IN 1999, AT THE AGE OF FORTY-THREE, ANTHONY BOURDAIN had all but given up hope that he would ever be recognized as a major talent in anything. For the man who would soon become famous for courting extremes, this mediocrity was a kind of torture. After a promising start at the Culinary Institute of America, he had been working in kitchens of low-to-middling repute for two decades. As a chef, he was merely competent, having spent his early years chasing good money and hard drugs instead of working his way up in high-end kitchens. Still, he was perpetually in debt, getting by largely because he lived in a rent-stabilized apartment on the Upper West Side with the woman he had loved since high school, who kept them out of housing court by flexing the legal knowledge she had absorbed from watching Court TV. Throughout the 1980s, both were heavy heroin users. They had survived low lows (Bourdain selling his record collection on the street) and gotten clean, and now, every year or so, they went to the Caribbean for a Margaritaville vacation. But Bourdain had always thought he would amount to more. In the early ’90s, thanks to a “freakishly lucky break” courtesy of a college friend, Bourdain got a book deal. But his two novels—a murder mystery about an Italian restaurant run by the mob and a crime thriller set in the Caribbean about married expat-assassins—were, in his own words, “spectacularly unsuccessful.”

He turned to nonfiction. Shortly after finishing his second novel, he banged out an essay about the restaurant business that he’d been mulling over for years. It was promptly accepted for publication by the alternative weekly New York Press, but after months went by without it being printed, Bourdain’s literary agent sent it to The New Yorker. Ultimate credit is due to a different agent: David Remnick remembers receiving the submission care of Bourdain’s mother, a copy editor at The New York Times. “Don’t Eat Before Reading This” introduced the public to some of the unsavory things that probably happened to their food behind the swinging doors of the restaurant kitchen—the contents of bread baskets being recycled, the truth about brunch, and, most famously, reasons not to order fish on Mondays. After the essay ran in an April 1999 issue of The New Yorker, TV crews and vans mobbed Les Halles, the Upper East Side brasserie where Bourdain was the chef, wanting to hear it from the source. “I was in a cranky mood after my last restaurant closed,” he told CBS, looking pleased and suave in a turtleneck and leather blazer, “and felt no reason not to tell the truth about a business I both love and have mixed emotions about.”

He elaborated on his initiation into the life in Kitchen Confidential, which was published just over a year later, was an instant bestseller, and was soon adapted into a short-lived TV show starring a virtually unknown Bradley Cooper as “Jack Bourdain,” a character with whom I, at age ten, was briefly in love. Bourdain wrote about his first oyster, the Provincetown cooks he wanted to join the ranks of because they dressed like pirates and drank a lot, and the series of choices that earned him a reputation as a kind of hired gun in the kitchen, known more for getting the job done than for doing anything truly inspired. Whether the book reads like recruitment material or cautionary tale will depend on each reader’s sensitivity to hedonism in general and the allure of big knives in particular. To Bourdain, the kitchen was a secret society with its own codes and customs and language. He was attracted to the orderliness of its hierarchy and how it was enforced by a shared reverence for shit-talking and hazing rituals. He acknowledged that this was not the only way a kitchen could be run (some chefs, he knew, fostered a calm atmosphere), but that didn’t stop him from celebrating the system he came up in. “I was not—and am not—an advocate for change in the restaurant business,” he later wrote. He liked the status quo because he was part of it, and claimed he wrote Kitchen Confidential with the simple hope that other professional cooks would recognize themselves in it and feel redeemed. Many did.

By the time I first read it, the book had long since become a loaded signifier for douchey kitchen culture. It was the book that had launched a thousand white boy motorbike tours of Vietnam, written for guys who own plating spoons and were taken in by Bourdain’s description of the kitchen as a place where misfits could fit in, where subculture was the culture. Bourdain’s own take on his midlife-crisis book changed as his lot in life improved. In a preface written for an updated edition, he doubles down, defensively: “You will notice that the tone of the book is blustery, that there is rather more than a little testosterone on the page and that I make the occasional sweeping generalization. This was entirely intentional.” But in a 2010 essay, he gets exculpatory, explaining that he was fueled in those dark days by “an unfocused, aim-in-a-general-direction-and-fire kind of a rage.” Rage that he had never had health insurance or owned a car (or thought he ever would), and at himself “for being forty-four years old and still one phone call, one paycheck, away from eviction. For fucking up, pissing away, sabotaging my life in every possible way.”

Bourdain’s reward for his account of grunt work and bad behavior was the ability to leave such things behind. Famously opinionated, a self-proclaimed “obnoxious, lifelong show-off, always eager to shock,” with no patience for sacred cows (he once called Alice Waters “Pol Pot in a muumuu”), Bourdain seems to have enjoyed taking stances more than sticking to them. Upon meeting celebrity chefs he had previously had only harsh words for, he tended to decide that, actually, there was a lot to like about them. He softened in part because he too had sold out (see “Selling Out,” the first essay in his 2010 book, Medium Raw) when he agreed to film a tie-in series to what would become his second memoir, A Cook’s Tour, in which he traveled the world “in search of a perfect meal.”

A Cook’s Tour the show was selfish and inexhaustive by design. There were no must-sees, only what Bourdain wanted to see. He maintained a crazy amount of creative freedom for network TV as A Cook’s Tour became No Reservations became Parts Unknown—he always seemed to be smoking on camera or slaughtering a hog or getting his crew to film in the style of a cinematographer he admired. The result could be out of touch, or, as he once put it, “glib, green, and generally clueless.” But over the years, he became less charmed by doing whatever he wanted wherever he wanted and more interested in highlighting the reality that he was an American male making TV about food in some of the most impoverished and war-torn places in the world. In 2006 No Reservations was filming in Beirut when war broke out between Hezbollah and Israel. The episode became about Bourdain and his crew being taken by fixers to a hotel with a pool where they lounged and played cards as they watched the far side of the city get bombed before eventually being evacuated by Marines, and how arbitrary it all was. “I am lavishly rewarded for being myself,” he said in a 2010 interview.

The day he returned from Beirut, Bourdain and the woman who would become his second wife conceived their daughter. Bourdain was by then firmly out of debt, out of the kitchen, and in demand, where he remained, beloved as a moral authority and a malcontent, a savvy and crotchety man-about-the-world, until his death by suicide, on location for Parts Unknown in the storybook town of Kaysersberg, France, in 2018.

He is perhaps even more in demand now that he’s gone. A spate of books about him have been published since his death: Charles Leerhsen’s unauthorized biography Down and Out in Paradise; Bourdain, an oral biography edited by Bourdain’s former assistant Laurie Woolever; and In the Weeds, a memoir by Bourdain’s longtime director and producer Tom Vitale. Vitale’s book is the most revealing, focusing on what it was like to work with and for Bourdain—high standards and divo behavior, random acts of generosity, bitchy emails. On one occasion, Vitale writes, Bourdain strangled him while they were both drunk. Read alongside Bourdain’s own memoirs, the trio of recent books amount to something like a balanced portrait of an unsubtle and sometimes unstable man who loved hyperbole to death and had a talent for making everyone feel like they knew him best.

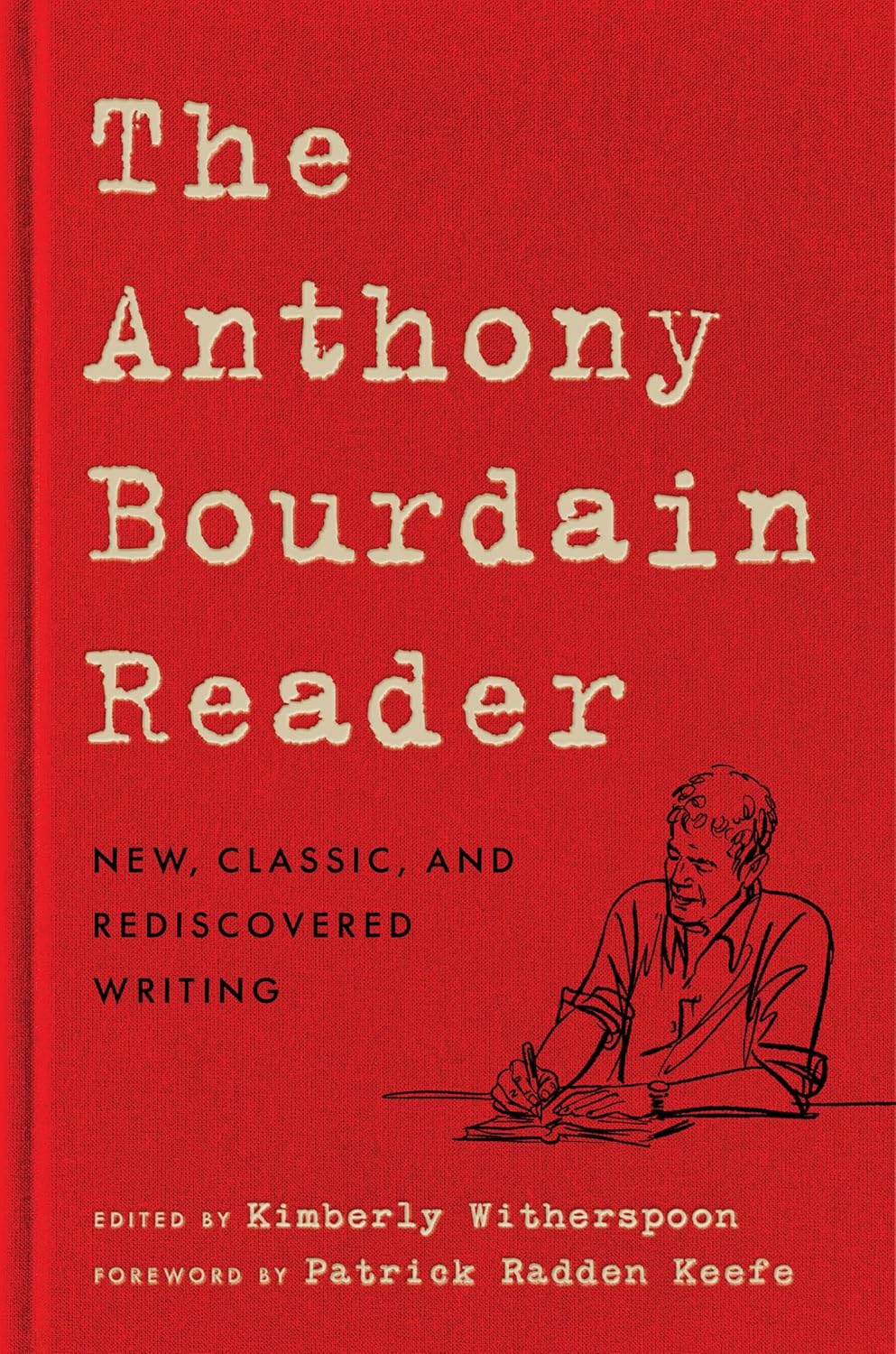

In comes The Anthony Bourdain Reader, an anthology edited by Bourdain’s agent Kimberly Witherspoon. Most of the book comprises essays and chapters from the books he wrote between shoots and a few random cookbook excerpts and pages from the graphic novels he coauthored. You get the sense that The Anthony Bourdain Reader was put together to honor an unfulfilled wish, and Witherspoon explicitly makes the case for seeing Bourdain “almost above everything else” as a serious writer. As Patrick Radden Keefe, who profiled Bourdain for The New Yorker in 2017, points out in his foreword: “He was a frustrated writer who spent the two decades before he finally hit it big working as a chef.” It was the frustrated writer who enrolled in and promptly had his ego wounded in Gordon Lish’s fiction workshop at Columbia in 1985. (When asked decades later, Lish remembered Bourdain but not his writing.) The Reader includes Bourdain’s early successes: autobiographical sketches originally published in the ’80s in influential literary magazines like Between C & D and ZAT. He was interested in heightened and debauched states of being and repeatedly wrote versions of the same story—young chef scores heroin on the Lower East Side—as if trying to perfect it. The Reader’s biggest get is probably the chapters from No New Messages, the crime novel Bourdain started in 2008 but never finished. The writing is self-assured and unfussy, Bourdain at his “serious writer” best. But there’s more to love in the trivial stuff. Wedged between the early fiction and the anthology’s dutiful selections of Bourdain’s polished work about eating poisonous fish and “Reasons You Don’t Want to Be on Television” is the true juvenilia: a bad poem called “Kitchen,” some diary entries, and unpublished, unedited fiction and scripts, mostly undated but some from as early as Bourdain’s teen years.

Cursed from birth with being twelve in 1968, Bourdain was miserable growing up because his parents loved him and nothing terrible had ever happened to him personally. From the confines of “the leafy green bedroom community of Leonia, New Jersey,” he longed for experience. “I’d wanted to become a junkie,” he claims in an essay about his misspent bourgeois youth, “since I was twelve years old.” When he was eighteen, he wrote a self-aware “true story” for his high school English class, included in the Reader, about a kid named Anthony Bourdain who embarks on a bender in search of what Hunter S. Thompson called “the Edge” in Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga. In Bourdain’s “A Strange and Twisted Adventure,” the journey to the Edge is almost too much for the narrator—“Christ, I’m only fifteen,” he says—but in the end young Anthony toes it with the help of a cokehead contortionist from Las Vegas named Panama Red. Teenage Bourdain was eager to romanticize grit and was pissed he had missed the ’60s. By the time he got to New York City, there was no way he was passing up the chance to join in on the heroin epidemic. Decades later, at a recovery meeting in New England filmed for his show, Bourdain told the group about how, the first time he shot up, in 1981, he felt proud: “I looked at myself in the mirror with a big grin.” In his biography, Leerhsen ventures, plausibly, “If you could have bought smack at Macy’s, [Bourdain] would never have gotten hooked. He was in it mostly for the atmospherics.”

This lust for experience was bound up with what Bourdain once called his “lust for print.” He was obsessed with becoming a writer, or at least with looking and acting like his idea of one. When he was a junior in high school, his father, who worked for Columbia Records, took him to an industry party. As Bourdain tells it, he wore dark glasses and introduced himself to women as a reporter for Rolling Stone, a child prodigy in the Cameron Crowe tradition. During his brief stint at Vassar in the ’70s, he took pains to appear dangerous, wearing nunchucks and carrying a samurai sword around campus, presumably because his literary tastes ran toward swagger and know-how and espionage and swashbuckling. (He read a lot of Tintin comics as a child.) In addition to Hunter S. Thompson, he loved William Burroughs and Graham Greene and A. J. Liebling and George Orwell (whose Down and Out in Paris and London inspired Kitchen Confidential). And he was obsessed with Heart of Darkness.

Among the earliest selections in the Reader are diary entries from a trip to France when he was eighteen. In loopy handwriting, he narrates his day:

Paris, with a cold. Jesus, why did I have to kiss the little bitch? My hair is gone. Cut. I feel as if I’m on a pilgrimage of sorts. My hair cropped, a new place, no one to talk to. But a nice hotel on the left bank. Near to a lot of cafes, good restaurants and Shakespeare and Co. bookstore. I’ll have to check it all out.

The drama! Here is a young man itching to be world-weary, to have agonies and ecstasies behind him instead of just a haircut and a sniffle. It’s like that video of a children’s choir paying tribute to Serge Gainsbourg, all of them dressed up like him, five o’clock shadow sponged onto their smooth faces and prop Gitanes and whiskeys in hand. The entry is, to me at least, touching for its obvious and effortful attempt at nonchalance—the fact that the affect is so easily seen through makes it almost more earnest than innocence. Here too are nascent qualities that would become Bourdain’s signature in the voice-over scripts he wrote for his shows: the cultivated sense of estrangement and loneliness in a new place, the cynicism and self-deprecation butting up against honest curiosity. There’s a consistency of voice across the Reader and Bourdain’s writing for his shows that makes you think he either never grew up, or that he has been grown-up since he was a teenager. Getting a travel show was, he often wrote, like receiving a golden ticket to live out all his “little-boy dreams of travel and adventure.”

Some of the juvenilia could have been written when he was fifty. We don’t know, for example, if Bourdain was the teenager he sounds like when he wrote the line, “MY LIFE IS A WORK OF ART GODDAMN IT!!,” which appears in a short, untitled, undated script about a young guy named Mike. This strange artifact includes dialogue like “Let’s rip this place up. Unconventional use of a conventional space. Very artistic,” followed by stage directions like “(hurls oriental ninja star at wall).” The tone is silly and self-serious, often the former because it’s the latter. We open on Mike and a friend in a room at a Holiday Inn, talking about their prospects. Mike is a writer and an optimist. “Someday people will look at us as the Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs of our day,” he tells Jeff, the musician, the realist, who seems to be awaiting an important phone call. But when self-doubt creeps into Mike’s monologue, his mother appears “from nowhere in strange blue light” to nag him about getting real and growing up, which of course is what prompts Mike’s all-caps line above. “Bullshit,” says Mother. Mike fires back in classic fashion with this:

But at least I want. I want to do something. That’s enough, isn’t it? It’s better than being content. It’s better than not wanting anything. I mean my various neuroses and dependencies are just the price I have to pay for wanting so much. I want to do, to go, to give. Really! Really!

And this:

Don’t interrupt me, Mom. I’m going to do it! I’m going to blow this country and live in Paris and drink wine and eat oysters! I’ll write great books. Hemingway on the Left Bank!

We’ve all heard this before. Bourdain’s one innovation is that his romantic young buck is never disillusioned. The script concludes with pure wish fulfillment: Mike is at a café in Paris when a girl approaches to ask where he disappeared to last night. “Sorry, sweetheart. Assignment on Venus came up and I had to split.” She wants to know if Mike, the dashing journalist and astronaut, might be free this evening? But then, suddenly,

Bank robbers run from door holding money and guns. Mike stands and takes off jacket and nonchalantly shoots them all with large gun from his shoulder holster.

MIKE: I hope you’ll excuse me for the interruption.

GIRL: Oh, that was all right. I rather enjoyed it, actually.

MIKE: Another glass of wine, maybe, and we’ll go back to my hotel.

GIRL: Gee, what a guy!

The war against cliché was never waged here. It’s absurd, a pastiche of every sad young literary man who ever lived, plus space travel and vigilante justice. As self-parody, if that’s what it is, this odd, three-page mash-up of scenes identifies Bourdain’s tics and tastes: his trigger-happy timing and histrionics, his love of gruffly effective guys and tortured artist types (and types in general), his indulgence of ennui and soul-searching, his gall. Still, something in me appreciates it against my better judgment, and insofar as it captures something true about Bourdain, it’s got integrity.

Though he was often seen as an iconoclast and a pillar of “authenticity”—a word he hated—what comes across most forcefully in his writing is an intense desire to be liked, to fit in, and to make it all look easy. He was an enthusiast, a try-hard, and a bit of a ham, continually in search of something bigger than himself to submit to, even conform to, whether it be the brigade hierarchy of a kitchen, the throes of addiction, or the customs of countries he previously knew only through books and movies. As many close to Bourdain have observed, the job that kept him traveling for two hundred days of the year for fifteen years straight could be seen as a vehicle for feeling at home and belonging, in however small or artificial a way, everywhere he went.

THE BEST ESSAY IN THE READER IS ABOUT CRIME FICTION, which Bourdain prized for its recognizable traditions and its “comfortably familiar phrase book, long ago codified and set down in Hollywood films, of the hard-core, professional bad man.” (He paid similar compliments to the “long and distinguished oral tradition” of back-of-house banter in Kitchen Confidential.) Bourdain tells us he’s indifferent to crimes of passion and that he doesn’t care about the sociopathic motives of teenage shooters. He wants to read about detached professionals and contract killings, about “crimes where you know from the get-go why they did it: because it was their job to do it.” He’s good on the wimpy line between real-life crime and crime fiction, the fact that probably everyone in the mob has seen all the Godfather movies. And he has a great run on the inherent comedy of wiseguys getting whacked:

Joe Pesci, thinking that today he’s gonna be a “made guy,” looks down at the floor, sees that the carpet has been rolled up, and has time only to say, “Oh shit!” before getting two behind his ear. Classic. Just like Oliver Hardy should know that a ladder will soon be bouncing off his face because it bounced off his face in the scene before, and in the scene before that—Pesci’s character should know that when a close personal friend invites you to a sit-down with the bosses, or says that you can have the front passenger seat (“That’s okay . . . you sit in front”), there’s every likelihood that a fatal head injury is imminent. There’s a historic inevitability to both comedy and organized crime, and the punch lines are often the same.

Predictability can be deeply satisfying. The epigraph to Bourdain’s first novel is a definition of mise en place: everything a cook might need is in its proper place. Working in TV, he developed a slightly looser fixation on mise-en-scène. Per a friend quoted in Leerhsen’s biography: “Tony had this thing where he liked to pretend he was living scenes out of movies. He was obsessed with movies. . . . He’d imagine he was the main actor, but at the same time he was, in his mind, a kind of set director who wanted to curate all the details of a scene—what everyone ate, the furniture, the clothing, the music they were listening to.” On his first visit to Russia in 2002, he cast himself and his St. Petersburg guide as spies, rendezvousing after exchanging code words (“The fish is red”; “Only on Wednesdays”). And his Miami episode had to have a sequence copped from the society-don’s birthday party scene in Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty. “I wanted to see the world—and I wanted the world to be just like the movies,” he wrote in A Cook’s Tour. The perverse apotheosis of all this was when Parts Unknown filmed a Congo episode largely because Bourdain wanted to re-create the river journey of Apocalypse Now, itself an adaptation of Heart of Darkness. The shoot was a disaster. Bourdain forced his director and cameraman to slaughter chickens on camera with a dull knife and then, for some reason, made coq au vin on the boat as the lights flickered on and off, attracting waves of poisonous moths. The meal was an hours-long ordeal during which Bourdain turned into a despot. Tom Vitale, remembering the snafu in his book, wondered if “Tony’s point” was “that we all have a Kurtz somewhere within us.”

Toward the end of his life, Bourdain developed a case of fame-induced agoraphobia. He talked about wanting to step back from the show, about how “in a perfect world” he wouldn’t be on-screen. “You would see what I see and I would write everything.” The fact that he had become the least interesting thing about the show was a mark of its success; ideally, he would be more facilitator than front man. He wanted as many people as possible to see and understand what he had of the world, partly, I imagine, because having back-to-back once-in-a-lifetime experiences gets isolating after a while. More world-weary than he had bargained for after getting everything he had once wanted, now all he wanted was what his invariably more sedentary viewers had. He talked to colleagues about quitting the show to spend time staying put with his daughter. His producers encouraged him to leave, but he never did.

After years of literally dining out on his reputation, Bourdain’s contradictions had become his calling card. To his fans, he was a saint because he was a sinner; people wanted to be close to him because he was so prickly; he was honest to a fault and at the same time a willing poser; he lived an exceedingly full life but was always joking about being one bad cheeseburger away from ending it all. Over the years, he talked about killing himself in his lonely hotel room countless times on-screen. He always made it sound like a joke and maybe it always was, but after his death, there was such an abundance of material in plain sight that some close to him spoke of a kind of supercharged survivor’s guilt, a feeling that they should have seen it coming.

The fullest and most simpatico expression of Bourdain’s sensibility in the Reader is a previously unpublished story called “Mauser.” It can be read as a parable about being contrary. We follow a misanthropic narrator to a swanky party where he has vaguely planned to commit performance art by killing the attendees, former college classmates of his. The narrator, a petty criminal who “had been watching television for around four months when the invitation arrived,” takes great care to primp for the big day. He buys a new suit, gets a haircut, and lovingly attends to his gun, the eponymous Mauser. When he arrives, the insufferable hosts Mutely Prince and Kathleen Bradford are unexpectedly polite and pleased to see him. This won’t do. So when Kathleen offers him a glass of champagne, he bites it and spits glass onto the cheese board. “Kathleen, to my surprise, looked delighted at my impromptu gesture, and giggling, she took a bite out of her glass.” The same thing keeps happening: he sets a man in a polyester suit on fire, but the man is unharmed and excuses himself to change his clothes while the other guests titter with excitement; when he slashes a Matisse of Mutely’s, his gracious host responds by throwing a potted plant at the painting; he jettisons the TV from the tenth-floor apartment’s balcony, which the guests take “as some sort of cue” to go berserk, start a food fight, urinate on each other. At every turn, the thing the narrator thinks is going to happen doesn’t. He is not having the effect he intended. Rendered impotent by the partygoers’ appetite for mutually approved destruction, he is the only guest left with any decorum. The only subversive thing to do is to leave his weapon on the floor. Will the guests finish each other off? Bourdain would have done better to let the ending be ambiguous, but you get the sense that he was too pleased with himself to stop.

Lizzy Harding is a writer in New York and Bookforum’s former associate editor.