was born on this street, I saw Sartre on this one, Victor Hugo hated that statue, Balzac used to live over there.

Reading Hazan—walking through Paris with him—I kept encountering Balzac (often mispronounced by Americans in the manner of Mona, the precocious friend of Nabokov’s Lolita: “Do tell me about Ball Zack, sir. Is he really that good?”). Hazan cites eleven of Balzac’s works in A Walk (Verso’s index attributes authorship of Lost Illusions to one of its characters) and at least twenty-one of them (I lost count, and the index is incomplete) in The Invention. And then there’s Balzac’s Paris, which is what it sounds like. At the time of this first trip, I’d read only Père Goriot, but clearly Hazan and Paris were telling me to read more Balzac (whose corpus, known as La Comédie humaine, encompasses ninety-one interlinked novels and stories, so, whoever you are, there’s always more Balzac to read).

When I got back to the States, I picked up Lost Illusions. Lucien Chardon, poet manqué from the sticks, arrives in the big city with big dreams of literary glory. Of course he finds that in Paris ambitious young writers are a dime a hemistich. Soon he is reduced to eating at a cheap restaurant in the Latin Quarter called Flicoteaux, a “temple of hunger and poverty” that has “played foster-father to many a genius,” “located right on the Place de la Sorbonne”—the very square where I had sat and read about Balzac. I had been just a few feet from the former location of this nineteenth-century sanctuary, which, the internet informed me, Balzac himself used to frequent. A sign! Or a completely mundane coincidence.

Not that anyone needs an excuse to go to Paris, but I began to formulate a plan. My previous trip had been somewhat underwhelming, as I’d made the rookie mistake of flying on Icelandair, whose business model involves making it as unpleasant as possible for you to not get where you’re going. At one point during what was supposed to be a simple flight to Paris with a brief stopover in Reykjavik, I found myself in Finland. I’d never particularly wanted to go to Helsinki, but they do have a cute airport. Just before takeoff the Finnish pilot came on the intercom to say, in English, “The mechanics are becoming ready with their technical actions,” which caused the flight attendant to chastise me as I jumped up to retrieve my notebook from the overhead compartment to write this sentence down. I arrived at Charles de Gaulle eight hours late.

So I decided to return to Paris, with more Balzac under my hat, on a little pilgrimage to Balzacian sites. It meant that I would miss the first department meeting of the fall semester, but I reasoned that being in Paris is better than being in a department meeting.

Thus my presence in the Passage des Panoramas on this beautiful day (I’m actually typing this in New Jersey in November from unorganized notes scribbled in Paris, e.g., “driver keeps playing same Phil Collins song”; “did Balzac have a cat”). But I realize that I feel no particular connection to Balzac here—less even than I felt to Jim Morrison as I stood at his corny grave in Père Lachaise yesterday. Hazan notes “the Panoramas is the passage most frequently encountered in The Human Comedy,” but the passages were “ordinary ways” for Balzac. “Whatever devotees of Walter Benjamin may say, these Parisian arcades were no more important to Balzac than any other street” (guilty). The first time I saw the Eiffel Tower, I remembered a line from the trailer for the Barbra Streisand movie The Guilt Trip, which I haven’t seen. Streisand and Seth Rogen stand before the Grand Canyon, and she says, “How long are we supposed to look at it?” He shrugs: “Ten minutes?” (I assume this is a callback to a similar scene in National Lampoon’s Vacation.) It’s like that for me again in the Panoramas, gazing upon the old gilding and the new eateries.

I decide to abandon my Balzac pilgrimage, having got no further than the first stop. Paris isn’t a museum, though plenty of tourists treat it as one. Hasn’t Balzac, not to mention Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin, told us how to see Paris? “Ah! To wander over Paris! What an adorable and delightful existence that is! Flânerie is a science; it is the gastronomy of the eye. To take a walk is to vegetate; flânerie is life.”

BALZAC’S TWO GRAND SUBJECTS are Paris and money, and everything in La Comédie humaine conspires to reveal the lethality of the former without the latter. For Balzac the city was a battlefield, not just alive but life itself. “For isn’t Paris, after all,” he asks in the opening paragraph of The Girl with the Golden Eyes:

a vast field continually awash in a tempest of conflicting interests raging above a crop of men cut down by death more often than elsewhere, always reborn equally harried, exuding through all the pores of their contorted, twisted faces the wit, the desires, the poisons that fill their minds?

Later in this novella he calls Paris “a hell.” Elsewhere in his work, “Paris is a daughter, a friend, a wife, whose physiognomy always delights me because it is always new to me. I study her at all hours and each time I discover new beauties.” Hazan brings these passages together, but one could choose a hundred different contrasting views of the city from Balzac’s work that would serve the same purpose. Paris is a paradise, an inferno, a delight and a cesspool, because it is everything: “Paris is always that monstrous marvel, that amazing assemblage of activities, of schemes, of thoughts; the city of a hundred thousand tales, the head of the universe.”

“Paris is a strange world,” says Lucien in Lost Illusions, and, later, “Paris is a bizarre abyss.” “What a strange place Paris is!” says a character in Splendeurs et misères.MacKenzie says that “Balzac in his fiction was using Paris as a symbol, no matter how he wished to appear o be a mere documentarian”; and Robert Alter writes of “Balzac’s project of mythologizing Paris.”

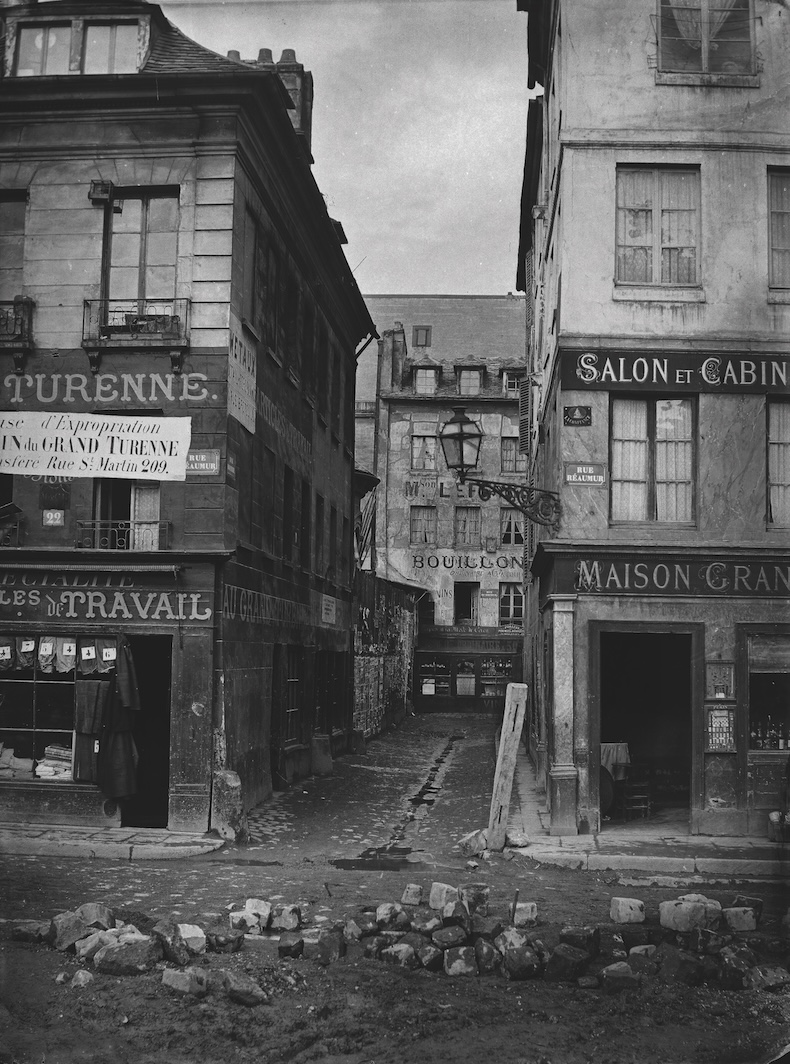

I don’t think this is quite right. It’s not that Paris is a myth or symbol for Balzac, but that Paris is myth and symbol in itself—a myth about itself, a symbol of, well, everything. “When you come right down to it,” someone says in Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch,“Paris is one big metaphor.” Balzac understood this. Paris is never exactly identical with itself, never quite in sync. It is always overlaid by visions of previous Parises read about or seen in paintings, photographs, and films (and social media feeds). Already in 1857 Baudelaire lamented that “Old Paris is no more.” He was thinking mainly of Haussmannization, that too allegorical destruction-as-rebirth in the name of industry and progress. Balzac did not live to see the broad boulevards and cream-colored, mansard-roofed apartment buildings that signify “Paris” to us. The dominant element of the city for him was mud. The opening of Père Goriot hymns “that illustrious valley of flaking plasterwork and gutters black with mud, a valley full of suffering that is real, and of joy that is often false, where life is so hectic that it takes something quite extraordinary to produce feelings that last.” This could be inserted into the first paragraph of Dickens’s Bleak House without disruption. Hazan goes on about mud in Balzac, citing several works, for four pages, wryly noting that “Paris, a city of mud . . . was not a new observation.”

But if the mud remained, the face of Paris did change in Balzac’s time, as Hazan notes. Even before Haussmann—the villain of Hazan’s books—destroyed so much of the quarters romanticized by Baudelaire, Paris was already a city in motion. In Lost Illusions, Balzac’s narrator laments the disappearance of the Galeries de Bois, or Wooden Galleries, a congeries of booths and vendors’ stalls, “small huts made of boards, with shabby roofs, set in a dim light that entered from little apertures on the court and garden sides,” in which mingled the contents of the head of the universe. Set in what is now the Palais Royal, the “obscene booths” of the Galeries were “abuzz with chatter and a mad gaiety . . . from the Revolution of 1789 to the Revolution of 1830.” Booksellers, ventriloquists, charlatans, milliners, the fashionable and the destitute, puppet shows, chess-playing automatons, fruit and flower vendors, tailors—but “only at nightfall did the real poetry of this terrible place come to life,” as prostitutes “from every corner of Paris” flocked to the stalls. The “frightening rapidity” with which Paris altered her appearance lifted Balzac to his most elegiac heights: “Immense, unanimous regret accompanied the fall of these marvelous wooden structures.” Soon, he mourns elsewhere, “old Paris will exist only in the works of novelists brave enough to describe faithfully the last vestiges of the architecture of our fathers.”

And though one can still see something of this old Paris in the photographs of Eugène Atget and Charles Marville, or read of it in Hugo and Flaubert, it’s Balzac who brings the vanished city most vividly to life, because he is to Paris what Dickens is to London, what no single writer is to New York: its anatomist. One need not have visited Paris to appreciate Balzac, of course, but I’m not sure if the opposite is true. Paris can seem realer in Balzac’s pages than in “real life,” which itself seems more and more indistinguishable from fantasy.

THE KNOCKS ON BALZAC ARE ENDLESSLY REHEARSED. He wasn’t much of a stylist, and it’s true he was no Flaubert (who wrote five novels). For that matter, I have yet to come across any three paragraphs of Balzac that contain as much poetry as those that open Bleak House.He will erupt into didactic tangents, fulminating against bourgeois architecture or “the dishonesty of the lower classes in Paris.” His readers find themselves “occasionally regretting,” as Chantal Chawaf writes, “a certain residual misogyny, racism and anti-Semitism.” And he was a self-described reactionary monarchist (whom “Marxists could love,” as at least two articles put it).

But what is left over after his defects are enumerated is life.A ruthless capaciousness. He was not a “documentarian” (though, pace MacKenzie, there’s nothing “mere” about documentary, which is a question above all of selection—cf. Atget or Marville), much less the “naturalist” imagined by Zola. The plots are the stuff of melodrama: fatal love affairs, schemers hoist with their own petards, high society, filthy gutters, backstabbers and sycophants, princesses and prostitutes, murder and suicide. He has the forward momentum of the potboiler, the airport novel. But this is all to the good. His is the realism of what Blake called the Human Heart.

Many novelists have seen how insipid and hypocritical people at every social level are, and how they still, despite themselves, manage on occasion to act heroically. But I don’t believe in Emma Bovary or Fabrizio del Dongo as I believe in Lucien Chardon and Lisbeth Fischer. They can seem, if I’m feeling romantic, like people I used to know, even as they are entangled in absurdly implausible machinations. I understand why Oscar Wilde called Lucien’s suicide “one of the greatest tragedies of my life.”

And it’s the characters who commit the worst crimes, who are most clearly at odds with Balzac’s own morality, who are the most richly drawn, the most sympathetic. This isn’t unusual, of course: who finds Alyosha Karamazov more engaging than Ivan, Thomasin Yeobright than Eustacia Vye, Milly Theale than Kate Croy? But Balzac goes to eleven. With maybe two and a half exceptions, every character in Cousin Bette is utterly vile, but most of them offend none but the virtuous. “The pleasures of satisfied hatred,” the narrator muses, “are the keenest and the most ardent that the heart can experience.” In part his novels’ sympathy for such characters depends upon what Marx called Balzac’s “profound grasp of real conditions.” Whatever his dumb views of the aristocracy, Balzac was too good a writer not to see that people end up in poverty and vice through no fault of their own, but “under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past,” as that famous reader of Balzac put it. At the end of Lost Illusions the great villain Jacques Collin (aka Vautrin, aka the Abbé Carlos Herrera, aka Death-dodger) tells Lucien that the law exists simply to uphold “the barrier between the rich and the poor, and if that barrier were ever torn down, it would mean the end of the social order.” Amen.

It is impossible to imagine Baudelaire, Proust, even Manet without Balzac’s example, while his lurid depictions of the dens and disguises of the Parisian criminal underworld made possible the serials of Louis Feuillade. The Human Comedy both stages and draws back the curtain on “this theatrical production called society” (as Jacques Collin has it).

ALL THIS IS FAIRLY STANDARD. But what I take most from Balzac’s enormous tapestry is Paris. Not, I realize in the Panoramas, as an itinerary of particular locations, but as a lived reality, where “everything smokes, everything burns, everything shimmers, everything boils, everything flames, evaporates, gutters, rekindles, glitters, fizzles, and consumes itself” (take that, Flaubert). In Balzac the city is a character. As Hazan puts it: “The Balzacian street is different: the places where the characters live and evolve are part of their personality; they define them in the same way as their physique, their dress or their psychology.” Hazan notes that “only rarely does Proust cite the name of a Paris street, or precisely localize an encounter or event.” Proust knew The Human Comedy as well as anyone, but In Search of Lost Time “has very little to say about Paris.”

I was first awakened in my youth to the idea of Paris by Walter Benjamin and Jean-Luc Godard. But I had a vague sense of it as an expensive, overrated tourist trap, rather like the imbecile quoted in a recent article on theme parks, who explained his preference for Epic Universe’s Harry Potter–themedParis replica thus: “Obviously, if you go to Paris, you’re going to see Paris as it really is”—i.e., dirty, no wizards.

Granted, Paris is also an expensive, overrated tourist trap. The first time I stood with the herd of phones before the barricaded bulletproof glass behind which, in the distance, if you squint, you can just make out the contours of the Mona Lisa, I felt like a rube. But there are three other Leonardos on the wall opposite, crowd-free. And Baudelaire was already complaining in 1860, in “The Painter of Modern Life,” about

people who go to the Louvre, walk quickly past a large number of most interesting though secondary pictures, without throwing them so much as a look, and plant themselves, as though in a trance, in front of a Titian or a Raphael, one of those which the engraver’s art has particularly popularized.

Old Paris has always been no more, and there is never a better time to see the city than right now, whenever that is. T. J. Clark, describing Paris as Benjamin knew it a hundred years ago, says, “Paris was up-to-date and old-fashioned, with the two conditions coexisting street by street or shop by shop: you could take a detour through the 1860s each morning on your way to work.” And so it is today. I imagine Balzac would have hated the Eiffel Tower, but he would have seen it, and described it better than anyone else, after his cranky fashion.

So, coming out of the Panoramas, I resolve to stroll aimlessly around Paris, the birthplace of flânerie. Still feeling a little false, as if I’m following a pretentious script, I walk at random for twelve miles, I mean nineteen kilometers, looping, wandering in and out of shops, sitting in little squares for a while, following the Seine, dead-ending in les impasses, getting lost. Toward dusk I find myself on a bench in a tiny park, not a famous one, a bit scrubby, where as far as I can tell I’m the only non-Parisian. Some boisterous men are playing what I assume is pétanque, a game I don’t understand. And this is Paris, not more authentic than the Louvre and the Eiffel Tower and Notre-Dame, just easier to miss. This is the sort of place Balzac noticed. And I remember a passage from Stefan Zweig’s unfinished biography of Balzac, quoted by MacKenzie in his introduction to Splendeurs et misères: Balzac’s “great secret” was that “everything was raw material,” with “no distinction between high and low.” “One could choose everything,” Zweig wrote, “one had to choose everything.”

Michael Robbins is an associate professor of English at Montclair State University. His books include the poetry collection Walkman (Penguin, 2021) and the essay collection Equipment for Living: On Poetry and Pop Music (Simon & Schuster, 2018).