David O’Neill

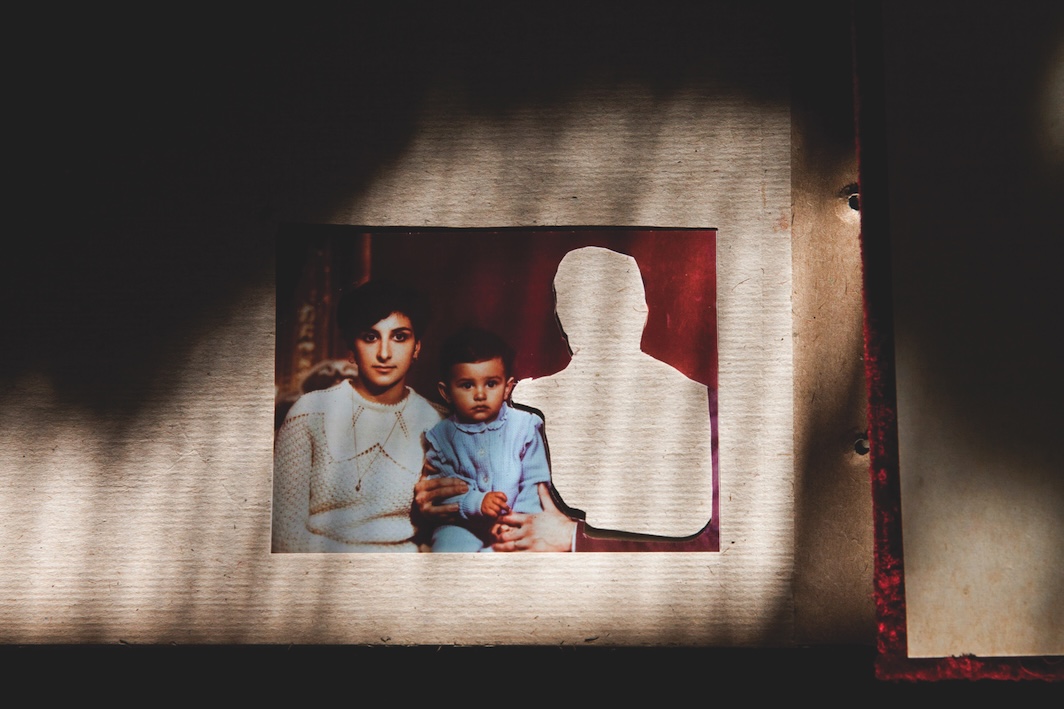

IN THE EARLY 2010S, photographer Diana Markosian traveled to Armenia to meet her father after a separation of more than fifteen years. They hadn’t seen one another since Diana’s mother, Svetlana, took her and her brother from Russia to California when she was seven. “I am Diana, your daughter,” she said. He replied, “Why did […]

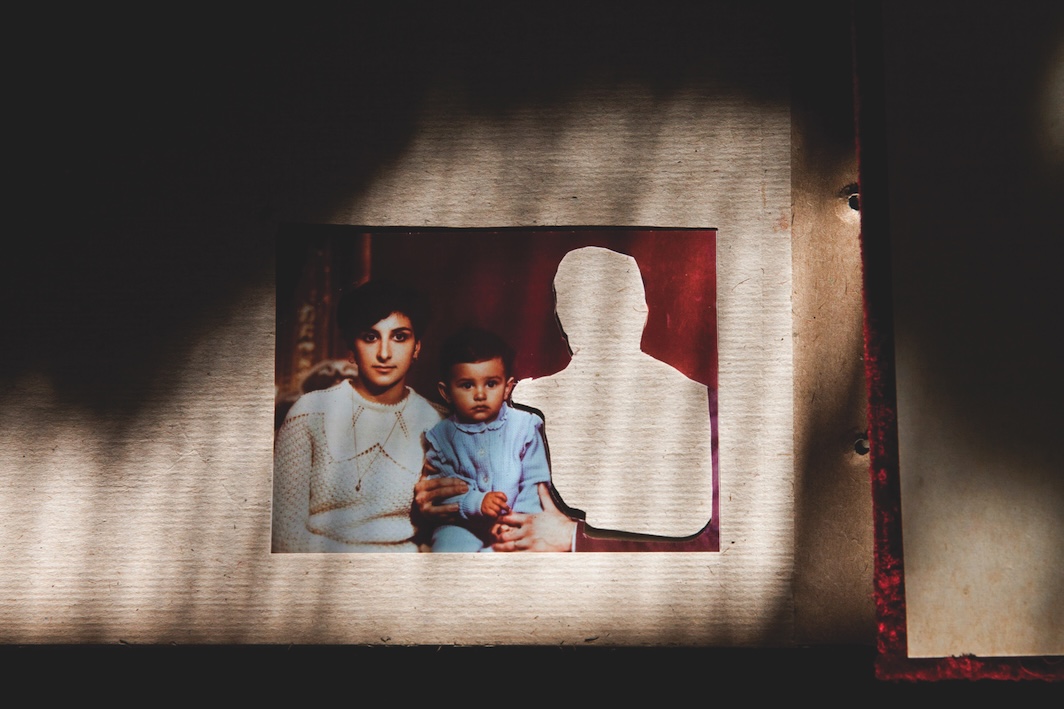

Ming Smith, Greyhound Bus, Pittsburgh, 1991, gelatin silver print. From the series “August Moon for August Wilson,” 1991. © Ming Smith, Courtesy the artist and Aperture SOON AFTER ARRIVING in New York in 1973, Ming Smith sold two pictures to the Museum of Modern Art (New York), becoming the first Black woman to be granted […]

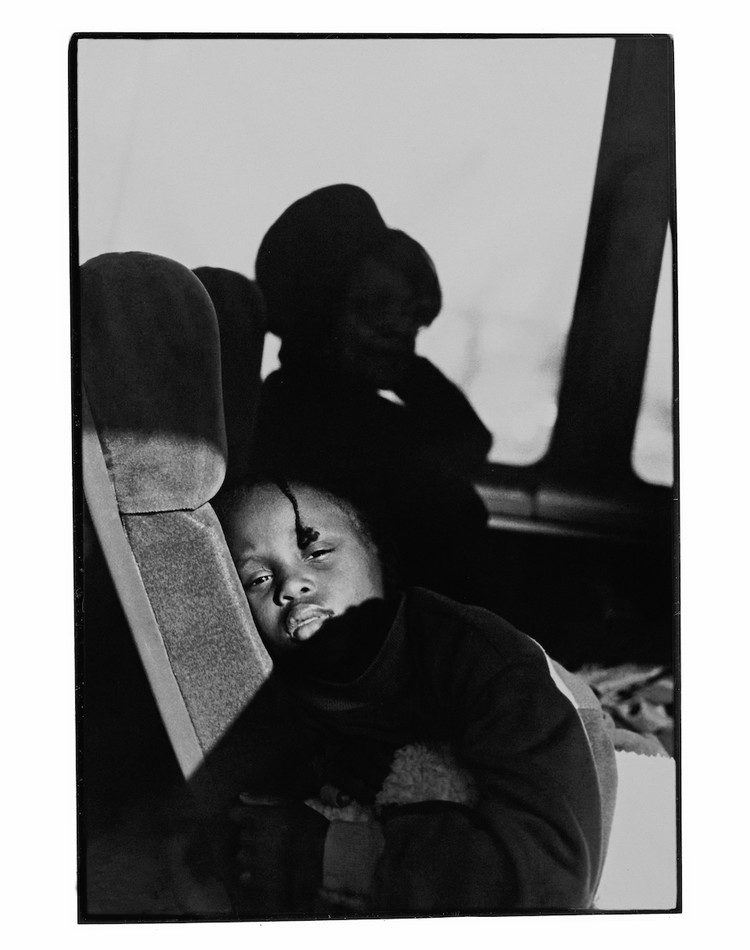

JACQUES HENRI LARTIGUE (1894–1986), an artist whose work seems to come from another world but in reality comes from the past century, captured that era’s experience of speediness, of beauty, of carelessness, of fun. Born in fin-de-siècle France, Lartigue started shooting film as a child. Though he thought of himself as a painter first, Lartigue became famous for photographing auto races, early aviation, beachside horseplay, and society women on the Bois de Boulogne. He pioneered techniques for capturing heart-stopping proto-parkour, like a quick dandy jumping over some lazy chairs, or, in My Cousin, Bichonnade, 40 rue Cortambert, Paris, ca. 1905,

DAVID O’NEILL: Your new volume of photos and writing, This Brilliant Darkness: A Book of Strangers (Norton, $25), is bookended by two medical emergencies. It begins with your father having a heart attack—you started taking these pictures shortly afterward—and, two years later, as you were finishing up the project, you had a heart attack, too. You write about this in the first pages. I can’t help but see what follows as being about mortality, solitude, and a reckoning with “darkness.” But the book is not morbid—it’s about that darkness, but also connection, empathy, and the vividness of any particular moment. THE LATE SARAH CHARLESWORTH made powerful and desirable work about power and desire. Like her Pictures Generation allies, she rephotographed and repurposed mass-media images—of Buddha statues, figures from Renaissance paintings, hip-hop stars—taking advantage of the dense fields of pictorial meaning available everywhere. Charlesworth was neatly analytic in her approach, creating an oeuvre that can seem like an essay collection. This isn’t to say her pictures are dry. Beneath the perfect surfaces lies a wild inquiry into the messiest of questions—above all, those about photos’ potent contradictions: how they are deceptive and honest, universal and personal, alienating and beckoning. IN 2010, Richard Misrach returned to photograph the stretch of Louisiana known as Cancer Alley, a 150-mile section of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, which he had also explored in 1998. The area is home to petrochemical plants that have polluted the river and spoiled the environment for years. But Misrach’s Petrochemical America is more than a disheartening photographic essay on the evils of Dow Chemical. Along with ashy skies and cloudy rivers, we see plantation tour guides and the restored slave cabins they show visitors, ramshackle churches, tankers and fishing ships on the Mississippi, rickety EARLY IN HITCHCOCK’S VERTIGO, we follow the hapless former detective Scottie as he trails his mark, Madeleine. He’s driven, in part, by a half-baked tale of reincarnation: She’s a dead ringer for the deceased Carlotta Valdes. The tension and suspense build as Hitch uses every trick in the cat-and-mouse book of filmmaking. The sequence reaches its discordant crescendo, though, when Madeleine enters the California Palace of the Legion of Honor and contemplates a portrait of the mysterious Carlotta, which . . . really does look a lot like her. Beyond the passing resemblance, the portrait possesses a strange power as A born rambler, Justine Kurland has been traveling across America with a camera for the past decade. In 2004, when her son, Casper, was born, she took him along for the ride. Their camping van soon became crammed with toy trains; Casper’s enthusiasm for locomotives was infectious, and Kurland’s work began to explore real railways, as well as the train hoppers and hobos she met along the way. Like any parent, she also frequently aimed her camera at her child, as he toddled through the blighted and bountiful landscape of America’s backwoods and slept in a cozy bed built into New Yorkers encounter the peculiar, comic-sounding word knickerbocker all over the city: on street signs and at subway stops, in the names of condominiums, restaurants, and bars, and—shortened to the catchier Knicks—on basketball jerseys. When consummate man-about-town George Plimpton died in 2003, the New York Observer called him “the last Knickerbocker.” But what is a knickerbocker? Is being called one praise or a curse? According to historian Elizabeth L. Bradley’s new study, the term has been “used alternately with reverence or disdain” over its two-hundred-year history, quickly slipping its original meaning to become a “link between a strange, sometimes unholy Emily Dickinson’s legendary silence has produced a discordant chorus of speculation and mythmaking. As Alfred Habegger, her best biographer, has written, Dickinson’s “reclusiveness, originality of mind, and unwillingness to print her work [have] left just the sort of informational gaps that legend thrives on.” Readers and scholars alike have endlessly revised this legend, struck by the conviction that Dickinson speaks directly to them. Adding to the noise is the decades-long effort by the poet’s heirs to control her legacy, engendering incomplete and distorted editions of her work. This tendency is exemplified by the photo of Dickinson featuring fluffy hair and