IN A RECENT PIECE FOR GAWKER, “Gary Indiana Hates in Order to Love,” Paul McAdory looked at how the writer makes affective intensities cooperate. “Indiana’s greatness,” McAdory wrote, “rests partly on his ability to fling aside the sheer curtains partitioning love from hate and extract a superior pleasure from their mixture.” It may be bad form to quote a parallel review of the book I’m looking at—Fire Season, a collection of essays stretching back to 1991—or maybe it’s just confusing to do so without going into attack mode. Sorry, odiophiliacs! I want to simply agree with McAdory’s essay and say that consensus is interesting. We need the particular epoxy of hate and love that binds Indiana’s best work. He is very much not a twitterhammer who chases dunks for space bucks. Indiana’s hatreds are healthy and intertwined and various, few of them shallow. In 2014, Indiana described William Burroughs’s stories as “torrents of Swiftian misanthropy in vignettes of atomic doom,” which describes his own work, roughly. What it pins down, with less roughness, is the sense of stakes in Indiana’s rainbow of rejection. Was there ever a vote on what snark actually is? Whatever it is, that is not what Indiana sells. Many of his most barbed darts are delivered with affection, and considerable attention to detail. In his folding rifle of a campaign-trail report from 1992, “Northern Exposure,” he describes Bill Clinton’s face as “a visage of pure incipience: soon-to-be-jowly and exophthalmic, a fraction past really sexy, but warmingly cocky, clear-eyed, with an honorary, twinkling pinch of humility.” There is much to love there, but it’s the “honorary” for me—the idea that Clinton has bestowed the humility on himself, thereby voiding its authenticity. But Indiana grants him “warmingly cocky,” very different from warm or cocky or cockily warm. No—the needle moves slowly over the flesh until it hits a vein.

In an April Zoom interview with Christian Lorentzen, Indiana said he preferred European novelists while growing up because of his sense of “foreignness” in relation to the various American narratives being sold at home (originally New Hampshire). He added that his life as a critic began in part because someone needed him to do the job—at first, the Village Voice. His need to write was not tied specifically to any particular mode, beyond paying the rent. It is the sense of being engaged in a wider moral task that feels more European than his disdain—or his taste for arm-sweeping an improbability off the table. Like so: “I have never discovered a single worthwhile item in the comment threads attached to online stories,” Indiana wrote in a 2018 preface to Vile Days, his collection of Village Voice art columns. These pronouncements are more careful than they first appear. Only a writer spoiling for, well, a comments-section fight would imagine that Indiana had read all the existing comment threads and held him to that pseudoscientific baseline.

He shares the quasi-European stance with another quasi-European, Susan Sontag, an erstwhile friend he has often been compared to. It’s not a bad pairing to keep in mind, in that neither have any respect for punditry or specialization, two distinctly American ways of existing as a writer. Critic work comes easier than fiction or drama because there is always a proximate need, and the requirements are nonexistent. An editor has to plug a hole, and Indiana was able to fill ’em all while he was creating plays and novels and video works and radiating out into the world from a home base on East 11th Street, a fact he is resistant to overemphasize, given his “strong distaste for the Eighties nostalgia” that tends to seek out East Villagers and amplify both their movements and their importance.

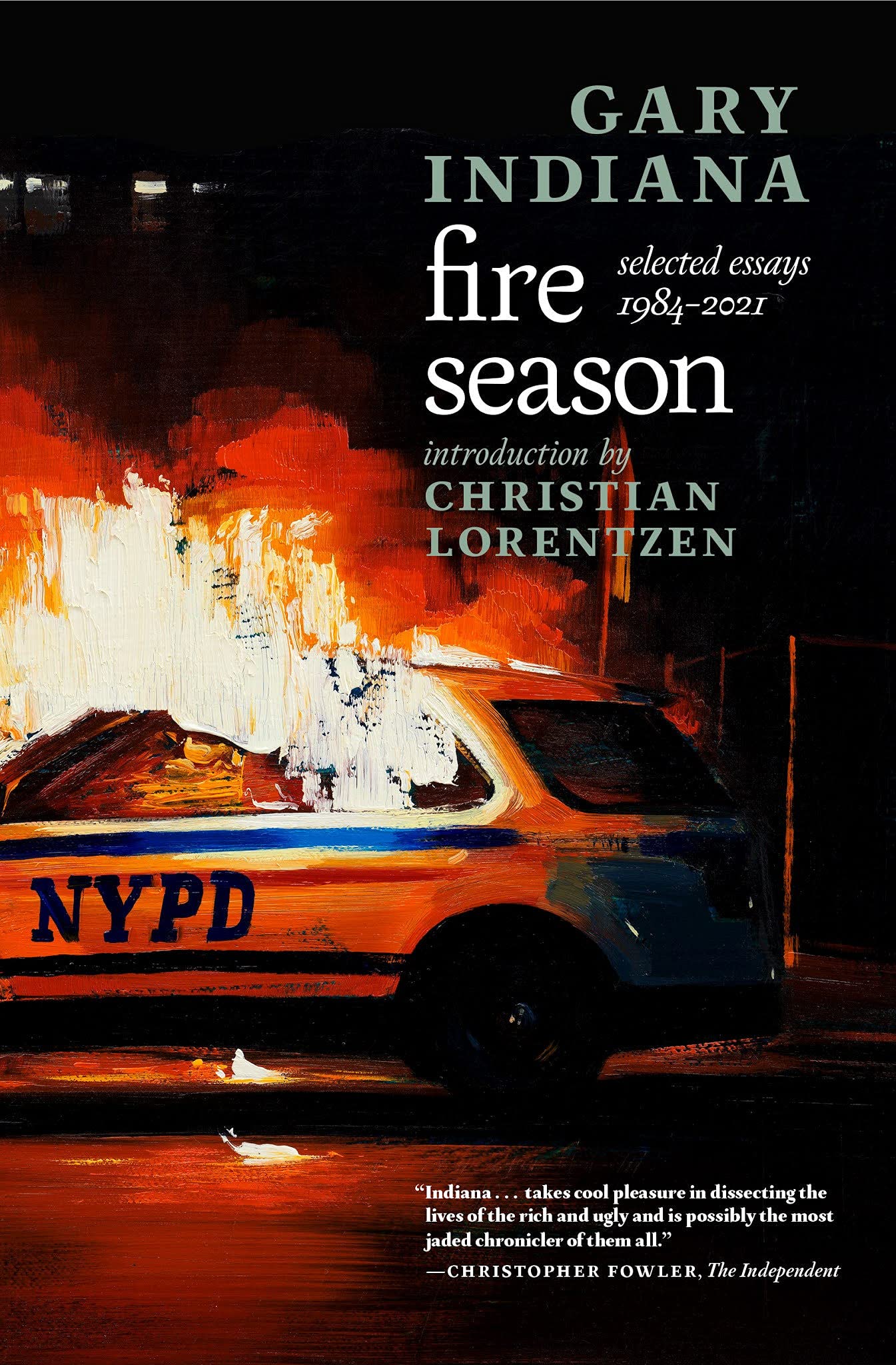

The ’80s art essays from the Voice are (in part) in Vile Days, and Fire Season only addresses visual art intermittently. Indiana has a tetchy relationship to those art pieces, which he describes in his 2015 memoir I Can Give You Anything but Love as “a bunch of yellowing newspaper columns I never republished and haven’t cared about for a second since writing them a quarter century ago.” The variety of pieces in Fire Season better suits Indiana’s remit. We begin with a 2014 piece on fierce Putin critic Anna Politkovskaya, which also highlights some of the limits to the Indiana approach. If you don’t know what the Nord-Ost hostage crisis was or how Politkovskaya died, Indiana does not spell it out for you. His admiration for this writer’s bravery is only one impetus for the piece; when he writes “we expect journalists to be magically immune to real danger, in part because they are, technically, ‘civilians,’” he is setting up his larger point: “It is, in reality, all the same war, everywhere and endless, subsiding in one place as it flares in another.” When he quotes Politkovskaya speaking about her own work, to close the piece, it seems clear his own answer is no: “The important question is, what change has our article brought? Has something changed for the better in our society?” That conclusion is only more obvious eight years later. The longest piece, “LA Plays Itself,” documents the 1993 Rodney King trial—the second, federal proceeding—with an icy thoroughness, underplaying the many blossoms of horror afforded by the cops and their vortical excuses.

Indiana cares about sentences and he cares about his friends. “A Coney Island of the Viscera” documents his friendship with Louise Bourgeois and her stash of psychoanalytic writings. “Today’s MacArthur genius is tomorrow’s Edna Ferber,” Indiana notes, in defense of the Bourgeois fragments not being “intended as literary works.” The different rhythms and tonalities Indiana uses in this one short piece do such a good job of mirroring the mind’s attitude toward itself, and how it stages information. He opens with, “When I met her, in the mid-1980s, it was by way of a mash note she sent in the mail to the paper I wrote for, not so much thanking me for a review but offering something better than thanks: a terse, oddly touching missive indicating that I’d fathomed her current show very well.” Self-congratulatory, for sure, while also revealing the quickness of their intimacy. Perhaps sensing his own peacockery, he instantly wets the feathers: “We were both intellectually combative, anxiety-ridden, insecure, depressive, and wretchedly insomniac, and we both sported egos prone to inflate like dirigibles, then shrink to pea-size within the span of a sneeze.” As for her hoarding, he keeps it quick: “She never threw anything out.” Here, and elsewhere, Indiana is a staunch defender of the formally unusual, the writing that resists easy flogging. He takes Bourgeois’s writings as seriously as he takes her art, calling them “close mimicries of consciousness” which “necessarily resist cohesion.” He reads her stubborn little poems with a grave affection. “Some pages simply list associations around an isolated fixé,” Indiana writes, “like a broth reduction.”

“Northern Exposure,” originally for the Voice, is a good example of his care and carefulness combined. (Along with the King piece, this report makes a strong case for Indiana being hired right now, today, as a feature writer unburdened by a word count ceiling.) Watching Jerry Brown speak, he is annoyed, possibly because of “the memory of a large crow I once saw bisected by one of Jerry’s power-generating windmills outside San Luis Obispo.” But it’s not that—it’s the small child playing with a Nintendo Game Boy next to him. Those technological details time-stamp this piece beautifully, but it’s that need to both report and observe that characterizes Indiana’s best work. (He told Lorentzen he moved away from criticism initially because he wanted to do more reported work.) First referencing the “tedium of the campaign trail,” Indiana writes that he was “moved to tears one morning by a CNN report on unemployed factory workers in West Virginia.” OK—not a monster, not an elite perched in the opinionarium. He brings his cousin Kathy some lunch his mother has prepared (a way to immediately make the hometown connections concrete) and mentions that Kathy has “just opened a tax accounting service in town, having left her job at a law firm that lost its major corporate client.” We are getting the jobs report in a short burst of bullets. Kathy, “one of the least neurotic, most industrious people” Indiana knows, reminds him how much they all wanted to escape the factory life. After noting his “class hatred” of “New Hampshire yuppies” who worry about tree conservation, he clarifies: “I will never be rich enough to spend all day worrying about acid rain and printing brochures about it on recycled paper.”

Indiana has little common cause with the take-meisters because his stories are quite wide in emotional tone, rooted both in his experience and a political conscience. As heartbreaking as the issues of 1992 could be, they were all episodes in another endless conflict: class war. The recent quote that has stuck with me is a comment he made to Tobi Haslett about Ulrike Meinhof in his “Art of Fiction” interview for the Paris Review: “Having a million opinions about everything comes cheap and easy, whereas actually doing something can cost you quite a lot.”

It is the inescapable density of life that propels Indiana, a sense that experience deserves to be written about, but also that writing must not dissolve into the weak gas of opinion. In a bit on Masha Gessen’s book on the Tsarnaev brothers, Indiana drops a comment on the state of executions that takes the physical into account as much it traces the political. “In recent Ohio, Arizona, and Oklahoma executions,” Indiana writes, “a European export embargo on lethal injection drugs has prompted mix ’n’ match improvisations with untested pharmaceuticals, with results Josef Mengele would consider plagiarism.” Indiana’s work is sensitive to the endlessness of the feeling within the endlessness of the pain. Things actually happen—life is not a wacky accretion of characters who conveniently embody that week’s intellectual whims. Executions hurt like hell and money changes everything. For someone who got so used to pillorying the moneyed in the art world, it is telling that he begins Andy Warhol and the Can that Sold the World (2010) by noticing the artist’s “work’s almost surreal financial appreciation.” That seems a minor line but it is not. To remember, again and again, the real that defines the surreal is an almost unbearable burden, and also the reason to write, for Indiana.

Maddeningly, it is not indicated in Fire Season where the essays were first published, so I can’t tell you what “Romanian Notes” is or why it exists. (It seems to be Indiana roaming around Bucharest and taking notes.) Amid a horny foray in a carpet shop, Indiana is thinking about war and surveillance and the American love of a good coup. I enjoy his descriptions of the merchant Ahmet, who “had a Wagnerian opera’s worth of rug chat stored in an otherwise fallow brain,” but I am reassured by Indiana the preacher, calling the demon sprawl of bureaucracies “glue traps for federal revenue.” I am thinking of the DHS’s federal police thrashing pro-abortion protesters in LA in early May, begging the question of what exactly homeland security was being threatened. As always—the money. “The overriding imperative of any bureaucracy funded by the state is its own self-perpetuation,” Indiana writes from Bucharest. Specifically, “an anti-terrorism agency will breed its own terrorists, attracting weak-minded, potentially volatile people into bogus conspiracy cells.” As soon as I find myself thinking about people being kettled and clubbed for caring about the lives of women, I find myself thinking about how Indiana would report it. Who better to write about the functionaries who see bodies on the street as an opportunity to divert billions for armored vehicles and technical athleisure?

That sense of events always representing a political commingling is at the heart of his 1991 piece on Oliver Stone’s JFK. “Like so much of modern life unanticipated by the Constitution, the saturation booking of two thousand theaters for a single director’s version of Gandhi or Jesus Christ or the shooting of JFK is something we just have to live with, along with the easy purchase of Uzis and AK-47s.” So many editors would beg Indiana to remove that last phrase. You can imagine the Google Doc note: “Totally understand the mood, as it’s an assassination pic, but it seems redundant? And JFK wasn’t shot with either of these guns. Perhaps cut for length?” But those easy purchases have trebled since 1991, and we now live in a world where presidential assassinations feel somehow lackluster. Three presidents killed simultaneously with robot shrimp? That would be a movie. Or a news item. Hopefully Indiana will write that column.

One of my favorite pieces is on Renata Adler’s novels, Speedboat and Pitch Dark, and which, it so happens, appeared in these pages. Unpredictable books written by a predictably lauded writer is exactly the kind of thing to throw Indiana at, and he spots the miraculous twist of these books in their use of first person. He also, it seems, spots himself. The stories in Speedboat “convey a class solidarity that has less to do with money than with education and an interest in politics and culture, a fair degree of social polish (often observed in the breach), and ethical scruples that preclude certain forms of success and facilitate others.” Indiana notes that Jen Fain, the writer-narrator of Speedboat, a novel “unfettered by plot,” is a version “of Renata Adler by Renata Adler,” which he defends as “barely remarkable.” (He seems to feel the need to protect a fellow mosaicist.) Indiana snaps at the “thought debris” of the internet, where words like “experimental” are used to describe Adler’s novels not as a way of taking “delight in all literary forms” but as “filtering screens for the literary market, which is currently dominated by aesthetic conservatism of a depressingly conformist ilk.” That Indiana would not find fellows on the internet is not remarkable, either. I like Indiana’s kicker here, that Adler’s novels are valuable because they tell us “what it’s like to be living now, during this span of time, in our particular country and our particular world.” He likes writers to kick against bourgeois pruderies and their accommodationist love of genre, that which can be most easily sold. (The exurban proximity in the early twenty-first century of McMansions and Barnes & Noble outlets springs to mind.) The key line is one that Indiana quotes, a piece of one of Jen Fain’s monologues: “I don’t think much of writers in whom nothing is at risk.” Indiana’s reputation as mean is such an odd categorization for someone who is so capable of feeling the struggles of his subjects, to see their risk as his own.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a writer and musician living in the East Village. He recently completed a memoir.